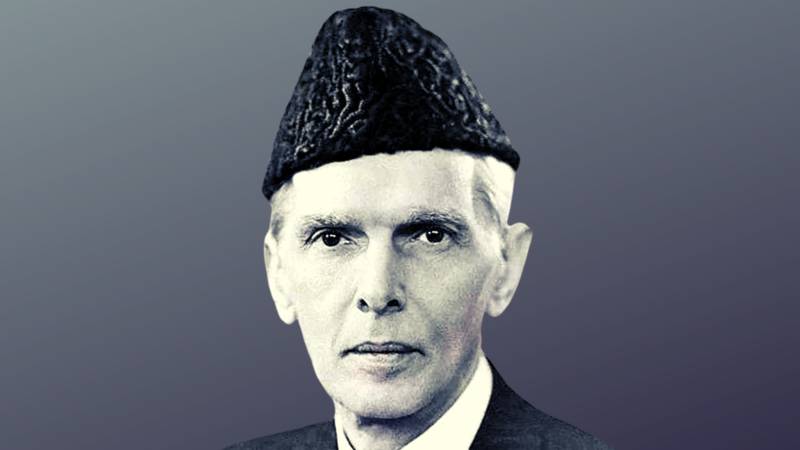

Whenever I walk past the confines of Lincoln’s Inn, the most prestigious Inn to have housed many political geniuses and ardent barristers of the caliber of Muhammad Iqbal, Tony Blair and Z.A. Bhutto, no one comes to my mind more than the founding father of my country—Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who 75 years ago, was eons ahead of his time.

Yet, today’s Pakistan is so far beyond his vision; it is marred by fundamentalism, authoritarianism and political patronage, a state where rule of law is subservient to the will of the ruling elite, where intolerance reigns and today, a state that might or might not be defaulting on its sovereign debt.

At its inception, it was a product of a persistent movement for independence from colonial rule and a bloody political and geographical divorce that uprooted more than 15 million people and resulted in 1 to 2 million dead. Communal violence between Hindu, Muslims and Sikhs, systematic killings, mass plundering, mob thrashings, and organized rapes were part of an unwanted legacy of partition and revealed how deep religious fault lines had become in a society where different communities had coexisted peacefully for centuries.

Many liberals within Pakistan and India since have questioned the efficacy of partition and wondered whether we would have been better off together in a united subcontinent. Others have pointed to the increasingly oppressive state apparatus under Prime Minister Modi’s Hindu nationalist right-wing BJP, where the Muslim minority is actively discriminated against by the state, and Modi’s direct involvement in the 2002 Gujarat riots as Chief Minister of Gujarat that led to the ethnic cleansing of over 2,000 Muslims. However, despite these arguments, only time will tell which camp was right.

Yet, despite the bloody legacy of the partition, Jinnah is revered all over. Stanley Wolpert, commenting on Jinnah’s formidable role in global politics, opined that it is incredibly rare for one man to alter the course of history, rarer still for an individual to modify the map of the world, and hardly anyone can be credited for creating by force of will alone a nation-state and Jinnah remarkably and miraculously did all three. Lord Mountbatten, having enormous confidence in his ability to persuade an audience, felt hopeless when it came to getting Jinnah to agree to anything but what he wanted. In his words, Jinnah had ‘a consuming determination to realize the dream of Pakistan’, one which saw him perish but not stop. In the words of John Biggs-Davison, ‘although without Gandhi, Hindustan would still have gained independence and without Lenin and Mao, Russia and China would still have endured the Communist revolution, without Jinnah, there would have been no Pakistan in 1947.’

Why is it that, 75 years later, Pakistan has conveniently forgotten its formidable architect’s ideology for Pakistan? Jinnah endeavored to create a democratic, egalitarian and secular state where the Muslims of the Indian Subcontinent, who constituted 25% of the population, would not be discriminated against by virtue of their numbers and could enjoy freedoms of religion, speech, expression and political organization. Nowhere did he envision an extremist state that discriminated against minorities and misconstrued religion to advance its own political aims. It is important to understand that while Pakistan was one of the few countries in the world fashioned not on the basis of a common ethnicity, language or nationality, but religion, at the same time, it was not a theocracy.

