Nearly two centuries have passed since John Keats, one of the most celebrated lyrical poets of English literature, died of tuberculosis. He was only twenty-five years old. Earlier, one of his brothers and mother, both of whom he had nursed, had also died of the same illness.

A number of books have been written about Keats that have kept alive the interest of both scholars and students on his alluring romantic poetry, the interest bolstered by his brief, tragic life and his intense, tumultuous love affair with Fanny Brawne, the young woman who was his onetime neighbor. One of the more recent books by Stanley Plumly, Posthumous Keats, borrows its title from Keats' own characterisation of his final years as posthumous life.

Plumly, a poet and professor of literature, has authored an unconventional biography which does not chronicle or explore the poet's life in any chronological sequence. Instead, the book comprises a series of essays, concentrating on themes extracted from Keats' life, but of the author's choosing. Especially poignant are the meticulous details of the final years of Keats' life in Rome and the powerful portrayal of the relentless progression of the disease that mercilessly sapped his physical strength without impairing his cognitive faculties, finally extinguishing his life.

Keats in his lifetime never foresaw the success and fame that his romantic poetry generated almost a century following his death. His gravestone in the protestant crematory in Rome bears the inscription, “Here Lies One Whose Name Was Writ in Water”; the phrase was engraved at Keats specific direction, reflecting his pessimistic appraisal of his life's work as he approached his final hours.

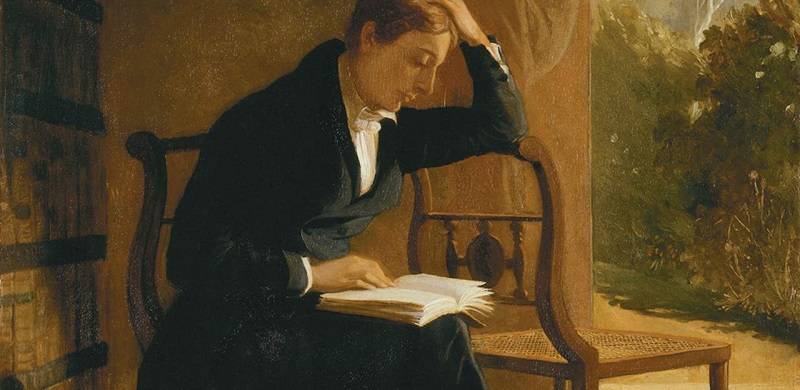

Born in London of a modest family background, Keats enrolled as a trainee in surgical medicine at Guy's Hospital and in time became qualified to practice surgery. However, he soon realized that he was not suited to the practice of medicine and was far more drawn to poetry and literature. At the age of 21, he produced one of his most acclaimed epic poems, Endymion, A Poetic Romance, a long ode based on Greek mythology in which a handsome young shepherd prince was passionately loved by the moon-goddess, Selene. Endymion opens with the verse, "A thing of beauty is a joy forever," which has become a favorite line of Keats' many admirers. The poem, however, was not well received in literary circles in England, and Keats came in for withering criticism on several fronts. Even his family's humble origin became a cause for some to disapprove of his literary masterpieces, and the magazines that chose to publish them were similarly excoriated.

Keats was not discouraged and for a brief period in 1819, a mere three years before his death, he displayed spectacular bursts of creativity. In just a few months, he managed to compose the three most beautiful and stunning pieces of poetry in English language, Ode on a Grecian Urn, Ode to a Nightingale and Ode on Melancholy. The phrase, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,” from his poem, Ode on a Grecian Urn, has become a universal favorite of poetry lovers.

Significantly, this period also coincided with the time when he was getting into a romantic relationship with the young woman living next door, Fanny Brawne. The tempestuous relationship would both enthrall and torment him for the rest of his short life. Although his close friends disapproved of the romance as in their view it distracted him from pursuing his literary efforts, it, nevertheless, blossomed and Fanny and Keats got engaged to marry.

While flourishing as a poet, Keats was about to be inflicted with his family's curse. Following the death of his brother of the disease, he himself started to show symptoms of tuberculosis. He had been trained in medicine and when he first coughed up blood, he immediately realized its sinister implications, and at the sight of it, exclaimed in anguish, "That drop of blood is my death warrant, I must die."

While he had reached the correct diagnosis, the doctors who attended to him did not, believing that the episode was caused variably by his emotional instability or a problem originating in his stomach rather than lungs. No sophisticated methods of diagnosis or treatment existed at the times, and he was treated with bloodletting, and placed on a starvation diet, none of which did any good.

On the advice of his friends Keats sailed for Italy as it was believed that the warm, salubrious climate of the country might cure his malaise. Initially, Rome's dazzling lights and exotic sights seemed to have cheered up the ailing poet, but only temporarily. He was diligently nursed by his friend, Joseph Severn, as bouts of cough, fever and hemorrhage became severe and frequent. The inevitable end came in February 1821. Keats was the youngest to die of the three famed contemporary English romantic poets, Keats, Shelley and Byron, none of whom lived to see his 40th birthday. By strange coincidence, John Keats, Percy Shelley and Lord Byron, were in Italy at the same time, and while Keats and Shelley died there, Lord Byron died in 1824 in nearby Greece where he had gone to support that country’s war of independence. Shelley died in the bay of La Spezia, Italy, in March 1822 in a tragic boating accident.

