Rarely are men who are renowned in their time gifted with both intellect and a caring heart. Noam Chomsky is the exception. The New York Times has long declared him the greatest living intellectual in the world today, and yet I found in him a down-to-earth, warm, sentient and compassionate human being.

Chomsky has sounded like a minor biblical prophet most of his life—attacking the rich and powerful and defending the weak and vulnerable. Since moving from MIT in Boston to the University in Arizona, a state with its desert conditions, he has cultivated a long and straggly beard; give him a staff and he will look the part.

Attaining the heights of his discipline, Chomsky is considered the founder of modern linguistics and has written over a hundred books. But he is more widely known as a paladin championing the weak and the vulnerable than a leading scientist. His latest book is titled Requiem for the American Dream: The 10 Principles of Concentration of Wealth & Power. Let me remind those who do not know the significance of the word “requiem” that it is part of the funeral rites for the soul of the dead.

In this article we will examine issues of race in America which engender different forms of violence and terrorism. While race is on the surface of society, understanding how it related to society’s deeper structures can help make sense of it. It is the failure to tackle race issues that is partly responsible for the turbulence in contemporary American society.

Chomsky had posited that all sentences have two structures: a phonetic or surface structure, and a semantic or deep structure. The surface structure determines how a sentence sounds; the deep structure determines the nuance in how a sentence is understood. This terminology has been borrowed by anthropologists such as Clifford Geertz and Claude Lévi-Strauss and applied to their anthropological studies. “One can become conscious of one’s grammatical categories by reading linguistic treatises just as one can become conscious of one’s cultural categories by reading ethnological ones,” argues Geertz in The Interpretation of Cultures. Deep structures, he maintains, can only be observed by analyzing the aggregate of a society’s surface structures, or the society’s ideas, habits, patterns, and institutions, and by “reconstructing the conceptual systems that, from deep beneath” the surface of society, animate and give it form. Ultimately, Geertz explains, “The job of the ethnologist is to describe the surface patterns as best he can, to reconstitute the deeper structures out of which they are built, and to classify those structures, once reconstituted, into an analytical scheme.”

I first met Chomsky as I set out to travel the United States in 2008 on my sabbatical year for the project that I called “Journey into America,” focusing on America’s relationship with Islam. I was accompanied by my team of young American scholars and students. The project resulted in an academic book called Journey into America, published in 2010, which won the American Book Award, and I also produced a documentary with the same title.

We had a very packed program and traveled to 75 towns and cities and visited a hundred mosques. We gathered rich ethnography and film footage. We interviewed Chomsky in Boston late in 2008 in his office. The meeting was arranged through the courtesy of my good friend Barry Hoffman who was—and is—Pakistan's honorary Consul General for decades.

Chomsky gave a detailed interview on camera for the documentary and book project. I reproduce extracts below. My team of young American scholars were in awe of Chomsky, so highly is he regarded. His work is also a tribute to the practice of democracy and freedom in the US. I cannot imagine a Chomsky surviving freely in any other country.

As one of the important themes in our study was about identity, and the different forms of American identity, my interest in Chomsky’s ideas circled around questions of identity. His brilliance and startling frankness fascinated us, especially the young team. Remember the cultural context of the interview. It was a time of widespread Islamophobia and the media was freely abusing and attacking Muslims as potential terrorists and generally a worthless community. There was suspicion and hostility. Mosques were attacked and women wearing the hijab sometimes assaulted. Most Americans preferred to sit on the fence and look away. None of this diverted or dulled Chomsky and his loyalty to his causes shone brighter.

