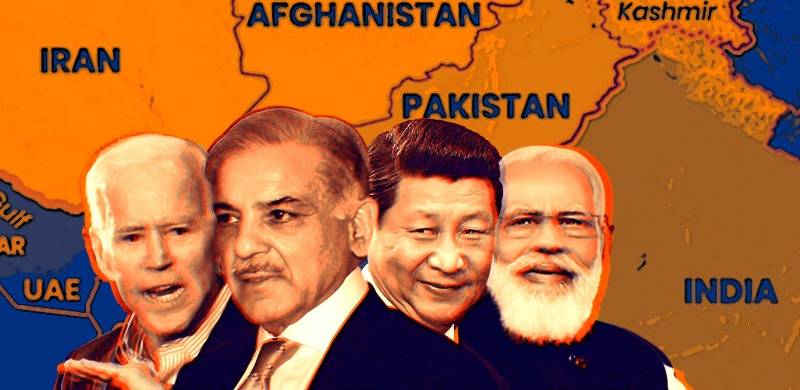

At the domestic level, Pakistan faces two main challenges on the Eastern and Western borders, from India and Afghanistan respectively. The nature of the conflict is based on past animosity and territorial historical claims; Pakistan claims Kashmir on the basis of its Muslim majority population, whereas Afghanistan is not ready to accept the validity of Durand Line agreement. Unfortunately, Pakistan has inherited an extremely challenging environment on both of its borders, which have burdened and hampered the progress of the state since its inception in 1947.

On the eastern border, Pakistan is under direct pressure from Indian predatory intentions; India is not a regional hegemon just yet, but it is abundantly clear that it possesses hegemonic designs to dominate the South Asian region. However, the geopolitical position of Pakistan and the Kashmir conflict have exerted immense pressure on Pakistan’s foreign policy measures from the very beginning.

India and Pakistan both are caught in a spiral of insecurities and a perennial trust deficit, which has never allowed the region to breath and connect peacefully. The security dilemma has affected Pakistan more than India: first, it is the main reason behind the heavy armed buildup, nuclearization and the overdeveloped military apparatus of the state. Secondly, it has made Pakistan ‘India-centric’ and it has dictated our all policies towards our neighbors and other major powers. Worst of all, it has not let Pakistan prioritize its other sociopolitical and economic needs and basic requirements.

The other mounting challenge is on the western border of Pakistan. Afghanistan has never had harmonious relationships with Pakistan, except in the 1990s during the first phase of the Taliban regime, for which Pakistan paid a heavy price. Pakistan’s policy towards Afghanistan backfired after the Soviet-Afghan invasion and the ascendence of the Taliban to power. It was a complete failure under the aegis of ‘strategic depth.’ For Pakistan, it was a short-lived perception but for Afghanistan, the memories of the era have lingered in their memories. The second disastrous step was Pakistan’s role as a key frontline ally in the War on Terror, which turned the Afghan nation against Pakistan. It also strengthened Indian footholds in Afghanistan and led to both due and undue measures being used to destabilize Pakistan internally. The Delhi-Kabul nexus left Pakistan in a nut cracker situation, strategically encircled by Indian influence. Nonetheless, things have changed after the US withdrawal, but it gave rise to other challenges as TTP and other Indian supported groups operating against Pakistan. Currently, Pakistan is more cautious towards the Taliban government in Afghanistan, and its strategy is more along the lines of ‘wait and see’ for longer durability and nonviolent coexistence.

At the regional level, Pakistan had a fluctuating relationship with Iran, though Iran strategically is very important to Pakistan. Pakistan’s policy measures towards Iran have been dominated with the Saudi Arabia element, and its hostile relationship and ideological clash with Iran, which has never really allowed Pakistan to maintain a relationship with Iran on its own terms. Saudi Arabia has been an old reliable ally, financial supporter and a host to millions of Pakistani laborers. Consequently, Pakistan could never materialize the potential energy resources via Iran and other trade viability due to Saudi Arabia’s mounting concerns and US pressure after the Iranian revolution. The reality is that economically dependent countries are bound to take dictations from their financial supporters.