Keats' contributions to literature were not limited to the exquisite poetry he wrote. When his letters to Fanny Brawne were published in 1878, after both of them had died, they aroused intense interest. The love letters, highlighting Keats intense passion, overwhelming love and at times, his transparent jealousy, are regarded as the most beautiful ever written in the English language. Only thirty-nine letters and notes were saved by Fanny Brawne, while none of those written by her to Keats survive. Plumly in his book has reproduced a selection of some of them, and while lyrical, they are uncharacteristically devoid of any poetry.

During the last few months of his life spent in Rome and Naples, Keats was too emotionally fragile to write to Fanny, and even the sight of her handwriting was upsetting to him. The last note he received from her; he did not read. Instead, he asked that it be placed in his coffin along with a lock of her hair. While Keats' devotion to Fanny Brawne was complete, whether she reciprocated his love with the same passion has remained a subject of much speculation.

A number of books have been written about Keats that have kept alive the interest of both scholars and students on his alluring romantic poetry, the interest bolstered by his brief, tragic life and his intense, tumultuous love affair with Fanny Brawne, the young woman who was his onetime neighbor. One of the more recent books by Stanley Plumly, Posthumous Keats, borrows its title from Keats' own characterisation of his final years as posthumous life.

Plumly, a poet and professor of literature, has authored an unconventional biography which does not chronicle or explore the poet's life in any chronological sequence. Instead, the book comprises a series of essays, concentrating on themes extracted from Keats' life, but of the author's choosing. Especially poignant are the meticulous details of the final years of Keats' life in Rome and the powerful portrayal of the relentless progression of the disease that mercilessly sapped his physical strength without impairing his cognitive faculties, finally extinguishing his life.

Keats in his lifetime never foresaw the success and fame that his romantic poetry generated almost a century following his death. His gravestone in the protestant crematory in Rome bears the inscription, “Here Lies One Whose Name Was Writ in Water”; the phrase was engraved at Keats specific direction, reflecting his pessimistic appraisal of his life's work as he approached his final hours.

Born in London of a modest family background, Keats enrolled as a trainee in surgical medicine at Guy's Hospital and in time became qualified to practice surgery. However, he soon realized that he was not suited to the practice of medicine and was far more drawn to poetry and literature. At the age of 21, he produced one of his most acclaimed epic poems, Endymion, A Poetic Romance, a long ode based on Greek mythology in which a handsome young shepherd prince was passionately loved by the moon-goddess, Selene. Endymion opens with the verse, "A thing of beauty is a joy forever," which has become a favorite line of Keats' many admirers. The poem, however, was not well received in literary circles in England, and Keats came in for withering criticism on several fronts. Even his family's humble origin became a cause for some to disapprove of his literary masterpieces, and the magazines that chose to publish them were similarly excoriated.

Keats was not discouraged and for a brief period in 1819, a mere three years before his death, he displayed spectacular bursts of creativity. In just a few months, he managed to compose the three most beautiful and stunning pieces of poetry in English language, Ode on a Grecian Urn, Ode to a Nightingale and Ode on Melancholy. The phrase, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty,” from his poem, Ode on a Grecian Urn, has become a universal favorite of poetry lovers.

Significantly, this period also coincided with the time when he was getting into a romantic relationship with the young woman living next door, Fanny Brawne. The tempestuous relationship would both enthrall and torment him for the rest of his short life. Although his close friends disapproved of the romance as in their view it distracted him from pursuing his literary efforts, it, nevertheless, blossomed and Fanny and Keats got engaged to marry.

While flourishing as a poet, Keats was about to be inflicted with his family's curse. Following the death of his brother of the disease, he himself started to show symptoms of tuberculosis. He had been trained in medicine and when he first coughed up blood, he immediately realized its sinister implications, and at the sight of it, exclaimed in anguish, "That drop of blood is my death warrant, I must die."

While he had reached the correct diagnosis, the doctors who attended to him did not, believing that the episode was caused variably by his emotional instability or a problem originating in his stomach rather than lungs. No sophisticated methods of diagnosis or treatment existed at the times, and he was treated with bloodletting, and placed on a starvation diet, none of which did any good.

On the advice of his friends Keats sailed for Italy as it was believed that the warm, salubrious climate of the country might cure his malaise. Initially, Rome's dazzling lights and exotic sights seemed to have cheered up the ailing poet, but only temporarily. He was diligently nursed by his friend, Joseph Severn, as bouts of cough, fever and hemorrhage became severe and frequent. The inevitable end came in February 1821. Keats was the youngest to die of the three famed contemporary English romantic poets, Keats, Shelley and Byron, none of whom lived to see his 40th birthday. By strange coincidence, John Keats, Percy Shelley and Lord Byron, were in Italy at the same time, and while Keats and Shelley died there, Lord Byron died in 1824 in nearby Greece where he had gone to support that country’s war of independence. Shelley died in the bay of La Spezia, Italy, in March 1822 in a tragic boating accident.

Keats' contributions to literature were not limited to the exquisite poetry he wrote. When his letters to Fanny Brawne were published in 1878, after both of them had died, they aroused intense interest. The love letters, highlighting Keats intense passion, overwhelming love and at times, his transparent jealousy, are regarded as the most beautiful ever written in the English language. Only thirty-nine letters and notes were saved by Fanny Brawne, while none of those written by her to Keats survive. Plumly in his book has reproduced a selection of some of them, and while lyrical, they are uncharacteristically devoid of any poetry.

During the last few months of his life spent in Rome and Naples, Keats was too emotionally fragile to write to Fanny, and even the sight of her handwriting was upsetting to him. The last note he received from her; he did not read. Instead, he asked that it be placed in his coffin along with a lock of her hair. While Keats' devotion to Fanny Brawne was complete, whether she reciprocated his love with the same passion has remained a subject of much speculation.