How does one write about what can only be experienced? As a polity we have lost all empathy: this is what constantly plays in my heart’s mind. Driving towards Naseerabad and Jaffrabad in Balochistan’s southern districts, bordering Sindh, my heart contracted as I saw the debris in the Bolan River. Weaving through the Pass, remnants of the destruction what the recent rains and flash floods have wrought all around – debris of bridges, washed away roads, ancient trees. It felt like layers of humanity scattered, peeled away.

As we drove further south to our destination, the layers kept shedding. As we passed Yaro where the road dips, right into the water banks of the Bolan Riverbed, in my heart’s eye I could see the children and families wailing as they screamed for help, as the flash floods swept eight cars. No one heard nor could help. Imagine that.

Why wasn’t a bridge built? How did the relevant government authorities allow precious citizens to driver into a riverbed in the middle of the highway? This artery road connects Balochistan to Sindh!

The floods of 2022 have shown above all that Pakistanis collectively do not value their own lives. It is as simple as that. Whether you believe in God or science, both have warned us too many times in living memory to heed, build resilience, protect ourselves from climate disasters and every imaginable vulnerability. Alas, there are so many more important investments to make in the Land of the Pure.

Dasht in Mastung, I can see the standing water, where 8 precious lives were pulled out. Mud homes and how many lives perished – we will only know once the water recedes. We wait.

As I passed Picnic Point or Khajja as the locals call this date palm oasis, it reminded me of happier trips, while filming for Pakistan on a Plate.

Happy thoughts, I told myself, resilience is necessary even in the darkest times. All I could muster was how lovely the mountains looked with patches of green emerald glazed against the mud ochre mountains – my Balochistan looked green; grass dotted the arid cracked land. I smiled: the shepherds will be happy, their livestock have more feed than they could imagine since 1998. This intermittent wonder was quickly replaced by the vast cracked brown fields, as I looked closer. I realized that these are the water marks of the flash floods which washed away the mud homes, and the wild bush plants that are a source of many local medicines. 56 days of rain and waterways blocked.

The arid topography doesn’t allow the excessive rain and flash flood waters to seep down into the parched land completely. I wish it had, quenching this thirst would have been a blessing. The nature of Balochistan’s aridity can only be managed if we drill holes around the aquifers below and maintain them as they are replenished when there is water. Otherwise, the deluge of water sweeps above ground across the landscape and stands in deadly pools. Where there are no natural slopes, there are no natural drainage systems- none built since the British left.

Pakistan has not thought it wise to invest in drainage systems for Balochistan’s flash floods from our mountain’s springs, or overflows from the river (bypass canal from the Indus) or rain. Water remains a scarce resource in Balochistan and the powerful have stolen it, diverted it, abused it and now nature has provided the country and opportunity to rectify this injustice.

Pakistan has not thought it wise to invest in drainage systems for Balochistan’s flash floods from our mountain’s springs, or overflows from the river (bypass canal from the Indus) or rain. Water remains a scarce resource in Balochistan and the powerful have stolen it, diverted it, abused it and now nature has provided the country and opportunity to rectify this injustice.

Will those who make decisions in Balochistan allow investments so that we may benefit from the rainwater and stored water, and see future deluges as a blessing for all who live in Balochistan equally? I continue to live in hope.

I have never been to Sibi: the heat still greets you in mid-September. The green landscape welcomed us. This is the food basket of Balochistan, the land of banana, rice, fruit and vegetables – a source of food for Sindh, Balochistan and many parts of Pakistan.

Admiring the ploughed fields and the buffalos wading in the water pools, I was lulled into a false hope. Not so bad, I thought. Sibi hasn’t been ‘hit’ as the euphuism goes these days. But the minute we crossed into Naseerabad district, you feel it in your bones: life has changed here forever. All along the narrow highway, on both sides for as far as you can see, there is water. In an alternative universe this would be a sight for sore eyes in Balochistan. Then we saw what was floating in the dead pool – roofs of schools, gates of God knows what, and broken trees. Instinctively my senses were on guard. After all, human beings are animals, self -preservation is an instinct, right?