Since 1962 and the Sino-Indian war, Pakistan has observed a good and trustable relationship with China. It’s a strategic need for China to have a good relationship with Pakistan and vice versa, to counter India in the region and to stretch its economic ventures. Pakistan-China relations are diverse in nature, in terms of security, weaponization, economy, trade and people to people contact. Pakistan has heavily relied on China despite of the severe socio-cultural and language differences between both states. Similarly, China has always supported Pakistan in its tough times. The second prominent project is CPEC - the flagship route of the Belt and Road Initiative, which appeared as one of the major concerns and threat for India and for the Western world. Pakistan was lucky enough to be part of this project and for the first time its strategic location will be materialized on economic terms. However, under the current set of circumstances, the project is passing through a set of severe implementation challenges from the Pakistani side, which need to be dealt with more serious effort for future ventures.

Moreover, Pakistan-Russia relations have been limited, since 1947 Pakistan has been in the US orbit, whereas India was in support of the Soviet Union, despite Nehru’s Non-Aligned Movement. During the Soviet-Afghan invasion, India supported the Soviets, and Pakistan fought with US weapons and Saudi Arabia’s finances to push the Soviets out of Afghanistan. In the status quo, after the end of the Cold War, Russia is again rising under Putin’s vison and strategy, and looking for Asian allies. On the other hand, for the US, India remains the first option to counter China’s CPEC and Russia’s growing power in Asia. Whereas Pakistan, guided by a more rational approach, is trying to maintain the balance between both poles, to secure stability between both states.

Globally, Pakistan has always been aspiring for US support for survival and to counter the towering Indian threat in the region. Though both states have never been on good terms, their relationship has always been more of a client and master relationship. The US has always left Pakistan in the lurch after their interests were fulfilled, and Pakistan has every time negotiated with its full capacity to secure the most that they could out of US interests. However, Pakistan has gained very little, and paid a heavy price because of this relationship, whereas the US maintained a policy of de-hyphenation in the South Asian region. Under this policy, US relations with Pakistan and India are to be carried out by an objective assessment of its interests towards each state, keeping in view their merits and de-merits. They used India and Pakistan according to their own interest-oriented policies, and secondly, the US never aspired for a peaceful solution or mediated between both hostile states to balance its influence and interest in the region. History reveals extremely uneven relations between the US and Pakistan, despite their common ventures in Afghanistan and long terms alliances against terrorism.

Thus, Pakistan’s foreign policy dimensions have been extremely challenging and dynamic, coupled with a fragile political system and a frail economy. Though such circumstances are common in many other states, our fault is that we have always looked outside for help and support against our mounting concerns.

It is our fault that we never tried to meet our ends meet within the resources available, knowing that Pakistan has the potential to support its survival and guarantee some measure of prosperity to its people. Secondly, we have always paid more attention to India than it was needed; Pakistan has sustained itself despite all odds and proven its presence and strategic importance among global powers.

Another question which needs to be pondered is that it is fairly certain that no one can wound us from the outside, it is our internal issues which pose a more serious challenge for Pakistan’s stability. Today, our comprehensive security concerns are more worrying than our traditional security apprehensions. It is the need of the hour to look inwards, and provide more control and balance to our internal dimensions and requirements.

On the eastern border, Pakistan is under direct pressure from Indian predatory intentions; India is not a regional hegemon just yet, but it is abundantly clear that it possesses hegemonic designs to dominate the South Asian region. However, the geopolitical position of Pakistan and the Kashmir conflict have exerted immense pressure on Pakistan’s foreign policy measures from the very beginning.

India and Pakistan both are caught in a spiral of insecurities and a perennial trust deficit, which has never allowed the region to breath and connect peacefully. The security dilemma has affected Pakistan more than India: first, it is the main reason behind the heavy armed buildup, nuclearization and the overdeveloped military apparatus of the state. Secondly, it has made Pakistan ‘India-centric’ and it has dictated our all policies towards our neighbors and other major powers. Worst of all, it has not let Pakistan prioritize its other sociopolitical and economic needs and basic requirements.

The other mounting challenge is on the western border of Pakistan. Afghanistan has never had harmonious relationships with Pakistan, except in the 1990s during the first phase of the Taliban regime, for which Pakistan paid a heavy price. Pakistan’s policy towards Afghanistan backfired after the Soviet-Afghan invasion and the ascendence of the Taliban to power. It was a complete failure under the aegis of ‘strategic depth.’ For Pakistan, it was a short-lived perception but for Afghanistan, the memories of the era have lingered in their memories. The second disastrous step was Pakistan’s role as a key frontline ally in the War on Terror, which turned the Afghan nation against Pakistan. It also strengthened Indian footholds in Afghanistan and led to both due and undue measures being used to destabilize Pakistan internally. The Delhi-Kabul nexus left Pakistan in a nut cracker situation, strategically encircled by Indian influence. Nonetheless, things have changed after the US withdrawal, but it gave rise to other challenges as TTP and other Indian supported groups operating against Pakistan. Currently, Pakistan is more cautious towards the Taliban government in Afghanistan, and its strategy is more along the lines of ‘wait and see’ for longer durability and nonviolent coexistence.

