Boarding the Careem car that I had earlier booked, the Captain gave me a quizzical look and asked if I was from Karachi. I don’t know how they figured it out (my spoken Urdu accent, or how I carry myself?), but any and every human interaction had them immediately guess that I was most definitely not a Lahori. Upon affirming, he randomly asked why I would venture into Lahore’s old Walled City and that, too, on my own; this explained that initial perplexed look he gave me, whilst confirming my drop off point at Delhi Gate.

Let’s hold onto this thought for a split second and quickly go back to basics.

How do I explain to him (or anyone, for that matter), the need to escape the everyday monotony of one’s life or somebody’s pursuit of a temporary reprieve from their so-called “nine-to-five” routine? Would he have understood? Or was this a case of me attempting to #disconnecttoreconnect?

In retrospect, I wonder if I (myself) knew what I knew what I was getting into – as I travelled to Lahore, marking a visit to the Walled City a top priority.

For starters, I knew that several areas would be similar to where I was coming from in Karachi; so, I generally stayed away from the usual hubs: M.M. Alam, Gulberg and Defence.

For starters, I knew that several areas would be similar to where I was coming from in Karachi; so, I generally stayed away from the usual hubs: M.M. Alam, Gulberg and Defence.

Yes, I did have a quick dessert at Rina’s Kitchenette, dinner at Cooco’s Den and took a walk at “the backside” of the food street. I visited the very clichéd Badshahi Masjid and shopped till I dropped at Dupatta Galli at Liberty Market. But honouring my initial resolve to keep it different, I took the road less travelled to the surviving gates (from the Mughal era) in Lahore.

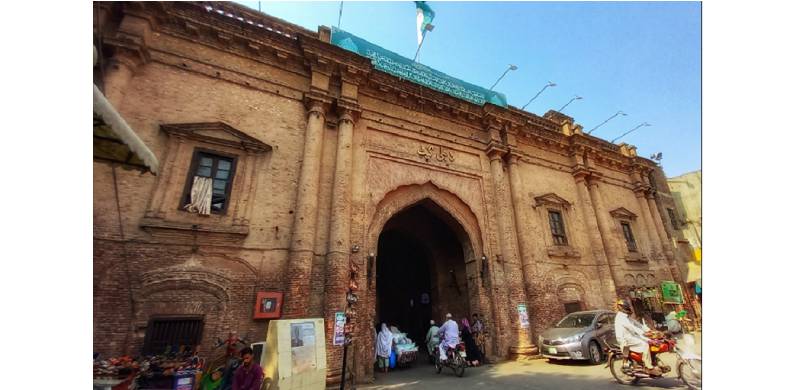

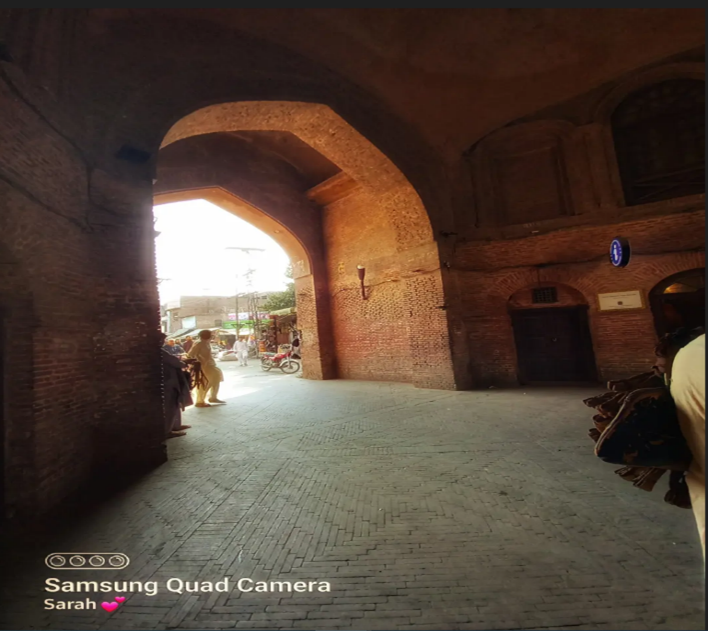

Of all the gates that I visited, Delhi Gate (locally called Delhi Darwaza) was possibly the most fascinating of all; this one gate leads in and out of the old, walled city of Lahore and is one of the few that have stood the test of times. Built by Badshah Akbar, the gate opens eastward in the direction of Delhi – hence, the name and is probably the closest we can get to Delhi, given geopolitical conditions between India and Pakistan.