As we drove in, hundreds of Baloch who have escaped from this unending rain, sat in the sun. Some of these tortured fellow Pakistanis ran towards my car, hoping I had come for help. I cannot describe the shame I felt. How many could I help? 1?10?100? The need is in the millions.

So many lay sick, exhausted on the roadside on nothing but a dupatta, or a charpai in fevered stupors, some even tried to get up, but couldn’t. They did not have the energy.

The shame I felt is indescribable.

The desperation and despair were so palpable that I could not keep myself from crying. It takes some grit not to, but what are my tears worth? I am healthy, with means. And I am safe. I can just drive away to enjoy my life. What lies behind me, who will ever know or frankly care? Anywhere in the world you would call an army of ambulances and relief workers to shift these fellow citizens into shelters with medical care. Today I listened to some of them wail and cry. I tried to reassure that someone will come and help them and offered some meagre support in my capacity.

As I moved on, I visualised myself under a charpai lifted up on two of its legs, as shelter against…everything you can imagine, for a day, a week, a month. But would I last even a day?

Then I thought of the women I encountered: Saima Begum, Zahi, Dani, Ayesha, Marvi, Meera, Nado, and the endless list of fellow Pakistanis – I wish I could remember all their names – from all their villages in Naseerabad and Jaffrabad. Our people that I had met and left on the roadsides. “Where are the damned shelters?” I asked myself.

Why haven’t we organised a camp to offer shelter, after almost a month of this disaster? There is absolutely no explanation which is justifiable. None.

How long would I last without clean drinking water? I carry several bottles whenever I travel. So many here have not had a sip of clean drinking water – for how long? Some say, “Well they have lived in this abject poverty even before these insane rains and floods.”

There are some who would ease their conscience with this idea that a human being living in inhuman conditions is somehow OK. “They are not like us.” – I wonder if this is a reasonable response, for they no longer have a roof over their head, nor a corner of privacy.

Is this what we wave our flags for? Demand allegiance towards a state which provides little to its citizens? What is our social contract as Pakistanis? Forget Pakistani, how about just as a human being.

While in Naseerabad and Jaffrabad I shared my experiences on various platforms, I received phone calls from friends and new best friends, for provisions of assistance for our fellow Pakistanis. But with all our individual good will, frankly it hasn’t manifested or emerged as it did in 2010. The government’s apathy, disorganisation, lack of systems in place, are all symptoms, of a much larger malaise – we do not care about the welfare of our citizens. Will this change? Now? Can we hope? What will the signs be for this shift of conscience and actions?

Jhat Pat the old name of Jaffrabad. The bazaar is laden with vegetables and general necessities, like in most Pakistani towns. It is also filthy, with no sewerage system, green gunk streams everywhere. You can smell and see water swept through this already unplanned town. A local reporter shared how all the previous local political representatives had spent ziltch on the sewerage and garbage collection systems of the town. Health sanitation and general hygiene has never been a priority. Now this very issue will fester and magnify our water borne disease epidemic.

As I drove into Rohjan Jamali to meet displaced familes, I was keen to speak to the women. I sat with them listen to them, to let them just share their woes. There was so much crying: every fibre in my body ached.

I could not hold my tears. An elderly woman, traumatized, agitated waved her CNIC card, desperate for someone to facilitate her for BISP’s 25,000 rupees, promised by the government. I thought of all the elderly and the disabled and those who were helping them when their own loved ones are traumatised zombies in a state which is very difficult to describe.

Rohjan has a very special place in my family’s heart: the hometown of one of Balochistan’s brightest sons, Sikandar Jamali. This is not how I would have liked to come to his birthplace.

