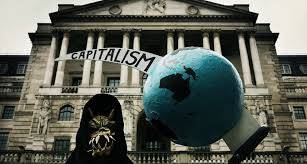

How should capitalism be defined in the 21st century and what does the future hold for it? Although much has changed over the years since the term was first used at the end of the 19th century and optimists talk of a fourth industrial revolution despite the adverse impact and stress of the Covid-19 pandemic and high energy prices caused by the war in Ukraine, extant capitalist societies are still characterized by five core features that go back to the early years of capitalism. These are the ownership of private property and assets without limit, freedom of choice for the producers and consumers of goods and services, profit-maximization without limit as the governing criterion for setting up and operating an enterprise, regardless of the damage that it may inflict on the wider physical and social environment and a strictly limited role of the State in the economy, confined to the maintenance of price and exchange rate stability.

Having said this, defining capitalism even in this simplified way still remains controversial. Unlike natural phenomena, the concepts and jargon used in analysing its main features except, say, in some narrow, purely technical areas, do not enjoy universal agreement. They are the products of their time and place, including how the idea of the nation-state came into being and how national rivalries and competition became a defining feature of global politics and of the global economy over the last two centuries or more.

Today, to many observers the UK economy represents what a mature capitalist society might look like, and given that, should shed light on capitalism’s future. Indeed, the UK provides us with a quasi-lab experiment as to how capitalism has evolved over the years, what trade-offs have occurred, its current travails, what have been the resultant costs and benefits for different sections of UK society and whether it conforms to any predicted pattern of evolution. It should therefore hold lessons for other societies and countries.

It would do us well to remember here that economics and political philosophy have always been closely intertwined and the prevailing philosophical climate of any epoch undoubtedly has had a profound bearing on the development of ideas and, hence, for state policy formulation. Against this background, it would be well to remember, too, that over the last two or three centuries nations and societies have evolved in a very erratic manner so that, just taking the relationship between the State and economic life - disregarding the impact of colonialism on the development of capitalism for the time being - the experience of Western Europe, East and South East Asia, especially China, and of the US differs fundamentally from that of the UK. In addition, their varying attitudes to private property and State intervention also differ so that we already have to distinguish between several different types of capitalisms.

The only phenomena that a social scientist might then validly compare are overall outcomes, i.e. assessing how individual nations/societies have fared in terms of collective, societal welfare within the parameters of their own socio-political arrangements (Joan Robinson 1970).

It would do us well to remember here that economics and political philosophy have always been closely intertwined and the prevailing philosophical climate of any epoch undoubtedly has had a profound bearing on the development of ideas and, hence, for state policy formulation.

Of the five criteria listed above, the degree of private property ownership, including any limitations on the extent of State intervention, is where the greatest variations exist on a cross-country basis. The relative extent and depth of State intervention has been determined not just by ideological considerations, but by a host of other factors such as war, internal conflict, external shocks, systemic market failures and/or an adverse attitude to risk on the part of private investors leading to under-investment in particular sectors of each economy. However, the classical belief system purported to suggest that, pace Adam Smith, even the moral problem – what we would call issues of social justice today - would be best solved within capitalism if every individual continued to pursue his or her own interest.

In this belief system individual utility maximization would not be inimical to maximizing the collective welfare of society and that in reality any State intervention, however well-intentioned, would only do harm to this happy state of affairs by distorting markets and incentives.

Capital has been able to improve its earning power vis-à-vis both labor and land in the value creation process. There can be little doubt that this could only have been politically achieved; it is certainly not the outcome of any arms-length competitive forces. By weakening trade unions and then constructing a supportive legal framework through anti-union laws, capital has succeeded in obtaining a higher share of the rewards of value creation in the global economy.

It has to be remembered that in the background is the contentious question of how value is created in society and how, in doing so, the different factors of production are rewarded; for, it is the process of value creation that has given rise to opportunities for the development of monopolization and rent-seeking in the modern capitalist economy, developments that are more fully discussed with respect to the UK economy later in this paper. In classical economics, it was assumed that all three factors contributed to value creation and the ensuing rewards then tended to converge towards equality in a fully competitive economy, depending upon the relative proportions in which the factors had been used in creating value. But, few economies today are, or ever have been, fully competitive. Indeed, competition exists only in a few sectors of most economies.

As a result, factor rewards can and have been politically and even legally manipulated (Joan Robinson 1933). This suggests that any one of the factors could be disproportionately rewarded over long periods of time in the process of value creation. Over the years, for example, factor rewards have tended to remain relatively stable but during the last three or more decades the share of labor has been going down, while concomitantly, the share of corporate profits has been going up.