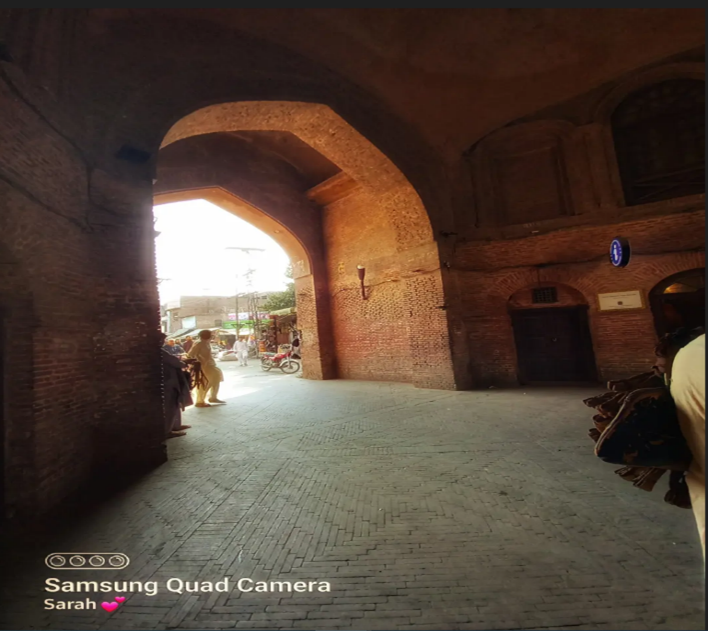

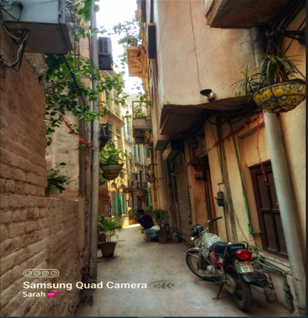

As I entered the enormous entrance, there was an energy that seemed to radiate from the bricks and the walls and the arches. And if these bricks and walls and arches could speak, there would be fables of love and glory, of war and peace, of betrayal and loyalty and a million other tales of when kings treaded these paths in all their grandeur. Walking through narrow sunlit streets and across structures that have endured harsh weathers and wars, it was not hard to imagine the magnificence of eras gone by.

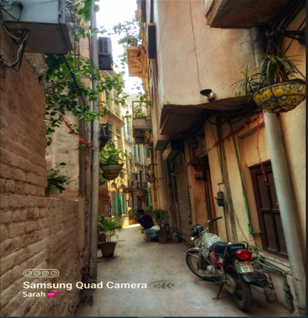

Walking through these very narrow lanes, I was told about how the (Late) Mushtaq Ahmad Yusafi described these allies:

“Androon Lahore ki chand galiyan itni tang hain ke agar ek taraf se mard aur doosri taraf se aurat guzar rahi ho to darmiyan mein sirf nikkah ki gunjaish reh jaati hai”.

(Some streets in the walled street of Lahore are extremely narrow that if from one end a man is coming and from another woman, then there is only space of Nikah between them).

Cliché as it might sound, walking across “vintage Lahore” gave the feel of literally going back in time. Despite living in the 21st century, people living within the Walled City seemed to be leading lives simpler than the remaining country and even the larger city where they resided. I was told that this difference in life pace was a typically Lahore “thing” (more so on the city outskirts), but coming from Karachi – this “thing” was a tad bit irksome. Was this just a lifestyle quality or were these people better at living in the moment? I really don’t know, but this is probably what that Careem Captain meant, when he said: “Jidhar jaa rahi hu, wo asli Lahore hai. Jahan se aapku sawaari milli, jidhar aap ruki huey hu, wo Lahore thori hai.”

