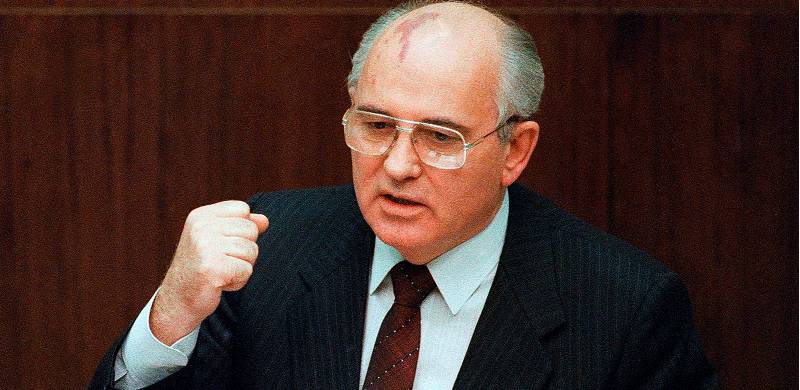

Mikhail Gorbachev, who ended the Cold War and was the last leader of the Soviet Union, died at the age of 91 in Moscow on 30 August 2020. Gorbachev led the Soviet Union from 1985 until its collapse in 1991.

The dissolution of the Soviet bloc — marked by Gorbachev’s resignation that year — ended the Cold War and years of confrontation between East and West, freed Eastern European nations from Soviet domination, and established the modern Russian state. Gorbachev won the 1990 Nobel Peace Prize for his role in ending the Cold War, but many in Russia see him as responsible for the collapse of the Soviet Union and the social and economic crises that enveloped the country in the early 1990s. He never wanted to dismantle the system, but glasnost and perestroika unleashed forces that proved impossible to control with calls for independence in the Baltic States and other parts of the Soviet Union as well as in Eastern Europe. “It is hard to think of a single person who altered the course of history more in a positive direction than Gorbachev”, Michael McFaul, a political analyst and former US ambassador in Moscow, wrote on Twitter. “Gorbachev was an idealist who believed in the power of ideas and individuals. We should learn from his legacy”

“I like Mr. Gorbachev, we can do business together” –coming from Mrs. Margaret Thatcher the former British Prime Minister this remark is quite a compliment. The occasion was the visit of the Soviet delegation led by Mr. Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev to the UK in 1984. Where his style, sophistication, sense of humour, aided by his polite and chic wife made him the darling of Fleet Street and an instant celebrity.

Mikhail Gorbachev was born on 2 March 1931. His birthplace was the fertile agricultural area of south Russia, north of the Caucasus mountains in a small village called Privolnoye, and his house located in the Stavropol district, a small single-storey brick cottage with a small kitchen, three modest rooms and a pleasant garden.

Almost nothing is known about his childhood days except that his parents were peasants. Russia in those days was in the ruthless grip of Marshal Joseph Stalin. In 1942 young Mikhail’s world went up in flames when the goose-stepping soldiers of the Third Reich occupied Stavropol. Eleven-year-old Misha as he was called, became witness to one of the greatest dramas in the history of war and conflict that is Adolf Hitler’s “Operation Barbarossa,” the German invasion of the USSR in WW2.

At the age of eleven he joined a state-owned collective farm. On this agricultural farm he worked as an agricultural worker doing all sorts of petty jobs, working in the fields and workshops as a machine operator and mechanic. During the next four years, he gained a rich and varied experience in all fields of agricultural management. From the level of field worker to farm manager under strict regimentation of state-owned land, all major policy decisions being dictated from Moscow.

In 1950, Gorbachev entered the Law School at Moscow State University, where he was not known as a very bright student. According to one former class fellow, “He was only an average student who did not have many original ideas, but he tried to be every body’s friend.” Gorbachev was more interested in politics than his studies because the legal profession was least rewarding in the Soviet Union. It could, however, be used as a stepping stone for a career in politics. His years in law school were mundane and uneventful, except that he joined the Communist party in 1952. While still a student he met fellow student Raisa Maksimovyna. Young Raisa was bright, intelligent, charming and graceful. They fell in love and were married in 1954. Raisa had a PhD degree and taught at the Moscow State University. They had two daughters but only one daughter appeared in public. The latter is called Irina: she is a doctor and the mother of their only grandchild called Oksana. Raisa Gorbachev was not only charming, poised, graceful and sophisticated but also extremely well read, with a mind of her own. She believed in expressing her opinion loud and clear, much to the resentment of many Soviet citizens.