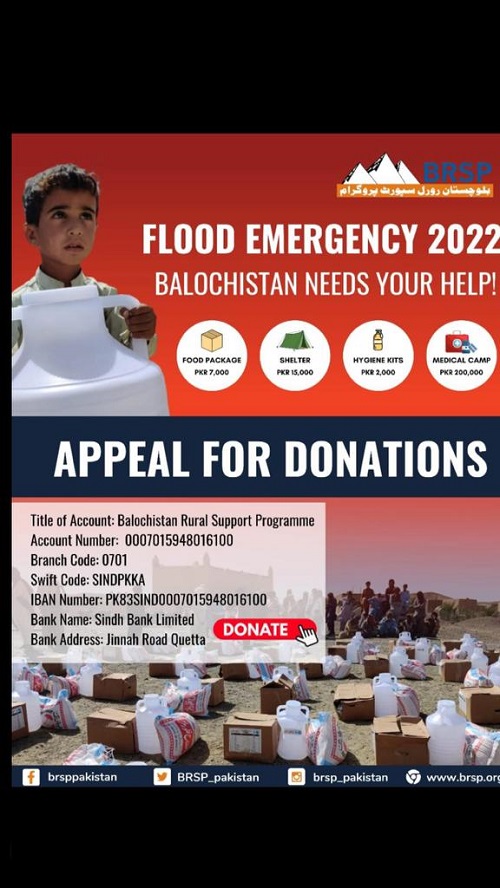

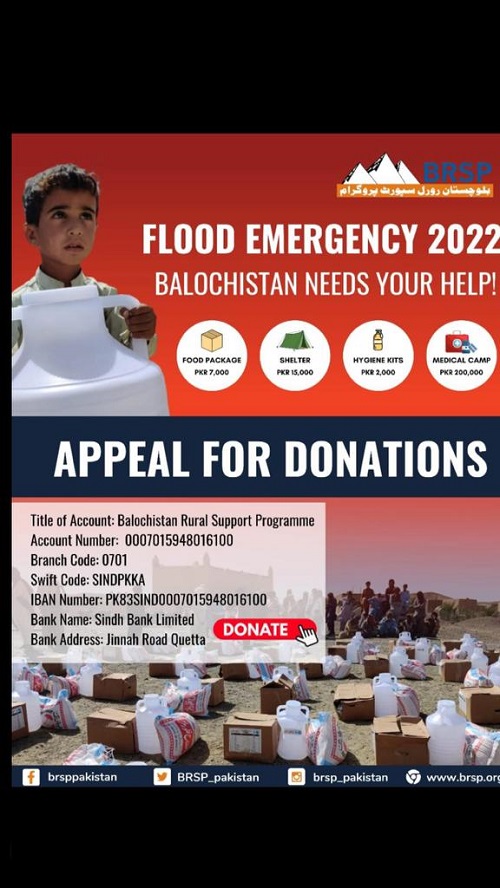

Everywhere we went, the critical need remains that of medicines for waterborne illnesses, shelter for basic human dignified existence, and food. We cannot provide roti kapra and makan at the best of times, now whatever, little they had has also been wiped out underneath their weak feet. If we do not take this opportunity to build back their lives better, we would have let them down again, and again and again.

So many of the abandoned folks that we met were from Hussainabad village in Jaffrabad and villages whose names I could not remember. But the lists are endless; I wish I had written them down for the record. The invisibility of too many parts of Balochistan hits one in so many ways and at every corner. I have a great sense of trepidation that many villages have not been rescued and without any real media or social accountability, unless one literally scouts and explores every corner of the districts, we will realise too late as to how many souls’ cries we did not hear.

On the way to Dera Allahyar so many were begging for food parcels. How much can you cry? How does a human being grieve when the tears finish?

On our way here, we had seen mountains of piled FESCO wheat bags on the roadside, in the thousands if not more: they had almost all perished because they had not been protected in the government godowns – that is one story that I was told. And some also suggested hoarding had already begun. The tragedy of the trust deficit between the public and the state is that such rumors spread like wildfire. There is very little trust that the government will provide sufficient relief. In fact, the authorities are not inclined to do so even with the spotlight on them for a while. This trust deficit can only be bridged by visible action which translates into relief for the millions at the mercy of government official support.