Cliché as it might sound, walking across “vintage Lahore” gave the feel of literally going back in time. Despite living in the 21st century, people living within the Walled City seemed to be leading lives simpler than the remaining country and even the larger city where they resided. I was told that this difference in life pace was a typically Lahore “thing” (more so on the city outskirts), but coming from Karachi – this “thing” was a tad bit irksome. Was this just a lifestyle quality or were these people better at living in the moment? I really don’t know, but this is probably what that Careem Captain meant, when he said: “Jidhar jaa rahi hu, wo asli Lahore hai. Jahan se aapku sawaari milli, jidhar aap ruki huey hu, wo Lahore thori hai.”

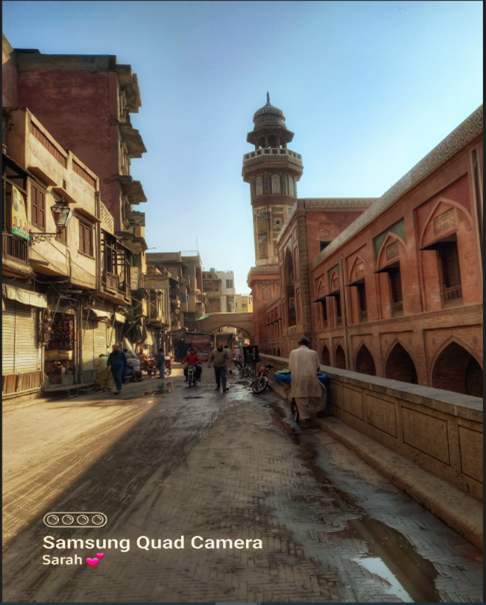

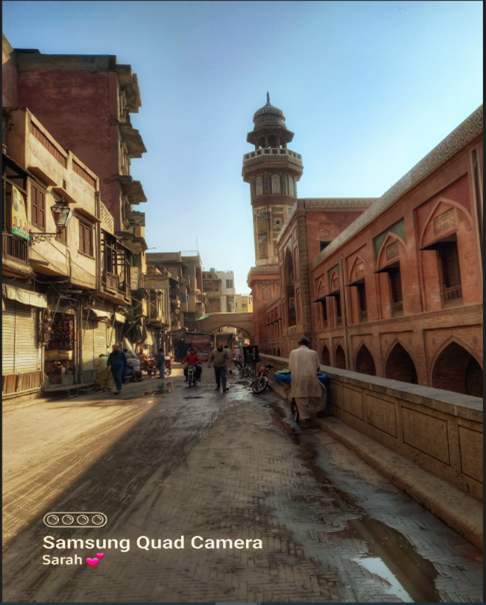

Several by-lanes across and multiple steps ahead, I somehow caught the towering minaret of the Wazir Khan Mosque calling out to me.

