One of independent India’s greatest challenges was to integrate its vast mosaic of linguistic, ethnic and religious entities into a democratic, federal order with an effective centre. The Motilal Nehru Report of 1928 had already laid down the overall framework for such integration by recognising language as the fundamental bond underpinning different nationalities upon which distinct provinces could be established, but achieving it in practice after independence was a daunting task.

The reason was that the partition of India justified on the alleged incompatibility of religious communities -- specifically Hindus and Muslims -- to live together in peace and dignity in one state dashed the ideal upon which the Indian freedom struggle had been launched and fought. It induced in the erstwhile Indian leadership’s oversensitivity to any subsequent attempts to secession by any group from what became the independent Indian Dominion in mid-August 1947.

However, the founding fathers remained steadfast to the overall democratic commitment to recognise the plurality and diversity of ethnicity, language and culture and upon such a basis grant separate statehood and other configurations so that a fair share in the allocation of resources for development could be ensured.

Thus, the original nine provinces established by British largely on administrative and defence concerns which were designated in the Indian constitution as states and other territories have now been supplanted by 29 new states and other configurations. The 562 princely states have been amalgamated in them.

In the initial stages, the efforts of Home Minister Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and VP Menon were crucial in ensuring that the 562 princely states voluntarily agreed to join the Indian Union. Both carrot and stick methods were used to dissuade those few princely states which wanted to opt out of the Union.

In the second round, the Reorganisation Committee accepted linguistic and ethnic criteria as legitimate basis for creating new states and other configurations of smaller groups. Thus the breakup of the Bombay Presidency in 1960 created the states of Maharashtra and Gujarat but Mumbai was allocated to Maharashtra, while in 1966 the Indian Punjab was split into Hindi-speaking Haryana and Punjabi-speaking Punjab, and Chandigarh was made the joint capital of both these states. Some territories of the former Indian Punjab were given to Himachal Pradesh.

These and several other such examples are indicative of a flexible approach and varying formulae being adopted to grant territories and redrawing maps. It can be noted that such changes were based on bipartisan consensus although the BJP was opposed to the creation of new states. It has now toned down its opposition to it. It is note worthy that privy purses for the rulers of princely states which were agreed originally were abolished in 1971 by Indira Gandhi.

However, attempts to secede have been crushed by the overwhelming use of force by the state. Examples are the separatist movements of Nagaland, the Khalistan movement and the Indian Kashmir.

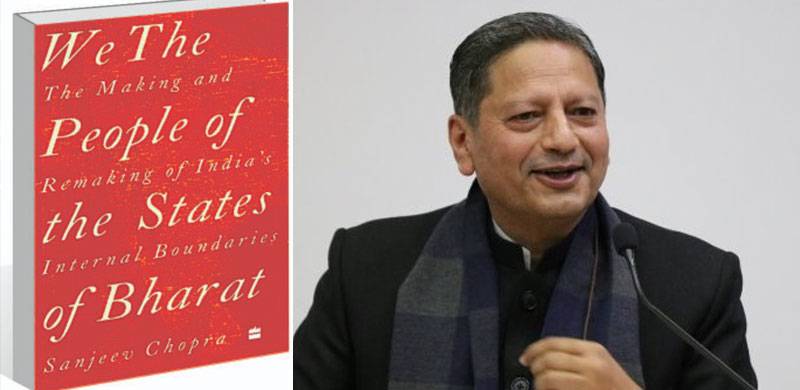

Dr Sanjeev Chopra, a historian and retired IAS officer, tells this fascinating story about India’s approach on mapping state boundaries in a crisp prose. His fascination from school days with geography and maps induced him to attempt this amazing research. Drawing upon the reports of the States Reorganisation Commission and Linguistic Reorganisation Commission records from state papers as well as the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, he painstakingly and admirably analyses the changing maps, nomenclature and the concomitant politics of give and take. The result is a masterpiece of a compendium, which will prove to be seminal, and a standard reference on this subject.

For us in Pakistan, there are many lessons to be learnt. Being an ideological state, the policy makers in Pakistan have never given due recognition and respect to regional cultures and their languages. The imposition of Urdu, the mother tongue of only 7 percent of the total population of Pakistan, at the expense of Pashto, Punjabi, Sindhi and Balochi languages, has generated considerable grievances in many provinces. And, the provinces of Khyber-Pakhtunkhawa and Sindh, which were inherited at the time of independence, and Balochistan which was created in 1969 as a full province, remain largely unwieldy administrative units.