What this means is that capital has been able to improve its earning power vis-à-vis both labor and land in the value creation process. There can be little doubt that this could only have been politically achieved; it is certainly not the outcome of any arms-length competitive forces. By weakening trade unions and then constructing a supportive legal framework through anti-union laws, capital has succeeded in obtaining a higher share of the rewards of value creation in the global economy. For most people, the process appears to be inexorable about which very little can be done. But, in fact, it is bound up with the deliberate actions of the ruling elites in capitalist societies and how they have sought to protect their status, privileges and power as capitalism has evolved over the last 70 years. To understand how this has come to pass we begin the story in 1945 when World War II ended and the UK, as one of the victors, had to fashion a new future.

The ending of the pro-welfare post-World War II consensus

Historically, the UK had little or no state intervention before World War II except at the local government level. The War not only magnified the extent of state intervention in the economy, but made it possible for the incoming Labour government to drive the process forward in 1945 that was partly the result of ideology that enshrined its welfare agenda, and was partly the result of the wartime economy of controls and rationing that the government inherited after the War ended. In due course, the capitalism that characterized the UK became a forerunner of the more egalitarian socio-economic settlement that emerged over much of Western Europe after World War II and came to be called social democracy.

In the UK, academic approval for higher public spending in the 1930s had been initially proposed by Keynes (and others before him) to tackle the high and chronic unemployment that affected the UK economy following the stock market crash in the US in 1929. So relaxed was Keynes about the role of public spending in the economy that in a wartime broadcast on the BBC he pronounced: “Anything we can actually do we can afford.” This was followed by political action and in 1945 the UK ushered in the world’s first welfare state.

The immediate post-World War II years were marked by a fundamental shift from the pre-War orthodoxies that had governed public policy in virtually all developed countries of the day. Led by the left, Keynesian pump priming and associated fiscal deficits were no longer off-limit and notions of social justice embodying social safety nets, the public provision of education and health services and public investment in infrastructure took center stage. The intellectual and political battles in favor of giving priority to publicly-funded programs of investment in roads, ports, schools and hospitals and higher social spending, rather than slavishly adhering to a rigid form of fiscal rectitude, the conventional wisdom of the 1920s and 1930s in the developed countries, appeared to have been won.

The UK was governed between 1945 and 1980 on the basis of what came to be known as the Butskellite consensus, named after two prominent politicians of the 1950s, Rab Butler of the Conservative Party and Hugh Gaitskell, Leader of the Labour Party.

But, as it turned out, this acceptance was only a temporary aberration and the ensuing backlash was not long in coming. This was again led by academia in which the UK initially played a minor role but right wing groups, such as think tanks, eagerly jumped on the bandwagon. The ideas of Friedrich Hayek, a pre-war doyen of the right and a member of the Austrian School of Economics, began to appear with greater frequency in books, journals and papers, as did those of Milton Friedman, the father of the similarly right-oriented Chicago School. Both had gained traction in the 1950s with their stress on low inflation and monetary policy. Gradually, their ideas were no longer confined to a right wing fringe, but began to be promoted as not just a viable but a preferable alternative to the pro-welfare consensus that had become current in the UK. Friedman, at first, concentrated his ire on the inflationary pressures that had been allegedly caused by the enlarged role of the state but soon, like Hayek, progressed to become a passionate advocate of free markets, a small state and lower taxes.

The ideology of neoliberalism, also known as market fundamentalism and as the Washington Consensus in the US, was reborn. Political success followed rapidly as the media, now largely in the hands of right wing press barons, attacked the left with renewed confidence and vigour and neoliberalism became mainstream.

Whether or not intentionally, Hayek and Friedman succeeded in conflating two separate issues: one, the post-World War II role of the State in the economy, which involved the creation of a large public sector and the associated regulation of the economy by the State, with two, a more philosophically driven criticism: an alleged restriction on individual freedom that this had supposedly entailed. This was the era of the cold war between the West led by the US and the Soviet bloc led by the USSR. The latter had espoused an entirely different political philosophy in which a more collectivist notion of welfare and of political rights had to be weighed against individual action and individual utility preferences, the former putting greater emphasis on economic rather than political rights.

But, against the powerful US and UK media, the protagonists of the USSR and Eastern Europe could not compete with the blatantly idealized world view, held by the likes of Hayek and Friedman, of individual rights and freedom supposedly available in the US and Western Europe, and of the pursuit of unfettered utility maximization.

This shift in opinion was reflected both in academic circles and in the prevailing political discourse in the UK and, indeed, elsewhere. In both sectors the overall climate of opinion began to move to the right. Thus, the ideology of neoliberalism, also known as market fundamentalism and as the Washington Consensus in the US, was reborn. Political success followed rapidly as the media, now largely in the hands of right wing press barons, attacked the left with renewed confidence and vigour and neoliberalism became mainstream.