On our way here, we had seen mountains of piled FESCO wheat bags on the roadside, in the thousands if not more: they had almost all perished because they had not been protected in the government godowns – that is one story that I was told. And some also suggested hoarding had already begun. The tragedy of the trust deficit between the public and the state is that such rumors spread like wildfire. There is very little trust that the government will provide sufficient relief. In fact, the authorities are not inclined to do so even with the spotlight on them for a while. This trust deficit can only be bridged by visible action which translates into relief for the millions at the mercy of government official support.

Dera Murad Jamali is in Naseerabad, now a separate district like Sobatpur. This entire area is one belt, only recently split into various administrative districts. The impact of the June-July-August floods has been devastating all over. Some parts of Sobatpur remain inaccessible and have been declared by the Relief Commissioner as a Priority One area. What does this mean in real terms?

I did not get a chance to visit Jhal Magsi or Dera Bugti this time round, but I hope on the next visit in a couple of weeks, to check on the relief efforts here. It does not help when these areas have been kept remote and cut off from development agencies working in the province, prior to the floods.

If only government had been functioning for the welfare of these invisible citizens, we would not need non-governmental assistance. The Powers That Be in Pakistan must soon come to the realisation that security means human security above all.

The hardest part is walking away. As human being and in sincerity, and in empathy as equal citizens, can one walk away after merely handing over a packet of money or a bag of food, knowing fully well that I haven’t changed a thing in her life, in her most vulnerable moment?

I must live with that. Can you?

As we drove further south to our destination, the layers kept shedding. As we passed Yaro where the road dips, right into the water banks of the Bolan Riverbed, in my heart’s eye I could see the children and families wailing as they screamed for help, as the flash floods swept eight cars. No one heard nor could help. Imagine that.

Why wasn’t a bridge built? How did the relevant government authorities allow precious citizens to driver into a riverbed in the middle of the highway? This artery road connects Balochistan to Sindh!

The floods of 2022 have shown above all that Pakistanis collectively do not value their own lives. It is as simple as that. Whether you believe in God or science, both have warned us too many times in living memory to heed, build resilience, protect ourselves from climate disasters and every imaginable vulnerability. Alas, there are so many more important investments to make in the Land of the Pure.

Dasht in Mastung, I can see the standing water, where 8 precious lives were pulled out. Mud homes and how many lives perished – we will only know once the water recedes. We wait.

As I passed Picnic Point or Khajja as the locals call this date palm oasis, it reminded me of happier trips, while filming for Pakistan on a Plate.

Happy thoughts, I told myself, resilience is necessary even in the darkest times. All I could muster was how lovely the mountains looked with patches of green emerald glazed against the mud ochre mountains – my Balochistan looked green; grass dotted the arid cracked land. I smiled: the shepherds will be happy, their livestock have more feed than they could imagine since 1998. This intermittent wonder was quickly replaced by the vast cracked brown fields, as I looked closer. I realized that these are the water marks of the flash floods which washed away the mud homes, and the wild bush plants that are a source of many local medicines. 56 days of rain and waterways blocked.

The hardest part is walking away. As human being and in sincerity, and in empathy as equal citizens, can one walk away after merely handing over a packet of money or a bag of food, knowing fully well that I haven’t changed a thing in her life, in her most vulnerable moment

The arid topography doesn’t allow the excessive rain and flash flood waters to seep down into the parched land completely. I wish it had, quenching this thirst would have been a blessing. The nature of Balochistan’s aridity can only be managed if we drill holes around the aquifers below and maintain them as they are replenished when there is water. Otherwise, the deluge of water sweeps above ground across the landscape and stands in deadly pools. Where there are no natural slopes, there are no natural drainage systems- none built since the British left.