It can be worthwhile learning from India how to redraw boundaries and maps of these provinces to create new ones so that services to the people become paramount instead of vain concerns for ideological dogmatism. Also, although Zulfikar Ali Bhutto abolished the privy purse for rulers of princely states, an annual pension was granted to them. The pensions were increased in 2017 from Rs 25,000 to Rs 500,000. There is no justification for the continuation of such pensions.

The reason was that the partition of India justified on the alleged incompatibility of religious communities -- specifically Hindus and Muslims -- to live together in peace and dignity in one state dashed the ideal upon which the Indian freedom struggle had been launched and fought. It induced in the erstwhile Indian leadership’s oversensitivity to any subsequent attempts to secession by any group from what became the independent Indian Dominion in mid-August 1947.

We the People of the States of Bharat

By Sanjeev Chopra

HarperCollins Publishers India, 2022

However, the founding fathers remained steadfast to the overall democratic commitment to recognise the plurality and diversity of ethnicity, language and culture and upon such a basis grant separate statehood and other configurations so that a fair share in the allocation of resources for development could be ensured.

Thus, the original nine provinces established by British largely on administrative and defence concerns which were designated in the Indian constitution as states and other territories have now been supplanted by 29 new states and other configurations. The 562 princely states have been amalgamated in them.

In the initial stages, the efforts of Home Minister Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and VP Menon were crucial in ensuring that the 562 princely states voluntarily agreed to join the Indian Union. Both carrot and stick methods were used to dissuade those few princely states which wanted to opt out of the Union.

In the second round, the Reorganisation Committee accepted linguistic and ethnic criteria as legitimate basis for creating new states and other configurations of smaller groups. Thus the breakup of the Bombay Presidency in 1960 created the states of Maharashtra and Gujarat but Mumbai was allocated to Maharashtra, while in 1966 the Indian Punjab was split into Hindi-speaking Haryana and Punjabi-speaking Punjab, and Chandigarh was made the joint capital of both these states. Some territories of the former Indian Punjab were given to Himachal Pradesh.

These and several other such examples are indicative of a flexible approach and varying formulae being adopted to grant territories and redrawing maps. It can be noted that such changes were based on bipartisan consensus although the BJP was opposed to the creation of new states. It has now toned down its opposition to it. It is note worthy that privy purses for the rulers of princely states which were agreed originally were abolished in 1971 by Indira Gandhi.

It can be worthwhile learning from India how to redraw boundaries and maps of these provinces to create new ones so that services to the people become paramount instead of vain concerns for ideological dogmatism.

However, attempts to secede have been crushed by the overwhelming use of force by the state. Examples are the separatist movements of Nagaland, the Khalistan movement and the Indian Kashmir.

Dr Sanjeev Chopra, a historian and retired IAS officer, tells this fascinating story about India’s approach on mapping state boundaries in a crisp prose. His fascination from school days with geography and maps induced him to attempt this amazing research. Drawing upon the reports of the States Reorganisation Commission and Linguistic Reorganisation Commission records from state papers as well as the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, he painstakingly and admirably analyses the changing maps, nomenclature and the concomitant politics of give and take. The result is a masterpiece of a compendium, which will prove to be seminal, and a standard reference on this subject.

For us in Pakistan, there are many lessons to be learnt. Being an ideological state, the policy makers in Pakistan have never given due recognition and respect to regional cultures and their languages. The imposition of Urdu, the mother tongue of only 7 percent of the total population of Pakistan, at the expense of Pashto, Punjabi, Sindhi and Balochi languages, has generated considerable grievances in many provinces. And, the provinces of Khyber-Pakhtunkhawa and Sindh, which were inherited at the time of independence, and Balochistan which was created in 1969 as a full province, remain largely unwieldy administrative units.

It can be worthwhile learning from India how to redraw boundaries and maps of these provinces to create new ones so that services to the people become paramount instead of vain concerns for ideological dogmatism. Also, although Zulfikar Ali Bhutto abolished the privy purse for rulers of princely states, an annual pension was granted to them. The pensions were increased in 2017 from Rs 25,000 to Rs 500,000. There is no justification for the continuation of such pensions.