The pyramids at Giza near Cairo are the only surviving members of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. I first visited them in November 1996. They made quite an impact on me. But it was during my second visit several years later that they truly cast a spell on me.

This time I was accompanied by my wife and daughters. We were staying at the Sheraton in Giza, to be as close to the Great Pyramids as possible. The pyramids, we were told, were a short walk away.

The drive from the airport to Giza in a taxi went past some dramatic architectural monuments: forts, mosques and an aqueduct dating back to the times of Salahuddin Ayubi being among them. Of course, the traffic was heavy and unstructured, punctuated by honking sounds. At some point, we passed a dead person who was lying on the side of the road, wrapped in a white shroud, probably a casualty of the chaotic traffic.

And then, out of nowhere, there appeared an apparition over the horizon. It was the Great Pyramid. It seemed to just hang in the air, shivering and simmering in the afternoon sunlight. The desert air co-mixed with automotive exhaust had tinged it with light blue.

As I set eyes on them, a quote from Napoleon stirred in my mind. Addressing his troops in Egypt (21 July 1798), presumably mounted on a white horse, he addressed his troops marshaled in front of the pyramids: “Soldiers, from the summit of yonder pyramids forty centuries look down upon you...”

We checked into the hotel, feasted on our first of many Egyptian dinners, and went to bed. We awoke to the sound of the call to prayer. After breakfast, we prepared ourselves for the walk to the pyramids. But the concierge advised us to hire a tour guide with a van, saying it would be hard to cross the street on foot because of the heavy traffic and the risk of pickpockets. That was indeed the case.

We checked into the hotel, feasted on our first of many Egyptian dinners, and went to bed. We awoke to the sound of the call to prayer. After breakfast, we prepared ourselves for the walk to the pyramids. But the concierge advised us to hire a tour guide with a van, saying it would be hard to cross the street on foot because of the heavy traffic and the risk of pickpockets. That was indeed the case.

Our tour guide was well educated, laughed a lot - which we loved - and spoke fluent English. What more could you ask for? He drove us to the parking lot that stood at the entrance to the pyramids. Colourfully decorated camels with their drivers were seated all around us, and their drivers were waiting to take us for a ride. Our daughters volunteered and proceeded on that tour with our guide.

As they boarded the seated camels, and as the beasts stood up, first on their hind legs and then on their front legs, the usual see-saw movement occurred. The first time is always frightening because your sense of perspective is destroyed. The older daughter yelled and screamed. The camel driver was used to this. He just tapped on her shins and stability was restored. They got to see and experience the pyramids in the old fashioned, genuine way.

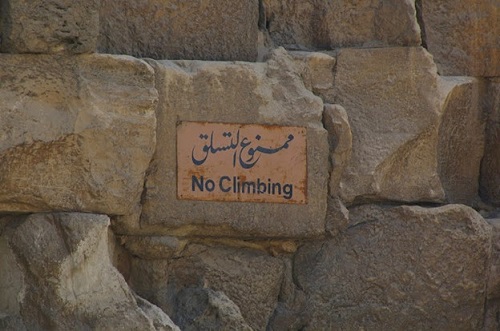

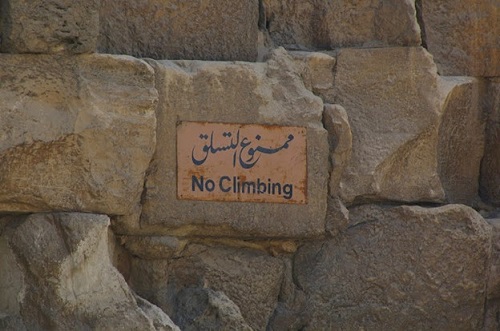

The pyramids dwarfed anything in sight or virtually anything that could be humanly imagined. They were layers and layers of large blocks, each one of which seemed to dwarf the people who were posing near them. Some were climbing the pyramids despite strict admonitions that were posted on signs all around the ancient ruins.

The three-dimensional structures seemed to be the epitome of symmetry. They rested on a sea of sand. And if you looked away from the city from which we had come, the desert stretched out endlessly. It was a scene that evoked David Lean’s film, Lawrence of Arabia.

That film is as much a biopic of the man who liberated the Arab lands from the Ottoman Empire during the period of the Great War, as it is a meditation on the intense sun that blazes on the sands of Arabia. T.E. Lawrence, a colonel of the British army who never attended a military academy, was an archaeologist by training. How he turned into a spy and intelligence officer who would turn into the leader of a guerilla movement and write the ultimate book on the topic is another story.

