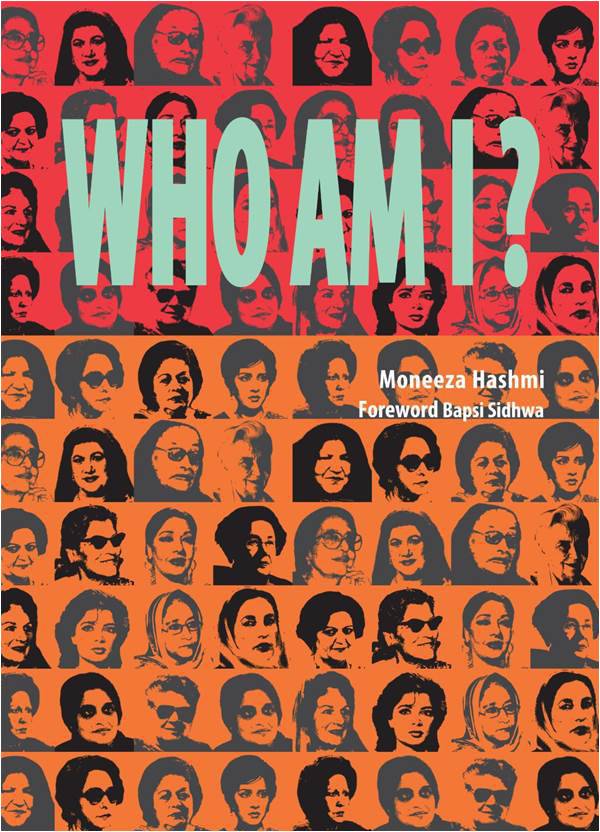

‘Who Am I?’ is the title of Moneeza Hashmi’s collection of twenty interviews of notable Pakistani women. Who are these women, we ask, and the answer is that they are the leading ladies- in many cases amongst the pioneers- in the areas of film, music, literature, politics and social work in Pakistan. Adapted and translated from Hashmi’s late 1990’s PTV series Tum Jo Chaho Tu Suno, these interviews provide brief glimpses into the lives of these women; they delve into their childhoods, seek their motivations and try to discover how they balance their personal and professional lives.

“Creativity for me is a passion to explore (sic),” says Hashmi and thus creativity and the artist’s unique relationship to the world is a theme which is repeatedly explored with writers, musicians and artists as each offers a look into her own distinctive way of experiencing and creating art. Abida Parveen tells us how, when she is singing, she feels “like I am there but actually am somewhere else,” similarly, Bano Qudsia describes those who are in the throes of creativity as moving to “another dimension, another world.” Qudsia also speaks of the loneliness suffered by creative people while Bapsi Sidhwa explains how a lonely childhood spent reading equipped her to be a writer while a trip along the Karakoram Highway much later in life lent her compelling images and stories which soon manifested themselves as her first novel. Malika Pukhraj claims that music is her “life and blood, I recognize the entire universe through music”.

[quote]Two of these women have trumped societal expectations entirely and remained consistently unmarried[/quote]

One of the things that most drew my attention in this volume is how these twenty successful professional Pakistani women have managed to deal with society’s expectations of women as married, ‘settled’ homemakers, along with their own understanding of their responsibilities as mothers and wives. Two of these women have trumped societal expectations entirely and remained consistently unmarried: the film actress Babra Sharif and the extraordinary political activist, member of the Pakistan Movement, social worker and businesswoman hailing from Mardan, Zari Sarfaraz. All of the rest, except for social worker Ruth Pfau who is a nun, are or have been married at some point. It comes across that many feel that they have not been able to fulfil their obligations as mothers or that they have to put their work aside to attend to their roles as wives and mothers. Bapsi Sidhwa notes that the latter overtook her at some point to the extent that “writing was not considered very worthy of my time.” Likewise, film actress Bahar Begum felt that “film and married life could not co-exist,” and left acting only to return after her children had grown up and she had obtained a divorce. Farida Khanum also put her singing career on halt for a certain time to address domestic concerns and politician Naseem Wali Khan feels that she was unable to do complete justice by her motherly and wifely duties, as does Bano Qudsia. While artist Salima Hashmi admits to sometimes feeling guilty when she thinks she has neglected her family, she lays out the deal very well as she explicates that women need to decide whether their art or their work is essential to them and their sense of self and if it is the latter, they need to make those around them understand this and support and accommodate them.

