Largely lopsided agricultural policies between India and Pakistan turned out to be the pivotal reason behind Pakistan not granting the Most Favored Nation (MFN) status to India at the end of 2012. In September 2012, just a few months before Pakistan was to grant the MFN status to India, farmers associations across the country held protest demonstrations and called this decision ‘farmer unfriendly’.

The protesting farmers were of the view that Pakistani farmers would be at a serious disadvantage, firstly, against a highly subsidized agricultural sector in India and, secondly, the restricted market access for Pakistani produce into India. They opined that as the Government of Pakistan had withdrawn almost all the subsidies and supports in the agricultural sector, therefore, the local farmers would have to face adverse market outcomes and economic conditions in case a duty free access was given to Indian agricultural produce. Following this uproar, the Senate of Pakistan asked the government to take the farmers’ reservations into consideration before granting the MFN status to India.

Let us first critically examine the issue of Indian subsidies. Pakistani stakeholders do not think India is doing anything unjustifiable by subsidizing its agriculture. They say the Indians are just following their priorities. On the other hand, local agriculturalists are of the view that the government should not be subsidizing them and it is not their demand either. What they want is supportive policies addressing the issues of cost of production, regulation and enforcement of quality checks for inputs – especially seed, and access to formal credit and market dynamics. The local sector feels that without such facilities, the highly subsidized Indian exports will wipe out the local agricultural producers.

Conversely, the proponents of opening up trade with India think otherwise. Their main question is, why would the Indian government subsidize Pakistani consumers in key staple food items? They are of the view that opening up trade will be beneficial, although in some products Pakistani producers may face tough competition.

[quote]The negative impact on large crops will not be as significant as that on fresh vegetables[/quote]

The above two claims have been analyzed in a study conducted by Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) and it deduced that the claim made by local farmers holds true, but not for all agricultural products. The study suggests that the production of perishable fruits and vegetables (tomatoes, capsicum, ginger etc) have been badly hit by cheaper Indian imports and they have made significant inroads into the key markets of Punjab.

The study further says that a direct impact of this surge in imports from India was felt in the tunnel farming sector. Tunnel farming in Punjab had gone up to 55,000 acres and a good number of off-season vegetables were being sold in the market. However, since the start of the imports from India, this acreage has reduced to 35,000. This damage has not only been felt in the private sectors, as several farms have been closed, but also the government got the shock as well, as it had heavily invested money in subsidizing the cost of setting up such farms.

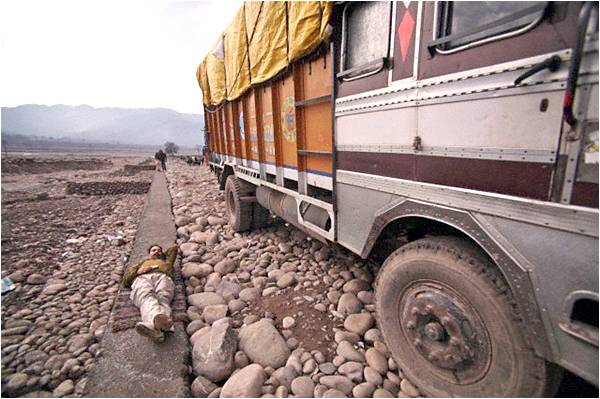

However, the LUMS study suggests that this impact was not due to the MFN issue. It was due to the opening up of duty free import of 137 items (all agricultural products) through Wagah-Attari border. This import was basically allowed to control the consumer inflation in Pakistan for the basic food items. However, this policy had mixed effects.

A remedial strategy to control this influx of imports is to have stricter requirements on the quantity of arsenic in vegetables. Since Indian agriculturalists get the fertilizers at a highly subsidized rate, they use it in excessive quantity, which increases the amount of arsenic in the fresh vegetables, which is detrimental to health. By enforcing stricter standards for arsenic, the imports would automatically be diminished.

Contrary to the situation of fresh vegetables, the study reveals that the negative impact on local produce in case of large crops would not be as significant as in case of fresh vegetables. The production level of larger crops in India is phenomenal as compared to Pakistan in absolute terms, but the per capita production in Pakistan is more than that of India. A large part of these staple crops is consumed by the local consumers and India is not a big exporter of these crops. So, we can say that the subsidy is specifically related to address the food security problems in India and not for export purposes. So, it would be reasonable to conclude that duty free imports from India would be a threat to the fresh vegetable sector and not for the large crops.

Now let us discuss the issue of restricted market access to India. One should be very categorical in saying that the imposition of Non-Tariff Barriers (NTBs) by the Indian government is a major impediment in exporting agricultural produce to India. For agriculture, India has two major NTBs – quarantine, and the SPS (Sanitary and PhytoSanitary) requirements. The stakeholders are of the view that Pakistan had a major glut in potato crop in 2013, but could not export potato to India because of SPS issues.