The pyramids looked desolate, like time had passed them by. There was no sign of the grandeur of the pharaohs. The coffins had long been stolen by tomb robbers. Nothing of any value was to be found in the heart of the pyramids. A narrow passage led to the interior. Tours were offered but I had been told to not go in there unless I wanted to be stricken first by claustrophobia and then a backache. We remained outside and contemplated the monuments.

The silence of the sands and the emptiness of the pyramids spoke volumes. It brought to mind the scene described in the closing verses of Shelly’s poem mind, Ozymandias: “Nothing beside remains. Round the decay/Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare/The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

The September sun shone intensely on the pyramids and heated up the sands all around us. To me and my wife, the best way to see the pyramids was by riding in one of those horse-driven carriages that were lined up nearby. We boarded one of those. The driver, a lively sort, narrated his version of the history of ancient Egypt. I kept sipping on a bottle of 7 Up that I had picked up from one of the stands.

The September sun shone intensely on the pyramids and heated up the sands all around us. To me and my wife, the best way to see the pyramids was by riding in one of those horse-driven carriages that were lined up nearby. We boarded one of those. The driver, a lively sort, narrated his version of the history of ancient Egypt. I kept sipping on a bottle of 7 Up that I had picked up from one of the stands.

After the tour, we reconnected with our daughters. There were the obligatory photo-op moments with the pyramids.

And after that we went to have lunch at a café which had a near-perfect view of the Sphinx. It showed how small the Sphinx was in comparison to the Great Pyramid. Apparently, it was discovered many years later, buried in the sand. It is unclear when it was built. But the damage on the face of the beast was very clear. In Arabic, it is called Abu Al Haul, or the Terrifying One.

In the sweltering heat, I could feel the perspiration from my forehead entering my eyes, turning them salty, and evoking a reflexive movement of the hands toward the eyes, furthering the misery. I asked for a can of ice-cold coke and quenched it.

The Museum of Antiquities

Afterwards, we got into a taxi and went to see the hallowed Egyptian memorabilia in the Museum of Antiquities with the tour guide that we had hired at the hotel.

We entered the museum to find that it was full of tourists from around the globe. I knew enough Russian to understand that most of the tourists were from that country, which had ties with Egypt going back to the post-war Nasser period.

There was no air conditioning. Was it installed? Or was it broken? Those seem to be academic questions. I felt dizzy and wanted to sit down. But there was no place to sit.

I asked the guide if there was an air-conditioned room and explained that I was not feeling well. He took me and my wife to a room that had a few glass caskets containing mummies, which explained the presence of air conditioning. Then he disappeared with my daughters to continue the tour.

In the room, a few tourists were checking out the contents of the caskets with great interest. This was not the room with the mummy of Ramses II. That was a special room that I had seen during my first visit to Egypt. It had a special admittance ticket. We were going to see that once I felt a little better.

My wife and I sat down on a bench, and I felt better but not much better. My eyes spotted an empty glass casket. It was in the middle of the room, just a few feet away from me. My body wanted to enter it and lie horizontal in it for a few minutes with my eyes shut.

There was an irresistible temptation to open the casket, but I knew that was not possible. It was probably locked. And even if it was not locked, there would be a commotion when I opened it. Perhaps an alarm would go off.

But I could not help mentioning the idea to my wife. She knew this was not a sick joke but a serious request from a sick man. She panicked and asked the guard at the entrance to call the medics. They came in a few minutes. I had seen a clinic at the entrance to the museum on the first floor. It had a big white crescent on a red background on the door. I had assumed they would take me there in a stretcher.

But they had come instead with a large hand truck of the type used by UPS for big and heavy parcels. They directed me to step into it. But there was no seat or cushion on the horizontal segment. I hesitated to get in this “industrial” contraption. They picked me up and placed me on the horizontal portion. And then I was wheeled out of the room.

My wife was walking with me. We were now moving through the main hall which was thronged by hordes of tourists on both sides. They had been checking out the ancient collections. But now they all turned their heads to watch this curious procession. I made no eye contact with anyone. I was too ill to smile anyway.

My wife was walking with me. We were now moving through the main hall which was thronged by hordes of tourists on both sides. They had been checking out the ancient collections. But now they all turned their heads to watch this curious procession. I made no eye contact with anyone. I was too ill to smile anyway.

