Imagining the past is no mean feat. Especially if it is the remote past. Even more so if it is a remote past that is less well preserved by peculiar climatic conditions than others. Or if it was less fortunate in escaping decimation from marauders and colonists. If the language of that bygone epoch remains one of the great enigmas of modern archaeology, linguistics and ancient history, then there is even more of a risk that anyone writing about it will be making the cardinal error of projecting her own imaginings of history or the lived reality of the present onto the ancient past. Therefore, any conscientious and rigorous writer of historical fiction makes every endeavour to be both well familiar with all extant serious research on the era, and to also consciously ensure that she doesn't get carried away and write something out of character with our scholarly understandings of the time.

The year 2023 so far has been a good one for Urdu fiction in general and Urdu historical fiction in particular. Sahiwal-based Urdu scholar, academic and writer Hina Jamshed has penned a novel called Hariyupiya, published by Book Corner Jhelum, that I have just finished reading. Veteran writer Tahira Iqbal has also published a new novel called Harappa, published by the same publisher, that I have just started reading. Having focused in one of the six eras of my own novel Snuffing Out the Moon (translated as Chand Ko Gul Karen to Hum Janen) on the Indus Valley Civilisation, I was and am particularly intrigued to discover how these two novelists have envisioned and depicted Harappa and its civilisation.

Three things stood out for me as great positives in Hina Jamshed's novel.

The first - essential for all good historical fiction - is her research. Living in close proximity to the site of the glorious ancient city, she appears to have dug deep into archives, secondary literature and relevant available texts and materials. This not only lends invaluable authenticity to what she writes - as can be easily discerned by someone who is familiar with the scholarly literature - but also appreciable texture, detailing and heft to her descriptions.

While research is an essential ingredient, imagination is equally, if not more, important. Because with limited historical understanding of the place and the era, it is imagination that must fill multiple gaps. This is the second aspect that I wish to highlight. It is apparent that Hina Jamshed has roamed frequently in the silent, mysterious streets of the ancient city, breathing in its atmosphere, listening to leftover whispers from bygone times, and sniffing the fragrance of bygone days. No wonder her storytelling is evocative.

Thirdly I wish to emphasise that for historical fiction it is very important to try hard and imagine things as they actually could have been, as opposed to how one wants them or would like them to be. Here too the novelist puts forth something that is compelling and persuasive. It is an imagined Harappa that is more likely to have existed than not. This I must stress is quite an achievement as there are so many places where the writer can falter while writing a historical novel.

I am not one for writing reviews that paraphrase stories and give away the plot. But in brief, the narrative revolves around two friends Abhaya and Baasa, who are craftsmen of beads and pottery (Jamshed goes into exquisite details of the arts and crafts of the time) who travel to Harappa from the much smaller Indus Valley Civilisation community of Kalibangan in Rajasthan. Accompanying them are Baasa’s daughter - young, charming and pretty girl Gaika - his young son, a child referred to as Balak Komail. Harappa looms gloriously on the horizon at the end of their long journey as the boatman old Sudhewa leads them to it. Grand, well-organised, prudently governed, aesthetic and overwhelming. The city’s high priest, as it turns out, is benevolent and wise. There are black sheep amongst the defenders of the city but on the whole the place is a well-oiled, thrumming engine of trade, commerce, culture and the arts. Yearly floods pose the major threat to it. Else the city thrives and has trade tentacles that extend far and wide to Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, China, Greece, Rome, various Indus Valley Civilisation cities, as well as many other distant lands.

As the novel progresses, tragedy strikes, a question of justice arises, new and interesting characters appear on the scene, romance stirs, and the story crescendos towards a finale where multiple threats of a deluge, administrative breakdown and aggressive mountain people threaten the main characters and their friends as well as the very survival of the city. The plot is believable, and the characters attract one's curiosity and empathy. The main story and characters are well supplemented by side stories and characters and there is no great predictability to the events, which keeps the reader engaged.

