Sometimes I wonder that if I were to be teleported to the time when some historical event was in progress, I could experience entirely different realities than what I read in various historians’ accounts about the same event.

I respect all those who spend their time and energy to research the events of history and educate us with analysis based on their research. However, they are like the twelve blindfolded men who are brought to the different sides of elephant, and they are asked to describe the shape by touching various parts of the animal. Their conclusions were based upon which part of the elephant they touch – i.e. subjective experiences and biases of the person touching it.

The history of the Indian Subcontinent is full of paradoxes and historians’ personal tilts and biases. The bloodshed at the time of Partition was so enormous and both sides lost so much that to this day, they only remember their own wounds and forget the wounds they inflicted to other party.

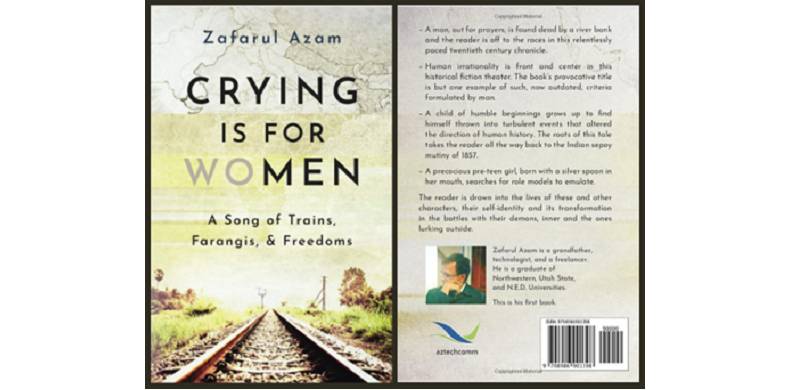

Zafarul Azam, in his brilliant Crying is for Women, uses a fiction and blends it with real events from the Indian Subcontinent in a way may never have been done before. The fictional part is the story of a Muslim family that belongs to the eastern part of Uttar Pradesh: it begins in the early part of the 19th century, and goes to the 21st century. This fictional part depicts the situation of the common people who were forced to suffer by the imperial power, which converted the country with 16% of the global GDP in 1820—before British direct rule—to 2% of the world’s GDP in 1947.

The author does a wonderful job in making sure that the fiction is properly amalgamated with the history. My observation is that critiques of books and movies primarily look at three key features, besides the solid script, to judge the story, namely:

1.) introduction of characters

2.) story-telling

3.) conclusion

The author did a wonderful job in all three aspects.

From time to time, the story gets slowed down, but the reason could be that when fiction is riding on real events, the author must necessarily go by the pace of the real event – no matter how slow it gets.

The author uses the supernatural visions and dreams of the characters from time to time to get the message across. The story is not a narration by the protagonist, but self-conversation and footnotes are used to get the idea across.

For those who search for good fiction to read, and those who want to know more about the history of the Indian Subcontinent from the eyes of common people, Crying is for (Wo)men, available on Amazon, should be their next choice.

The story would indeed teleport the reader to the centre of painful events in history, even as they unfolded.

I respect all those who spend their time and energy to research the events of history and educate us with analysis based on their research. However, they are like the twelve blindfolded men who are brought to the different sides of elephant, and they are asked to describe the shape by touching various parts of the animal. Their conclusions were based upon which part of the elephant they touch – i.e. subjective experiences and biases of the person touching it.

The history of the Indian Subcontinent is full of paradoxes and historians’ personal tilts and biases. The bloodshed at the time of Partition was so enormous and both sides lost so much that to this day, they only remember their own wounds and forget the wounds they inflicted to other party.

Zafarul Azam, in his brilliant Crying is for Women, uses a fiction and blends it with real events from the Indian Subcontinent in a way may never have been done before. The fictional part is the story of a Muslim family that belongs to the eastern part of Uttar Pradesh: it begins in the early part of the 19th century, and goes to the 21st century. This fictional part depicts the situation of the common people who were forced to suffer by the imperial power, which converted the country with 16% of the global GDP in 1820—before British direct rule—to 2% of the world’s GDP in 1947.

The author does a wonderful job in making sure that the fiction is properly amalgamated with the history. My observation is that critiques of books and movies primarily look at three key features, besides the solid script, to judge the story, namely:

1.) introduction of characters

2.) story-telling

3.) conclusion

The author did a wonderful job in all three aspects.

From time to time, the story gets slowed down, but the reason could be that when fiction is riding on real events, the author must necessarily go by the pace of the real event – no matter how slow it gets.

The author uses the supernatural visions and dreams of the characters from time to time to get the message across. The story is not a narration by the protagonist, but self-conversation and footnotes are used to get the idea across.

For those who search for good fiction to read, and those who want to know more about the history of the Indian Subcontinent from the eyes of common people, Crying is for (Wo)men, available on Amazon, should be their next choice.

The story would indeed teleport the reader to the centre of painful events in history, even as they unfolded.