Women yearned for his magic touch. Male stylists finally began to find a mentor who generously shared his knowledge and hairdressing finally found respectability and was no longer viewed as a lowly profession. But tragedy struck. Tariq’s mother was diagnosed with cancer. Packing up, wife Fayeza (who was a model) and his son Durran (his daughter Diya was born later) in tow, he returned home to Islamabad in 1993.

Much like how Mother Nature can overpower the most invincible of obstacles, Tariq’s impact was not hindered by his geographical location. If anything, the man went from strength to strength, rooting himself as a giant in hair and make- up, styling and the industry as a whole.

In 1997, he was the only Pakistani make-up artist at Paris Fashion Week. ‘I was doing Nilofer Shahid’s show in Paris, alongside Givenchy and Dior. There were thirty models in Givenchy, and thirty make-up artists doing their styling. An equal number of models for Dior and individual make-up artists there too. And of course, thirty models for Nilofer’s show and one Tariq Amin. They had lip gloss and we had teekas and jhoomars!’ When it came to work, Tariq Amin was a self-confessed beast.

In 2002, Pakistan hosted a show at the Royal Albert Hall in London. It was the very first of its kind and Tariq Amin was the sole hair and make-up artist. ‘It was called the Rhythms of the Indus and it was a big milestone.’ This was the international entry that the industry needed. Attended by London’s finest media, society and diaspora, this show cemented the who’s who and the cream of the fashion industry.

Throughout this, for Tariq personally, there had always been the intention of setting up a profession that would create an industry. ‘We all wanted things to happen, but I always wanted to be part of an industry. I brought a revolution, as I made this business respectable. People said, ‘We want to be like Tariq’.’

While designers were sprouting through all of 1980s and early 1990s, models were still hard to come by. Modelling was dominated by Lollywood starlets like Babra Sharif, Reema, Resham, and Meera, all of whom had a fan following for their films, but were not as inspirational as models.

Enter Tariq, who handpicked models and turned them into supermodels, paving the way for a market for modelling. ‘Models need to be role models for everybody else. I found girls like Aliya Zaidi, Atiya Khan, Sonya Mehnaz, Sara Akhtar. These are people who are our ‘girls’, our Christys and Cindys. When they walked out, they exuded class. People would say, ‘I want Sara Akhtar’s hair, I want Aliya Zaidi’s hair.’ Nobody ever came and said, ‘I want Meera’s hair or Reema’s hair’.’

Tariq’s ability to pick a model is what made the original girls stand out, and to date, the original models are remembered for their unmatched beauty and class. ‘The models back then were natural, and they still are. None of them have had anything done. Atiya is still beautiful. Bibi is gorgeous.’

Having created a market for models, he also channelled his energy into setting unmatched standards of professionalism and quality, which won him awards. He went on to win the first Sunsilk Hair Show and the first Lux award, both for hair and make- up. ‘I’ve always been my own competition. I have worked like a possessed man for thirty-five years. I had worked ten years in the eighties and the nineties—five years at Shaheen, five years at Daulat—and twenty-five years on my own.’

This resulted in him setting the standards of who he was willing to work with and many people were rejected in a vein not very different to Steve Rubell’s. It was never about saying yes to every opportunity, but more a case of establishing a bar, a standard of quality. Not so much to retain the ‘eliteness’ of the industry, but to ensure the work that was done was of an international standard and never compromised. ‘My God! I would say no all the time. Everybody would say, ‘Ho jayega’, I would say, ‘Nahin, nahin ho sakta hai.’.’

And that defines who he is. Not one to follow the herd, Tariq Amin was the sole figure—and still is—who advocated that utterly significant element for any industry to flourish: individuality. ‘In Pakistan, I was the first guy to have earrings, a ponytail and the first who publicly showed affection in a club.’ It was this wild attitude that enabled Tariq to create an image of his own, unperturbed by the waves of dismay, shock, or awe. ‘I love being an individual. I love being who I am, otherwise the amount of time I spend standing in front of a mirror…? I would hate myself.’

