The famed Rohilla clans were mainly drawn from Pashtun tribes. They migrated from their barren surroundings in the Hindukush and, its extension, the Koh-e-Suleiman, to the fertile lands of North India in the post-Aurangzeb Völkerwanderung. Some of them were attracted by – and wandered into – the turmoil and vacuum of central India where their fighting abilities found lucrative employment. However, they mostly settled in a cool corner at the foothills of the Himalayas between northeast Punjab and northwest Awadh (Oudh).

Subsequently, after the British East India Company (BEIC) emerged victorious in the tussle to control India, some of the Rohilla Pathans accepted the reality of British supremacy and agreed to rule under their sovereignty as their vassals. Their princely states of Bhopal, Rampur, Tonk, Malerkotla, Pataudi and a host of others were established under these terms. It is an interesting and astonishing fact that the princely Afghan rulers and their descendants transformed from pitiless fighters into the most enlightened rulers in India. They established libraries and educational institutions, encouraged art and literature, and maintained peace and order.

Rohillas are often termed as ferocious and their name has earned much notoriety because of the cruelties inflicted by Ghulam Qadir Rohilla on the Mughal household of Emperor Shah Alam II in the mid-1780s. However, they were more educated, cultured and enterprising than many Indians. Lord Macaulay was one of the most prominent writers and thinkers of early 19th century, who served on the council of the Governor General as law member between 1834 and 1838, and who was responsible for introducing western education in India. In his long essay on Governor General Warren Hastings, Macaulay wrote thus about the Rohilla Pathans, "To this day they are regarded as the best of all sepoys at the cold steel; and […] the only natives of India to whom the word "gentleman" can with perfect propriety he applied, are to be found among the Rohillas."

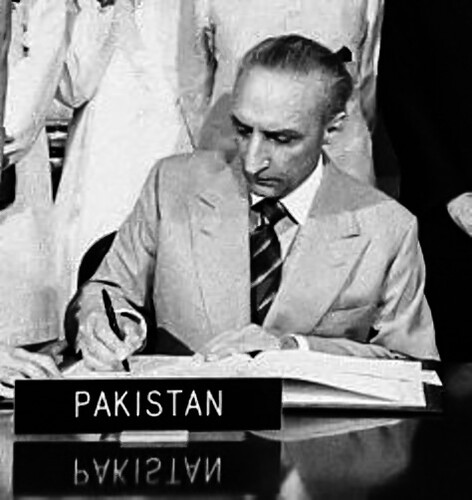

The above context should facilitate in understanding the persons of Sahibzada Yaqub Khan, who belonged to the royal family of the Princely State of Rampur and was a descendant of Rohilla Pathans. His ancestors had fought against the British in the second half of the 18th century. Rampur State was created in 1774 under the tutelage of the British East India Company, when Rohillas were defeated by the combined British Bengal and Awadh (Oudh) Armies. Starting with its progenitor Faizullah Khan, a son of the founder of the Rohikhand State and a direct ancestor of the Sahibzada, Rampur rulers patronised art and music. Faizullah established a library that subsequently came to be known as Raza Library, and which was one of the best endowed libraries of India – with thousands of manuscripts, paintings, documents and artefacts.

The above context should facilitate in understanding the persons of Sahibzada Yaqub Khan, who belonged to the royal family of the Princely State of Rampur and was a descendant of Rohilla Pathans. His ancestors had fought against the British in the second half of the 18th century. Rampur State was created in 1774 under the tutelage of the British East India Company, when Rohillas were defeated by the combined British Bengal and Awadh (Oudh) Armies. Starting with its progenitor Faizullah Khan, a son of the founder of the Rohikhand State and a direct ancestor of the Sahibzada, Rampur rulers patronised art and music. Faizullah established a library that subsequently came to be known as Raza Library, and which was one of the best endowed libraries of India – with thousands of manuscripts, paintings, documents and artefacts.