Along the way, our daughters, who had been touring the museum with the guide, became aware of the commotion, spotted me being transported like a pharaoh by three men in uniform and hurried along to join the convoy.

Then we approached the steps we had come up on. I wondered if a lift might be available. But there was none. The medics lifted up the hand truck, in a precarious balancing maneuver, and went down the steps with me “in the saddle,” without any restraint or seat belt.

We approached the clinic at the entrance of the museum. A woman in black robes with her hair totally covered was waiting. They had alerted her. She said that she was the doctor in residence. The first question was if I had diarrhea. I said “no.” I told her about the morning tour of the pyramids and how salty perspiration had entered my eyes.

She asked me to lie down on the bed and took my temperature and blood pressure. The latter was very low. She said, “You are dehydrated and I will give you a saline shot.” Then she asked me to turn to my side and to lower my trousers.

That was awkward because by now my daughters had arrived, along with the guide, and my wife was there as well. And what made it particularly embarrassing was that the doctor was a woman, covered from head to toe in traditional Arab attire.

From the corner of my eye, I saw the big syringe glint in the sunlight that was pouring in from the window. And then I felt the needle.

Ten minutes later the doctor took my blood pressure again. She said that it had returned to normal. “Get up slowly.” I did. “Now walk around the room.” I did. It felt normal. I felt like Lazarus, raised from the dead. My vacation had been returned to me, along with my life.

I thanked the doctor. We left the room, but I no longer had an interest in touring the museum. What I had been through was enough. I just wanted to feel the fresh air. Ramses II would have to wait for a third visit. I was done with the antiquities.

In the days that followed, we toured the Mohammed Ali Mosque. All of Cairo, the city whose name means victorious, lay under its feet. We also toured the Old City and stood at the grave of the Shah of Iran. The King of Kings was not destined to be buried in his own country.

The next day we drove to the seaside town of Alexandria in a taxi. The driver is a little more than two hours long. Along the way, we heard the recitation of the Quran. The driver had put that on.

As we arrived in Alexandria, we saw the blue waters of the Mediterranean. They left us entranced. We visited the beautiful new library, which may have been constructed on the site of the famed old library.

We saw some of the Roman ruins, and searched in vain for the lost harbour of Cleopatra. Both her tomb and Alexander’s tomb have defied archaeologists who have been looking for them for decades.

Then we flew off to the seaside resort of Sharm El-Sheik in the Sinai on Egypt Air for a few days. It was absolutely beautiful with wonderful beaches, restaurants and markets. There was no time, unfortunately, to check out Mt. Sinai. According to tradition, the Ten Commandments were revealed there to Moses. That will have to await a future visit.

This time I was accompanied by my wife and daughters. We were staying at the Sheraton in Giza, to be as close to the Great Pyramids as possible. The pyramids, we were told, were a short walk away.

The drive from the airport to Giza in a taxi went past some dramatic architectural monuments: forts, mosques and an aqueduct dating back to the times of Salahuddin Ayubi being among them. Of course, the traffic was heavy and unstructured, punctuated by honking sounds. At some point, we passed a dead person who was lying on the side of the road, wrapped in a white shroud, probably a casualty of the chaotic traffic.

And then, out of nowhere, there appeared an apparition over the horizon. It was the Great Pyramid. It seemed to just hang in the air, shivering and simmering in the afternoon sunlight. The desert air co-mixed with automotive exhaust had tinged it with light blue.

As I set eyes on them, a quote from Napoleon stirred in my mind. Addressing his troops in Egypt (21 July 1798), presumably mounted on a white horse, he addressed his troops marshaled in front of the pyramids: “Soldiers, from the summit of yonder pyramids forty centuries look down upon you...”

We checked into the hotel, feasted on our first of many Egyptian dinners, and went to bed. We awoke to the sound of the call to prayer. After breakfast, we prepared ourselves for the walk to the pyramids. But the concierge advised us to hire a tour guide with a van, saying it would be hard to cross the street on foot because of the heavy traffic and the risk of pickpockets. That was indeed the case.