According to World Bank (WB), the Overall Trade Restrictiveness Index (OTRI), comprising both tariff and non-tariff barriers, in agriculture in India was 69.5% compared to only 5.8% for Pakistan.

Lastly, another real NTB is visa regime from the Indian side. Pakistani businessmen are allowed on arrival a visa of up to six Indian cities excluding Punjab. If farmers from Pakistan have to sell their agricultural produce in India, the best market is Amritsar. So, due to this strange visa restriction, farmers are unable to sell their perishable agricultural products to India.

The protesting farmers were of the view that Pakistani farmers would be at a serious disadvantage, firstly, against a highly subsidized agricultural sector in India and, secondly, the restricted market access for Pakistani produce into India. They opined that as the Government of Pakistan had withdrawn almost all the subsidies and supports in the agricultural sector, therefore, the local farmers would have to face adverse market outcomes and economic conditions in case a duty free access was given to Indian agricultural produce. Following this uproar, the Senate of Pakistan asked the government to take the farmers’ reservations into consideration before granting the MFN status to India.

Let us first critically examine the issue of Indian subsidies. Pakistani stakeholders do not think India is doing anything unjustifiable by subsidizing its agriculture. They say the Indians are just following their priorities. On the other hand, local agriculturalists are of the view that the government should not be subsidizing them and it is not their demand either. What they want is supportive policies addressing the issues of cost of production, regulation and enforcement of quality checks for inputs – especially seed, and access to formal credit and market dynamics. The local sector feels that without such facilities, the highly subsidized Indian exports will wipe out the local agricultural producers.

Conversely, the proponents of opening up trade with India think otherwise. Their main question is, why would the Indian government subsidize Pakistani consumers in key staple food items? They are of the view that opening up trade will be beneficial, although in some products Pakistani producers may face tough competition.

[quote]The negative impact on large crops will not be as significant as that on fresh vegetables[/quote]

The above two claims have been analyzed in a study conducted by Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) and it deduced that the claim made by local farmers holds true, but not for all agricultural products. The study suggests that the production of perishable fruits and vegetables (tomatoes, capsicum, ginger etc) have been badly hit by cheaper Indian imports and they have made significant inroads into the key markets of Punjab.

The study further says that a direct impact of this surge in imports from India was felt in the tunnel farming sector. Tunnel farming in Punjab had gone up to 55,000 acres and a good number of off-season vegetables were being sold in the market. However, since the start of the imports from India, this acreage has reduced to 35,000. This damage has not only been felt in the private sectors, as several farms have been closed, but also the government got the shock as well, as it had heavily invested money in subsidizing the cost of setting up such farms.

However, the LUMS study suggests that this impact was not due to the MFN issue. It was due to the opening up of duty free import of 137 items (all agricultural products) through Wagah-Attari border. This import was basically allowed to control the consumer inflation in Pakistan for the basic food items. However, this policy had mixed effects.

A remedial strategy to control this influx of imports is to have stricter requirements on the quantity of arsenic in vegetables. Since Indian agriculturalists get the fertilizers at a highly subsidized rate, they use it in excessive quantity, which increases the amount of arsenic in the fresh vegetables, which is detrimental to health. By enforcing stricter standards for arsenic, the imports would automatically be diminished.

Contrary to the situation of fresh vegetables, the study reveals that the negative impact on local produce in case of large crops would not be as significant as in case of fresh vegetables. The production level of larger crops in India is phenomenal as compared to Pakistan in absolute terms, but the per capita production in Pakistan is more than that of India. A large part of these staple crops is consumed by the local consumers and India is not a big exporter of these crops. So, we can say that the subsidy is specifically related to address the food security problems in India and not for export purposes. So, it would be reasonable to conclude that duty free imports from India would be a threat to the fresh vegetable sector and not for the large crops.

Now let us discuss the issue of restricted market access to India. One should be very categorical in saying that the imposition of Non-Tariff Barriers (NTBs) by the Indian government is a major impediment in exporting agricultural produce to India. For agriculture, India has two major NTBs – quarantine, and the SPS (Sanitary and PhytoSanitary) requirements. The stakeholders are of the view that Pakistan had a major glut in potato crop in 2013, but could not export potato to India because of SPS issues.

According to World Bank (WB), the Overall Trade Restrictiveness Index (OTRI), comprising both tariff and non-tariff barriers, in agriculture in India was 69.5% compared to only 5.8% for Pakistan.

Lastly, another real NTB is visa regime from the Indian side. Pakistani businessmen are allowed on arrival a visa of up to six Indian cities excluding Punjab. If farmers from Pakistan have to sell their agricultural produce in India, the best market is Amritsar. So, due to this strange visa restriction, farmers are unable to sell their perishable agricultural products to India.