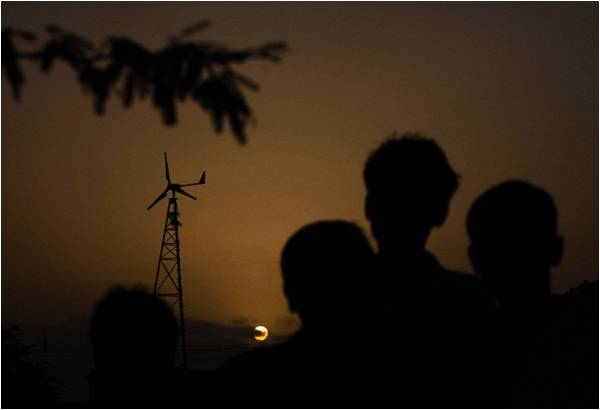

The recent move of the Cabinet Committee on Energy to impose a ban on setting up any new wind or solar energy projects in the country is counter-productive.

There is little explanation as to why renewable energy has suddenly gone out of favor. For those of us who follow the global energy market, it is shocking to realize that there are still governments that feel the need to debate the stature of renewables as the energy of the future. Equally, that they do not necessarily accept that those cashing in on the early mover’s advantage in the renewables arena will be far better off than those who keep waiting for others to show them the way.

Ostensibly, the Pakistan government’s rationale for the ban on wind/solar projects is the higher electricity cost. LNG gas (RLNG) seems to be the new flavor of the month which the government argues is a far cheaper alternative. Let us reconsider this rather simplistic assessment. I’ll focus on solar photovoltaic (PV) here.

Keeping in view the tremendous growth of Solar PV, the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA) issued the first tariff for grid connected solar PV plants in January 2014 and revised it downwards in January 2015, in line with the drop in price of solar PV. Today, the cost of electricity generated through solar stands at around Rs 14/unit (kilowatt-hour or “kWh”) and this cost is expected to drop further due to falling prices (the capital cost of solar projects is declining constantly).

On RLNG, Pakistan is essentially buying LNG on the spot market (daily price in layman terms) and is therefore exposed to the swings in global LNG pricing. This is a fairly volatile market: LNG FOB price rose to $19/Million British Thermal Units (MMBTU) in the first quarter of 2014 and current import price for Japan, one of the largest importers in the world, stands at around $14.3/MMBTU. In addition, the government has a “take-or-pay” contract with the sponsors of the Floating Storage and Regasification Unit (FSRU) at Karachi. Such a contract necessitates that Pakistan pay a minimum of approximately $0.25 million/day even if no LNG is processed from the terminal. This implies that the price risk associated with delays in gas shipments, unavailability of transport tankers, and at least the theoretical possibility of the Qatari Government cancelling the LNG contract at a 90 day notice is transferred to the LNG buyers in Pakistan.

As I write, the FSRU is being used as a transport vessel due to the unavailability of a transport tanker ship and Islamabad is paying the daily take-or-pay tariff to the FSRU sponsors for the travel time between Qatar and Pakistan. Only this transport cost for the 5-6 day trip comes to $1.25 to $1.50 million.

The Rupee’s devaluation adds to the cost further. The current tariff for RLNG-based power plants has been ascertained at about Rs 9.5/kWh and assumes a $12 per MMBTU price of LNG (which itself is expected to rise). Since all payments for imported fuel are in dollar denominations, any devaluation of the Rupee adds to the cost exponentially. To put numbers to this, if one recalculates the RLNG-based tariff using average devaluation of the Rupee over the past 7 years (approximately 7.5% per year), you get to Rs 17.6/kWh. The figure rises to Rs 20.15 per kWh if one uses a more realistic $14 per MMBTU import price figure for LNG.

And this is not all: we still have to build pipelines for the RLNG to be supplied to Punjab where a number of new development projects are envisioned. The RLNG tariff calculations do not reflect this cost.