When I asked Chomsky how he defined American identity, he replied, “That’s a very striking question in fact, because of course this is a country of immigrants, and the immigrants originally were mostly English, but then Germans, Scots, Irish, Swedish, Eastern Europeans like my parents, it is a melting pot. The problem of creating an identity was a crucial issue from the very beginning of the settlement. A lot of mythology was created as is typical for nations. Nations are myths, so they have founding myths, identity myths, and so on. And if you look back at the original colonists, the ones who came here, say to this area, they were religious fanatics, who were waving the holy book calling themselves the children of Israel returning to the holy land slaughtering the Amalekites following the Lord’s wishes, the Amalekites being the native population. The others poured in, many were similar, especially the Scots and Irish. They did develop a myth: it was an incredible myth in the 19th century, of Anglo-Saxon origins. We’re the true Anglo-Saxons, no matter where we came from. Going back to before the conquest, if you look over American history, each wave of immigrants at first was very harshly repressed. So in the Boston area where we are, there was a big Irish immigration after the Irish famine and so on. But the Irish were barely a cut above Blacks. There were signs, “No dogs or Irish allowed.” They gradually over time worked themselves in to the political system and the social system, and became a part of it.”

Commenting on anti-Semitism, we heard that Jewish students had to run home after school to escape racist bullies. “One of the reasons MIT is a great university is because Jews couldn’t get jobs at Harvard. So, they came down to the engineering school down the street, which didn’t have the same class bias. This is not all deep in the past, you know. And it has been true of, as I say, the Irish a century ago. I mean they were doing a lot, especially in gynecology and fields like that, which were developed a lot in Boston. I mean one of the reasons it advanced was because they were using Black and Irish women as subjects, doing horrifying experiments. It was considered normal.”

He then commented on his own ethnic community. “The Jewish immigration was pretty similar. Jews like my father worked in a sweatshop, Jews were the criminals, Murder Incorporated was run by the Jews, and finally they worked themselves and became schoolteachers, and became the most privileged minority in the country. And it has happened with wave after wave of immigrants. Earlier waves of immigration were absorbed into a growing manufacturing economy, but that wasn’t possible any longer with the Black internal immigration. So, what you see is a sharp rise in imprisonment from 1980 to the present. Incarceration has just shot out of any relationship to other countries or any relationship to crime.”

Chomsky then raised a fascinating point that is overlooked by most sociologists.

“Another dilemma that runs through the creation of American identity in this complex system is fear. It’s a very frightened country. Unusually so, by international standards, which is kind of ironic because at a level of security that nobody’s ever dreamed of in world history, but from the very beginning there’s a strong element of fear. You find it in popular literature, literature for the masses. Now it’s on television or movies or something, but for a long time it was in magazines and novels. The theme that runs through them from the eighteenth century, the theme is we’re about to be destroyed by an enemy, and at the last minute, a super weapon is discovered, or a hero arises, Rambo or something and somehow saves us. The Terminator or high school boys hiding in the mountains defending us from the Russians. This goes right back to the eighteenth century.

A secondary theme underlying it, is that the great enemy that’s about to destroy us is somebody we’re crushing. So, in the early years, the great enemy was the Indians. We are exterminating them, but they are about to exterminate us. Then it was the Blacks, the Black slaves. There’s going to be a slave uprising, all they want to do is rape white women and so on and so forth. And then, later on in the century, it was the Chinese. You think they are coming in here to start laundries, but in fact they’re planning to take over the country and destroy us. The progressive writers like Jack London were writing novels about how we have to kill everyone in China with bacteriological warfare to stop this nefarious plot before it goes too far. Then the Hispanics, and now its Muslims.”

I asked him about primordial Anglo-Saxon identity which dominated early American society.

“Anglo Saxon identity was really believed and it’s pure myth. Actually, you know, most nations are myths. I mean if you actually pay any attention to origins, the descendants of the original Jews are the Palestinians. It is a mythical system. But that’s what nations are, they’re mythical communities based on invented histories, founders who did not exist, you know, goals that do not exist, that somehow bind people together.”

I told Chomsky that many white Christian Americans that we interviewed defined American identity as meaning “freedom,” “liberty” and “democracy.”

“If you were in the Soviet Union, in the days when it existed, if you asked what Russian identity is, they would say, it is ‘workers rule the world, democracy, justice for everyone.’ You have things hammered in your head, you repeat them, but nobody believes them.