By 1955, Nikita Khrushchev had taken over and the terror and fear of the Stalin regime was fast fading. Gorbachev had been very critical of Stalin’s oppressive and brutal methods, even during the time of Stalin’s rule in the USSR. This was before Stalin and his rule of terror were denounced by Khrushchev at the 20th Communist Party congress in 1956. Nothing definite can be said about Gorbachev’s political orientation at this stage, as glasnost unfortunately does not extend to the personal life of its author. Michael Tatu, a well-known French writer on Soviet affairs and the author of a biography on Gorbachev, has claimed that Gorbachev took an active part and played a leading role in the last purge launched by Joseph Stalin shortly before his death in 1953. This purge has been described by some as an anti-Semitic one.

The next 23 years of Gorbachev’s life were spent in the Stavropol area. He had already joined the Young Communist League or the Komsomol even before leaving his native village. He now put his heart and soul in his work for the Komsomol and from 1956 to 1958 worked as first secretary Stavropol city Komsomol organization. For the next four years he continued to work for the Komsomol: first as propaganda chief, then second secretary and finally as chief secretary. In 1963 Gorbachev was made chief of the agricultural department for the entire region of Stavropol, remarkable achievement for one so young as Gorbachev was only 32 years of age.

Gorbachev’s career took a sudden upward turn when he was appointed First Secretary of the Communist Party committee for the city of Stavropol in September 1966, later to become second secretary of the Stavropol territory party committee in August 1969. At the age of 39 he became First Secretary in April 1970, standing out as the youngest among the provincial chiefs in the whole of the USSR. One redeeming feature of his rule was that unlike other Russian rulers he remained open and accessible to anyone with a genuine complaint or grievance. As a matter of habit or policy, he always walked to his office on Lenin Square and any citizen was free to approach him instead of making an appointment to see him in his office. Boredom and monotony of rural life was broken when the Gorbachevs took foreign trips as members of state delegations. Their first trip to Western Europe was in 1966 when they rented a small car and travelled extensively through France and Italy.

Gorbachev’s hard work and dedication was finally noticed, appreciated and rewarded by the party high command in Moscow when he was elevated to the post of Deputy to the formal legislative body of the USSR in 1970 and given charge of the conservation and youth affairs commission, of which he became chairman in 1970 and along the way he was also named as the member of the all-powerful central committee in 1971. In the mysterious world of Kremlin politics talent, honesty and dedication were not the only criteria needed to climb the ladder of success: having powerful and influential mentors mattered more. Gorbachev was extremely lucky to be counted as the protégé of Mikhail Suslov, a former provincial party chief very close to Leonid Brezhnev – a man who was also the ideology minister in the Breznev cabinet. Suslov’s pressure group in the Kremlin included KGB chairman Yuri Andropov and the agricultural secretary Fyodor Kulakov. These three put together were the most powerful, formidable and influential trio in the high command of the Supreme Soviet.

Fyodor Kulakov died suddenly in 1978 and the post of communist party central secretary for agriculture fell vacant. To fill the post, Brezhnev chose Gorbachev obviously on the backing and strong recommendations of both Suslov and Andropov. Leonid Brezhnev had met Gorbachev only once briefly and this meeting had taken place at a small and remote railway station on 19 September 1978.

At the relatively young age of 47, Gorbachev became a member of the top national hierarchy and was given charge of the most troublesome area of the Soviet economy. This was a most difficult and daunting task, as agriculture had been widely recognised as the Achilles Heel of the entire Soviet System. Brezhnev’s health was fast failing and his 18-year-long regime was a cesspool of corruption and stagnation. Gorbachev in spite of all good intentions and hard work suffered one misfortune after another. There were a series of crop failures attributable to climate and a corrupt and inefficient bureaucratic system. Grain production came down from 230 million tons in 1978 to 155 million tons in 1981 and the situation reached a point when the government had to stop the publication of agricultural statistics. Billions of dollars were spent to purchase food grains from abroad.

Surprisingly, Gorbachav’s career did not suffer as a result of this fiasco. His rise continued and he was appointed a nonvoting member of the Politburo in November 1979, becoming a full member in October 1980. At the age of 49, he was the youngest member of the Politburo: 8 years younger than the next youngest member and 21 years younger than the average age of Politburo members.

Aging and almost totally senile Brezhnev died in 1982 and Gorbachev’s mentor Yuri Andropov became the Secretary General. Immediately after taking charge the simple, honest and austere Andropov started a series of revolutionary and far-reaching reforms in all spheres of Soviet society, including the purge of corrupt and incompetent party officials. Andropov’s failing health now forced him to rely more and more on his protégé Gorbachev who now became the mainstay and also liaised with the party hierarchy and foreign leaders. In 1984 Gorbachev was also named the chairman of the powerful foreign relations committee. He publicly called the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan a “grave mistake” and the war “a bleeding wound” but he always defended the Soviet Afghan policy.

Andropov’s life was cut short by kidney failure in early 1984. Kremlin watchers had already guessed Gorbachev as successor of his mentor, but this was not to be as the old guard of the Kremlin rallied to elect 72-year-old Chernenko as the new secretary general. Gorbachev went along awaiting his turn possibly even when making the nomination speech. Chernenko was so sick and infirm that during his short one-year reign that it was Gorbachev who managed all the affairs of state.