[quote]“I came back and mentioned this to Asif (Ali Zardari) who told me this could not happen in Pakistan!”[/quote]

How practicable has Hashmi’s solution been for these women? Benazir Bhutto, in her interview, also puts forth the belief that women must be given all those means which make them independent and enable them to choose their own path, regardless of whether they are housewives with domestic responsibilities. However, she goes on to relate an incident in which she asked the Norwegian Prime Minister how she coped with her domestic duties and found out that her husband had taken many of the responsibilities upon himself. But Prime Minister Bhutto says that when “I came back and mentioned this to Asif (Ali Zardari) his answer was that this could not happen in Pakistan!” And yet, the examples of Salima Hashmi as well as Malika Pukhraj, who claims complete cooperation from her husband, film actress Sabiha Khanum, who held her own with regard to her career and political activist Tahira Mazhar show us that the difficult and elusive balance between home and career has been possible for the women of this generation.

As readers we gain a privileged insight into the lives of these women through these interviews. However, most likely due to the fact that they were adapted from a show broadcast on national television, several of them feel slightly tame and truncated - it would have been lovely to hear more from Abida Parveen, or gotten to know about Swaran Lata’s work in the film industry in pre-partition times, as well as why she chose to marry a Muslim man and convert to Islam. Equally, Zari Sarfaraz’s views on marriage and domestic life would have been fascinating to give ear to.

Each interview is preceded by an introduction of sorts by Hashmi in which she often talks about her views of the interviewee and the experience of interviewing them. Quite often, extraneous details make their way into this section, such as long-winded descriptions of Hashmi’s own experiences at the cinema as a young girl and lists of her favourite actors. Additionally, some rather bizarre details crop up; for example, referring to Babra Sharif’s short stature, Hashmi says “Babra Sharif suffers from a lack of torso,” about Shamim Ara she passes the rather harsh judgment that “no one could ever call her glamorous or even beautiful,” similarly, she comments that Sabiha Khanum has “a full figure without being overly buxom or vulgar.” The implication of this last statement seems to be that having a full figure or being buxom connotes vulgarity, but most likely these are mistakes which passed under the radar of a myopic editor. The utter lack of editing rigour in this volume is not just restricted to the content; throughout the book full stops are liberally sprinkled at the most inappropriate occasions, commas often fail to materialize when required, the first letters of random nouns are mystifyingly rendered in uppercase, subjects are sometimes found in conflict with their verbs and some spellings tend to go awry.

Yet, ‘Who Am I?’ provides an enriching glimpse into the lives of twenty Pakistani women who have excelled at what they did and left legacies which we can look up to. To be able to partake in their thoughts, ideas, achievements, anxieties and struggles through the pages of this book is a valuable and instructive experience.

“Creativity for me is a passion to explore (sic),” says Hashmi and thus creativity and the artist’s unique relationship to the world is a theme which is repeatedly explored with writers, musicians and artists as each offers a look into her own distinctive way of experiencing and creating art. Abida Parveen tells us how, when she is singing, she feels “like I am there but actually am somewhere else,” similarly, Bano Qudsia describes those who are in the throes of creativity as moving to “another dimension, another world.” Qudsia also speaks of the loneliness suffered by creative people while Bapsi Sidhwa explains how a lonely childhood spent reading equipped her to be a writer while a trip along the Karakoram Highway much later in life lent her compelling images and stories which soon manifested themselves as her first novel. Malika Pukhraj claims that music is her “life and blood, I recognize the entire universe through music”.