Rampur produced many stalwarts in politics, literature and arts. It bred people like Maulana Muhammad Ali Jauhar (Khilafat Movement), Maulana Shaukat Ali Gauhar (Khilafat Movement), Abul Kalam Azad (politician, President of All India Congress), Dr Manzoor Ahmad (scientist/philosopher), Muhammad Ali (Pakistani actor), Obaidullah Baig (intellectual/TV artist), Shama Zaidi (Indian screenplay writer), Raza Murad (Indian actor), Pran (Indian actor), Athar Shah Khan Jaidi (Pakistani TV/drama) and many others. It is, therefore, no surprise that the land gave birth and raised a prodigious son like Sahibzada Yaqub, who was universally respected, first as a soldier and then as a diplomat.

Ali Hamid, a retired major general of the Pakistan Army, served in the armoured corps, the same arm to which Sahibzada Yaqub was commissioned in 1940. He is a gifted writer and is the author of At the Forward Edge of Battle - A History of the Pakistan Armoured Corps 1938-2016 in two volumes and Forged in the Furnace of Battle: The War History of 26 Cavalry Chhamb Operations 1971. He also contributes regularly to The Friday Times – Naya Daur, the Express Tribune and many other periodicals and journals. He is one of the most appropriate writers to take up the subject of a soldier, a war and the life of a POW.

The book under review covers four crucial years of Sahibzada Yaqub’s life; from January 1941, when his regiment departed for Egypt, through May 1942 when he became a POW, till his release and arrival in London in April 1945, and his subsequent repatriation to India two months later.

During these four years, Sahibzada Yaqub lived life in top gear. He was only 22 years of age when he left India with his regiment, but underwent experiences that an ardent adventurer can only hope to achieve in a lifetime. He started his sojourn by the first sea voyage of his life and ended by his first air travel. In these years, he travelled or force-marched through several countries of the Middle East and Europe. He took part in some of the most famous battles of WW II and served with soldiers of several nationalities, was captured by ‘efficient’ Germans and detained under the ‘disorganised’ Italians, survived on meagre POW rations and then dined lavishly in the best restaurants of London when freed, wore a single uniform for weeks on end but went on to wear hand-stitched Savile Row suits, travelled in windowless cramped train carriages and then in VIP aircraft, was treated badly by his goalers and later honoured by his C-in-C. In short, the book depicts extremes of deprivation and indulgence that he experienced during those years.

As the book is based on Sahibzada Yaqub's wartime log, the reader is astonished at the details left behind by the meticulous officer: details that enabled a worthy writer like Ali Hamid to complete the history of the man and his life relating to those four years; one of which was spent in the Middle East and three as a POW in German hands.

As would be expected, the descriptions by the author of military equipment and organisation are brilliant. The following sentence, with its fine details on page 32 made pleasurable reading, "They were provided with better mobility with tracked universal carriers and better firepower with 3-inch mortars and 2-pounder anti-tank guns mounted on 6-ton trucks."

His other descriptions are equally eloquent, such as that on pages 33-34 of the Service Guide to Cairo about recreational facilities available in the city. Similarly, a description of prisoners' feelings as they waited for the US forces to release them from Oflag-79, their POW camp (page 148) is very impressive. These depictions in words are like paintings on a canvas or sketching on paper.

The experience of being a POW for a long time is physically difficult and psychologically grim. Our own POWs of the 1971 war tell stories of deprivation and hardship that are similar to the story of Sahibzada Yaqub as depicted in this book. After being made a POW by the German army, he and his fellow prisoners were handed over to the Italian forces. They had to walk through the desert without food or water. In fact, the food shortage was so acute that their Italian captors had to release all non-commissioned prisoners. The officer prisoners lived in crammed quarters and suffered through shortages of food and water. Their voyage through the Mediterranean sea in Italian cargo ships, as narrated in the book, was perilous because they were being sunk regularly by British submarines – with several hundred Allied prisoners losing their life.