While religious freedom and political autonomy for the Muslim community was a primary motive for its inception, just like Mandela’s movement against apartheid and self-determination for South Africans, Pakistan was meant to be a republic where everyone had the right to be what they wanted to be. Anything on the contrary was simply not possible, since at the time of partition, there were still two million Hindus who stayed in the country. For years leading up to 1947, Jinnah himself had emphasized the importance of Hindu-Muslim unity. However, despite Congress’s apparently secular rhetoric, he feared that the Muslim minority’s fears of political and social marginalization were not unfounded. In that vein, he endeavored to create a safe haven for them all, where the green in the flag represented the religion of the country’s majority, and the white was a homage to the country’s minorities, thus together a picturesque testimony to light and progress. The prolific Ayesha Jalal has argued that while Jinnah saw Pakistan as a ‘homeland for India’s Muslims,’ it was never meant to be a theocratic state and religion was not to be policed ‘by the guardians of faith.’

Jinnah’s ideology for Pakistan was made clear in a speech when he opined that this state was designed to be the safe haven not just for Muslims but for every citizen as he exclaimed rather passionately: “You are free; you are free to go to your temples. You are free to go to your mosques or to any other places of worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion, caste or creed—that has nothing to do with the business of the state.”

However, 75 years on, how are those representing the white in Pakistan’s emblem fairing today? Today’s Pakistan is held hostage by a plethora of divisive, intersecting fault lines, from sectarian violence against Shia Muslims, over 4,000 of whom have been killed in the past 8 years alone, to the widespread socioeconomic and political persecution of minorities. In 2017 alone, at least 13 Ahmadis were killed and more than 40 wounded; moreover, the Christian minority is actively discriminated against and often fears for its lives, not to mention that Pakistan is in the midst of femicide, where honor killings and gendered and sexual violence are increasingly prevalent. Much of the moral policing, gender-based discrimination and religious persecution of minorities can be attributed to Pakistan’s military dictator Zia-ul-Haq, who vanished as mysteriously as he had arrived, but his systematic imprint on Pakistan’s political institutions, public conscience and societal framework still lives on.

We cannot move forward until we understand why Pakistan came to be; why the nation’s founder emphasized social justice, religious freedom and stressed on safeguarding human rights. It is to be noted that Jinnah’s conception of a secular state was in total consonance with the Islamic ideals of compassion, democratic pluralism and interfaith harmony.

Thus, today it is important more than ever to get out of the confused legacy that was fashioned by political agents to further their own interests and which ate through our institutional and societal framework and transformed us to the intolerant extremist state we are today. Only education can do that. We need to flesh out the extremist rhetoric out of our socio-cultural morass and teach an objective history; a history where Jinnah is a human caricature, not a perfect political idol, a leader who envisioned a secular, progressive and democratic state, where groups and individuals aren’t discriminated against on the basis of their personal beliefs or characteristics. It is the collective responsibility of both the state and political elites to give precedence to democratic institutions over their personal interests for once, to not hamper political processes, to entrench human rights for all in the constitution, to use electoral means to both come to office to do good, and to honor the will of the people once they no longer have popular support. And as individuals, choose compassion and tolerance over hatred every single time. Only then can we realize Jinnah’s Pakistan.

In Jinnah’s words, ‘Pakistan is not going to be a theocratic state - to be ruled by priests with a divine mission. We have many non-Muslims - Hindus, Christians, and Parsis - but they are all Pakistanis. They will enjoy the same rights and privileges as any other citizens and will play their rightful part in the affairs of Pakistan.’

Yet, today’s Pakistan is so far beyond his vision; it is marred by fundamentalism, authoritarianism and political patronage, a state where rule of law is subservient to the will of the ruling elite, where intolerance reigns and today, a state that might or might not be defaulting on its sovereign debt.

At its inception, it was a product of a persistent movement for independence from colonial rule and a bloody political and geographical divorce that uprooted more than 15 million people and resulted in 1 to 2 million dead. Communal violence between Hindu, Muslims and Sikhs, systematic killings, mass plundering, mob thrashings, and organized rapes were part of an unwanted legacy of partition and revealed how deep religious fault lines had become in a society where different communities had coexisted peacefully for centuries.

Many liberals within Pakistan and India since have questioned the efficacy of partition and wondered whether we would have been better off together in a united subcontinent. Others have pointed to the increasingly oppressive state apparatus under Prime Minister Modi’s Hindu nationalist right-wing BJP, where the Muslim minority is actively discriminated against by the state, and Modi’s direct involvement in the 2002 Gujarat riots as Chief Minister of Gujarat that led to the ethnic cleansing of over 2,000 Muslims. However, despite these arguments, only time will tell which camp was right.

