Last year, Pakistan faced unprecedented rainfall run-off and subsequent river discharges which triggered the most severe flooding in Pakistan’s recent history. It affected up to 33 million people, pushing families to the brink of survival. The disaster continues to unfold today as the floodwater has not receded in some areas of Sindh and Balochistan as yet.

The climate projections presented in the 6th Assessment Report of Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) indicate that South Asia will continue to be affected by increasingly intense monsoon seasons, which are likely to cause even more floods in the future. This has evidently already taken place in Pakistan, where the disastrous floods were preceded by intense and prolonged heat waves. Usually, in Pakistan, the monsoon season ends after 3-4 cycles, but in 2022, it experienced more than 8 cycles of monsoon.

The science linking climate change and more intense monsoons is quite simple. Global warming is making air and sea temperatures rise, leading to more evaporation. Warmer air can hold more moisture, making monsoon rainfall more intense.

The last monsoon season and the subsequent flooding were not normal, as new rainfall records were set in various parts of the country. By August 25, Pakistan had received nearly 15 inches (375 mm) of rainfall, almost three times higher than the national 30-year average of 5 inches (130 mm). Balochistan province received 5 times its average 30-year rainfall. The consequences of the 2022 floods are far-reaching and extraordinary, as they have engendered the imminent threat of food insecurity, water-borne diseases, malnutrition, and social unrest in Pakistan.

The erratic monsoon patterns are also indicative of the southward shift of the monsoons for Pakistan under the changing climate. Due to this shift, a significant portion of the 2022 floods originated from the non-perennial hill-torrent streams along the semi-arid Koh-e-Suleman and Kirthar mountain ranges, causing devastating inundations before draining into the Indus River.

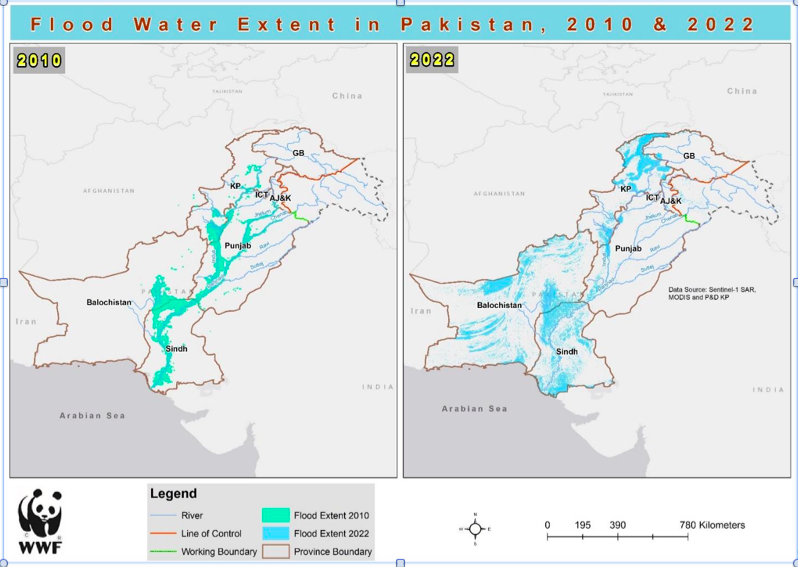

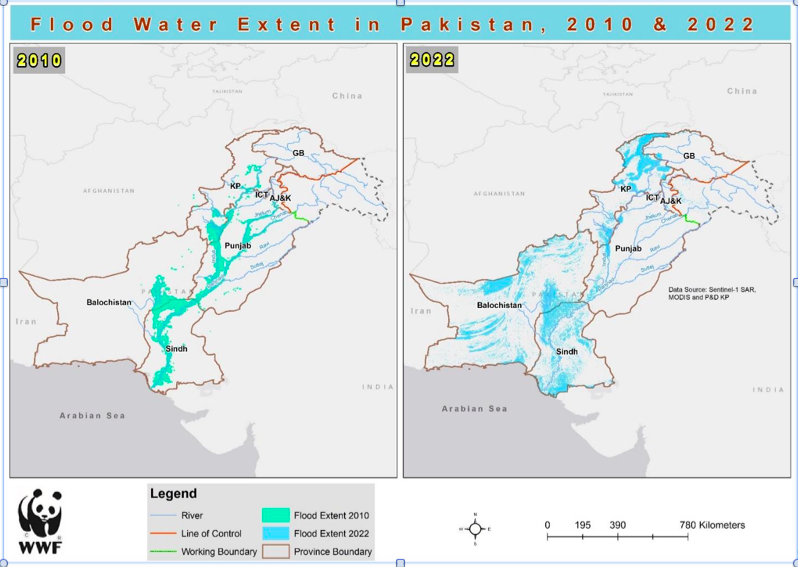

Soon after the flooding comparisons began to be made between the 2022 and 2010 floods. The 2010 floods began in late July, resulting from heavy monsoon rains in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Sindh, and parts of Balochistan. About 20 percent of the land area of Pakistan and over 20 million people were affected. Total loss of lives stood at 1,985 with Sindh being the worst affected, followed by Punjab. Experts called it one of the worst humanitarian disasters in the history of Pakistan.

