Are Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif and Chief of Army Staff Gen Raheel Sharif set to undo many of the unpleasant policies of their predecessors? Is the ostensible civil-military consensus behind the March 11 raid on MQM headquarters Nine Zero and their display of unity at the Pakistan Day parade on March 23 a sign of the dawn of a new era, or will it just be another phase of tactical realignment spearheaded by the General Headquarters in Pakistan’s chequered history?

Unfortunately, the public views the GHQ as being more assertive and predominant in an extremely volatile situation arising out of political incompetence, insensitivity to public concern, and above all, patronage of rampant crime by political elites.

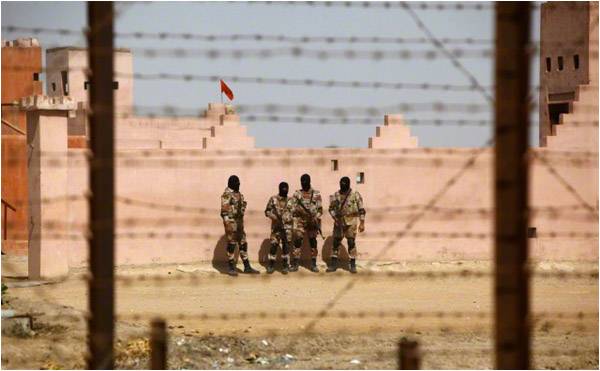

Back in September 2013, these circumstances had prompted the Supreme Court to direct law-enforcement agencies to eliminate the militant wings of political parties operating in Karachi. The Rangers did launch a clean-up operation, but the political will it required to be effective was still missing. On the face of it, the apex committee formed early this year provided the much-needed political ownership to what eventually led to the raid on the MQM headquarters – the culmination of the operation launched in late 2013 indeed. Intelligence outfits had gradually and increasingly zeroed in on the MQM for its role in criminal activities in the Karachi. Considerable mapping preceded before the rangers eventually dared to break through 21 barriers around Nine Zero.

The ensuing claims by the government, allegations by the PPP maverick Dr Zufliqar Mirza, and a statement by death-row convict Saulat Mirza, finally blew the lid off an unpleasant “open secret”; the direct or indirect role of major political parties in organized crime that had emerged as the single largest existential threat to Karachi. Security forces, including the corrupt police and the mighty Rangers, also benefited from the growing pie, it is said.

For years, politicians cried foul at the deteriorating law and order in Karachi and demanded firm action, but most exhibited little eagerness to go after the root causes, apparently because of their own financial stakes in the status quo. None would publicly admit any connection between political parties and about half a dozen lethal groups operating in various parts of the city, such as the Shoaib Group, the Lyari gangs, Rehman Dakait, Arhsad Pappu group, and the D-Gang.

These connections invariably undermined even the counter-terror strategies made by law-enforcement agencies, which fell flat also because of the presence of insiders within the civilian and military security establishment. It looked very much like the situation in Balochistan, where a number of informers for Baloch nationalists were found serving key security officials in various capacities, with severe implications for counter-insurgency operations.

The nexus between crime and politics has been equally debilitating for counter-criminal strategies. But it certainly isn’t surprising. What Pakistan faces today in Karachi and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, for instance, is the consequence of the policies of the past – General Ziaul Haq used the MQM to eliminate PPP, the PPP did take the sting out of MQM in mid 1990s, but for his petty personal interests, Gen Musharraf revived the MQM once he needed allies in Sindh against the PPP and PML-N.

The May 12, 2007 massacre of 45 people in Karachi was a glaring outcome of this policy, when the army chief and the president gave the MQM a carte blanche to prevent the then chief justice from entering Karachi. The Military Intelligence, officials had claimed then, got instructions for this carnage from Islamabad.

The situation on ground hardly changed in March 2008 when the PPP and MQM once again became partners in the Sindh government. Asif Zardari kept courting and cajoling the MQM. Meanwhile, crime surged as political expedience came in the way of a crackdown on the criminal syndicates patronized by various political parties. Elsewhere, the good mujahideen and Taliban who had been nurtured by the security establishment turned into monsters and kept multiplying.

Brandishing nationalistic, ethnic or religious flags, tentacles of these militants from Karachi to Khyber and Waziristan now extend deep into various arms of government including the security apparatus with deadly consequences for counter-terror and counter-insurgency operations. At the same time, these monsters enjoy patronage within political echelons and thereby often either remain untouched by the law or escape legal or punitive action. This deadly mix turns them into real existential threats to the country – more or less the way Afghan Taliban and affiliated groups bled the US-lead coalition forces.

After a long time though, the Pakistani civilian and military leadership appears to be relentless in their pursuit of criminal and terror syndicates – both politically connected or otherwise. They need to take this to its logical conclusion, without fear and favour. The socio-politically hazardous peace and political management policy that the civilian and militant establishments have pursued from the North to the South in the past cost this country heavily and severely undermined the fight against crime and terror.