[quote]Two of these women have trumped societal expectations entirely and remained consistently unmarried[/quote]

One of the things that most drew my attention in this volume is how these twenty successful professional Pakistani women have managed to deal with society’s expectations of women as married, ‘settled’ homemakers, along with their own understanding of their responsibilities as mothers and wives. Two of these women have trumped societal expectations entirely and remained consistently unmarried: the film actress Babra Sharif and the extraordinary political activist, member of the Pakistan Movement, social worker and businesswoman hailing from Mardan, Zari Sarfaraz. All of the rest, except for social worker Ruth Pfau who is a nun, are or have been married at some point. It comes across that many feel that they have not been able to fulfil their obligations as mothers or that they have to put their work aside to attend to their roles as wives and mothers. Bapsi Sidhwa notes that the latter overtook her at some point to the extent that “writing was not considered very worthy of my time.” Likewise, film actress Bahar Begum felt that “film and married life could not co-exist,” and left acting only to return after her children had grown up and she had obtained a divorce. Farida Khanum also put her singing career on halt for a certain time to address domestic concerns and politician Naseem Wali Khan feels that she was unable to do complete justice by her motherly and wifely duties, as does Bano Qudsia. While artist Salima Hashmi admits to sometimes feeling guilty when she thinks she has neglected her family, she lays out the deal very well as she explicates that women need to decide whether their art or their work is essential to them and their sense of self and if it is the latter, they need to make those around them understand this and support and accommodate them.

[quote]“I came back and mentioned this to Asif (Ali Zardari) who told me this could not happen in Pakistan!”[/quote]

How practicable has Hashmi’s solution been for these women? Benazir Bhutto, in her interview, also puts forth the belief that women must be given all those means which make them independent and enable them to choose their own path, regardless of whether they are housewives with domestic responsibilities. However, she goes on to relate an incident in which she asked the Norwegian Prime Minister how she coped with her domestic duties and found out that her husband had taken many of the responsibilities upon himself. But Prime Minister Bhutto says that when “I came back and mentioned this to Asif (Ali Zardari) his answer was that this could not happen in Pakistan!” And yet, the examples of Salima Hashmi as well as Malika Pukhraj, who claims complete cooperation from her husband, film actress Sabiha Khanum, who held her own with regard to her career and political activist Tahira Mazhar show us that the difficult and elusive balance between home and career has been possible for the women of this generation.

As readers we gain a privileged insight into the lives of these women through these interviews. However, most likely due to the fact that they were adapted from a show broadcast on national television, several of them feel slightly tame and truncated - it would have been lovely to hear more from Abida Parveen, or gotten to know about Swaran Lata’s work in the film industry in pre-partition times, as well as why she chose to marry a Muslim man and convert to Islam. Equally, Zari Sarfaraz’s views on marriage and domestic life would have been fascinating to give ear to.

Each interview is preceded by an introduction of sorts by Hashmi in which she often talks about her views of the interviewee and the experience of interviewing them. Quite often, extraneous details make their way into this section, such as long-winded descriptions of Hashmi’s own experiences at the cinema as a young girl and lists of her favourite actors. Additionally, some rather bizarre details crop up; for example, referring to Babra Sharif’s short stature, Hashmi says “Babra Sharif suffers from a lack of torso,” about Shamim Ara she passes the rather harsh judgment that “no one could ever call her glamorous or even beautiful,” similarly, she comments that Sabiha Khanum has “a full figure without being overly buxom or vulgar.” The implication of this last statement seems to be that having a full figure or being buxom connotes vulgarity, but most likely these are mistakes which passed under the radar of a myopic editor. The utter lack of editing rigour in this volume is not just restricted to the content; throughout the book full stops are liberally sprinkled at the most inappropriate occasions, commas often fail to materialize when required, the first letters of random nouns are mystifyingly rendered in uppercase, subjects are sometimes found in conflict with their verbs and some spellings tend to go awry.

Yet, ‘Who Am I?’ provides an enriching glimpse into the lives of twenty Pakistani women who have excelled at what they did and left legacies which we can look up to. To be able to partake in their thoughts, ideas, achievements, anxieties and struggles through the pages of this book is a valuable and instructive experience.