We checked into the hotel, feasted on our first of many Egyptian dinners, and went to bed. We awoke to the sound of the call to prayer. After breakfast, we prepared ourselves for the walk to the pyramids. But the concierge advised us to hire a tour guide with a van, saying it would be hard to cross the street on foot because of the heavy traffic and the risk of pickpockets. That was indeed the case.Our tour guide was well educated, laughed a lot - which we loved - and spoke fluent English. What more could you ask for? He drove us to the parking lot that stood at the entrance to the pyramids. Colourfully decorated camels with their drivers were seated all around us, and their drivers were waiting to take us for a ride. Our daughters volunteered and proceeded on that tour with our guide.

As they boarded the seated camels, and as the beasts stood up, first on their hind legs and then on their front legs, the usual see-saw movement occurred. The first time is always frightening because your sense of perspective is destroyed. The older daughter yelled and screamed. The camel driver was used to this. He just tapped on her shins and stability was restored. They got to see and experience the pyramids in the old fashioned, genuine way.

The pyramids dwarfed anything in sight or virtually anything that could be humanly imagined. They were layers and layers of large blocks, each one of which seemed to dwarf the people who were posing near them. Some were climbing the pyramids despite strict admonitions that were posted on signs all around the ancient ruins.

The September sun shone intensely on the pyramids and heated up the sands all around us. To me and my wife, the best way to see the pyramids was by riding in one of those horse-driven carriages that were lined up nearby

The three-dimensional structures seemed to be the epitome of symmetry. They rested on a sea of sand. And if you looked away from the city from which we had come, the desert stretched out endlessly. It was a scene that evoked David Lean’s film, Lawrence of Arabia.

That film is as much a biopic of the man who liberated the Arab lands from the Ottoman Empire during the period of the Great War, as it is a meditation on the intense sun that blazes on the sands of Arabia. T.E. Lawrence, a colonel of the British army who never attended a military academy, was an archaeologist by training. How he turned into a spy and intelligence officer who would turn into the leader of a guerilla movement and write the ultimate book on the topic is another story.

The pyramids looked desolate, like time had passed them by. There was no sign of the grandeur of the pharaohs. The coffins had long been stolen by tomb robbers. Nothing of any value was to be found in the heart of the pyramids. A narrow passage led to the interior. Tours were offered but I had been told to not go in there unless I wanted to be stricken first by claustrophobia and then a backache. We remained outside and contemplated the monuments.

The silence of the sands and the emptiness of the pyramids spoke volumes. It brought to mind the scene described in the closing verses of Shelly’s poem mind, Ozymandias: “Nothing beside remains. Round the decay/Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare/The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

The September sun shone intensely on the pyramids and heated up the sands all around us. To me and my wife, the best way to see the pyramids was by riding in one of those horse-driven carriages that were lined up nearby. We boarded one of those. The driver, a lively sort, narrated his version of the history of ancient Egypt. I kept sipping on a bottle of 7 Up that I had picked up from one of the stands.

The September sun shone intensely on the pyramids and heated up the sands all around us. To me and my wife, the best way to see the pyramids was by riding in one of those horse-driven carriages that were lined up nearby. We boarded one of those. The driver, a lively sort, narrated his version of the history of ancient Egypt. I kept sipping on a bottle of 7 Up that I had picked up from one of the stands.After the tour, we reconnected with our daughters. There were the obligatory photo-op moments with the pyramids.

And after that we went to have lunch at a café which had a near-perfect view of the Sphinx. It showed how small the Sphinx was in comparison to the Great Pyramid. Apparently, it was discovered many years later, buried in the sand. It is unclear when it was built. But the damage on the face of the beast was very clear. In Arabic, it is called Abu Al Haul, or the Terrifying One.

In the sweltering heat, I could feel the perspiration from my forehead entering my eyes, turning them salty, and evoking a reflexive movement of the hands toward the eyes, furthering the misery. I asked for a can of ice-cold coke and quenched it.

The Museum of Antiquities

Afterwards, we got into a taxi and went to see the hallowed Egyptian memorabilia in the Museum of Antiquities with the tour guide that we had hired at the hotel.

We entered the museum to find that it was full of tourists from around the globe. I knew enough Russian to understand that most of the tourists were from that country, which had ties with Egypt going back to the post-war Nasser period.

There was no air conditioning. Was it installed? Or was it broken? Those seem to be academic questions. I felt dizzy and wanted to sit down. But there was no place to sit.

I asked the guide if there was an air-conditioned room and explained that I was not feeling well. He took me and my wife to a room that had a few glass caskets containing mummies, which explained the presence of air conditioning. Then he disappeared with my daughters to continue the tour.