Twelve years later, massive flooding has forced analysts and political leaders alike to search for new adjectives that appropriately describe the devastation caused by monsoon rains, with United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres calling the inundation “epochal level”.

The 2022 floods have affected large swaths of agricultural land and settlements in Sindh, Balochistan, Punjab, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) provinces of Pakistan. About 81 districts in Sindh, Punjab, Balochistan, and KP were notified as ‘calamity hit’ with close to 1,400 dead since June 14, 2022, according to data released by the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA).

The International Rescue Committee (IRC) believes that the 2022 floods have created more havoc than the 2010 floods. There are many similarities between the two events. The 2010 floods had severely dented the GDP growth that reached the low of 2.58 percent. Similarly, the current flooding, according to estimates, may also bring down the GDP growth level to less than 3 percent and the national poverty rate will increase by 3.7-4.0 percent, pushing between 8.4 and 9.1 million people into poverty, as a direct consequence of the 2022 floods.

One clear player in both the 2010 and 2022 disasters is La Niña. La Niña is a climate pattern that occurs in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. During a La Niña event, the trade winds in the Pacific Ocean blow stronger than usual, which causes the ocean surface to cool down. This in turn affects the atmospheric circulation patterns, which can have global impacts on weather patterns. Both years featured La Niña conditions during northern summer. In fact, for the months of May through July, the two strongest La Niña years of the 21st century happened to be 2010 and 2022.

There’s clearly more than La Niña at work, though, given the severity of the Pakistan flood impacts in these two years versus major flood events of decades past. Researchers from the World Weather Attribution group say climate change may have increased the intensity of rainfall. What we saw in Pakistan is exactly what climate projections have been predicting for years. It's also in-line with historical records showing that heavy rainfall has dramatically increased in the region since humans started emitting large amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

Current efforts in Pakistan to manage severe floods and droughts caused by climate change are largely reactive and rely on grey infrastructure to address the impacts of these events on the country’s population, economy and ecosystems. This is due to the country's resource and economic constraints, high level of indebtedness, and reliance on intermittent donor financing for disaster recovery which prevent the government of Pakistan from making proactive investments in flood and drought risk reduction interventions that provide sustainable benefits.

In addition to these constraints, Pakistan’s current policy and regulatory instruments for water resource management — namely the National Water Policy, National Adaptation Plan (NAP), and Provincial Adaptation Plans — do not consider Ecosystem based Adaptation (EbA) and green infrastructure interventions to help reduce Pakistan’s climate vulnerabilities. Public sector reform around flood and water resources management is needed which includes EbA and green infrastructure interventions to generate evidence of their benefits in reducing the impacts of floods and droughts, and formal procedures are adopted to prioritise these interventions and diversify public sector solutions to managing floods and droughts in Pakistan. The absence of such reforms in Pakistan’s business-as-usual water resources management approach will continue to exacerbate communities’ vulnerability to extreme events.

WWF-Pakistan has been working on various projects to advocate and implement nature-based solutions for integrated flood risk management in Pakistan. One of the projects has been submitted to the UN’s Green Climate Fund and is known as ‘Recharge Pakistan”. The project focuses on recharging our aquifers and wetlands and protecting our vital Indus River from different threats to create an enabling environment for climate action in Pakistan.

Project interventions, such as Ecosystem based Adaptation (EbA) and Green Infrastructure (GI), will be implemented across Pakistan. The EbA-solutions are defined as actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural or modified ecosystems that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, simultaneously providing human well-being and biodiversity benefits. For example, planting trees in areas prone to flooding can help prevent erosion and absorb excess water and restore pathways to nearby wetlands. Whereas GI refers to any vegetative or natural material infrastructure system which enhances the natural environment through direct or indirect means. It is the range of measures that use plant or soil systems, permeable surfaces or substrates, stormwater harvest and reuse, or landscaping to store, infiltrate, or evapotranspiration stormwater and reduce flows.

Floods are a part of our landscape, and indeed our heritage. Technocratic solutions to our water woes have been proven to be inadequate in addressing the multitude of challenges. We need to turn to a more holistic outlook, one based on the sanctity of natural ecology, geography and topography, and one that values human agency and lived experience.

The author is Manager, Freshwater Programme, WWF-Pakistan

The climate projections presented in the 6th Assessment Report of Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) indicate that South Asia will continue to be affected by increasingly intense monsoon seasons, which are likely to cause even more floods in the future. This has evidently already taken place in Pakistan, where the disastrous floods were preceded by intense and prolonged heat waves. Usually, in Pakistan, the monsoon season ends after 3-4 cycles, but in 2022, it experienced more than 8 cycles of monsoon.

The science linking climate change and more intense monsoons is quite simple. Global warming is making air and sea temperatures rise, leading to more evaporation. Warmer air can hold more moisture, making monsoon rainfall more intense.

The last monsoon season and the subsequent flooding were not normal, as new rainfall records were set in various parts of the country. By August 25, Pakistan had received nearly 15 inches (375 mm) of rainfall, almost three times higher than the national 30-year average of 5 inches (130 mm). Balochistan province received 5 times its average 30-year rainfall. The consequences of the 2022 floods are far-reaching and extraordinary, as they have engendered the imminent threat of food insecurity, water-borne diseases, malnutrition, and social unrest in Pakistan.