Immediately after the death of Chernenko, a fierce but brief power struggle ensued. Gorbechev’s main rival was Gregory Romanov, but he had to bow before the inevitable. In the emergency meeting of the Central Committee on 11 March 1985 just a few hours after Chernenko’s death, Gorbachev was elected Secretary General and the supreme ruler of the USSR – ironically to preside over the disintegration of his country.

The dissolution of the Soviet bloc — marked by Gorbachev’s resignation that year — ended the Cold War and years of confrontation between East and West, freed Eastern European nations from Soviet domination, and established the modern Russian state. Gorbachev won the 1990 Nobel Peace Prize for his role in ending the Cold War, but many in Russia see him as responsible for the collapse of the Soviet Union and the social and economic crises that enveloped the country in the early 1990s. He never wanted to dismantle the system, but glasnost and perestroika unleashed forces that proved impossible to control with calls for independence in the Baltic States and other parts of the Soviet Union as well as in Eastern Europe. “It is hard to think of a single person who altered the course of history more in a positive direction than Gorbachev”, Michael McFaul, a political analyst and former US ambassador in Moscow, wrote on Twitter. “Gorbachev was an idealist who believed in the power of ideas and individuals. We should learn from his legacy”

“I like Mr. Gorbachev, we can do business together” –coming from Mrs. Margaret Thatcher the former British Prime Minister this remark is quite a compliment. The occasion was the visit of the Soviet delegation led by Mr. Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev to the UK in 1984. Where his style, sophistication, sense of humour, aided by his polite and chic wife made him the darling of Fleet Street and an instant celebrity.

Mikhail Gorbachev was born on 2 March 1931. His birthplace was the fertile agricultural area of south Russia, north of the Caucasus mountains in a small village called Privolnoye, and his house located in the Stavropol district, a small single-storey brick cottage with a small kitchen, three modest rooms and a pleasant garden.

Almost nothing is known about his childhood days except that his parents were peasants. Russia in those days was in the ruthless grip of Marshal Joseph Stalin. In 1942 young Mikhail’s world went up in flames when the goose-stepping soldiers of the Third Reich occupied Stavropol. Eleven-year-old Misha as he was called, became witness to one of the greatest dramas in the history of war and conflict that is Adolf Hitler’s “Operation Barbarossa,” the German invasion of the USSR in WW2.

At the age of eleven he joined a state-owned collective farm. On this agricultural farm he worked as an agricultural worker doing all sorts of petty jobs, working in the fields and workshops as a machine operator and mechanic. During the next four years, he gained a rich and varied experience in all fields of agricultural management. From the level of field worker to farm manager under strict regimentation of state-owned land, all major policy decisions being dictated from Moscow.

In 1950, Gorbachev entered the Law School at Moscow State University, where he was not known as a very bright student. According to one former class fellow, “He was only an average student who did not have many original ideas, but he tried to be every body’s friend.” Gorbachev was more interested in politics than his studies because the legal profession was least rewarding in the Soviet Union. It could, however, be used as a stepping stone for a career in politics. His years in law school were mundane and uneventful, except that he joined the Communist party in 1952. While still a student he met fellow student Raisa Maksimovyna. Young Raisa was bright, intelligent, charming and graceful. They fell in love and were married in 1954. Raisa had a PhD degree and taught at the Moscow State University. They had two daughters but only one daughter appeared in public. The latter is called Irina: she is a doctor and the mother of their only grandchild called Oksana. Raisa Gorbachev was not only charming, poised, graceful and sophisticated but also extremely well read, with a mind of her own. She believed in expressing her opinion loud and clear, much to the resentment of many Soviet citizens.

By 1955, Nikita Khrushchev had taken over and the terror and fear of the Stalin regime was fast fading. Gorbachev had been very critical of Stalin’s oppressive and brutal methods, even during the time of Stalin’s rule in the USSR. This was before Stalin and his rule of terror were denounced by Khrushchev at the 20th Communist Party congress in 1956. Nothing definite can be said about Gorbachev’s political orientation at this stage, as glasnost unfortunately does not extend to the personal life of its author. Michael Tatu, a well-known French writer on Soviet affairs and the author of a biography on Gorbachev, has claimed that Gorbachev took an active part and played a leading role in the last purge launched by Joseph Stalin shortly before his death in 1953. This purge has been described by some as an anti-Semitic one.

The next 23 years of Gorbachev’s life were spent in the Stavropol area. He had already joined the Young Communist League or the Komsomol even before leaving his native village. He now put his heart and soul in his work for the Komsomol and from 1956 to 1958 worked as first secretary Stavropol city Komsomol organization. For the next four years he continued to work for the Komsomol: first as propaganda chief, then second secretary and finally as chief secretary. In 1963 Gorbachev was made chief of the agricultural department for the entire region of Stavropol, remarkable achievement for one so young as Gorbachev was only 32 years of age.

