(I)

An old oak tree in my neighborhood made me cry.

I live in the Oakhill area in Austin, Texas (USA), which is densely populated by hundreds of thousands of centuries-old oak trees. A testament to the fact that all civilised nations value nature as much as human life. I see the tree in the picture every day, and don't pay much attention to it.

On my regular walk today, however, as I saw the tree, my heart was filled with sorrow. All of a sudden, an old banyan tree from my childhood – about half a century ago – popped up in my memory. A tree I was deeply in love with. I still am, probably.

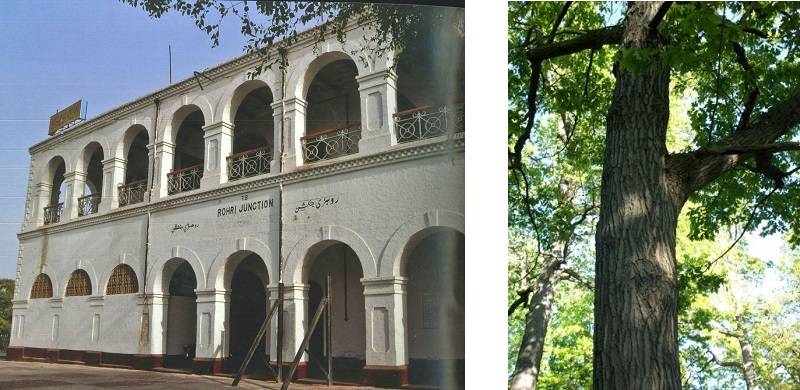

Rohri, as those who have the good fortune to be in the town know, is situated on the river Indus and the areas on both sides of the river are pretty green. However, the part of the town which I grew up in was situated on short, barren desert hills, with an occasional tree or a plant here and there.

On the most beautiful of the hills, near the railway station, the British colonialist masters – their aesthetic sense be praised! – had built the railway hospital. The hill housed some of the most ancient but still living banyan trees. The British, while building the hospital, made sure that none of the trees was harmed.

Among those trees was this one that I fell deeply in love with, in my early childhood. Almost 6 feet in diameter, it must have been hundreds of years old. It was very green with a cool shade. The planners of the hospital had the good sense to install a water fountain and a bench underneath it. Around the tree were planted fragrant shrubs.

This was one of the biggest trees I have seen in my life. To me, when I sat in the thick shade of the tree, enjoying the cool breeze on the hottest of the hot days of Rohri's sizzling summer, and enjoying the sweet fragrance of roses and jasmine, it felt like being in paradise. The breeze occasionally sprayed cool droplets of water from the fountain on my face and body, adding to the pleasure.

That tree was one of the most cherished parts of my memory.

The other day, while I was talking to my family in Sukkur on our weekly videoconference, reminiscing about the good old days in Rohri, I asked my brother about my beloved tree.

"It is long gone," my brother said.

"What do you mean by ‘It is long gone?’," perplexed, I asked.

"Do you remember the size of the tree and how valuable it was in monetary terms? Do you think it could have survived the evil eye of a corrupt officer? It was chopped to pieces and sold as wood by the Railways officers," my brother said.

A mountain of melancholy fell on me. I was speechless, dumbfounded.

As the silence drew longer, my brother, as if to console me, said "Brother, in this country where human lives have no value, do you think a tree, irrespective of how old it was or how much you loved it, would be spared because it was ancient and because you loved it? Be practical!"

The tree on my way today, reminded me of my beloved tree. My eyes were filled with tears and my heart with deep sorrow.

***

(II)

After I wrote the above lines, my friend Hasnain Shaikh reminded me of another equally old and precious tree.

About half a mile from the hospital, the British Railways had built another structure, the Railways Institute.

With high ceilings, thick brick walls, covered patios and wooden trellises for air ventilation, the grand building was commonly known as ‘Nautch Ghar’ or Dance House by the natives. The building was a kind of gymkhana club for the Railways’ British and Anglo-Indian upper staff.

