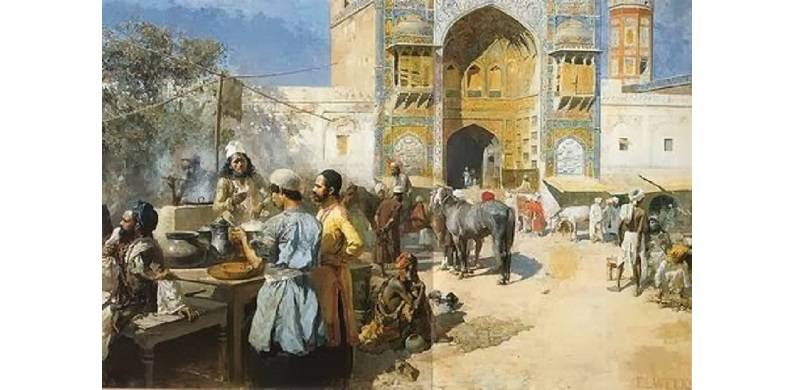

One of the prime examples of history being moulded and misinterpreted in order to provide political justifications is the historiography of pre-colonial India, especially the Mughal Empire. The fanaticism of 19th-century European sociologists and historians in upholding the concept of oriental despotism led to an explanation of pre-colonial India as a primitive and undynamic society. The Mughal Empire was represented as Muslim foreign rulers with exploitative intentions toward the Subcontinent. This representation allowed the British to justify the colonial occupation in the Subcontinent as the White Man’s Burden to modernise the “backward society” of the pre-colonial Subcontinent and created the Hindu-Muslim divide, where the Mughals were ideological heroes for Muslims and foreign invaders for Hindus.

A Muslim empire or an empire with Muslim rulers?

A common misconception about the Mughal Empire is that it was a “Muslim Empire” where a stringent Islamic ideology was followed, and the interests of Hindus were undermined. This narrative extends from the British Raj all the way to BJP. However, although Mughal Empire was an Empire in which the rulers were Muslims, the majority of their subjects consisted of non-Muslims. By and large, these regimes did not have a religious affiliation, and loyalty was defined by active participation in state matters. The reign of Akbar was the highest point of the Mughal empire, and as a ruler, Akbar was aware of the fact that he was ruling a population whose majority was non-Muslim. Hence, he devised a separate code of conduct for non-Muslims and their offenders were tried in the courts based on their own religious rulings.

“The Ibadatkhana or place of worship in Akbar’s red sandstone capital at Fatehpur Sikri became the venue for free and lively theological and philosophical debates attended by Muslims, Hindus, Zoroastrians, Jains, Jesuit Christians and Jews.” (Bose and Jalal, 1998)

A commonly used argument by Orientalist scholars and Hindu nationalists is that Hindu practices were repressed under these Muslim regimes. However, recent studies have found that the institution of social organization and new patterns of Vaishnavite and Shaivite worship originated in these regimes. And there has been no evidence of mass conversion to Islam during the Mughal period. The characterization of the Mughal empire as “foreign” itself is also based on a rather new understanding of modern nation-states. Although the empire was founded by people from outside, most of the rulers of the Mughal Empire were born in India.

Aurangzeb: a non-progressive fundamentalist or just a misunderstood emperor?

Aurangzeb who is one of the most misunderstood personalities amongst the Mughal emperors and is known for “reactionary policies”, was dependent on his non-Muslim subjects.

“More than a quarter of the mansab holders along with his leading general were Hindus.” (Metcalf, 2006)

The majority of the battles that Aurangzeb fought were against Muslims, and the notorious imposition of jizya was an action motivated by the need to fund the expensive battles rather than the intention to impose Muslim laws on non-Muslims.

As per the earlier historiography, the Mughal empire allegedly extracted large amounts of revenues from the agrarian sector of the Subcontinent. However, the Mughal Empire did not have any centralised or systematic administration to pump out revenues from the Subcontinent unlike their successors: the colonial masters. The Mughal emperor would mainly negotiate with the zamindars and the agricultural surplus was distributed among the layers of appropriate locals. In fact, the rebellions after the death of Aurangzeb which are often regarded as peasant rebellions due to the oppressive conditions under the Mughal Empire were zamindar-led rebellions, not due to economic decay but in order to gain more power.

Was pre-colonial India feally pre-modern?

The practice of referring to pre-colonial India as pre-modern India has also prevailed for a long time. This has led to a common belief that the empires which operated before colonialism were stagnant, primitive and easily pulverised. However, this belief is challenged by recent research and historians now prefer to refer to it as early-modern India. Even though the empire was mainly agrarian, it still had strong links to oceanic trade.

“From the mid-seventeenth century onwards, the empire became more heavily engaged with the international economy and may have turned more mercantilist in character, relying for its economic viability as much on textile exports as on land revenues.” (Bose and Jalal, 1998)

Moreover, the Mughals were not heavily dependent on these merchant groups for state financing: they had functional banking systems which would provide them with insurance and credit facilities. Far from being stagnant, Mughal India in the sixteenth to the seventeenth century was a metropolitan magnet of wealth and had a wide range of economic and political flexibility.

Does decentralization of power translate to a decaying society?

Another misconception of 19th-century scholarship was that the decentralised nature of the empires of pre-modern India caused social and economic decay. The Mughal empire was a loose hegemony. This loose hegemony granted localities their autonomy and as a result, experienced an economic boom.