While there are interesting and instructive conversations that I look forward to having with the author, I found Hariyupiya to be a well-constructed and richly imagined novel. What will naturally continue to be matters of scholarly and speculative debate are questions such as: were the Harappans actually ruled by a priest caste, as this novel imagines? What was the level of development of their script? How far did their trade extend? What was their language like - a distinct Dravidian script or something that had a vocabulary that later contributed majorly to the Sanskrit of the invaders (this novel's language is very much Sanskrit based and inspired)? There is much to mull over, especially by us historical fiction writers. Tahira Iqbal's novel is bound to deepen this conversation further and add additional perspective and insight.

I must mention here Hina Jamshed's lyrical prose and an overall sense of deep romance that imbues her narrative. The descriptions and imagery are quite charming. The chapters are short and preceded by a brief saying or sentence fragment as a title that is almost always metaphysical and poetic and sets the tone and mood for what is to follow. Hina Jamshed displays great skill: both as a controller of the plot and characterisation, as well as in terms of her facility with consistently using a language that she fashions to suit an era in the ancient past. While the remote past shall probably always not be fully knowable, Hariyupiya offers a depiction that resonates at multiple levels due to what we know so far about the Harappan civilisation. It is also a past which despite its low points and crises, one would like to imagine for Harappa. A past of great sophistication, organisation and amity, that offers lessons even today in terms of harmonious urban existence.

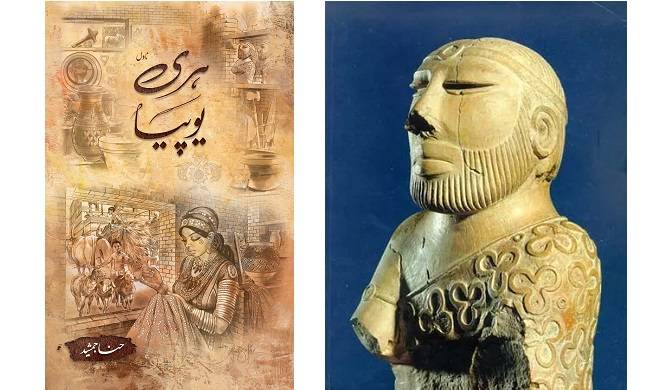

Brothers Amar and Gagan of Book Corner, like the Brothers Karamazov or the Brothers Grimm, always maintain high standards. Well printed and published, with a striking cover and design, the book is beautifully done.

Harappa has inspired many sensitive hearts and shall continue to do so. More recently from the grandmaster of Urdu metaphysical poetry Majeed Amjad to the distinctively lyrical Ali Akbar Natiq, it has inspired poems such as Kunwan, Harappa and Safeer-e-Laila. We now have Hariyupiya to add to texts that should fire the imagination of anyone who is filled with a sense of wonder whilst thinking about the remote past.

Wistful, romantic, lyrically told, well-researched and richly imagined – Hina Jamshed's Hariyupiya envisions not only a Harappa that could well have existed, but also, one that one would love to have existed. A fine addition this to Urdu historical fiction and the Pakistani novel genres.

The year 2023 so far has been a good one for Urdu fiction in general and Urdu historical fiction in particular. Sahiwal-based Urdu scholar, academic and writer Hina Jamshed has penned a novel called Hariyupiya, published by Book Corner Jhelum, that I have just finished reading. Veteran writer Tahira Iqbal has also published a new novel called Harappa, published by the same publisher, that I have just started reading. Having focused in one of the six eras of my own novel Snuffing Out the Moon (translated as Chand Ko Gul Karen to Hum Janen) on the Indus Valley Civilisation, I was and am particularly intrigued to discover how these two novelists have envisioned and depicted Harappa and its civilisation.

Three things stood out for me as great positives in Hina Jamshed's novel.

The first - essential for all good historical fiction - is her research. Living in close proximity to the site of the glorious ancient city, she appears to have dug deep into archives, secondary literature and relevant available texts and materials. This not only lends invaluable authenticity to what she writes - as can be easily discerned by someone who is familiar with the scholarly literature - but also appreciable texture, detailing and heft to her descriptions.

While research is an essential ingredient, imagination is equally, if not more, important. Because with limited historical understanding of the place and the era, it is imagination that must fill multiple gaps. This is the second aspect that I wish to highlight. It is apparent that Hina Jamshed has roamed frequently in the silent, mysterious streets of the ancient city, breathing in its atmosphere, listening to leftover whispers from bygone times, and sniffing the fragrance of bygone days. No wonder her storytelling is evocative.