The sea of creativity flowing strong within, Tariq began doing makeovers for private clients; the most famous one being the makeover he gave to the actress of the time, Marina Khan. In the 1980s, Marina was the golden girl of the electronic media through her strong portrayals in her television plays. She inspired a generation of girls with her tomboyish hair and androgynous dressing. What did Tariq do to her? ‘I gave her a Linda Evangelista inspired blonde haircut.’ Instead of being shocked, the result was that the country fell even more in love with her.

Seeing Marina rock a blunt, blonde look kick-started the blonde hair that is almost part of the ‘Pakistani look’ now. ‘Being blonde in Pakistan means you’re spending money on yourself. The blonder you are, the richer you are.’ Rich or not, Tariq’s makeover had such an impact that girls of all socio-economic backgrounds rushed to salons to get blonde in their hair.

Similarly when Pakistan’s biggest film star, Shaan Shahid approached him for what is now an iconic music video, ‘Khamaaj’, it was Tariq’s styling that changed his image completely. Up until that point, Shaan was viewed via the lens of the characters he played which consisted of Punjabi, rural badmaash hero types. ‘Khamaaj’ redefined the man, washing away away all previous images or personas, ushering in a suave, sophisticated look that no other star achieved. Ali Zafar too was discovered by Tariq who then went on to give him his biggest hit, ‘Channo’.

What is also remarkable is that in a most gracious manner, Tariq also mentored and trained ninety per cent of the stylists he considers his competitors today. Nobody had ever done that and the idea of training others was unheard of. A lot of this had to do with the fact that Tariq came from a background that enabled him to see the larger picture. ‘I’m a well brought up old man. I’ve never been malicious. I wish them the best of luck. I am a simple man’ It wasn’t just about creating a career for himself. It was about setting a gold standard. Rukaiya, Mubasher, Humayun, Natasha, Nina Lotia, Sagar... the list is endless. I’ve been blamed for creating so many ‘monsters’! I brought the standard up. I was the only one doing work of an international standard. . . . It is very difficult. My aesthetics are very different to other people’s but that’s just because of who I am, what school I went to, who I partied with and obviously working with people like Tapu, Fifi and Arif, who are educated and aware.’

Although Tariq credits the original batch of designers for their work, he set a whole new awareness of what style consisted of in the sense that it had to go beyond a jora. ‘You could tell a Rizwan Beyg ensemble. You could tell what Nilofer had made. [But] I think if your hair looks great and you wear an attey ki bori, you’ll look like a million dollars. You can wear Gucci and Pucci and have a two hundred bucks blow dry and look like nothing on earth. Grooming makes a difference.’

If one looks at the giants, they all had two major things in common—quality education and exposure—which led to a deeper awareness that at times remains unmatched. Perhaps this is why the dream team of Tariq and Tapu produced some of Pakistan’s best photo shoots. ‘We were not doing something sordid. Tapu is a great guy, a wonderful photographer, wonderful to work with. Creative, amazing aesthetic. It is very difficult to find people that click with you creatively.’

In Tapu, not only did Tariq find a kindred spirit creatively, but also someone who understood the need to maintain quality and originality. Consequently they never opened a Vogue and copied what they saw. If anything, their work meant sheer dedication and a catalyst for the industry.

Tariq’s exit from Karachi in 1993 left a void which to date has not been filled by anyone. Although many hair and make-up stylists emerged in his wake none of them ever attained the status that Tariq has and it is unlikely the country will ever see another one of him.

Like his haunt, Studio 54, that is steeped in legacy and fame and seen as a hallmark of what glamour and progress ought to be, Tariq too is a legend of his own making, unmatched and certainly unforgettable.

Much like how Mother Nature can overpower the most invincible of obstacles, Tariq’s impact was not hindered by his geographical location. If anything, the man went from strength to strength, rooting himself as a giant in hair and make- up, styling and the industry as a whole.