Sahibzada Yaqub’s impeccable behaviour throughout his life was forged early in his career, as can be discerned in this book. His displayed courage and moral strength under incarceration. He didn't wilt in those trying circumstances. Instead, as depicted in detail by Ali Hamid, he used his forced leisure time well to become a polyglot. He learnt to speak four European languages, including German, French, Russian and Italian. It is often said that he had a knack for learning foreign languages as if his brain were endowed or wired to do so. In actual fact, it was simply his determination and hard work, along with his superior intellect, that enabled him in his mid-20s to learn all these languages. Later in life, as a diplomat, he could simultaneously carry out discussions with four different nationals in their own mother tongue.

The hallmark of storytelling is to pick up a small insignificant incident, event or a person and build it into an interesting readable tale without ignoring facts. Syed Ali Hamid is a natural storyteller. Several of his descriptions in the book are based on the routine life of any POW camp, but he has converted them into interesting tales. His accounts of preparation for theatre (page 73), of a concert in December 1944 at a POW camp named Oflag-79 in Brunswick (page 128} and that of Savile Row (page 166) are fascinating.

The broad perceptions of the author are evident in many parts of the book. For instance, writing about Sahibzada's drive through the Jewish-owned pleasantly green fields of northern Palestine on his regiment's recall to Egypt from Syria in February 1942, the author writes, "In some ways, it reminded him of his parents’ house in Dehradun with its fruit trees." Or this: "Sahibzada Yaqub sat in his truck and watched the sun sink into the desert sand." Clearly, these are extrapolations by the author through his own visualisation of events, which make the book an interesting read

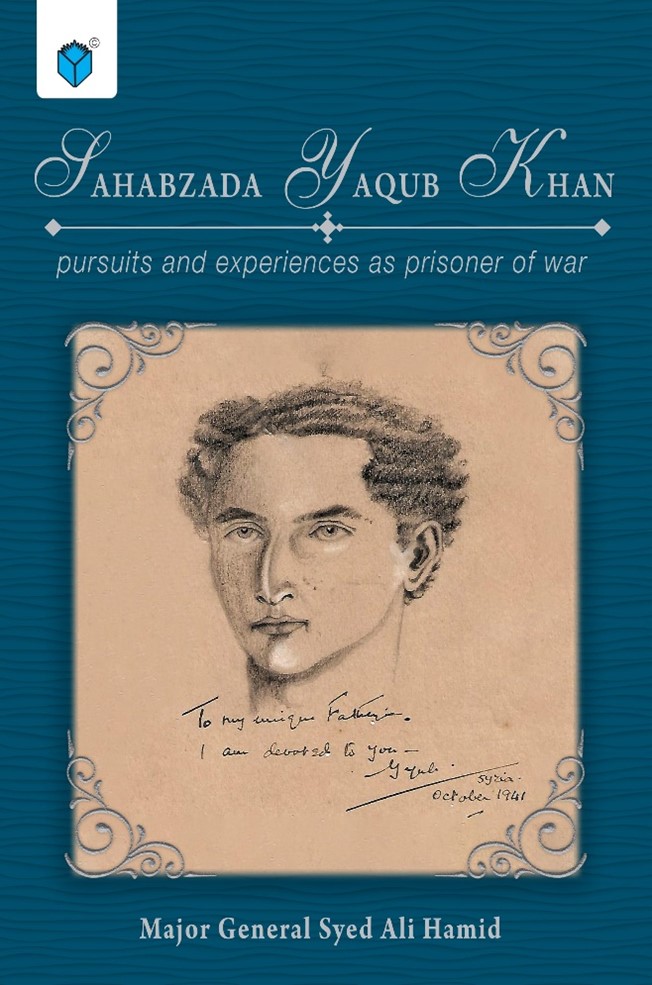

The book gives a remarkable perspective on the freedom struggle of the South Asian Subcontinent. Sahibzada Yaqub was born in 1920 when there was not a single Indian holding a commissioned rank in the Indian Army. Yet, by 1941 when he departed for Egypt, there were hundreds of young natives holding commissions of various types and serving with honour. Barely six years later, the British had departed after handing over reins of power to the leaders of the two newly created independent states.