Thirdly I wish to emphasise that for historical fiction it is very important to try hard and imagine things as they actually could have been, as opposed to how one wants them or would like them to be. Here too the novelist puts forth something that is compelling and persuasive. It is an imagined Harappa that is more likely to have existed than not. This I must stress is quite an achievement as there are so many places where the writer can falter while writing a historical novel.

I am not one for writing reviews that paraphrase stories and give away the plot. But in brief, the narrative revolves around two friends Abhaya and Baasa, who are craftsmen of beads and pottery (Jamshed goes into exquisite details of the arts and crafts of the time) who travel to Harappa from the much smaller Indus Valley Civilisation community of Kalibangan in Rajasthan. Accompanying them are Baasa’s daughter - young, charming and pretty girl Gaika - his young son, a child referred to as Balak Komail. Harappa looms gloriously on the horizon at the end of their long journey as the boatman old Sudhewa leads them to it. Grand, well-organised, prudently governed, aesthetic and overwhelming. The city’s high priest, as it turns out, is benevolent and wise. There are black sheep amongst the defenders of the city but on the whole the place is a well-oiled, thrumming engine of trade, commerce, culture and the arts. Yearly floods pose the major threat to it. Else the city thrives and has trade tentacles that extend far and wide to Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, China, Greece, Rome, various Indus Valley Civilisation cities, as well as many other distant lands.

Living in close proximity to the site of the glorious ancient city, she appears to have dug deep into archives, secondary literature and relevant available texts and materials

As the novel progresses, tragedy strikes, a question of justice arises, new and interesting characters appear on the scene, romance stirs, and the story crescendos towards a finale where multiple threats of a deluge, administrative breakdown and aggressive mountain people threaten the main characters and their friends as well as the very survival of the city. The plot is believable, and the characters attract one's curiosity and empathy. The main story and characters are well supplemented by side stories and characters and there is no great predictability to the events, which keeps the reader engaged.

While there are interesting and instructive conversations that I look forward to having with the author, I found Hariyupiya to be a well-constructed and richly imagined novel. What will naturally continue to be matters of scholarly and speculative debate are questions such as: were the Harappans actually ruled by a priest caste, as this novel imagines? What was the level of development of their script? How far did their trade extend? What was their language like - a distinct Dravidian script or something that had a vocabulary that later contributed majorly to the Sanskrit of the invaders (this novel's language is very much Sanskrit based and inspired)? There is much to mull over, especially by us historical fiction writers. Tahira Iqbal's novel is bound to deepen this conversation further and add additional perspective and insight.

I must mention here Hina Jamshed's lyrical prose and an overall sense of deep romance that imbues her narrative. The descriptions and imagery are quite charming. The chapters are short and preceded by a brief saying or sentence fragment as a title that is almost always metaphysical and poetic and sets the tone and mood for what is to follow. Hina Jamshed displays great skill: both as a controller of the plot and characterisation, as well as in terms of her facility with consistently using a language that she fashions to suit an era in the ancient past. While the remote past shall probably always not be fully knowable, Hariyupiya offers a depiction that resonates at multiple levels due to what we know so far about the Harappan civilisation. It is also a past which despite its low points and crises, one would like to imagine for Harappa. A past of great sophistication, organisation and amity, that offers lessons even today in terms of harmonious urban existence.

Brothers Amar and Gagan of Book Corner, like the Brothers Karamazov or the Brothers Grimm, always maintain high standards. Well printed and published, with a striking cover and design, the book is beautifully done.

Harappa has inspired many sensitive hearts and shall continue to do so. More recently from the grandmaster of Urdu metaphysical poetry Majeed Amjad to the distinctively lyrical Ali Akbar Natiq, it has inspired poems such as Kunwan, Harappa and Safeer-e-Laila. We now have Hariyupiya to add to texts that should fire the imagination of anyone who is filled with a sense of wonder whilst thinking about the remote past.

Wistful, romantic, lyrically told, well-researched and richly imagined – Hina Jamshed's Hariyupiya envisions not only a Harappa that could well have existed, but also, one that one would love to have existed. A fine addition this to Urdu historical fiction and the Pakistani novel genres.