We hear the word ‘democracy’ a lot in Pakistan. We hear it from politicians, from their supporters and in the media. In discussions and debates, the need to protect democracy and democratic institutions is continuously advocated. Yet, no one is willing to talk about even the simple prerequisites that a society needs to ensure if it is to become truly democratic.

Indeed, there have always been laments about the fragile nature of democracy in Pakistan. But even during all the talk about strengthening it, the perquisites are ignored. Most perquisites are uncomfortable to talk about and thus, just not discussed. Also, quite a few people are simply ignorant about the perquisites. Without these, democracy is likely to remain weak, or worse, won’t be able to exist at all.

So what are the prerequisites?

Let’s begin with the need of having a secular polity. A country that has a state religion and a constitution — many of whose articles and clauses are shaped by theological considerations — will always struggle to become truly democratic. In 18th-century Europe, Christian theologies began being seen as hindrances on the path of democratisation because within these theologies there was nothing that could encourage the establishment of democracy.

Let’s begin with the need of having a secular polity. A country that has a state religion and a constitution — many of whose articles and clauses are shaped by theological considerations — will always struggle to become truly democratic. In 18th-century Europe, Christian theologies began being seen as hindrances on the path of democratisation because within these theologies there was nothing that could encourage the establishment of democracy.

So European nation-states began to secularise their polities and relegate religion to the private sphere. What’s more, even Christianity began to do the same. The many ‘Christian democratic’ parties in Europe today have their roots in this exercise. Unlike the Islamic political parties, or for that matter, Hindu nationalist parties, the mainstream Christian parties in Europe are not in anyway theological. They treat Christianity as part of Europe’s heritage, but beyond that they are entirely secular. They are the outcome of European Christianity’s willingness to operate within the larger secular paradigm.

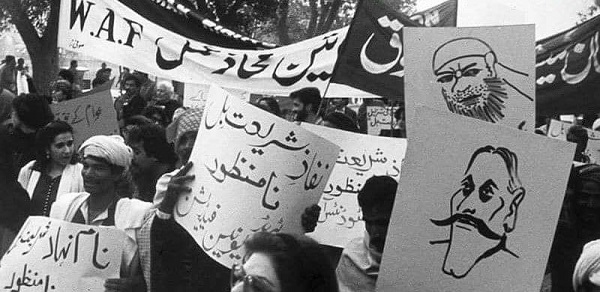

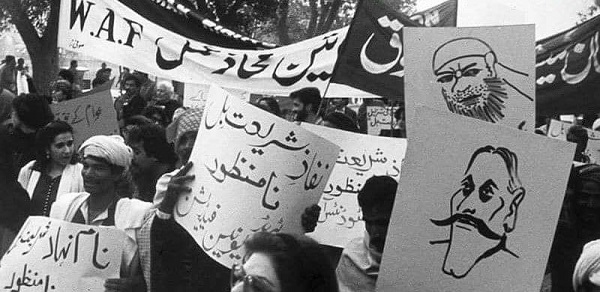

Pakistan, with a thoroughly ‘Islamised’ constitution, is a ‘Constitutional Theocracy.’ Or a ‘Theo-democracy.’ So is Iran, even though its variant is more intense than that of Pakistan. There is a lot of talk about democracy in Pakistan, but none on secularism. All versions of secularism allow the freedom of worship, as long as this freedom is not used for political or legislative purposes. In Pakistan and Iran, there is an insistence of worship which doesn’t bode well with the freedom of worship.

Secondly, Pakistan has a state religion and its constitution does not allow a non-Muslim to become head of State or government. Thirdly, the constitution has empowered legislators to define what a ‘good, pious’ Muslim is and who is not (Articles 62 and 63); who is a Muslim and who is not (2nd Amendment); and what and who is a blasphemer. Basically, when those who speak passionately about strengthening democracy in Pakistan are actually talking about strengthening what is really a Constitutional Theocracy.

Pluralism is another prerequisite. There is enough in Pakistan in the shape of various political parties with their own ideologies and programs. Yet, due to the constitution, any ideology or programme that contradicts or challenges the country’s Constitutional Theocracy will not be able to fully operate. They can become victims of state indifference or attacked by the religious and sectarian majority groups who remain to be the core beneficiaries of the constitution.

Having a robust middle-class is also a prerequisite to having a strong democratic system. Historically, the middle-classes formulated democracy to find a place for themselves in systems that were dominated by royal and landed elites and the clergy. Below were vast swaths of peasants being exploited by the elites. Through democracy, the emerging middle-classes in Europe tried to mediate between the elites and the exploited. And once the power of the elites was neutralised, democracy became a consensual exercise between the middle-classes and the working-classes (the proletariat).