At the regional level, Pakistan had a fluctuating relationship with Iran, though Iran strategically is very important to Pakistan. Pakistan’s policy measures towards Iran have been dominated with the Saudi Arabia element, and its hostile relationship and ideological clash with Iran, which has never really allowed Pakistan to maintain a relationship with Iran on its own terms. Saudi Arabia has been an old reliable ally, financial supporter and a host to millions of Pakistani laborers. Consequently, Pakistan could never materialize the potential energy resources via Iran and other trade viability due to Saudi Arabia’s mounting concerns and US pressure after the Iranian revolution. The reality is that economically dependent countries are bound to take dictations from their financial supporters.

Since 1962 and the Sino-Indian war, Pakistan has observed a good and trustable relationship with China. It’s a strategic need for China to have a good relationship with Pakistan and vice versa, to counter India in the region and to stretch its economic ventures. Pakistan-China relations are diverse in nature, in terms of security, weaponization, economy, trade and people to people contact. Pakistan has heavily relied on China despite of the severe socio-cultural and language differences between both states. Similarly, China has always supported Pakistan in its tough times. The second prominent project is CPEC - the flagship route of the Belt and Road Initiative, which appeared as one of the major concerns and threat for India and for the Western world. Pakistan was lucky enough to be part of this project and for the first time its strategic location will be materialized on economic terms. However, under the current set of circumstances, the project is passing through a set of severe implementation challenges from the Pakistani side, which need to be dealt with more serious effort for future ventures.

Moreover, Pakistan-Russia relations have been limited, since 1947 Pakistan has been in the US orbit, whereas India was in support of the Soviet Union, despite Nehru’s Non-Aligned Movement. During the Soviet-Afghan invasion, India supported the Soviets, and Pakistan fought with US weapons and Saudi Arabia’s finances to push the Soviets out of Afghanistan. In the status quo, after the end of the Cold War, Russia is again rising under Putin’s vison and strategy, and looking for Asian allies. On the other hand, for the US, India remains the first option to counter China’s CPEC and Russia’s growing power in Asia. Whereas Pakistan, guided by a more rational approach, is trying to maintain the balance between both poles, to secure stability between both states.

Globally, Pakistan has always been aspiring for US support for survival and to counter the towering Indian threat in the region. Though both states have never been on good terms, their relationship has always been more of a client and master relationship. The US has always left Pakistan in the lurch after their interests were fulfilled, and Pakistan has every time negotiated with its full capacity to secure the most that they could out of US interests. However, Pakistan has gained very little, and paid a heavy price because of this relationship, whereas the US maintained a policy of de-hyphenation in the South Asian region. Under this policy, US relations with Pakistan and India are to be carried out by an objective assessment of its interests towards each state, keeping in view their merits and de-merits. They used India and Pakistan according to their own interest-oriented policies, and secondly, the US never aspired for a peaceful solution or mediated between both hostile states to balance its influence and interest in the region. History reveals extremely uneven relations between the US and Pakistan, despite their common ventures in Afghanistan and long terms alliances against terrorism.

Thus, Pakistan’s foreign policy dimensions have been extremely challenging and dynamic, coupled with a fragile political system and a frail economy. Though such circumstances are common in many other states, our fault is that we have always looked outside for help and support against our mounting concerns.

It is our fault that we never tried to meet our ends meet within the resources available, knowing that Pakistan has the potential to support its survival and guarantee some measure of prosperity to its people. Secondly, we have always paid more attention to India than it was needed; Pakistan has sustained itself despite all odds and proven its presence and strategic importance among global powers.

Another question which needs to be pondered is that it is fairly certain that no one can wound us from the outside, it is our internal issues which pose a more serious challenge for Pakistan’s stability. Today, our comprehensive security concerns are more worrying than our traditional security apprehensions. It is the need of the hour to look inwards, and provide more control and balance to our internal dimensions and requirements.