Pakistan has not thought it wise to invest in drainage systems for Balochistan’s flash floods from our mountain’s springs, or overflows from the river (bypass canal from the Indus) or rain. Water remains a scarce resource in Balochistan and the powerful have stolen it, diverted it, abused it and now nature has provided the country and opportunity to rectify this injustice.

Pakistan has not thought it wise to invest in drainage systems for Balochistan’s flash floods from our mountain’s springs, or overflows from the river (bypass canal from the Indus) or rain. Water remains a scarce resource in Balochistan and the powerful have stolen it, diverted it, abused it and now nature has provided the country and opportunity to rectify this injustice.Will those who make decisions in Balochistan allow investments so that we may benefit from the rainwater and stored water, and see future deluges as a blessing for all who live in Balochistan equally? I continue to live in hope.

I have never been to Sibi: the heat still greets you in mid-September. The green landscape welcomed us. This is the food basket of Balochistan, the land of banana, rice, fruit and vegetables – a source of food for Sindh, Balochistan and many parts of Pakistan.

Admiring the ploughed fields and the buffalos wading in the water pools, I was lulled into a false hope. Not so bad, I thought. Sibi hasn’t been ‘hit’ as the euphuism goes these days. But the minute we crossed into Naseerabad district, you feel it in your bones: life has changed here forever. All along the narrow highway, on both sides for as far as you can see, there is water. In an alternative universe this would be a sight for sore eyes in Balochistan. Then we saw what was floating in the dead pool – roofs of schools, gates of God knows what, and broken trees. Instinctively my senses were on guard. After all, human beings are animals, self -preservation is an instinct, right?

As we drove in, hundreds of Baloch who have escaped from this unending rain, sat in the sun. Some of these tortured fellow Pakistanis ran towards my car, hoping I had come for help. I cannot describe the shame I felt. How many could I help? 1?10?100? The need is in the millions.

So many lay sick, exhausted on the roadside on nothing but a dupatta, or a charpai in fevered stupors, some even tried to get up, but couldn’t. They did not have the energy.

The shame I felt is indescribable.

The desperation and despair were so palpable that I could not keep myself from crying. It takes some grit not to, but what are my tears worth? I am healthy, with means. And I am safe. I can just drive away to enjoy my life. What lies behind me, who will ever know or frankly care? Anywhere in the world you would call an army of ambulances and relief workers to shift these fellow citizens into shelters with medical care. Today I listened to some of them wail and cry. I tried to reassure that someone will come and help them and offered some meagre support in my capacity.

As I moved on, I visualised myself under a charpai lifted up on two of its legs, as shelter against…everything you can imagine, for a day, a week, a month. But would I last even a day?

Then I thought of the women I encountered: Saima Begum, Zahi, Dani, Ayesha, Marvi, Meera, Nado, and the endless list of fellow Pakistanis – I wish I could remember all their names – from all their villages in Naseerabad and Jaffrabad. Our people that I had met and left on the roadsides. “Where are the damned shelters?” I asked myself.

Why haven’t we organised a camp to offer shelter, after almost a month of this disaster? There is absolutely no explanation which is justifiable. None.

How long would I last without clean drinking water? I carry several bottles whenever I travel. So many here have not had a sip of clean drinking water – for how long? Some say, “Well they have lived in this abject poverty even before these insane rains and floods.”

There are some who would ease their conscience with this idea that a human being living in inhuman conditions is somehow OK. “They are not like us.” – I wonder if this is a reasonable response, for they no longer have a roof over their head, nor a corner of privacy.

Is this what we wave our flags for? Demand allegiance towards a state which provides little to its citizens? What is our social contract as Pakistanis? Forget Pakistani, how about just as a human being.

While in Naseerabad and Jaffrabad I shared my experiences on various platforms, I received phone calls from friends and new best friends, for provisions of assistance for our fellow Pakistanis. But with all our individual good will, frankly it hasn’t manifested or emerged as it did in 2010. The government’s apathy, disorganisation, lack of systems in place, are all symptoms, of a much larger malaise – we do not care about the welfare of our citizens. Will this change? Now? Can we hope? What will the signs be for this shift of conscience and actions?