If you listen to [the radio talk show host] Rush Limbaugh, it has very much the ring of early Nazi propaganda, which I’m just about old enough to remember. He’s appealing to something real, fear and anger. People have had a rotten time.

For the last thirty years, for the majority of the population wages have stagnated, working hours have gone up, benefits have declined, and they’re angry and they’re frightened. And Limbaugh is organizing that fear. He speaks for ‘Us.’ Listen to him, it’s always, ‘We.’ That’s like Hitler blaming the plight of Germany on the Jews. That has very much the ring of early Nazi propaganda. And it worked. Let us not forget that it worked. I mean in the 1920s, Germany was at the peak of Western civilisation. I mean the sciences, the arts, the literature, you know, democratic politics, opposition voices, 10 years later, it was the most horrifying country in human history.

When they interview people about Obama, they say things like ‘Well maybe I’ll vote for him because he’s not a real Black. He’s not a real African American. He’s not going to give everything to the Blacks like the Democrats want and take it all away from us. Then somebody else will say, ‘Well how can I trust him not to give everything to the Blacks or the Muslims or somebody?’”

Chomsky recounted a story from when the American administration, led by its senior officials like Kissinger, was actively promoting the entire nuclear program for the Shah of Iran. MIT was to be fully involved. A debate was arranged where the faculty were almost unanimously in support of the proposal while 80% of the students opposed it. After the speeches, one of the organising deans told Chomsky, who had spoken against giving nuclear technology to Iran, “I thought you were pro-Arab.” Chomsky, recalling this incident, pointed out that the man who was supporting the program did not know the difference between Arab and Iranian. For Chomsky this is reflective of American ignorance about the rest of the world, which feeds into prejudices: “That’s the level of understanding you’re dealing with,” in how Americans classify people, he said, such as “calling everyone from Eastern Europe Huns, calling everyone from southern Europe wops.”

When I requested Chomsky to provide a blurb for my study Journey into Europe, he was again generous:

“Akbar Ahmed’s profound and careful inquiries have greatly enriched our understanding of Islam in the modern world. His latest study, based on direct research with a group of young scholars, explores the complex interfaith reality of Europe, both in history and today, from an Eastern perspective, reversing the familiar paradigm. It is sure to be yet another influential contribution, one greatly needed in a world riven by conflicts and misunderstanding.”

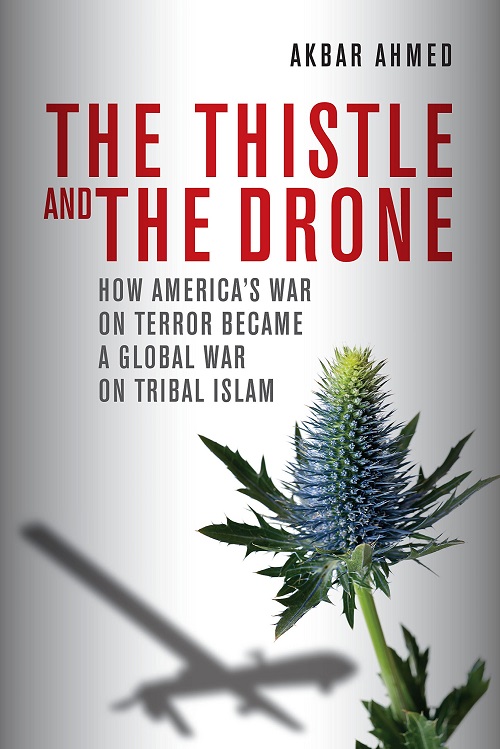

In an interview with the Gulf News in 2021, Chomsky quoted my work: “There are specialists on tribal societies, especially Afghanistan and Pakistan, people like Akbar Ahmed, a highly respected anthropologist who has been trying for 20 years to get somebody to listen to this. There is a wonderful book about it called The Thistle and the Drone.” The book documents the encounter between high tech weapons like the drone and its destructive impact on tribal societies across the world.

