In a world of steel-eyed death and men who are fighting to be warm,

“Come in,” she said,

“I’ll give you shelter from the storm”

– Bob Dylan

Most of the musicians I ever knew at school were a lugubrious set, inclined to maunder about in flocks, write appalling poetry, and wear far too much black. Naturally, this made them infinitely interesting, although I cannot remember ever seeing any of them actually play anything remotely resembling an instrument. It may have been enough merely to play the part. This was still the early 1990s and “underground” music, like a distant but interesting relative, hadn’t quite made it to the provinces. To my chagrin, it wasn’t until much later (and several years after everybody else) that I discovered that Lahore-based bands such as The Trip and Co-Ven had produced not only stunning covers of Pink Floyd, but also their own music, reworking folk melodies into rock. And the only “proper” musician of my own school friends had gone on to form Bumbu Sauce and produced a characteristically irreverent canon of Punjabi-and-English punk rock.

This sketchy background, I acknowledge ruefully, does not make for a seasoned critique of indie music in Pakistan some 15 years after I first stumbled onto what is wryly known as “the scene”. It also meant stealing onto the grounds of the Storm in a Teacup festival last Sunday, feeling not unlike a gently aging rock groupie. But this year’s edition rides on more than the sheer charge of youth. There are performers here who take their music seriously enough to consider it a viable career – but for the need to make some sort of living until they succeed. And there are as many, if not more, for whom music is something they create because they enjoy it. There is, muses Masterjee Bumbu, an “almost physical need for creative release.” In his case, he acknowledges, this is accompanied by “the inevitable desire for global domination”, but most of the performers I can see at the festival are having far too good a time to worry about such trifles.

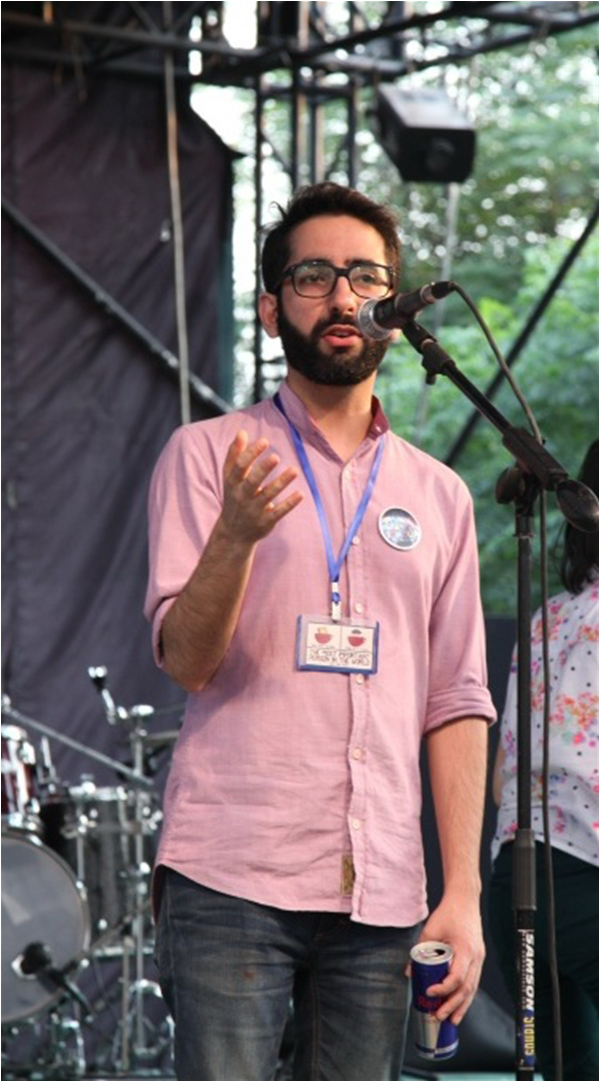

Here, at Peeru’s Café in Lahore, is a line-up of acts whose names trip satisfyingly off one’s tongue: Red Blood Cat, Basheer and the Pied Pipers, Keeray Makoray, Shorbanoor, Slowspin, Nawksh, Rudoh, and Omar Farooq. The gifted Jamal Rahman, who curates and produces the festival, says that his choice of artistes draws largely on “stuff that excites me” so long as they meet his clearly stringent standards of musicianship. His criterion is that the line-up should consist of bands that are doing “something fresh, something new”, a large part of which comprises experimental electronic music, but also spans innovative songwriting and progressive jazz. There is a wide enough range of music being played – and of musical tastes – he says, that the mix is inevitably eclectic. His production company, True Brew Records, was inaugurated in 2010 as a platform that sought to provide a recording space and high-quality production facilities to artistes wanting to explore alternatives to mainstream music producers.