Yet, despite the bloody legacy of the partition, Jinnah is revered all over. Stanley Wolpert, commenting on Jinnah’s formidable role in global politics, opined that it is incredibly rare for one man to alter the course of history, rarer still for an individual to modify the map of the world, and hardly anyone can be credited for creating by force of will alone a nation-state and Jinnah remarkably and miraculously did all three. Lord Mountbatten, having enormous confidence in his ability to persuade an audience, felt hopeless when it came to getting Jinnah to agree to anything but what he wanted. In his words, Jinnah had ‘a consuming determination to realize the dream of Pakistan’, one which saw him perish but not stop. In the words of John Biggs-Davison, ‘although without Gandhi, Hindustan would still have gained independence and without Lenin and Mao, Russia and China would still have endured the Communist revolution, without Jinnah, there would have been no Pakistan in 1947.’

Why is it that, 75 years later, Pakistan has conveniently forgotten its formidable architect’s ideology for Pakistan? Jinnah endeavored to create a democratic, egalitarian and secular state where the Muslims of the Indian Subcontinent, who constituted 25% of the population, would not be discriminated against by virtue of their numbers and could enjoy freedoms of religion, speech, expression and political organization. Nowhere did he envision an extremist state that discriminated against minorities and misconstrued religion to advance its own political aims. It is important to understand that while Pakistan was one of the few countries in the world fashioned not on the basis of a common ethnicity, language or nationality, but religion, at the same time, it was not a theocracy.

While religious freedom and political autonomy for the Muslim community was a primary motive for its inception, just like Mandela’s movement against apartheid and self-determination for South Africans, Pakistan was meant to be a republic where everyone had the right to be what they wanted to be. Anything on the contrary was simply not possible, since at the time of partition, there were still two million Hindus who stayed in the country. For years leading up to 1947, Jinnah himself had emphasized the importance of Hindu-Muslim unity. However, despite Congress’s apparently secular rhetoric, he feared that the Muslim minority’s fears of political and social marginalization were not unfounded. In that vein, he endeavored to create a safe haven for them all, where the green in the flag represented the religion of the country’s majority, and the white was a homage to the country’s minorities, thus together a picturesque testimony to light and progress. The prolific Ayesha Jalal has argued that while Jinnah saw Pakistan as a ‘homeland for India’s Muslims,’ it was never meant to be a theocratic state and religion was not to be policed ‘by the guardians of faith.’

Jinnah’s ideology for Pakistan was made clear in a speech when he opined that this state was designed to be the safe haven not just for Muslims but for every citizen as he exclaimed rather passionately: “You are free; you are free to go to your temples. You are free to go to your mosques or to any other places of worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion, caste or creed—that has nothing to do with the business of the state.”

However, 75 years on, how are those representing the white in Pakistan’s emblem fairing today? Today’s Pakistan is held hostage by a plethora of divisive, intersecting fault lines, from sectarian violence against Shia Muslims, over 4,000 of whom have been killed in the past 8 years alone, to the widespread socioeconomic and political persecution of minorities. In 2017 alone, at least 13 Ahmadis were killed and more than 40 wounded; moreover, the Christian minority is actively discriminated against and often fears for its lives, not to mention that Pakistan is in the midst of femicide, where honor killings and gendered and sexual violence are increasingly prevalent. Much of the moral policing, gender-based discrimination and religious persecution of minorities can be attributed to Pakistan’s military dictator Zia-ul-Haq, who vanished as mysteriously as he had arrived, but his systematic imprint on Pakistan’s political institutions, public conscience and societal framework still lives on.

We cannot move forward until we understand why Pakistan came to be; why the nation’s founder emphasized social justice, religious freedom and stressed on safeguarding human rights. It is to be noted that Jinnah’s conception of a secular state was in total consonance with the Islamic ideals of compassion, democratic pluralism and interfaith harmony.

Thus, today it is important more than ever to get out of the confused legacy that was fashioned by political agents to further their own interests and which ate through our institutional and societal framework and transformed us to the intolerant extremist state we are today. Only education can do that. We need to flesh out the extremist rhetoric out of our socio-cultural morass and teach an objective history; a history where Jinnah is a human caricature, not a perfect political idol, a leader who envisioned a secular, progressive and democratic state, where groups and individuals aren’t discriminated against on the basis of their personal beliefs or characteristics. It is the collective responsibility of both the state and political elites to give precedence to democratic institutions over their personal interests for once, to not hamper political processes, to entrench human rights for all in the constitution, to use electoral means to both come to office to do good, and to honor the will of the people once they no longer have popular support. And as individuals, choose compassion and tolerance over hatred every single time. Only then can we realize Jinnah’s Pakistan.

In Jinnah’s words, ‘Pakistan is not going to be a theocratic state - to be ruled by priests with a divine mission. We have many non-Muslims - Hindus, Christians, and Parsis - but they are all Pakistanis. They will enjoy the same rights and privileges as any other citizens and will play their rightful part in the affairs of Pakistan.’