There must be a consensus between all segments of the society that democracy has to be the governing system, no matter which individual or party comes to power. However, sometimes the middle-classes break away from this consensus after feeling threatened by the increasing political influence of the proletariat. This happened in Europe between the two World Wars, consequently giving birth to fascist regimes. In Pakistan, the middle-classes, even though they now constitute approximately 38% of the population, are still not completely satisfied that democracy should be the primary governing system in the country.

The Pakistani middle-classes have a history of aiding and supporting military regimes and demonising democratic parties. Even when the middle-classes managed to erect a significant party of their own, as happened during the rise of Imran Khan’s PTI, the desire still was to mould an authoritarian leader with the power to manoeuvre government resources to construct a one-party-state.

Democracy will struggle to fully take root in Pakistan if the country’s middle-classes remain contemptuous of a system that does not guarantee the coming to power of their favourite person, or a system that is not just about them.

Democracy will struggle to fully take root in Pakistan if the country’s middle-classes remain contemptuous of a system that does not guarantee the coming to power of their favourite person, or a system that is not just about them.

So the basic perquisites to building a democracy are secularism, pluralism, and a politically robust middle-class strengthening a democratic system through a consensual engagement with the classes below and above. But what kind of a strong democratic system? As mentioned, Pakistan is a Constitutional Theocracy.

During the first three decades of the country, various Pakistani scholars and intellectuals tried to to build models of ‘Islamic democracy.’ To those on the left, Islam was inherently progressive and democratic and therefore compatible with the modern Westminster school of democracy. This was their way of justifying the coinage of the term ‘Islamic Republic of Pakistan.’

To those on the right, the 7th-century Islamic caliphs (the ‘rightly guided caliphs’) were exercising a form of democracy with which they built an ‘Islamic State.’ Therefore, to advocates of Islamic democracy on the right-wing side, the examples of the caliphs and Islamic scriptures should be the blueprints from which an ‘Islamic Republic’ must be constructed, with a constitution whose main purpose must be to enact a Islamic State ruled by pious men and navigated by Shariah laws.

The problem in both cases, left or right, is not religion, but the politicisation of religion. Both narratives require religion to play a major political role which is not very conducive to democracy. Such a role undermines various universal freedoms that democracy promises. Instead, the idea of freedom in a constitution woven from theological compulsions is based on a single faith or sectarian leaning. Secondly, both the narratives are based on myths and traditions and not on history as such. A majority of Pakistanis, including the democrats, are never quite able to comprehend the difference between traditions built on accounts of hearsay, and history constructed through written and archaeological evidence.

As our democrats continue investing so much effort in talking about democracy, they should be discussing its prerequisites first. They may think they are against dictatorship, but in actuality, they are unwittingly trying to strengthen a Constitutional Theocracy that just doesn’t sit well with Westminster democracy. In fact, it can become as problematic as a dictatorship, or worse, a system in which acts of bigotry and non-inclusiveness are enshrined in the constitution.

Indeed, there have always been laments about the fragile nature of democracy in Pakistan. But even during all the talk about strengthening it, the perquisites are ignored. Most perquisites are uncomfortable to talk about and thus, just not discussed. Also, quite a few people are simply ignorant about the perquisites. Without these, democracy is likely to remain weak, or worse, won’t be able to exist at all.

So what are the prerequisites?

Let’s begin with the need of having a secular polity. A country that has a state religion and a constitution — many of whose articles and clauses are shaped by theological considerations — will always struggle to become truly democratic. In 18th-century Europe, Christian theologies began being seen as hindrances on the path of democratisation because within these theologies there was nothing that could encourage the establishment of democracy.

Let’s begin with the need of having a secular polity. A country that has a state religion and a constitution — many of whose articles and clauses are shaped by theological considerations — will always struggle to become truly democratic. In 18th-century Europe, Christian theologies began being seen as hindrances on the path of democratisation because within these theologies there was nothing that could encourage the establishment of democracy.So European nation-states began to secularise their polities and relegate religion to the private sphere. What’s more, even Christianity began to do the same. The many ‘Christian democratic’ parties in Europe today have their roots in this exercise. Unlike the Islamic political parties, or for that matter, Hindu nationalist parties, the mainstream Christian parties in Europe are not in anyway theological. They treat Christianity as part of Europe’s heritage, but beyond that they are entirely secular. They are the outcome of European Christianity’s willingness to operate within the larger secular paradigm.