Until we stop with short-term tactics such as playing one group against the other, Pakistan will remain volatile and prone to recurring political turmoil as well as vulnerable to the nexus of non-state actors and criminal syndicates. The country cannot afford expedient deals with criminals and terrorists for short-term gains any more. Fighting this all requires unflinching civil-military resolve for enforcing the rule of law in the country. Only then can the civilians and the military hope to undo the bitter legacies of the past and fend off the existential threats to Pakistan.

Unfortunately, the public views the GHQ as being more assertive and predominant in an extremely volatile situation arising out of political incompetence, insensitivity to public concern, and above all, patronage of rampant crime by political elites.

Back in September 2013, these circumstances had prompted the Supreme Court to direct law-enforcement agencies to eliminate the militant wings of political parties operating in Karachi. The Rangers did launch a clean-up operation, but the political will it required to be effective was still missing. On the face of it, the apex committee formed early this year provided the much-needed political ownership to what eventually led to the raid on the MQM headquarters – the culmination of the operation launched in late 2013 indeed. Intelligence outfits had gradually and increasingly zeroed in on the MQM for its role in criminal activities in the Karachi. Considerable mapping preceded before the rangers eventually dared to break through 21 barriers around Nine Zero.

The ensuing claims by the government, allegations by the PPP maverick Dr Zufliqar Mirza, and a statement by death-row convict Saulat Mirza, finally blew the lid off an unpleasant “open secret”; the direct or indirect role of major political parties in organized crime that had emerged as the single largest existential threat to Karachi. Security forces, including the corrupt police and the mighty Rangers, also benefited from the growing pie, it is said.

Until we stop with short-term tactics such as playing one group against the other, Pakistan will remain volatile

For years, politicians cried foul at the deteriorating law and order in Karachi and demanded firm action, but most exhibited little eagerness to go after the root causes, apparently because of their own financial stakes in the status quo. None would publicly admit any connection between political parties and about half a dozen lethal groups operating in various parts of the city, such as the Shoaib Group, the Lyari gangs, Rehman Dakait, Arhsad Pappu group, and the D-Gang.

These connections invariably undermined even the counter-terror strategies made by law-enforcement agencies, which fell flat also because of the presence of insiders within the civilian and military security establishment. It looked very much like the situation in Balochistan, where a number of informers for Baloch nationalists were found serving key security officials in various capacities, with severe implications for counter-insurgency operations.

The nexus between crime and politics has been equally debilitating for counter-criminal strategies. But it certainly isn’t surprising. What Pakistan faces today in Karachi and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, for instance, is the consequence of the policies of the past – General Ziaul Haq used the MQM to eliminate PPP, the PPP did take the sting out of MQM in mid 1990s, but for his petty personal interests, Gen Musharraf revived the MQM once he needed allies in Sindh against the PPP and PML-N.

The May 12, 2007 massacre of 45 people in Karachi was a glaring outcome of this policy, when the army chief and the president gave the MQM a carte blanche to prevent the then chief justice from entering Karachi. The Military Intelligence, officials had claimed then, got instructions for this carnage from Islamabad.

The situation on ground hardly changed in March 2008 when the PPP and MQM once again became partners in the Sindh government. Asif Zardari kept courting and cajoling the MQM. Meanwhile, crime surged as political expedience came in the way of a crackdown on the criminal syndicates patronized by various political parties. Elsewhere, the good mujahideen and Taliban who had been nurtured by the security establishment turned into monsters and kept multiplying.

Brandishing nationalistic, ethnic or religious flags, tentacles of these militants from Karachi to Khyber and Waziristan now extend deep into various arms of government including the security apparatus with deadly consequences for counter-terror and counter-insurgency operations. At the same time, these monsters enjoy patronage within political echelons and thereby often either remain untouched by the law or escape legal or punitive action. This deadly mix turns them into real existential threats to the country – more or less the way Afghan Taliban and affiliated groups bled the US-lead coalition forces.

After a long time though, the Pakistani civilian and military leadership appears to be relentless in their pursuit of criminal and terror syndicates – both politically connected or otherwise. They need to take this to its logical conclusion, without fear and favour. The socio-politically hazardous peace and political management policy that the civilian and militant establishments have pursued from the North to the South in the past cost this country heavily and severely undermined the fight against crime and terror.

Until we stop with short-term tactics such as playing one group against the other, Pakistan will remain volatile and prone to recurring political turmoil as well as vulnerable to the nexus of non-state actors and criminal syndicates. The country cannot afford expedient deals with criminals and terrorists for short-term gains any more. Fighting this all requires unflinching civil-military resolve for enforcing the rule of law in the country. Only then can the civilians and the military hope to undo the bitter legacies of the past and fend off the existential threats to Pakistan.