In the room, a few tourists were checking out the contents of the caskets with great interest. This was not the room with the mummy of Ramses II. That was a special room that I had seen during my first visit to Egypt. It had a special admittance ticket. We were going to see that once I felt a little better.

My wife and I sat down on a bench, and I felt better but not much better. My eyes spotted an empty glass casket. It was in the middle of the room, just a few feet away from me. My body wanted to enter it and lie horizontal in it for a few minutes with my eyes shut.

There was an irresistible temptation to open the casket, but I knew that was not possible. It was probably locked. And even if it was not locked, there would be a commotion when I opened it. Perhaps an alarm would go off.

But I could not help mentioning the idea to my wife. She knew this was not a sick joke but a serious request from a sick man. She panicked and asked the guard at the entrance to call the medics. They came in a few minutes. I had seen a clinic at the entrance to the museum on the first floor. It had a big white crescent on a red background on the door. I had assumed they would take me there in a stretcher.

But they had come instead with a large hand truck of the type used by UPS for big and heavy parcels. They directed me to step into it. But there was no seat or cushion on the horizontal segment. I hesitated to get in this “industrial” contraption. They picked me up and placed me on the horizontal portion. And then I was wheeled out of the room.

My wife was walking with me. We were now moving through the main hall which was thronged by hordes of tourists on both sides. They had been checking out the ancient collections. But now they all turned their heads to watch this curious procession. I made no eye contact with anyone. I was too ill to smile anyway.

My wife was walking with me. We were now moving through the main hall which was thronged by hordes of tourists on both sides. They had been checking out the ancient collections. But now they all turned their heads to watch this curious procession. I made no eye contact with anyone. I was too ill to smile anyway.Along the way, our daughters, who had been touring the museum with the guide, became aware of the commotion, spotted me being transported like a pharaoh by three men in uniform and hurried along to join the convoy.

Then we approached the steps we had come up on. I wondered if a lift might be available. But there was none. The medics lifted up the hand truck, in a precarious balancing maneuver, and went down the steps with me “in the saddle,” without any restraint or seat belt.

We approached the clinic at the entrance of the museum. A woman in black robes with her hair totally covered was waiting. They had alerted her. She said that she was the doctor in residence. The first question was if I had diarrhea. I said “no.” I told her about the morning tour of the pyramids and how salty perspiration had entered my eyes.

She asked me to lie down on the bed and took my temperature and blood pressure. The latter was very low. She said, “You are dehydrated and I will give you a saline shot.” Then she asked me to turn to my side and to lower my trousers.

That was awkward because by now my daughters had arrived, along with the guide, and my wife was there as well. And what made it particularly embarrassing was that the doctor was a woman, covered from head to toe in traditional Arab attire.

From the corner of my eye, I saw the big syringe glint in the sunlight that was pouring in from the window. And then I felt the needle.

Ten minutes later the doctor took my blood pressure again. She said that it had returned to normal. “Get up slowly.” I did. “Now walk around the room.” I did. It felt normal. I felt like Lazarus, raised from the dead. My vacation had been returned to me, along with my life.

I thanked the doctor. We left the room, but I no longer had an interest in touring the museum. What I had been through was enough. I just wanted to feel the fresh air. Ramses II would have to wait for a third visit. I was done with the antiquities.

In the days that followed, we toured the Mohammed Ali Mosque. All of Cairo, the city whose name means victorious, lay under its feet. We also toured the Old City and stood at the grave of the Shah of Iran. The King of Kings was not destined to be buried in his own country.

The next day we drove to the seaside town of Alexandria in a taxi. The driver is a little more than two hours long. Along the way, we heard the recitation of the Quran. The driver had put that on.

As we arrived in Alexandria, we saw the blue waters of the Mediterranean. They left us entranced. We visited the beautiful new library, which may have been constructed on the site of the famed old library.

We saw some of the Roman ruins, and searched in vain for the lost harbour of Cleopatra. Both her tomb and Alexander’s tomb have defied archaeologists who have been looking for them for decades.

Then we flew off to the seaside resort of Sharm El-Sheik in the Sinai on Egypt Air for a few days. It was absolutely beautiful with wonderful beaches, restaurants and markets. There was no time, unfortunately, to check out Mt. Sinai. According to tradition, the Ten Commandments were revealed there to Moses. That will have to await a future visit.