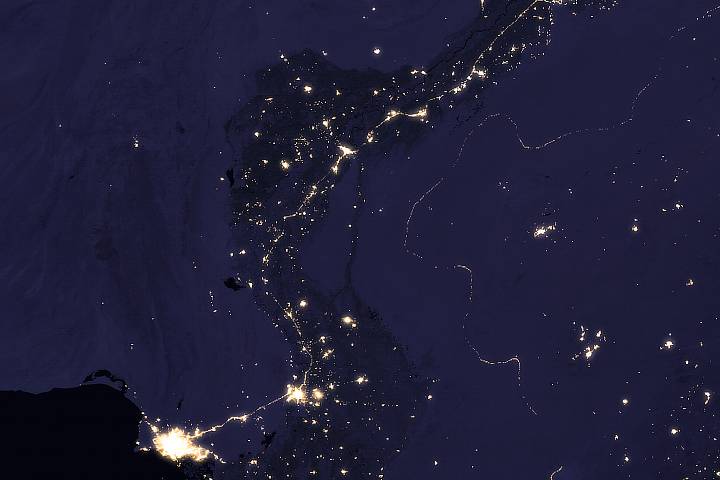

India and Pakistan have had a contentious relationship since 1947. Some romanticise the relationship calling it sibling rivalry, others claim that while there are two different countries, the people are one and the same. For decades, in spite of political differences, cultural relations remained cordial with the arts, music, fashion and literary exchanges reminding us that politics is but one mere element that can be overcome. Then on February 14th 2020 while the world celebrated love, the Pulwama incident ended any hope for civility – the love was long lost – between the two.

The silence and eeriness of No Man’s Land spilled over. Politics won.

Sabin Muzaffar works in Dubai. She is the founder of the digital media platform Ananke which regularly hosts professionals from all over the globe. She has worked tirelessly for gender equality, innovation, sustainability and education. Recognised by the UN and the Cherie Blair Foundation, she ventured into the literary industry post Indo-Pak breakdown which saw both Pakistani authors and Indian publishers in a state of despair and hopelessness. Realising she was in a land which could be seen as neutral territory, she set up the world’s first Women In Literature Festival (WLF).

Sabin Muzaffar works in Dubai. She is the founder of the digital media platform Ananke which regularly hosts professionals from all over the globe. She has worked tirelessly for gender equality, innovation, sustainability and education. Recognised by the UN and the Cherie Blair Foundation, she ventured into the literary industry post Indo-Pak breakdown which saw both Pakistani authors and Indian publishers in a state of despair and hopelessness. Realising she was in a land which could be seen as neutral territory, she set up the world’s first Women In Literature Festival (WLF).“When we established Anankemag.com, the idea and goal was to create inclusive conversations in the digital realm. All forms of art, be it the written word, theatre have the power to move mountains, instill empathy. The idea of WLP was always an attempt to offer access to everyone – a young woman in a remote village in India, Pakistan or anywhere else in the world who has access to the internet through her phone does not need money, a visa and all the trivialities that challenge her,” says Sabin.

Bringing authors, publishers, writers, academics and more from all over the world, WLF offered a dazzling array of conversations in 2021 and in 2022. Where physical engagement ended at No Man’s Land, digital communication began to take place in another dusty patch of land via Ananke. One of the conversations featuring two writers – Naveen Kishore and Hammad Rind - filled with the beauty of language and the love for the Other may have ended on the screen but the spill over had begun.

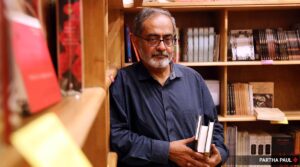

Naveen Kishore, a theatre practitioner set up Seagull Books in 1982. An award-winning publishing house based in Calcutta, Seagull Books has focused on translating and publishing world literature in English, culture, non-fiction, art, cinema and more. Earlier this year in February, Naveen’s first book of poems was published. A stunning collection, Knotted Grief explored the emotion of Grief and the rawness of the human experience particularly in the context of the war-torn country of Kashmir.

Naveen Kishore, a theatre practitioner set up Seagull Books in 1982. An award-winning publishing house based in Calcutta, Seagull Books has focused on translating and publishing world literature in English, culture, non-fiction, art, cinema and more. Earlier this year in February, Naveen’s first book of poems was published. A stunning collection, Knotted Grief explored the emotion of Grief and the rawness of the human experience particularly in the context of the war-torn country of Kashmir.

When asked what caused him to write such lines, Naveen doesn’t hold back. “Six decades of unknowingly leaving a paradise and returning to the nightmare it had metamorphosed into. Kashmir. And of course the affections of growing comfortable with grieving—both in the way you and I do these days when we speak of land nation woman man. The human condition. And the intimate one. The one we sometimes call loss. I think what I am attempting to suggest is that this is our life. Our lives. And therefore the grief is not entirely without hope. My poems are filled with hope. And not as a didactic message. It just is. An intuitive arriving at hope through this ‘condemning’ you speak of,” says Naveen.

Award nominated author Hammad Rind lives in Wales. He wrote ‘Four Dervishes’ in 2022. In his book, there are four strangers who come together one night and tell stories. They are seeking shelter from the rain. Weaving in cultures and languages, Hammad’s book transcends all man-made barriers to get to the core of the human experience as well. Most fascinating is how his work has a universal appeal despite the literary mosaic of words from different languages he puts together.

“Languages have been an obsession for me since a very early age. I grew up speaking Urdu and hearing Punjabi and Saraiki around me. Then there were English and Arabic at school. But I found this linguistic diversity insufficient. It was this unquenchable thirst for finding out, knowing and learning more that has been behind this lifelong passion,” says Hammad.

Perhaps it was the love of stories, the appreciation of languages or just the recognition of the Other as a fellow ‘writer’ free from the constraints of geography and limitations of identities, but over the summer Naveen and Hammad embarked on a shared journey where Hammad began to translate Naveen’s work into Urdu.

“I started translating between some of my languages – predominantly from and into Urdu, English and Persian – a few years ago. At this stage, I was mainly interested in translating classical poetry and folk wisdom from 'Eastern' languages and translating parts of 'essential' texts written in 'Western' languages such as works by Edward Said or Hannah Arendt for Urdu-reading audiences. Knotted Grief is my first book-length project and I loved and enjoyed it from the outset – it is contemporary yet the themes it deals with, such as grief, joy, freedom, have always concerned us humans - are essential to us. I also found translating from and into azad nazm or free verse, i.e. free from the constraints and rigidity of metre and rhyme, liberating,” says Hammad.

The most remarkable aspect has been the decolonisation aspect. Formed by human suffering particularly in Kashmir, written in English and now being translated into Urdu it’s been a journey of friendship and recognition. At this point, it is wishful thinking that literature has defeated politics but the flicker of hope that No Man’s Land might once see friendly cross border exchange has certainly been lit.