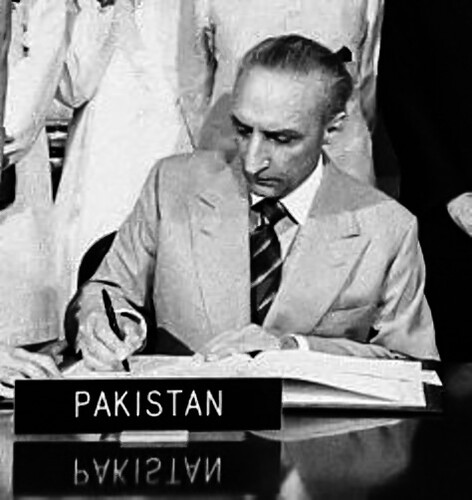

Though this book is limited to the initial four years of his service, it is now well known that as a Lt General and Commander of the Eastern Command during the last days of united Pakistan, Sahibzada Yaqub refused the order of then President General Yahya Khan to carry out military action against the people of erstwhile East Pakistan (today Bangladesh).

Apparently, Yahya Khan and Sahibzada Yaqub, as two officers of the British Indian Army, deployed in North Africa at the same time and who also became fellow POWs, had come to diametrically opposite conclusions regarding the solution to the issue of unrest in the eastern wing of the country. One only wishes that, during his captivity, Yahya, like Yaqub, had kept himself busy with studying philosophy and literature instead of wasting his time pursuing liquor. They both kept that course throughout their lives and developed into completely different men. As it turned out, the position taken by Yaqub during those fateful days of 1971 stands vindicated. He shall forever be respected by history, as opposed to his then Chief, who shall remain vilified.

There is a long tradition of soldiers becoming managers of foreign policy in their nations because of their vast studies in strategy, exposure to foreign cultures and interaction with leaders during the tenure of their service. Two prominent such names in recent times are Alexander Haig and Colin Powel, who retired as generals of the army and then served as Secretaries of State to Presidents Reagan and Bush respectively. The book under review informs us that Sahibzada Yaqub had a rich experience of travelling through a number of nations, first as a subaltern in the Allied army through the Middle East, as a POW through Europe and then in the service of Pakistan. In addition to the four European languages mentioned above, that he learnt during his captivity, he could speak also speak Urdu, English and Bengali.

The book is a remarkable endeavour as it encapsulates a difficult time in the life of a remarkable man. Had Ali Hamid not narrated this story, it is possible that this important part of our history would have been forgotten.

Although the writer mentions in the prologue that the book is primarily based on the 60 pages that Sahibzada Yaqub wrote during that last two years of his captivity and also some other secondary resources, there are no end-page or end-book references. Such references are an integral part of a non-fiction book, and a mere bibliography is not a substitute for them. For instance, the mention of Sulmona valley massacre by Germans (page 94) could have been supplemented with some details for emphasis and a reference. On page 192 too, where a British POW has been quoted for comparing German efficiency against Italian confusion, the reference is sorely missed. There are several such places in the book where references would have established authenticity of the information. Similarly, an index should also have been given.

This highly readable and absorbing book is a good addition to the history of WWII and also to the biography section of our libraries.

Subsequently, after the British East India Company (BEIC) emerged victorious in the tussle to control India, some of the Rohilla Pathans accepted the reality of British supremacy and agreed to rule under their sovereignty as their vassals. Their princely states of Bhopal, Rampur, Tonk, Malerkotla, Pataudi and a host of others were established under these terms. It is an interesting and astonishing fact that the princely Afghan rulers and their descendants transformed from pitiless fighters into the most enlightened rulers in India. They established libraries and educational institutions, encouraged art and literature, and maintained peace and order.

Rohillas are often termed as ferocious and their name has earned much notoriety because of the cruelties inflicted by Ghulam Qadir Rohilla on the Mughal household of Emperor Shah Alam II in the mid-1780s. However, they were more educated, cultured and enterprising than many Indians. Lord Macaulay was one of the most prominent writers and thinkers of early 19th century, who served on the council of the Governor General as law member between 1834 and 1838, and who was responsible for introducing western education in India. In his long essay on Governor General Warren Hastings, Macaulay wrote thus about the Rohilla Pathans, "To this day they are regarded as the best of all sepoys at the cold steel; and […] the only natives of India to whom the word "gentleman" can with perfect propriety he applied, are to be found among the Rohillas."