Earlier, he also referred to the same book in an interview with The Express Tribune in 2019 and on the Amy Goodman Show in 2015. On the latter he said: “There’s a very important book by Akbar Ahmed, who’s an important anthropologist, who is a Pakistani, who studies tribal systems and worked in the North-West territories and so on, and it’s called The Thistle and the Drone. And he goes through, in some detail, the effect on tribal societies of simply murdering—from their point of view, just murdering people at random.”

After the American debacle in Afghanistan, I sent him an article of mine.

“Wise and thoughtful words,” he replied. “If only they had listened to you. It would have been a much better world. Perhaps this time.”

Chomsky has sounded like a minor biblical prophet most of his life—attacking the rich and powerful and defending the weak and vulnerable. Since moving from MIT in Boston to the University in Arizona, a state with its desert conditions, he has cultivated a long and straggly beard; give him a staff and he will look the part.

Attaining the heights of his discipline, Chomsky is considered the founder of modern linguistics and has written over a hundred books. But he is more widely known as a paladin championing the weak and the vulnerable than a leading scientist. His latest book is titled Requiem for the American Dream: The 10 Principles of Concentration of Wealth & Power. Let me remind those who do not know the significance of the word “requiem” that it is part of the funeral rites for the soul of the dead.

In this article we will examine issues of race in America which engender different forms of violence and terrorism. While race is on the surface of society, understanding how it related to society’s deeper structures can help make sense of it. It is the failure to tackle race issues that is partly responsible for the turbulence in contemporary American society.

Chomsky had posited that all sentences have two structures: a phonetic or surface structure, and a semantic or deep structure. The surface structure determines how a sentence sounds; the deep structure determines the nuance in how a sentence is understood. This terminology has been borrowed by anthropologists such as Clifford Geertz and Claude Lévi-Strauss and applied to their anthropological studies. “One can become conscious of one’s grammatical categories by reading linguistic treatises just as one can become conscious of one’s cultural categories by reading ethnological ones,” argues Geertz in The Interpretation of Cultures. Deep structures, he maintains, can only be observed by analyzing the aggregate of a society’s surface structures, or the society’s ideas, habits, patterns, and institutions, and by “reconstructing the conceptual systems that, from deep beneath” the surface of society, animate and give it form. Ultimately, Geertz explains, “The job of the ethnologist is to describe the surface patterns as best he can, to reconstitute the deeper structures out of which they are built, and to classify those structures, once reconstituted, into an analytical scheme.”

I first met Chomsky as I set out to travel the United States in 2008 on my sabbatical year for the project that I called “Journey into America,” focusing on America’s relationship with Islam. I was accompanied by my team of young American scholars and students. The project resulted in an academic book called Journey into America, published in 2010, which won the American Book Award, and I also produced a documentary with the same title.

We had a very packed program and traveled to 75 towns and cities and visited a hundred mosques. We gathered rich ethnography and film footage. We interviewed Chomsky in Boston late in 2008 in his office. The meeting was arranged through the courtesy of my good friend Barry Hoffman who was—and is—Pakistan's honorary Consul General for decades.

Chomsky gave a detailed interview on camera for the documentary and book project. I reproduce extracts below. My team of young American scholars were in awe of Chomsky, so highly is he regarded. His work is also a tribute to the practice of democracy and freedom in the US. I cannot imagine a Chomsky surviving freely in any other country.

As one of the important themes in our study was about identity, and the different forms of American identity, my interest in Chomsky’s ideas circled around questions of identity. His brilliance and startling frankness fascinated us, especially the young team. Remember the cultural context of the interview. It was a time of widespread Islamophobia and the media was freely abusing and attacking Muslims as potential terrorists and generally a worthless community. There was suspicion and hostility. Mosques were attacked and women wearing the hijab sometimes assaulted. Most Americans preferred to sit on the fence and look away. None of this diverted or dulled Chomsky and his loyalty to his causes shone brighter.