In 1997, he was the only Pakistani make-up artist at Paris Fashion Week. ‘I was doing Nilofer Shahid’s show in Paris, alongside Givenchy and Dior. There were thirty models in Givenchy, and thirty make-up artists doing their styling. An equal number of models for Dior and individual make-up artists there too. And of course, thirty models for Nilofer’s show and one Tariq Amin. They had lip gloss and we had teekas and jhoomars!’ When it came to work, Tariq Amin was a self-confessed beast.

In 2002, Pakistan hosted a show at the Royal Albert Hall in London. It was the very first of its kind and Tariq Amin was the sole hair and make-up artist. ‘It was called the Rhythms of the Indus and it was a big milestone.’ This was the international entry that the industry needed. Attended by London’s finest media, society and diaspora, this show cemented the who’s who and the cream of the fashion industry.

Throughout this, for Tariq personally, there had always been the intention of setting up a profession that would create an industry. ‘We all wanted things to happen, but I always wanted to be part of an industry. I brought a revolution, as I made this business respectable. People said, ‘We want to be like Tariq’.’

While designers were sprouting through all of 1980s and early 1990s, models were still hard to come by. Modelling was dominated by Lollywood starlets like Babra Sharif, Reema, Resham, and Meera, all of whom had a fan following for their films, but were not as inspirational as models.

Enter Tariq, who handpicked models and turned them into supermodels, paving the way for a market for modelling. ‘Models need to be role models for everybody else. I found girls like Aliya Zaidi, Atiya Khan, Sonya Mehnaz, Sara Akhtar. These are people who are our ‘girls’, our Christys and Cindys. When they walked out, they exuded class. People would say, ‘I want Sara Akhtar’s hair, I want Aliya Zaidi’s hair.’ Nobody ever came and said, ‘I want Meera’s hair or Reema’s hair’.’

Tariq’s ability to pick a model is what made the original girls stand out, and to date, the original models are remembered for their unmatched beauty and class. ‘The models back then were natural, and they still are. None of them have had anything done. Atiya is still beautiful. Bibi is gorgeous.’

Having created a market for models, he also channelled his energy into setting unmatched standards of professionalism and quality, which won him awards. He went on to win the first Sunsilk Hair Show and the first Lux award, both for hair and make- up. ‘I’ve always been my own competition. I have worked like a possessed man for thirty-five years. I had worked ten years in the eighties and the nineties—five years at Shaheen, five years at Daulat—and twenty-five years on my own.’

Tariq’s exit from Karachi in 1993 left a void which to date has not been filled by anyone

This resulted in him setting the standards of who he was willing to work with and many people were rejected in a vein not very different to Steve Rubell’s. It was never about saying yes to every opportunity, but more a case of establishing a bar, a standard of quality. Not so much to retain the ‘eliteness’ of the industry, but to ensure the work that was done was of an international standard and never compromised. ‘My God! I would say no all the time. Everybody would say, ‘Ho jayega’, I would say, ‘Nahin, nahin ho sakta hai.’.’

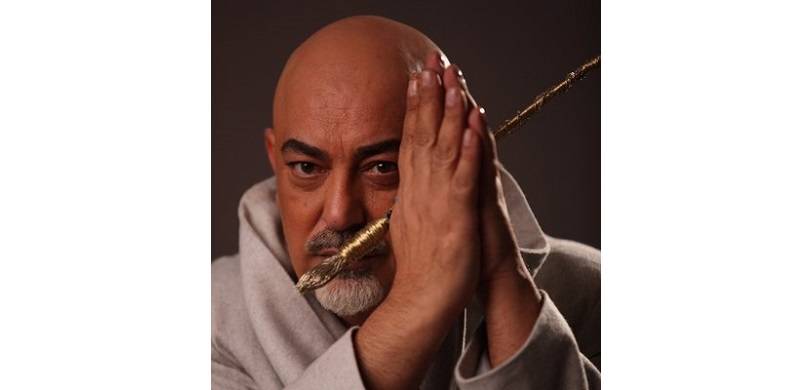

And that defines who he is. Not one to follow the herd, Tariq Amin was the sole figure—and still is—who advocated that utterly significant element for any industry to flourish: individuality. ‘In Pakistan, I was the first guy to have earrings, a ponytail and the first who publicly showed affection in a club.’ It was this wild attitude that enabled Tariq to create an image of his own, unperturbed by the waves of dismay, shock, or awe. ‘I love being an individual. I love being who I am, otherwise the amount of time I spend standing in front of a mirror…? I would hate myself.’