The above context should facilitate in understanding the persons of Sahibzada Yaqub Khan, who belonged to the royal family of the Princely State of Rampur and was a descendant of Rohilla Pathans. His ancestors had fought against the British in the second half of the 18th century. Rampur State was created in 1774 under the tutelage of the British East India Company, when Rohillas were defeated by the combined British Bengal and Awadh (Oudh) Armies. Starting with its progenitor Faizullah Khan, a son of the founder of the Rohikhand State and a direct ancestor of the Sahibzada, Rampur rulers patronised art and music. Faizullah established a library that subsequently came to be known as Raza Library, and which was one of the best endowed libraries of India – with thousands of manuscripts, paintings, documents and artefacts.

The above context should facilitate in understanding the persons of Sahibzada Yaqub Khan, who belonged to the royal family of the Princely State of Rampur and was a descendant of Rohilla Pathans. His ancestors had fought against the British in the second half of the 18th century. Rampur State was created in 1774 under the tutelage of the British East India Company, when Rohillas were defeated by the combined British Bengal and Awadh (Oudh) Armies. Starting with its progenitor Faizullah Khan, a son of the founder of the Rohikhand State and a direct ancestor of the Sahibzada, Rampur rulers patronised art and music. Faizullah established a library that subsequently came to be known as Raza Library, and which was one of the best endowed libraries of India – with thousands of manuscripts, paintings, documents and artefacts.Rampur produced many stalwarts in politics, literature and arts. It bred people like Maulana Muhammad Ali Jauhar (Khilafat Movement), Maulana Shaukat Ali Gauhar (Khilafat Movement), Abul Kalam Azad (politician, President of All India Congress), Dr Manzoor Ahmad (scientist/philosopher), Muhammad Ali (Pakistani actor), Obaidullah Baig (intellectual/TV artist), Shama Zaidi (Indian screenplay writer), Raza Murad (Indian actor), Pran (Indian actor), Athar Shah Khan Jaidi (Pakistani TV/drama) and many others. It is, therefore, no surprise that the land gave birth and raised a prodigious son like Sahibzada Yaqub, who was universally respected, first as a soldier and then as a diplomat.

As the book is based on Sahibzada Yaqub's wartime log, the reader is astonished at the details left behind by the meticulous officer: details that enabled a worthy writer like Ali Hamid to complete the history of the man and his life relating to those four years; one of which was spent in the Middle East and three as a POW in German hands

Ali Hamid, a retired major general of the Pakistan Army, served in the armoured corps, the same arm to which Sahibzada Yaqub was commissioned in 1940. He is a gifted writer and is the author of At the Forward Edge of Battle - A History of the Pakistan Armoured Corps 1938-2016 in two volumes and Forged in the Furnace of Battle: The War History of 26 Cavalry Chhamb Operations 1971. He also contributes regularly to The Friday Times – Naya Daur, the Express Tribune and many other periodicals and journals. He is one of the most appropriate writers to take up the subject of a soldier, a war and the life of a POW.

The book under review covers four crucial years of Sahibzada Yaqub’s life; from January 1941, when his regiment departed for Egypt, through May 1942 when he became a POW, till his release and arrival in London in April 1945, and his subsequent repatriation to India two months later.

During these four years, Sahibzada Yaqub lived life in top gear. He was only 22 years of age when he left India with his regiment, but underwent experiences that an ardent adventurer can only hope to achieve in a lifetime. He started his sojourn by the first sea voyage of his life and ended by his first air travel. In these years, he travelled or force-marched through several countries of the Middle East and Europe. He took part in some of the most famous battles of WW II and served with soldiers of several nationalities, was captured by ‘efficient’ Germans and detained under the ‘disorganised’ Italians, survived on meagre POW rations and then dined lavishly in the best restaurants of London when freed, wore a single uniform for weeks on end but went on to wear hand-stitched Savile Row suits, travelled in windowless cramped train carriages and then in VIP aircraft, was treated badly by his goalers and later honoured by his C-in-C. In short, the book depicts extremes of deprivation and indulgence that he experienced during those years.