Chomsky then raised a fascinating point that is overlooked by most sociologists. “Another dilemma that runs through the creation of American identity in this complex system is fear. It’s a very frightened country. Unusually so, by international standards, which is kind of ironic because at a level of security that nobody’s ever dreamed of in world history, but from the very beginning there’s a strong element of fear. You find it in popular literature, literature for the masses. Now it’s on television or movies or something, but for a long time it was in magazines and novels

When I asked Chomsky how he defined American identity, he replied, “That’s a very striking question in fact, because of course this is a country of immigrants, and the immigrants originally were mostly English, but then Germans, Scots, Irish, Swedish, Eastern Europeans like my parents, it is a melting pot. The problem of creating an identity was a crucial issue from the very beginning of the settlement. A lot of mythology was created as is typical for nations. Nations are myths, so they have founding myths, identity myths, and so on. And if you look back at the original colonists, the ones who came here, say to this area, they were religious fanatics, who were waving the holy book calling themselves the children of Israel returning to the holy land slaughtering the Amalekites following the Lord’s wishes, the Amalekites being the native population. The others poured in, many were similar, especially the Scots and Irish. They did develop a myth: it was an incredible myth in the 19th century, of Anglo-Saxon origins. We’re the true Anglo-Saxons, no matter where we came from. Going back to before the conquest, if you look over American history, each wave of immigrants at first was very harshly repressed. So in the Boston area where we are, there was a big Irish immigration after the Irish famine and so on. But the Irish were barely a cut above Blacks. There were signs, “No dogs or Irish allowed.” They gradually over time worked themselves in to the political system and the social system, and became a part of it.”

Commenting on anti-Semitism, we heard that Jewish students had to run home after school to escape racist bullies. “One of the reasons MIT is a great university is because Jews couldn’t get jobs at Harvard. So, they came down to the engineering school down the street, which didn’t have the same class bias. This is not all deep in the past, you know. And it has been true of, as I say, the Irish a century ago. I mean they were doing a lot, especially in gynecology and fields like that, which were developed a lot in Boston. I mean one of the reasons it advanced was because they were using Black and Irish women as subjects, doing horrifying experiments. It was considered normal.”

He then commented on his own ethnic community. “The Jewish immigration was pretty similar. Jews like my father worked in a sweatshop, Jews were the criminals, Murder Incorporated was run by the Jews, and finally they worked themselves and became schoolteachers, and became the most privileged minority in the country. And it has happened with wave after wave of immigrants. Earlier waves of immigration were absorbed into a growing manufacturing economy, but that wasn’t possible any longer with the Black internal immigration. So, what you see is a sharp rise in imprisonment from 1980 to the present. Incarceration has just shot out of any relationship to other countries or any relationship to crime.”

Chomsky then raised a fascinating point that is overlooked by most sociologists.

“Another dilemma that runs through the creation of American identity in this complex system is fear. It’s a very frightened country. Unusually so, by international standards, which is kind of ironic because at a level of security that nobody’s ever dreamed of in world history, but from the very beginning there’s a strong element of fear. You find it in popular literature, literature for the masses. Now it’s on television or movies or something, but for a long time it was in magazines and novels. The theme that runs through them from the eighteenth century, the theme is we’re about to be destroyed by an enemy, and at the last minute, a super weapon is discovered, or a hero arises, Rambo or something and somehow saves us. The Terminator or high school boys hiding in the mountains defending us from the Russians. This goes right back to the eighteenth century.

A secondary theme underlying it, is that the great enemy that’s about to destroy us is somebody we’re crushing. So, in the early years, the great enemy was the Indians. We are exterminating them, but they are about to exterminate us. Then it was the Blacks, the Black slaves. There’s going to be a slave uprising, all they want to do is rape white women and so on and so forth. And then, later on in the century, it was the Chinese. You think they are coming in here to start laundries, but in fact they’re planning to take over the country and destroy us. The progressive writers like Jack London were writing novels about how we have to kill everyone in China with bacteriological warfare to stop this nefarious plot before it goes too far. Then the Hispanics, and now its Muslims.”

I asked him about primordial Anglo-Saxon identity which dominated early American society.