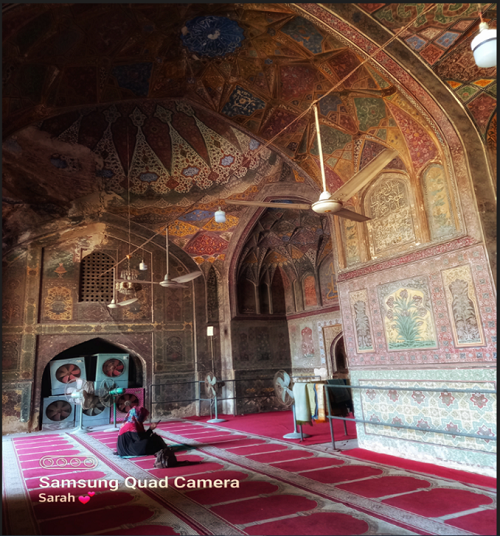

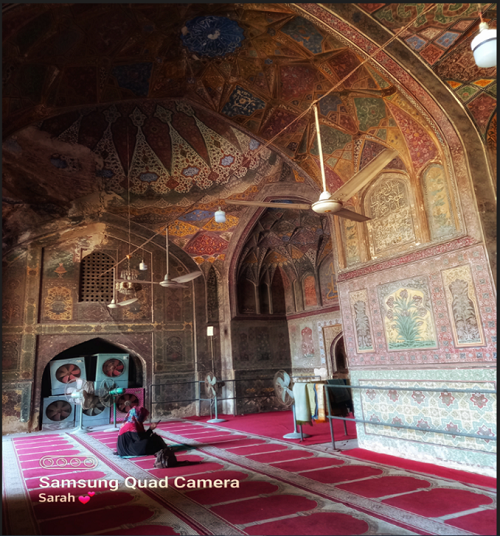

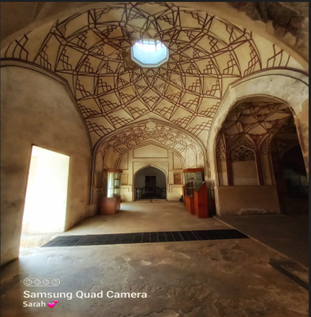

As I stepped into the courtyard, I was stunned by the complex frescoes across the walls and ceilings of the mosque. At first glance, it seemed entirely overwhelming; but a closer look shows a unique and deliberate spiritual design intention. Walking barefoot on the red stone within the courtyard towards the main prayer hall, my feet immediately felt the grooves between the stones – and I noticed the geometric patterns on the floor.

Going into the backstory of Masjid Wazir Khan, legend says that Mughal Padishah Jahangir was distressed with the untreatable illness of his beloved wife Malika Noor Jehan; physicians were warned of an ill fate if she wasn't cured, but none was allowed to physically touch her. This is when Physician Hakim Sheikh Ilmuddin Ansari, was summoned for her treatment. Ansari discovered a cyst under the empress’s foot and requested Badshah Jahangir to stand aside during the treatment process – regardless of however much unconventional and painful it might be. The Badshah agreed and Ansari instructed burning sand being spread across the fort. Malika Noor Jehan was then requested to walk on the burning sand in order to get an impression of her footprints; and then take another walk across the sand, after embedding sharp objects therein. The cyst in her foot burst and the hot sand healed the wound. As a reward, Badshah Jahangir made Ansari part of the royal court and elevated him to the position of an officer of the hospitals. Malika Noor Jehan’s recovery was celebrated across Lahore, where she presented the hakim with her own jewelry. The rest, as they say, is history. Wazir Khan continued to serve at the Mughal court as the throne later passed from Emperor Jahangir to his son Emperor Shah Jahan. And little did he know that he would continue to live on, in the form of the masjid he left after himself.

This was the extent of my knowledge as I made my way through Delhi Gate inside the Walled City towards the Masjid Wazir Khan.

This was the extent of my knowledge as I made my way through Delhi Gate inside the Walled City towards the Masjid Wazir Khan.

And rung (colour) was the first word that entered my mind as I walked through the entrance into the courtyard and gazed upon the main archway. I am fortunate to have visited numerous mosques, including the harams of Makkah, Madinah and others in Pakistan. While these harams hold their own sanctity, no “visual” reference point in my memory could compare against Masjid Wazir Khan.

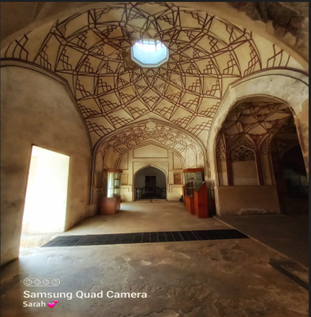

The rest of my day at Delhi Gate was spent visiting other quintessential Mughal monuments: the bazaar, Shahi Hammam, Gali Surjan Singh and Haveli Alif Shah. But despite the beauty and the historical reverence that each of these locations holds, none of them matched the tune hummed by Masjid Wazir Khan. And even as the majestic of the Badshahi Masjid envelopes you (as intended by Badshah Aurangzeb, who was obsessed with one-upping his father’s Jama Masjid in Delhi), it pales in comparison to the very humble and completely unceremonious invite extended by Masjid Wazir Khan.