The erratic monsoon patterns are also indicative of the southward shift of the monsoons for Pakistan under the changing climate. Due to this shift, a significant portion of the 2022 floods originated from the non-perennial hill-torrent streams along the semi-arid Koh-e-Suleman and Kirthar mountain ranges, causing devastating inundations before draining into the Indus River.

Soon after the flooding comparisons began to be made between the 2022 and 2010 floods. The 2010 floods began in late July, resulting from heavy monsoon rains in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Sindh, and parts of Balochistan. About 20 percent of the land area of Pakistan and over 20 million people were affected. Total loss of lives stood at 1,985 with Sindh being the worst affected, followed by Punjab. Experts called it one of the worst humanitarian disasters in the history of Pakistan.

Twelve years later, massive flooding has forced analysts and political leaders alike to search for new adjectives that appropriately describe the devastation caused by monsoon rains, with United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres calling the inundation “epochal level”.

The 2022 floods have affected large swaths of agricultural land and settlements in Sindh, Balochistan, Punjab, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) provinces of Pakistan. About 81 districts in Sindh, Punjab, Balochistan, and KP were notified as ‘calamity hit’ with close to 1,400 dead since June 14, 2022, according to data released by the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA).

The International Rescue Committee (IRC) believes that the 2022 floods have created more havoc than the 2010 floods. There are many similarities between the two events. The 2010 floods had severely dented the GDP growth that reached the low of 2.58 percent. Similarly, the current flooding, according to estimates, may also bring down the GDP growth level to less than 3 percent and the national poverty rate will increase by 3.7-4.0 percent, pushing between 8.4 and 9.1 million people into poverty, as a direct consequence of the 2022 floods.

One clear player in both the 2010 and 2022 disasters is La Niña. La Niña is a climate pattern that occurs in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. During a La Niña event, the trade winds in the Pacific Ocean blow stronger than usual, which causes the ocean surface to cool down. This in turn affects the atmospheric circulation patterns, which can have global impacts on weather patterns. Both years featured La Niña conditions during northern summer. In fact, for the months of May through July, the two strongest La Niña years of the 21st century happened to be 2010 and 2022.

There’s clearly more than La Niña at work, though, given the severity of the Pakistan flood impacts in these two years versus major flood events of decades past. Researchers from the World Weather Attribution group say climate change may have increased the intensity of rainfall. What we saw in Pakistan is exactly what climate projections have been predicting for years. It's also in-line with historical records showing that heavy rainfall has dramatically increased in the region since humans started emitting large amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

Current efforts in Pakistan to manage severe floods and droughts caused by climate change are largely reactive and rely on grey infrastructure to address the impacts of these events on the country’s population, economy and ecosystems. This is due to the country's resource and economic constraints, high level of indebtedness, and reliance on intermittent donor financing for disaster recovery which prevent the government of Pakistan from making proactive investments in flood and drought risk reduction interventions that provide sustainable benefits.

In addition to these constraints, Pakistan’s current policy and regulatory instruments for water resource management — namely the National Water Policy, National Adaptation Plan (NAP), and Provincial Adaptation Plans — do not consider Ecosystem based Adaptation (EbA) and green infrastructure interventions to help reduce Pakistan’s climate vulnerabilities. Public sector reform around flood and water resources management is needed which includes EbA and green infrastructure interventions to generate evidence of their benefits in reducing the impacts of floods and droughts, and formal procedures are adopted to prioritise these interventions and diversify public sector solutions to managing floods and droughts in Pakistan. The absence of such reforms in Pakistan’s business-as-usual water resources management approach will continue to exacerbate communities’ vulnerability to extreme events.

WWF-Pakistan has been working on various projects to advocate and implement nature-based solutions for integrated flood risk management in Pakistan. One of the projects has been submitted to the UN’s Green Climate Fund and is known as ‘Recharge Pakistan”. The project focuses on recharging our aquifers and wetlands and protecting our vital Indus River from different threats to create an enabling environment for climate action in Pakistan.

Project interventions, such as Ecosystem based Adaptation (EbA) and Green Infrastructure (GI), will be implemented across Pakistan. The EbA-solutions are defined as actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural or modified ecosystems that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, simultaneously providing human well-being and biodiversity benefits. For example, planting trees in areas prone to flooding can help prevent erosion and absorb excess water and restore pathways to nearby wetlands. Whereas GI refers to any vegetative or natural material infrastructure system which enhances the natural environment through direct or indirect means. It is the range of measures that use plant or soil systems, permeable surfaces or substrates, stormwater harvest and reuse, or landscaping to store, infiltrate, or evapotranspiration stormwater and reduce flows.

Floods are a part of our landscape, and indeed our heritage. Technocratic solutions to our water woes have been proven to be inadequate in addressing the multitude of challenges. We need to turn to a more holistic outlook, one based on the sanctity of natural ecology, geography and topography, and one that values human agency and lived experience.

The author is Manager, Freshwater Programme, WWF-Pakistan