“Anglo Saxon identity was really believed and it’s pure myth. Actually, you know, most nations are myths. I mean if you actually pay any attention to origins, the descendants of the original Jews are the Palestinians. It is a mythical system. But that’s what nations are, they’re mythical communities based on invented histories, founders who did not exist, you know, goals that do not exist, that somehow bind people together.”

I told Chomsky that many white Christian Americans that we interviewed defined American identity as meaning “freedom,” “liberty” and “democracy.”

“If you were in the Soviet Union, in the days when it existed, if you asked what Russian identity is, they would say, it is ‘workers rule the world, democracy, justice for everyone.’ You have things hammered in your head, you repeat them, but nobody believes them.

If you listen to [the radio talk show host] Rush Limbaugh, it has very much the ring of early Nazi propaganda, which I’m just about old enough to remember. He’s appealing to something real, fear and anger. People have had a rotten time.

For the last thirty years, for the majority of the population wages have stagnated, working hours have gone up, benefits have declined, and they’re angry and they’re frightened. And Limbaugh is organizing that fear. He speaks for ‘Us.’ Listen to him, it’s always, ‘We.’ That’s like Hitler blaming the plight of Germany on the Jews. That has very much the ring of early Nazi propaganda. And it worked. Let us not forget that it worked. I mean in the 1920s, Germany was at the peak of Western civilisation. I mean the sciences, the arts, the literature, you know, democratic politics, opposition voices, 10 years later, it was the most horrifying country in human history.

When they interview people about Obama, they say things like ‘Well maybe I’ll vote for him because he’s not a real Black. He’s not a real African American. He’s not going to give everything to the Blacks like the Democrats want and take it all away from us. Then somebody else will say, ‘Well how can I trust him not to give everything to the Blacks or the Muslims or somebody?’”

Chomsky recounted a story from when the American administration, led by its senior officials like Kissinger, was actively promoting the entire nuclear program for the Shah of Iran. MIT was to be fully involved. A debate was arranged where the faculty were almost unanimously in support of the proposal while 80% of the students opposed it. After the speeches, one of the organising deans told Chomsky, who had spoken against giving nuclear technology to Iran, “I thought you were pro-Arab.” Chomsky, recalling this incident, pointed out that the man who was supporting the program did not know the difference between Arab and Iranian. For Chomsky this is reflective of American ignorance about the rest of the world, which feeds into prejudices: “That’s the level of understanding you’re dealing with,” in how Americans classify people, he said, such as “calling everyone from Eastern Europe Huns, calling everyone from southern Europe wops.”

When I requested Chomsky to provide a blurb for my study Journey into Europe, he was again generous:

“Akbar Ahmed’s profound and careful inquiries have greatly enriched our understanding of Islam in the modern world. His latest study, based on direct research with a group of young scholars, explores the complex interfaith reality of Europe, both in history and today, from an Eastern perspective, reversing the familiar paradigm. It is sure to be yet another influential contribution, one greatly needed in a world riven by conflicts and misunderstanding.”

In an interview with the Gulf News in 2021, Chomsky quoted my work: “There are specialists on tribal societies, especially Afghanistan and Pakistan, people like Akbar Ahmed, a highly respected anthropologist who has been trying for 20 years to get somebody to listen to this. There is a wonderful book about it called The Thistle and the Drone.” The book documents the encounter between high tech weapons like the drone and its destructive impact on tribal societies across the world.

Earlier, he also referred to the same book in an interview with The Express Tribune in 2019 and on the Amy Goodman Show in 2015. On the latter he said: “There’s a very important book by Akbar Ahmed, who’s an important anthropologist, who is a Pakistani, who studies tribal systems and worked in the North-West territories and so on, and it’s called The Thistle and the Drone. And he goes through, in some detail, the effect on tribal societies of simply murdering—from their point of view, just murdering people at random.”

After the American debacle in Afghanistan, I sent him an article of mine.

“Wise and thoughtful words,” he replied. “If only they had listened to you. It would have been a much better world. Perhaps this time.”