The eighteenth century was an era of fission and renegotiation, and so the peripheries of the Mughal Empire became centralised regional powers. This strengthened the groups that were products of social mobility and change. Power shifted to lower levels of sovereignty and these small, centralised authorities were financed by banks and merchants. The agrarian surplus flourished with the adoption of new techniques and commercialisation.

Point of departure

The empires of pre-colonial India, especially the Mughal Empire, did not receive the nuanced historiography they deserved. It is a common belief that the Mughal Empire decayed into a lazy, luxury-loving, and non-progressive empire causing the decay of the Subcontinent’s social and economic fabric. This narrative only justifies the violent colonial takeover of the subcontinent.

And so, the question remains, did pre-colonial India need the saving of a white man, or do the post-colonial nation states have a lot to learn from the political and economic infrastructure of the Mughal Empire?

A Muslim empire or an empire with Muslim rulers?

A common misconception about the Mughal Empire is that it was a “Muslim Empire” where a stringent Islamic ideology was followed, and the interests of Hindus were undermined. This narrative extends from the British Raj all the way to BJP. However, although Mughal Empire was an Empire in which the rulers were Muslims, the majority of their subjects consisted of non-Muslims. By and large, these regimes did not have a religious affiliation, and loyalty was defined by active participation in state matters. The reign of Akbar was the highest point of the Mughal empire, and as a ruler, Akbar was aware of the fact that he was ruling a population whose majority was non-Muslim. Hence, he devised a separate code of conduct for non-Muslims and their offenders were tried in the courts based on their own religious rulings.

“The Ibadatkhana or place of worship in Akbar’s red sandstone capital at Fatehpur Sikri became the venue for free and lively theological and philosophical debates attended by Muslims, Hindus, Zoroastrians, Jains, Jesuit Christians and Jews.” (Bose and Jalal, 1998)

A commonly used argument by Orientalist scholars and Hindu nationalists is that Hindu practices were repressed under these Muslim regimes. However, recent studies have found that the institution of social organization and new patterns of Vaishnavite and Shaivite worship originated in these regimes. And there has been no evidence of mass conversion to Islam during the Mughal period. The characterization of the Mughal empire as “foreign” itself is also based on a rather new understanding of modern nation-states. Although the empire was founded by people from outside, most of the rulers of the Mughal Empire were born in India.

The 18th century was an era of fission and renegotiation, and so the peripheries of the Mughal Empire became centralised regional powers. This strengthened the groups that were products of social mobility and change. Power shifted to lower levels of sovereignty

Aurangzeb: a non-progressive fundamentalist or just a misunderstood emperor?

Aurangzeb who is one of the most misunderstood personalities amongst the Mughal emperors and is known for “reactionary policies”, was dependent on his non-Muslim subjects.

“More than a quarter of the mansab holders along with his leading general were Hindus.” (Metcalf, 2006)

The majority of the battles that Aurangzeb fought were against Muslims, and the notorious imposition of jizya was an action motivated by the need to fund the expensive battles rather than the intention to impose Muslim laws on non-Muslims.

As per the earlier historiography, the Mughal empire allegedly extracted large amounts of revenues from the agrarian sector of the Subcontinent. However, the Mughal Empire did not have any centralised or systematic administration to pump out revenues from the Subcontinent unlike their successors: the colonial masters. The Mughal emperor would mainly negotiate with the zamindars and the agricultural surplus was distributed among the layers of appropriate locals. In fact, the rebellions after the death of Aurangzeb which are often regarded as peasant rebellions due to the oppressive conditions under the Mughal Empire were zamindar-led rebellions, not due to economic decay but in order to gain more power.

Was pre-colonial India feally pre-modern?

The practice of referring to pre-colonial India as pre-modern India has also prevailed for a long time. This has led to a common belief that the empires which operated before colonialism were stagnant, primitive and easily pulverised. However, this belief is challenged by recent research and historians now prefer to refer to it as early-modern India. Even though the empire was mainly agrarian, it still had strong links to oceanic trade.

“From the mid-seventeenth century onwards, the empire became more heavily engaged with the international economy and may have turned more mercantilist in character, relying for its economic viability as much on textile exports as on land revenues.” (Bose and Jalal, 1998)

Moreover, the Mughals were not heavily dependent on these merchant groups for state financing: they had functional banking systems which would provide them with insurance and credit facilities. Far from being stagnant, Mughal India in the sixteenth to the seventeenth century was a metropolitan magnet of wealth and had a wide range of economic and political flexibility.

Does decentralization of power translate to a decaying society?

Another misconception of 19th-century scholarship was that the decentralised nature of the empires of pre-modern India caused social and economic decay. The Mughal empire was a loose hegemony. This loose hegemony granted localities their autonomy and as a result, experienced an economic boom.

The eighteenth century was an era of fission and renegotiation, and so the peripheries of the Mughal Empire became centralised regional powers. This strengthened the groups that were products of social mobility and change. Power shifted to lower levels of sovereignty and these small, centralised authorities were financed by banks and merchants. The agrarian surplus flourished with the adoption of new techniques and commercialisation.

Point of departure

The empires of pre-colonial India, especially the Mughal Empire, did not receive the nuanced historiography they deserved. It is a common belief that the Mughal Empire decayed into a lazy, luxury-loving, and non-progressive empire causing the decay of the Subcontinent’s social and economic fabric. This narrative only justifies the violent colonial takeover of the subcontinent.

And so, the question remains, did pre-colonial India need the saving of a white man, or do the post-colonial nation states have a lot to learn from the political and economic infrastructure of the Mughal Empire?