If there is a silver lining to the unending political chaos, it is the vigorous debate on the army’s damaging role in politics and governance. There is a growing realization that there cannot be real democracy in Pakistan without firm civilian control over the armed forces. Because of the current political standoff, many people see the need to bell the cat and restore genuine democracy and plant lasting roots for it.

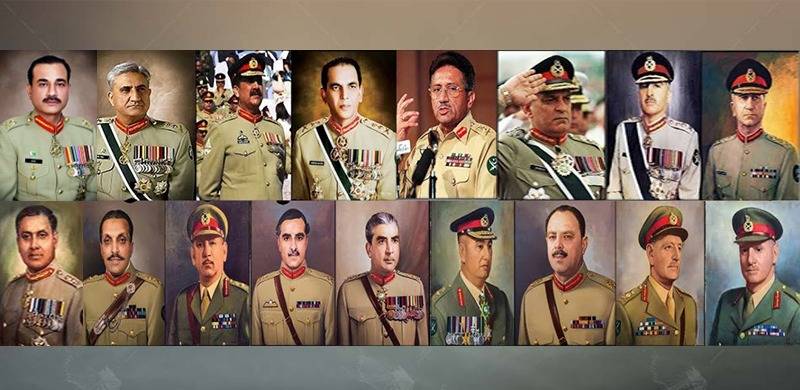

Based on recent pronouncements, the army’s senior leadership has noted civilian misgivings and expressed its neutrality in politics. But it is hard to predict if the internal glasnost will last or lead to an inner transformation in the institution. Sadly, Pakistan is too used to generals being politicians in uniform more than leaders of armies. And the military has always had a strained relationship with democracy — its ham-fisted authoritarian approach to resolving social, economic, and problems have been at odds with the cautious deliberations of a democracy.

Ending military partisanship and political engineering would mean giving up power and control. With the existing civil-military balance so heavily skewed in its favour, the military will not find it easy to relinquish its self-appointment role as the referee in domestic politics. And refrain from political actions that undermine elections or hinder civilian leadership.

Ironically, the outgoing army chief, General Bajwa, quoted US General Douglas MacArthur in his farewell speech. MacArthur led US forces in the Pacific to victory against fascist Japan and democratized the defeated country. But he was fired by President Truman for insubordination during the Korean war. In contrast, no Pakistani general can claim credit for defeating an external enemy, but few generals have lost their jobs for questioning the policies of the civilian government.

In an earlier speech, Bajwa said that the fall of East Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh in 1971 was not a military but a political failure. A more considered view is that it was the army’s disdain for democratic institutions that made it impossible for a stable democracy to emerge that was the primary cause for the dismemberment of Pakistan. Arguably, the spiral of violence, radicalization, polarization, repression, and revenge politics leading to the 1971 debacle was because of political instability created by authoritarian tendencies.

Unfortunately, it is a lesson not heeded by the power elite of a truncated Pakistan. The military remains the fountainhead of power. It selects and manipulates political leaders and parties in a guided democracy. And politicians are yet to learn that military intervention is not a democratic mechanism. Without the military option, politicians would have to find negotiated solutions with the tools they have within the political system.

Countries have learned from bitter experiences that a struggling democracy is better than direct or indirect military rule. But in Pakistan, an enormous obstacle is that historically democracy has not been part of the culture or psyche of the country. Top-down decision-making without the involvement of the grassroots is the norm. The people, seeing no alternative, expect miracles from the broken hybrid system of government.

The road from military neutrality in politics to changing the power balance in favour of civilians will be long and tortuous. It can follow a tested roadmap. One, the power to hire and fire the senior leadership of the armed forces must rest with the civilian leadership. Two, the civilian branches of government should oversee the military’s personnel decisions and budgets. Three, the executive and parliament should monitor the activities of the military intelligence services. Fourth, the people’s representatives must prescribe the precise role of the armed forces within the national government. Fifth, the military is trained to defend national sovereignty within the legal framework of a democratic society. Sixth, democratic institutions like the media and the courts should have access to the workings of the armed forces.

We hope the ongoing public debate leads to fresh thinking on civil-military relations. The survival and progress of a state and society very close to collapse are at stake.

The writer is an analyst and commentator. He can be reached at shgcci@gmail.com.

Based on recent pronouncements, the army’s senior leadership has noted civilian misgivings and expressed its neutrality in politics. But it is hard to predict if the internal glasnost will last or lead to an inner transformation in the institution. Sadly, Pakistan is too used to generals being politicians in uniform more than leaders of armies. And the military has always had a strained relationship with democracy — its ham-fisted authoritarian approach to resolving social, economic, and problems have been at odds with the cautious deliberations of a democracy.

Ending military partisanship and political engineering would mean giving up power and control. With the existing civil-military balance so heavily skewed in its favour, the military will not find it easy to relinquish its self-appointment role as the referee in domestic politics. And refrain from political actions that undermine elections or hinder civilian leadership.

Ironically, the outgoing army chief, General Bajwa, quoted US General Douglas MacArthur in his farewell speech. MacArthur led US forces in the Pacific to victory against fascist Japan and democratized the defeated country. But he was fired by President Truman for insubordination during the Korean war. In contrast, no Pakistani general can claim credit for defeating an external enemy, but few generals have lost their jobs for questioning the policies of the civilian government.

One, the power to hire and fire the senior leadership of the armed forces must rest with the civilian leadership. Two, the civilian branches of government should oversee the military’s personnel decisions and budgets.

In an earlier speech, Bajwa said that the fall of East Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh in 1971 was not a military but a political failure. A more considered view is that it was the army’s disdain for democratic institutions that made it impossible for a stable democracy to emerge that was the primary cause for the dismemberment of Pakistan. Arguably, the spiral of violence, radicalization, polarization, repression, and revenge politics leading to the 1971 debacle was because of political instability created by authoritarian tendencies.

Unfortunately, it is a lesson not heeded by the power elite of a truncated Pakistan. The military remains the fountainhead of power. It selects and manipulates political leaders and parties in a guided democracy. And politicians are yet to learn that military intervention is not a democratic mechanism. Without the military option, politicians would have to find negotiated solutions with the tools they have within the political system.

Countries have learned from bitter experiences that a struggling democracy is better than direct or indirect military rule. But in Pakistan, an enormous obstacle is that historically democracy has not been part of the culture or psyche of the country. Top-down decision-making without the involvement of the grassroots is the norm. The people, seeing no alternative, expect miracles from the broken hybrid system of government.

The road from military neutrality in politics to changing the power balance in favour of civilians will be long and tortuous. It can follow a tested roadmap. One, the power to hire and fire the senior leadership of the armed forces must rest with the civilian leadership. Two, the civilian branches of government should oversee the military’s personnel decisions and budgets. Three, the executive and parliament should monitor the activities of the military intelligence services. Fourth, the people’s representatives must prescribe the precise role of the armed forces within the national government. Fifth, the military is trained to defend national sovereignty within the legal framework of a democratic society. Sixth, democratic institutions like the media and the courts should have access to the workings of the armed forces.

We hope the ongoing public debate leads to fresh thinking on civil-military relations. The survival and progress of a state and society very close to collapse are at stake.

The writer is an analyst and commentator. He can be reached at shgcci@gmail.com.