And maybe this is where my quest for peace ended.

As I made my way out of the masjid, a surreal calm settled upon me – making me realise that I was looking for the proverbial “vaapsi”, loosely translated as “return”. But the vaapsi I was looking for, alluded to more than just the literal act of returning. Rather, it referred to our vaapsi to familiarity – or even a longing thereof.

But this poses questions: return to what familiarity and where?

And that is where the irony lies.

Wherever you are, let your calm overpower you and understand that that is where you belong – where your “then” and “now” meet.

Let’s hold onto this thought for a split second and quickly go back to basics.

How do I explain to him (or anyone, for that matter), the need to escape the everyday monotony of one’s life or somebody’s pursuit of a temporary reprieve from their so-called “nine-to-five” routine? Would he have understood? Or was this a case of me attempting to #disconnecttoreconnect?

In retrospect, I wonder if I (myself) knew what I knew what I was getting into – as I travelled to Lahore, marking a visit to the Walled City a top priority.

For starters, I knew that several areas would be similar to where I was coming from in Karachi; so, I generally stayed away from the usual hubs: M.M. Alam, Gulberg and Defence.

For starters, I knew that several areas would be similar to where I was coming from in Karachi; so, I generally stayed away from the usual hubs: M.M. Alam, Gulberg and Defence.Yes, I did have a quick dessert at Rina’s Kitchenette, dinner at Cooco’s Den and took a walk at “the backside” of the food street. I visited the very clichéd Badshahi Masjid and shopped till I dropped at Dupatta Galli at Liberty Market. But honouring my initial resolve to keep it different, I took the road less travelled to the surviving gates (from the Mughal era) in Lahore.

Of all the gates that I visited, Delhi Gate (locally called Delhi Darwaza) was possibly the most fascinating of all; this one gate leads in and out of the old, walled city of Lahore and is one of the few that have stood the test of times. Built by Badshah Akbar, the gate opens eastward in the direction of Delhi – hence, the name and is probably the closest we can get to Delhi, given geopolitical conditions between India and Pakistan.

As I entered the enormous entrance, there was an energy that seemed to radiate from the bricks and the walls and the arches. And if these bricks and walls and arches could speak, there would be fables of love and glory, of war and peace, of betrayal and loyalty and a million other tales of when kings treaded these paths in all their grandeur. Walking through narrow sunlit streets and across structures that have endured harsh weathers and wars, it was not hard to imagine the magnificence of eras gone by.

Walking through these very narrow lanes, I was told about how the (Late) Mushtaq Ahmad Yusafi described these allies:

“Androon Lahore ki chand galiyan itni tang hain ke agar ek taraf se mard aur doosri taraf se aurat guzar rahi ho to darmiyan mein sirf nikkah ki gunjaish reh jaati hai”.

(Some streets in the walled street of Lahore are extremely narrow that if from one end a man is coming and from another woman, then there is only space of Nikah between them).

Cliché as it might sound, walking across “vintage Lahore” gave the feel of literally going back in time. Despite living in the 21st century, people living within the Walled City seemed to be leading lives simpler than the remaining country and even the larger city where they resided. I was told that this difference in life pace was a typically Lahore “thing” (more so on the city outskirts), but coming from Karachi – this “thing” was a tad bit irksome. Was this just a lifestyle quality or were these people better at living in the moment? I really don’t know, but this is probably what that Careem Captain meant, when he said: “Jidhar jaa rahi hu, wo asli Lahore hai. Jahan se aapku sawaari milli, jidhar aap ruki huey hu, wo Lahore thori hai.”