The point of music is performance

But for him, the point of music is performance, not merely production or distribution. He describes it as wanting to “build a scene” – a sustained conversation of sorts that has more to do with performance and where production and distribution are there to support the former rather than the other way around. The festival is certainly the next step in this direction, he says, but the idea is to enable smaller, less sporadic concerts that allow musicians and artistes to engage with each other purely on the basis of who likes what and without the layers of “technical” makeup associated with more commercial gigs. The broad canvas of indie music isn’t, then, about showmanship or theatre. It is far more honest, says Jamal: “No one is pretending to be anybody else. No one is out to impress. They play what they want to play” and it is up to their audience to like it or otherwise.

Taste, not endorsements, should drive performances and empower musicians

Jamal underscores how important it is to understand what goes into putting on a festival like this. The existing – and entirely unsatisfactory, in his view – model is for indie bands to find they must rely on corporate sponsors to enable their performances. Most such sponsors choose not to charge for such events, instead distributing “free” passes and gaining the advertisement space they want. What needs to happen instead, explains Jamal, is for the audience to be prepared to pay to see the bands they like. This allows taste, and not endorsements, to drive performances and empower musicians, producers and ultimately audiences too. “It is an expensive art”, he acknowledges, but the money needed to continue producing and reinvesting in this music ultimately needs to come from audiences.

This isn’t a market that is engineered by what sells. Strictly speaking, it isn’t a market at all. Most indie bands have followings of a few hundred fans and are perfectly aware that their music is not geared to mainstream audiences. Some have formal training as vocalists or musicians; many don’t. Most are naturally tech-savvy enough to be able to turn to production and design sitting at a laptop. Essentially, as the members of Keeray Makoray tell me during a rehearsal break, it is a DIY gig and that is something most indie musicians appear happy to continue with.

The performer onstage at the moment can clearly out-Maiden Iron Maiden

“They [the artistes] interest me and I couldn’t tell you why”, Jamal chortles. And this sense of spontaneity, of not having to define or explain one’s likes and dislikes, appears to drive almost everyone there. Onstage at the moment is Shehzad Noor of Poor Rich Boy, who can clearly out-Maiden Iron Maiden, and Umer Khan, the band’s vocalist and songwriter, tells me that he is simply “making it up as he goes”. Even the bands’ names reflect an infectious pleasure in being deliberately clever without taking themselves too seriously: consider Basheer and the Pied Pipers. Red Blood Cat, which musician Masterjee Bumbu characterizes admiringly as “space jazz”, smacks of speakeasies. Keeray Makoray, I discover later, decided to call themselves this, sitting in a rickshaw en route to a Beatles tribute gig in Lahore.

It is easy enough to say that indie music is the snug domain of privileged young people who can effectively afford to balance university or day careers with their music – they range from university students to doctors, teachers, and lawyers. But this does not detract from their commitment or their musicianship. Even having recently returned from performing at the SXSW music festival in Austin in the US, Umer Khan says he would rather not treat his music as an all-consuming career. He is comfortable “pretending” – as he puts it self-effacingly – to be a professional by day and a musician by night.

Equally, it is immaterial that many such bands are not bound by their perhaps unwitting “choice” of language. As Waqas Khan, a former member of The Trip, points out to me, one reacts to the music, not just the words, which is why the choice to sing in English or Urdu or indeed any other language is more complex than assuming it is the language a musician is most comfortable with – and indeed that this should necessarily box him or her into a particular class or social group.

Sitting here on the grass, watching as the musician onstage belts out his pièce de résistance, as people around me talk and laugh as though it were a perfectly normal day in a perfectly normal country – just for now – and then as grey skies turn violently to rain, Storm in a Teacup peels away what music means. Making music is, at the heart of it, an intensely social act. It is perhaps the only art form that, in the unfettered shape of indie music, puts up no barriers between performer and audience. There is nothing to separate the two: not pages of words, not etiquette or protocol, not a cinema screen, not costume nor mask. Really, just the music.