The sea of creativity flowing strong within, Tariq began doing makeovers for private clients; the most famous one being the makeover he gave to the actress of the time, Marina Khan. In the 1980s, Marina was the golden girl of the electronic media through her strong portrayals in her television plays. She inspired a generation of girls with her tomboyish hair and androgynous dressing. What did Tariq do to her? ‘I gave her a Linda Evangelista inspired blonde haircut.’ Instead of being shocked, the result was that the country fell even more in love with her.

Seeing Marina rock a blunt, blonde look kick-started the blonde hair that is almost part of the ‘Pakistani look’ now. ‘Being blonde in Pakistan means you’re spending money on yourself. The blonder you are, the richer you are.’ Rich or not, Tariq’s makeover had such an impact that girls of all socio-economic backgrounds rushed to salons to get blonde in their hair.

Similarly when Pakistan’s biggest film star, Shaan Shahid approached him for what is now an iconic music video, ‘Khamaaj’, it was Tariq’s styling that changed his image completely. Up until that point, Shaan was viewed via the lens of the characters he played which consisted of Punjabi, rural badmaash hero types. ‘Khamaaj’ redefined the man, washing away away all previous images or personas, ushering in a suave, sophisticated look that no other star achieved. Ali Zafar too was discovered by Tariq who then went on to give him his biggest hit, ‘Channo’.

What is also remarkable is that in a most gracious manner, Tariq also mentored and trained ninety per cent of the stylists he considers his competitors today. Nobody had ever done that and the idea of training others was unheard of. A lot of this had to do with the fact that Tariq came from a background that enabled him to see the larger picture. ‘I’m a well brought up old man. I’ve never been malicious. I wish them the best of luck. I am a simple man’ It wasn’t just about creating a career for himself. It was about setting a gold standard. Rukaiya, Mubasher, Humayun, Natasha, Nina Lotia, Sagar... the list is endless. I’ve been blamed for creating so many ‘monsters’! I brought the standard up. I was the only one doing work of an international standard. . . . It is very difficult. My aesthetics are very different to other people’s but that’s just because of who I am, what school I went to, who I partied with and obviously working with people like Tapu, Fifi and Arif, who are educated and aware.’

Although Tariq credits the original batch of designers for their work, he set a whole new awareness of what style consisted of in the sense that it had to go beyond a jora. ‘You could tell a Rizwan Beyg ensemble. You could tell what Nilofer had made. [But] I think if your hair looks great and you wear an attey ki bori, you’ll look like a million dollars. You can wear Gucci and Pucci and have a two hundred bucks blow dry and look like nothing on earth. Grooming makes a difference.’

If one looks at the giants, they all had two major things in common—quality education and exposure—which led to a deeper awareness that at times remains unmatched. Perhaps this is why the dream team of Tariq and Tapu produced some of Pakistan’s best photo shoots. ‘We were not doing something sordid. Tapu is a great guy, a wonderful photographer, wonderful to work with. Creative, amazing aesthetic. It is very difficult to find people that click with you creatively.’

In Tapu, not only did Tariq find a kindred spirit creatively, but also someone who understood the need to maintain quality and originality. Consequently they never opened a Vogue and copied what they saw. If anything, their work meant sheer dedication and a catalyst for the industry.

Tariq’s exit from Karachi in 1993 left a void which to date has not been filled by anyone. Although many hair and make-up stylists emerged in his wake none of them ever attained the status that Tariq has and it is unlikely the country will ever see another one of him.

Like his haunt, Studio 54, that is steeped in legacy and fame and seen as a hallmark of what glamour and progress ought to be, Tariq too is a legend of his own making, unmatched and certainly unforgettable.