Cliché as it might sound, walking across “vintage Lahore” gave the feel of literally going back in time. Despite living in the 21st century, people living within the Walled City seemed to be leading lives simpler than the remaining country and even the larger city where they resided. I was told that this difference in life pace was a typically Lahore “thing” (more so on the city outskirts), but coming from Karachi – this “thing” was a tad bit irksome. Was this just a lifestyle quality or were these people better at living in the moment? I really don’t know, but this is probably what that Careem Captain meant, when he said: “Jidhar jaa rahi hu, wo asli Lahore hai. Jahan se aapku sawaari milli, jidhar aap ruki huey hu, wo Lahore thori hai.”Several by-lanes across and multiple steps ahead, I somehow caught the towering minaret of the Wazir Khan Mosque calling out to me.

As I stepped into the courtyard, I was stunned by the complex frescoes across the walls and ceilings of the mosque. At first glance, it seemed entirely overwhelming; but a closer look shows a unique and deliberate spiritual design intention. Walking barefoot on the red stone within the courtyard towards the main prayer hall, my feet immediately felt the grooves between the stones – and I noticed the geometric patterns on the floor.

Going into the backstory of Masjid Wazir Khan, legend says that Mughal Padishah Jahangir was distressed with the untreatable illness of his beloved wife Malika Noor Jehan; physicians were warned of an ill fate if she wasn't cured, but none was allowed to physically touch her. This is when Physician Hakim Sheikh Ilmuddin Ansari, was summoned for her treatment. Ansari discovered a cyst under the empress’s foot and requested Badshah Jahangir to stand aside during the treatment process – regardless of however much unconventional and painful it might be. The Badshah agreed and Ansari instructed burning sand being spread across the fort. Malika Noor Jehan was then requested to walk on the burning sand in order to get an impression of her footprints; and then take another walk across the sand, after embedding sharp objects therein. The cyst in her foot burst and the hot sand healed the wound. As a reward, Badshah Jahangir made Ansari part of the royal court and elevated him to the position of an officer of the hospitals. Malika Noor Jehan’s recovery was celebrated across Lahore, where she presented the hakim with her own jewelry. The rest, as they say, is history. Wazir Khan continued to serve at the Mughal court as the throne later passed from Emperor Jahangir to his son Emperor Shah Jahan. And little did he know that he would continue to live on, in the form of the masjid he left after himself.

This was the extent of my knowledge as I made my way through Delhi Gate inside the Walled City towards the Masjid Wazir Khan.

This was the extent of my knowledge as I made my way through Delhi Gate inside the Walled City towards the Masjid Wazir Khan.And rung (colour) was the first word that entered my mind as I walked through the entrance into the courtyard and gazed upon the main archway. I am fortunate to have visited numerous mosques, including the harams of Makkah, Madinah and others in Pakistan. While these harams hold their own sanctity, no “visual” reference point in my memory could compare against Masjid Wazir Khan.

The rest of my day at Delhi Gate was spent visiting other quintessential Mughal monuments: the bazaar, Shahi Hammam, Gali Surjan Singh and Haveli Alif Shah. But despite the beauty and the historical reverence that each of these locations holds, none of them matched the tune hummed by Masjid Wazir Khan. And even as the majestic of the Badshahi Masjid envelopes you (as intended by Badshah Aurangzeb, who was obsessed with one-upping his father’s Jama Masjid in Delhi), it pales in comparison to the very humble and completely unceremonious invite extended by Masjid Wazir Khan.

And maybe this is where my quest for peace ended.

As I made my way out of the masjid, a surreal calm settled upon me – making me realise that I was looking for the proverbial “vaapsi”, loosely translated as “return”. But the vaapsi I was looking for, alluded to more than just the literal act of returning. Rather, it referred to our vaapsi to familiarity – or even a longing thereof.

But this poses questions: return to what familiarity and where?

And that is where the irony lies.

Wherever you are, let your calm overpower you and understand that that is where you belong – where your “then” and “now” meet.