When I first started visiting it as a four- to five-year-old boy with my uncles, who frequented the place to read the English, Urdu and later Sindhi dailies, or practice ping pong, the building really impressed me.

It had a large dance floor, a well-lit reading room, always crowded with people centered around a huge table reading their papers in a pin-drop silence, a library full of books – mostly Ibn-i Safi and Razia Butt novels, but books nonetheless – for the reading pleasure of railway families, and a gigantic hall for indoor badminton and ping pong matches.

Twenty years after the departure of the people for whom it was intended, the building still had an air of grandeur to it. The polish had still not faded from the big wooden dance floor, which, not used for dancing purposes anymore, even now housed a huge working piano in a corner, a few carrom boards and poker tables. The furniture was thick, old and sturdy.

The complex, that must not be less than 10 acres of land, contained green lawns, outdoor tennis courts and a play area for kids, complete with swings and slides. And, it had huge Amaltas (Golden Shower), Neem and Banyan trees.

The expansive lawns were divided in two parts by a Boxwood hedge and a movie screen frame hoisted high on iron pipes, which separated men from women. When I see the football goal-posts in my sons’ schools in Austin, I get reminded of the Nautch Ghar movie screen. Butt Sahab, a railway electrical chargeman, was given the extra charge as the projector operator. He liked old Punjabi movies and every few months, we had the pleasure of watching Sudheer, Akmal, Neelo and Fidous gyrating on musical numbers. I feel that if I could speak Punjabi somewhat fluently today, it is purely thanks to Butt Sahab and his love for cheap, old Punjabi films.

I also remember having witnessed a number of inter-city volleyball tournaments and music concerts on these lawns.

Our other ancient tree, the one that my friend Hasnain reminded me of, was situated within the Nautch Ghar complex. This neem tree was more or less the same in size as the banyan tree at the hospital. Its shade was equally soothing. Not everyone found the nerve to enjoy its cool shade, however.

You see, this magnificent tree was believed to be haunted by a “Sir Kato” – a headless ghost. A number of people swore on their child’s head to have seen him. The ones who had not seen him had heard stories about the Sir Kato from the reliable sources and firmly believed in its existence.

Throughout my childhood, I kept visiting the Nautch Ghar, on an almost daily basis, to read newspapers, play table tennis, watch movies with my friends, or talk the old, kindly librarian into lending me books. Since my father was a lawyer and not a Railways employee, I was not entitled to borrow books from the institute library.

As time passed, however, the freedom streak within us got stronger and stronger and we decided to get rid of all the relics of the days of colonial slavery. Soon after the retirement of the old librarian, books from the library started disappearing, and nobody cared. Then it was the turn of the piano and the expensive furniture. It was understood that Railways officers needed them at their bungalows more than the ordinary workers visiting the institute. Next to disappear were the projector and the ping pong table, and nobody knows who took them.

When I visited the building after a long gap, the reading room was all dark and deserted, since the railway officials found the expenditure on the newspapers unjustifiable, and nobody cared to replace the out-of-life light bulbs. The large carrom boards were taken by the deserving but unknown claimants. Maintenance of lawns was a complete waste of money and, therefore, the salaries of the gardeners found safe refuge in the rightful pockets of the people now in charge of the Nautch Ghar.

Slowly the windows and doors of the building started to vanish one by one. The wooden trellises were fine wood which fit easily into the kitchens of those who could claim it. Those who needed bricks to build rental homes and/or extra rooms alongside their quarters on the Railways land illegally, simply took them by demolishing the walls.

Our neem tree, worth hundreds of thousands of rupees easily, was completely worthless, as long as it stood there doing nothing. So, it was cut and sold to make good use of it. I am sure those who knew the art of greasing the right people’s palms must have bribed the Sir Kato as well, for when the ancient and precious tree was being killed, nobody objected – not even the most dreaded of the ghosts.

The fate of other trees was not any different.

Thus, we, the freed people, got rid of one more of the symbols of colonial vassalage.

An empty, desolate space mocks the onlooker now where once stood the grand trees and the building of Railways Institute, the Nautch Ghar.