Jhat Pat the old name of Jaffrabad. The bazaar is laden with vegetables and general necessities, like in most Pakistani towns. It is also filthy, with no sewerage system, green gunk streams everywhere. You can smell and see water swept through this already unplanned town. A local reporter shared how all the previous local political representatives had spent ziltch on the sewerage and garbage collection systems of the town. Health sanitation and general hygiene has never been a priority. Now this very issue will fester and magnify our water borne disease epidemic.

As I drove into Rohjan Jamali to meet displaced familes, I was keen to speak to the women. I sat with them listen to them, to let them just share their woes. There was so much crying: every fibre in my body ached.

I could not hold my tears. An elderly woman, traumatized, agitated waved her CNIC card, desperate for someone to facilitate her for BISP’s 25,000 rupees, promised by the government. I thought of all the elderly and the disabled and those who were helping them when their own loved ones are traumatised zombies in a state which is very difficult to describe.

Rohjan has a very special place in my family’s heart: the hometown of one of Balochistan’s brightest sons, Sikandar Jamali. This is not how I would have liked to come to his birthplace.

Everywhere we went, the critical need remains that of medicines for waterborne illnesses, shelter for basic human dignified existence, and food. We cannot provide roti kapra and makan at the best of times, now whatever, little they had has also been wiped out underneath their weak feet. If we do not take this opportunity to build back their lives better, we would have let them down again, and again and again.

So many of the abandoned folks that we met were from Hussainabad village in Jaffrabad and villages whose names I could not remember. But the lists are endless; I wish I had written them down for the record. The invisibility of too many parts of Balochistan hits one in so many ways and at every corner. I have a great sense of trepidation that many villages have not been rescued and without any real media or social accountability, unless one literally scouts and explores every corner of the districts, we will realise too late as to how many souls’ cries we did not hear.

On the way to Dera Allahyar so many were begging for food parcels. How much can you cry? How does a human being grieve when the tears finish?

On our way here, we had seen mountains of piled FESCO wheat bags on the roadside, in the thousands if not more: they had almost all perished because they had not been protected in the government godowns – that is one story that I was told. And some also suggested hoarding had already begun. The tragedy of the trust deficit between the public and the state is that such rumors spread like wildfire. There is very little trust that the government will provide sufficient relief. In fact, the authorities are not inclined to do so even with the spotlight on them for a while. This trust deficit can only be bridged by visible action which translates into relief for the millions at the mercy of government official support.

On our way here, we had seen mountains of piled FESCO wheat bags on the roadside, in the thousands if not more: they had almost all perished because they had not been protected in the government godowns – that is one story that I was told. And some also suggested hoarding had already begun. The tragedy of the trust deficit between the public and the state is that such rumors spread like wildfire. There is very little trust that the government will provide sufficient relief. In fact, the authorities are not inclined to do so even with the spotlight on them for a while. This trust deficit can only be bridged by visible action which translates into relief for the millions at the mercy of government official support.Dera Murad Jamali is in Naseerabad, now a separate district like Sobatpur. This entire area is one belt, only recently split into various administrative districts. The impact of the June-July-August floods has been devastating all over. Some parts of Sobatpur remain inaccessible and have been declared by the Relief Commissioner as a Priority One area. What does this mean in real terms?

I did not get a chance to visit Jhal Magsi or Dera Bugti this time round, but I hope on the next visit in a couple of weeks, to check on the relief efforts here. It does not help when these areas have been kept remote and cut off from development agencies working in the province, prior to the floods.

If only government had been functioning for the welfare of these invisible citizens, we would not need non-governmental assistance. The Powers That Be in Pakistan must soon come to the realisation that security means human security above all.

The hardest part is walking away. As human being and in sincerity, and in empathy as equal citizens, can one walk away after merely handing over a packet of money or a bag of food, knowing fully well that I haven’t changed a thing in her life, in her most vulnerable moment?

I must live with that. Can you?