As the book is based on Sahibzada Yaqub's wartime log, the reader is astonished at the details left behind by the meticulous officer: details that enabled a worthy writer like Ali Hamid to complete the history of the man and his life relating to those four years; one of which was spent in the Middle East and three as a POW in German hands.

As would be expected, the descriptions by the author of military equipment and organisation are brilliant. The following sentence, with its fine details on page 32 made pleasurable reading, "They were provided with better mobility with tracked universal carriers and better firepower with 3-inch mortars and 2-pounder anti-tank guns mounted on 6-ton trucks."

His other descriptions are equally eloquent, such as that on pages 33-34 of the Service Guide to Cairo about recreational facilities available in the city. Similarly, a description of prisoners' feelings as they waited for the US forces to release them from Oflag-79, their POW camp (page 148) is very impressive. These depictions in words are like paintings on a canvas or sketching on paper.

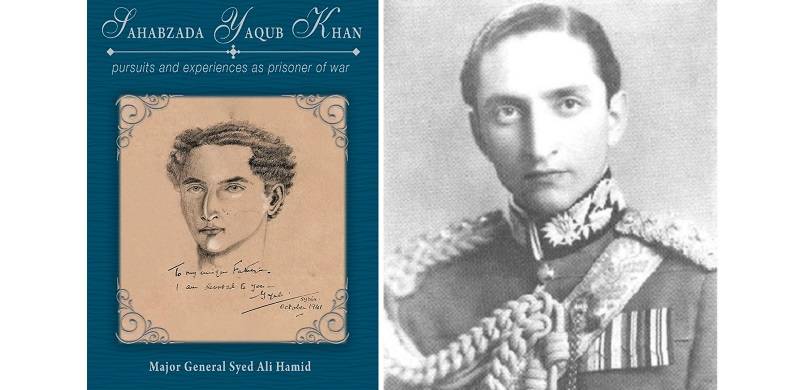

Title: Sahabzada Yaqub Khan: Pursuits and Experiences as Prisoner of War

Author: Major General Syed Ali Hamid (retd)

Publishers: Paramount Books (Pvt) Ltd, Pakistan

ISBN: 978-969-210-610-8

Pages: 213

Price: Rs 1,295/-

The experience of being a POW for a long time is physically difficult and psychologically grim. Our own POWs of the 1971 war tell stories of deprivation and hardship that are similar to the story of Sahibzada Yaqub as depicted in this book. After being made a POW by the German army, he and his fellow prisoners were handed over to the Italian forces. They had to walk through the desert without food or water. In fact, the food shortage was so acute that their Italian captors had to release all non-commissioned prisoners. The officer prisoners lived in crammed quarters and suffered through shortages of food and water. Their voyage through the Mediterranean sea in Italian cargo ships, as narrated in the book, was perilous because they were being sunk regularly by British submarines – with several hundred Allied prisoners losing their life.

Sahibzada Yaqub’s impeccable behaviour throughout his life was forged early in his career, as can be discerned in this book. His displayed courage and moral strength under incarceration. He didn't wilt in those trying circumstances. Instead, as depicted in detail by Ali Hamid, he used his forced leisure time well to become a polyglot. He learnt to speak four European languages, including German, French, Russian and Italian. It is often said that he had a knack for learning foreign languages as if his brain were endowed or wired to do so. In actual fact, it was simply his determination and hard work, along with his superior intellect, that enabled him in his mid-20s to learn all these languages. Later in life, as a diplomat, he could simultaneously carry out discussions with four different nationals in their own mother tongue.