Pakistan, with a thoroughly ‘Islamised’ constitution, is a ‘Constitutional Theocracy.’ Or a ‘Theo-democracy.’ So is Iran, even though its variant is more intense than that of Pakistan. There is a lot of talk about democracy in Pakistan, but none on secularism. All versions of secularism allow the freedom of worship, as long as this freedom is not used for political or legislative purposes. In Pakistan and Iran, there is an insistence of worship which doesn’t bode well with the freedom of worship.

The problem in both cases, left or right, is not religion, but the politicisation of religion. Both narratives require religion to play a major political role which is not very conducive to democracy. Such a role undermines various universal freedoms that democracy promises

Secondly, Pakistan has a state religion and its constitution does not allow a non-Muslim to become head of State or government. Thirdly, the constitution has empowered legislators to define what a ‘good, pious’ Muslim is and who is not (Articles 62 and 63); who is a Muslim and who is not (2nd Amendment); and what and who is a blasphemer. Basically, when those who speak passionately about strengthening democracy in Pakistan are actually talking about strengthening what is really a Constitutional Theocracy.

Pluralism is another prerequisite. There is enough in Pakistan in the shape of various political parties with their own ideologies and programs. Yet, due to the constitution, any ideology or programme that contradicts or challenges the country’s Constitutional Theocracy will not be able to fully operate. They can become victims of state indifference or attacked by the religious and sectarian majority groups who remain to be the core beneficiaries of the constitution.

Having a robust middle-class is also a prerequisite to having a strong democratic system. Historically, the middle-classes formulated democracy to find a place for themselves in systems that were dominated by royal and landed elites and the clergy. Below were vast swaths of peasants being exploited by the elites. Through democracy, the emerging middle-classes in Europe tried to mediate between the elites and the exploited. And once the power of the elites was neutralised, democracy became a consensual exercise between the middle-classes and the working-classes (the proletariat).

There must be a consensus between all segments of the society that democracy has to be the governing system, no matter which individual or party comes to power. However, sometimes the middle-classes break away from this consensus after feeling threatened by the increasing political influence of the proletariat. This happened in Europe between the two World Wars, consequently giving birth to fascist regimes. In Pakistan, the middle-classes, even though they now constitute approximately 38% of the population, are still not completely satisfied that democracy should be the primary governing system in the country.

The Pakistani middle-classes have a history of aiding and supporting military regimes and demonising democratic parties. Even when the middle-classes managed to erect a significant party of their own, as happened during the rise of Imran Khan’s PTI, the desire still was to mould an authoritarian leader with the power to manoeuvre government resources to construct a one-party-state.

Democracy will struggle to fully take root in Pakistan if the country’s middle-classes remain contemptuous of a system that does not guarantee the coming to power of their favourite person, or a system that is not just about them.

Democracy will struggle to fully take root in Pakistan if the country’s middle-classes remain contemptuous of a system that does not guarantee the coming to power of their favourite person, or a system that is not just about them.So the basic perquisites to building a democracy are secularism, pluralism, and a politically robust middle-class strengthening a democratic system through a consensual engagement with the classes below and above. But what kind of a strong democratic system? As mentioned, Pakistan is a Constitutional Theocracy.

During the first three decades of the country, various Pakistani scholars and intellectuals tried to to build models of ‘Islamic democracy.’ To those on the left, Islam was inherently progressive and democratic and therefore compatible with the modern Westminster school of democracy. This was their way of justifying the coinage of the term ‘Islamic Republic of Pakistan.’

To those on the right, the 7th-century Islamic caliphs (the ‘rightly guided caliphs’) were exercising a form of democracy with which they built an ‘Islamic State.’ Therefore, to advocates of Islamic democracy on the right-wing side, the examples of the caliphs and Islamic scriptures should be the blueprints from which an ‘Islamic Republic’ must be constructed, with a constitution whose main purpose must be to enact a Islamic State ruled by pious men and navigated by Shariah laws.

The problem in both cases, left or right, is not religion, but the politicisation of religion. Both narratives require religion to play a major political role which is not very conducive to democracy. Such a role undermines various universal freedoms that democracy promises. Instead, the idea of freedom in a constitution woven from theological compulsions is based on a single faith or sectarian leaning. Secondly, both the narratives are based on myths and traditions and not on history as such. A majority of Pakistanis, including the democrats, are never quite able to comprehend the difference between traditions built on accounts of hearsay, and history constructed through written and archaeological evidence.

As our democrats continue investing so much effort in talking about democracy, they should be discussing its prerequisites first. They may think they are against dictatorship, but in actuality, they are unwittingly trying to strengthen a Constitutional Theocracy that just doesn’t sit well with Westminster democracy. In fact, it can become as problematic as a dictatorship, or worse, a system in which acts of bigotry and non-inclusiveness are enshrined in the constitution.