To be clear, renewables are not about to substitute any of the traditional energy sources. Renewable energy projects cannot be used as base load generators nor can they totally replace fossil fuel power stations. But this ought not be the reason to make a radical shift towards ignoring them in outright defiance of the global trend. We lack expertise in the renewable sector that could match those in the traditional energy sector. This is leading the officialdom to consider renewables as too risky a bet and forcing the bureaucrats to do what they do best: continue operating in more familiar territory. In this case however, it is detrimental to do so as it is coming at the cost of more opportune choices.

The writer is an energy consultant with over two decades of experience in international energy markets and investments

There is little explanation as to why renewable energy has suddenly gone out of favor. For those of us who follow the global energy market, it is shocking to realize that there are still governments that feel the need to debate the stature of renewables as the energy of the future. Equally, that they do not necessarily accept that those cashing in on the early mover’s advantage in the renewables arena will be far better off than those who keep waiting for others to show them the way.

Ostensibly, the Pakistan government’s rationale for the ban on wind/solar projects is the higher electricity cost. LNG gas (RLNG) seems to be the new flavor of the month which the government argues is a far cheaper alternative. Let us reconsider this rather simplistic assessment. I’ll focus on solar photovoltaic (PV) here.

Keeping in view the tremendous growth of Solar PV, the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA) issued the first tariff for grid connected solar PV plants in January 2014 and revised it downwards in January 2015, in line with the drop in price of solar PV. Today, the cost of electricity generated through solar stands at around Rs 14/unit (kilowatt-hour or “kWh”) and this cost is expected to drop further due to falling prices (the capital cost of solar projects is declining constantly).

On RLNG, Pakistan is essentially buying LNG on the spot market (daily price in layman terms) and is therefore exposed to the swings in global LNG pricing. This is a fairly volatile market: LNG FOB price rose to $19/Million British Thermal Units (MMBTU) in the first quarter of 2014 and current import price for Japan, one of the largest importers in the world, stands at around $14.3/MMBTU. In addition, the government has a “take-or-pay” contract with the sponsors of the Floating Storage and Regasification Unit (FSRU) at Karachi. Such a contract necessitates that Pakistan pay a minimum of approximately $0.25 million/day even if no LNG is processed from the terminal. This implies that the price risk associated with delays in gas shipments, unavailability of transport tankers, and at least the theoretical possibility of the Qatari Government cancelling the LNG contract at a 90 day notice is transferred to the LNG buyers in Pakistan.

As I write, the FSRU is being used as a transport vessel due to the unavailability of a transport tanker ship and Islamabad is paying the daily take-or-pay tariff to the FSRU sponsors for the travel time between Qatar and Pakistan. Only this transport cost for the 5-6 day trip comes to $1.25 to $1.50 million.

The Rupee’s devaluation adds to the cost further. The current tariff for RLNG-based power plants has been ascertained at about Rs 9.5/kWh and assumes a $12 per MMBTU price of LNG (which itself is expected to rise). Since all payments for imported fuel are in dollar denominations, any devaluation of the Rupee adds to the cost exponentially. To put numbers to this, if one recalculates the RLNG-based tariff using average devaluation of the Rupee over the past 7 years (approximately 7.5% per year), you get to Rs 17.6/kWh. The figure rises to Rs 20.15 per kWh if one uses a more realistic $14 per MMBTU import price figure for LNG.

And this is not all: we still have to build pipelines for the RLNG to be supplied to Punjab where a number of new development projects are envisioned. The RLNG tariff calculations do not reflect this cost.

To be clear, renewables are not about to substitute any of the traditional energy sources. Renewable energy projects cannot be used as base load generators nor can they totally replace fossil fuel power stations. But this ought not be the reason to make a radical shift towards ignoring them in outright defiance of the global trend. We lack expertise in the renewable sector that could match those in the traditional energy sector. This is leading the officialdom to consider renewables as too risky a bet and forcing the bureaucrats to do what they do best: continue operating in more familiar territory. In this case however, it is detrimental to do so as it is coming at the cost of more opportune choices.

The writer is an energy consultant with over two decades of experience in international energy markets and investments