Apparently, Yahya Khan and Sahibzada Yaqub, as two officers of the British Indian Army, deployed in North Africa at the same time and who also became fellow POWs, had come to diametrically opposite conclusions regarding the solution to the issue of unrest in the eastern wing of the country. One only wishes that, during his captivity, Yahya, like Yaqub, had kept himself busy with studying philosophy and literature instead of wasting his time pursuing liquor

The hallmark of storytelling is to pick up a small insignificant incident, event or a person and build it into an interesting readable tale without ignoring facts. Syed Ali Hamid is a natural storyteller. Several of his descriptions in the book are based on the routine life of any POW camp, but he has converted them into interesting tales. His accounts of preparation for theatre (page 73), of a concert in December 1944 at a POW camp named Oflag-79 in Brunswick (page 128} and that of Savile Row (page 166) are fascinating.

The broad perceptions of the author are evident in many parts of the book. For instance, writing about Sahibzada's drive through the Jewish-owned pleasantly green fields of northern Palestine on his regiment's recall to Egypt from Syria in February 1942, the author writes, "In some ways, it reminded him of his parents’ house in Dehradun with its fruit trees." Or this: "Sahibzada Yaqub sat in his truck and watched the sun sink into the desert sand." Clearly, these are extrapolations by the author through his own visualisation of events, which make the book an interesting read

The book gives a remarkable perspective on the freedom struggle of the South Asian Subcontinent. Sahibzada Yaqub was born in 1920 when there was not a single Indian holding a commissioned rank in the Indian Army. Yet, by 1941 when he departed for Egypt, there were hundreds of young natives holding commissions of various types and serving with honour. Barely six years later, the British had departed after handing over reins of power to the leaders of the two newly created independent states.

Though this book is limited to the initial four years of his service, it is now well known that as a Lt General and Commander of the Eastern Command during the last days of united Pakistan, Sahibzada Yaqub refused the order of then President General Yahya Khan to carry out military action against the people of erstwhile East Pakistan (today Bangladesh).

Apparently, Yahya Khan and Sahibzada Yaqub, as two officers of the British Indian Army, deployed in North Africa at the same time and who also became fellow POWs, had come to diametrically opposite conclusions regarding the solution to the issue of unrest in the eastern wing of the country. One only wishes that, during his captivity, Yahya, like Yaqub, had kept himself busy with studying philosophy and literature instead of wasting his time pursuing liquor. They both kept that course throughout their lives and developed into completely different men. As it turned out, the position taken by Yaqub during those fateful days of 1971 stands vindicated. He shall forever be respected by history, as opposed to his then Chief, who shall remain vilified.

There is a long tradition of soldiers becoming managers of foreign policy in their nations because of their vast studies in strategy, exposure to foreign cultures and interaction with leaders during the tenure of their service. Two prominent such names in recent times are Alexander Haig and Colin Powel, who retired as generals of the army and then served as Secretaries of State to Presidents Reagan and Bush respectively. The book under review informs us that Sahibzada Yaqub had a rich experience of travelling through a number of nations, first as a subaltern in the Allied army through the Middle East, as a POW through Europe and then in the service of Pakistan. In addition to the four European languages mentioned above, that he learnt during his captivity, he could speak also speak Urdu, English and Bengali.

The book is a remarkable endeavour as it encapsulates a difficult time in the life of a remarkable man. Had Ali Hamid not narrated this story, it is possible that this important part of our history would have been forgotten.

Although the writer mentions in the prologue that the book is primarily based on the 60 pages that Sahibzada Yaqub wrote during that last two years of his captivity and also some other secondary resources, there are no end-page or end-book references. Such references are an integral part of a non-fiction book, and a mere bibliography is not a substitute for them. For instance, the mention of Sulmona valley massacre by Germans (page 94) could have been supplemented with some details for emphasis and a reference. On page 192 too, where a British POW has been quoted for comparing German efficiency against Italian confusion, the reference is sorely missed. There are several such places in the book where references would have established authenticity of the information. Similarly, an index should also have been given.

This highly readable and absorbing book is a good addition to the history of WWII and also to the biography section of our libraries.