Gorbachev’s career took a sudden upward turn when he was appointed First Secretary of the Communist Party committee for the city of Stavropol in September 1966, later to become second secretary of the Stavropol territory party committee in August 1969. At the age of 39 he became First Secretary in April 1970, standing out as the youngest among the provincial chiefs in the whole of the USSR. One redeeming feature of his rule was that unlike other Russian rulers he remained open and accessible to anyone with a genuine complaint or grievance. As a matter of habit or policy, he always walked to his office on Lenin Square and any citizen was free to approach him instead of making an appointment to see him in his office. Boredom and monotony of rural life was broken when the Gorbachevs took foreign trips as members of state delegations. Their first trip to Western Europe was in 1966 when they rented a small car and travelled extensively through France and Italy.

At the age of 49, he was the youngest member of the Politburo: 8 years younger than the next youngest member and 21 years younger than the average age of Politburo members

Gorbachev’s hard work and dedication was finally noticed, appreciated and rewarded by the party high command in Moscow when he was elevated to the post of Deputy to the formal legislative body of the USSR in 1970 and given charge of the conservation and youth affairs commission, of which he became chairman in 1970 and along the way he was also named as the member of the all-powerful central committee in 1971. In the mysterious world of Kremlin politics talent, honesty and dedication were not the only criteria needed to climb the ladder of success: having powerful and influential mentors mattered more. Gorbachev was extremely lucky to be counted as the protégé of Mikhail Suslov, a former provincial party chief very close to Leonid Brezhnev – a man who was also the ideology minister in the Breznev cabinet. Suslov’s pressure group in the Kremlin included KGB chairman Yuri Andropov and the agricultural secretary Fyodor Kulakov. These three put together were the most powerful, formidable and influential trio in the high command of the Supreme Soviet.

Fyodor Kulakov died suddenly in 1978 and the post of communist party central secretary for agriculture fell vacant. To fill the post, Brezhnev chose Gorbachev obviously on the backing and strong recommendations of both Suslov and Andropov. Leonid Brezhnev had met Gorbachev only once briefly and this meeting had taken place at a small and remote railway station on 19 September 1978.

At the relatively young age of 47, Gorbachev became a member of the top national hierarchy and was given charge of the most troublesome area of the Soviet economy. This was a most difficult and daunting task, as agriculture had been widely recognised as the Achilles Heel of the entire Soviet System. Brezhnev’s health was fast failing and his 18-year-long regime was a cesspool of corruption and stagnation. Gorbachev in spite of all good intentions and hard work suffered one misfortune after another. There were a series of crop failures attributable to climate and a corrupt and inefficient bureaucratic system. Grain production came down from 230 million tons in 1978 to 155 million tons in 1981 and the situation reached a point when the government had to stop the publication of agricultural statistics. Billions of dollars were spent to purchase food grains from abroad.

Surprisingly, Gorbachav’s career did not suffer as a result of this fiasco. His rise continued and he was appointed a nonvoting member of the Politburo in November 1979, becoming a full member in October 1980. At the age of 49, he was the youngest member of the Politburo: 8 years younger than the next youngest member and 21 years younger than the average age of Politburo members.

Aging and almost totally senile Brezhnev died in 1982 and Gorbachev’s mentor Yuri Andropov became the Secretary General. Immediately after taking charge the simple, honest and austere Andropov started a series of revolutionary and far-reaching reforms in all spheres of Soviet society, including the purge of corrupt and incompetent party officials. Andropov’s failing health now forced him to rely more and more on his protégé Gorbachev who now became the mainstay and also liaised with the party hierarchy and foreign leaders. In 1984 Gorbachev was also named the chairman of the powerful foreign relations committee. He publicly called the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan a “grave mistake” and the war “a bleeding wound” but he always defended the Soviet Afghan policy.

Andropov’s life was cut short by kidney failure in early 1984. Kremlin watchers had already guessed Gorbachev as successor of his mentor, but this was not to be as the old guard of the Kremlin rallied to elect 72-year-old Chernenko as the new secretary general. Gorbachev went along awaiting his turn possibly even when making the nomination speech. Chernenko was so sick and infirm that during his short one-year reign that it was Gorbachev who managed all the affairs of state.

Immediately after the death of Chernenko, a fierce but brief power struggle ensued. Gorbechev’s main rival was Gregory Romanov, but he had to bow before the inevitable. In the emergency meeting of the Central Committee on 11 March 1985 just a few hours after Chernenko’s death, Gorbachev was elected Secretary General and the supreme ruler of the USSR – ironically to preside over the disintegration of his country.