Migrants brings with them their own traditions and what we grow up with remains with us through our lives. Food is an integral part of that baggage, and is the tie with the comfort of a home. There is a ritualistic aspect to family meals which allows time for connection – among family members, across cities and continents and even across generations.

Women, particularly, have a nuanced relationship with meals. They are the traditionally the needle that weaves home life into a narrative of family histories and cultures. The kitchen is more than a hearth, it is literally the heart of a home. I consider the role it has played in my own life – my earliest childhood diaries were as much as daily meals and what we ate as school experiences.

Marrying into another family was an interesting experience for me. I realised each household was not just a separate unit – it was a recognisable microcosm with its own DNA. Embedded in them are memories dating back to childhood, which are radically different even if one grows up in the same neighbourhood or city.

My husband’s family originated from Baranbanki, a small town in UP India. As many Muslims did, they migrated to Dhaka, in what was then East Pakistan, and then eventually from Dhaka to Karachi in 1971. Relocation from India to what is now Bangladesh to what is now Pakistan, was more than physical migration. It created in them multiple layers of identities, nationalities and experiences. It is the story of many – how politics can uproot stable lives in a moment and then we carry with us what we know.

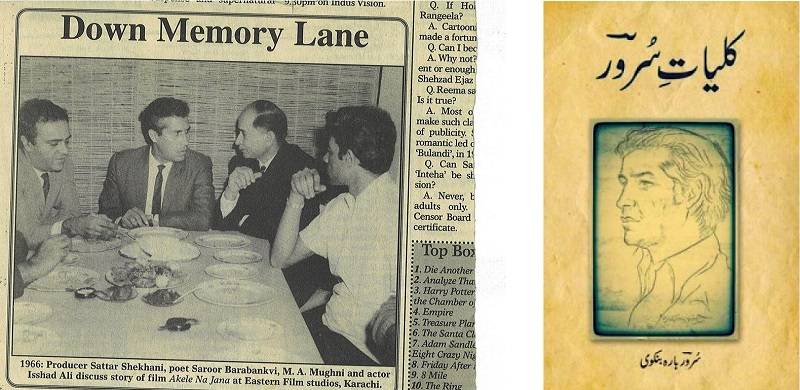

I never met my parents-in-law. They died before I met their son. My father-in-law, by all accounts, had an artistic temperament. He had a formidable reputation as an Urdu poet, writing under the pen name of Suroor Baranbanki. He was learned man, composed lyrics, made art movies (Aakhri Station) and lived in a milieu of creativity along with the likes of Sadiqain, Jamil Naqsh and Shabnam.

His wife was creative in her own way, looking after a growing family. The center of their home was the kitchen, where she spent much time – including to look after the array of like-minded creative people. They have both come to life through the stories and recipes passed down to us through their children. We learn of them through anecdotes of how quality ingredients would be used as a backdrop to the literary salon of their home over many evenings and through their migratory journey around the Subcontinent.

Movie-making and mushairas kept Suroor sahib away, so when he returned home, he would look forward to his wife’s meals. He would recount stories of how nawabs and rajas in India would cut off the hand of their cooks who made delicious food so they in turn could not cook it for others. As a form of tribute, he would wait for her to join them at the dinner table before eating.

Movie-making and mushairas kept Suroor sahib away, so when he returned home, he would look forward to his wife’s meals. He would recount stories of how nawabs and rajas in India would cut off the hand of their cooks who made delicious food so they in turn could not cook it for others. As a form of tribute, he would wait for her to join them at the dinner table before eating.

As a poet, he clearly had a way with words. At the appearance of a new moon, he would ask his wife to stand with him outside. He would close and open his eyes, see the moon and then shift his gaze to her face. His explanation was simple – look at the moon and then at a beautiful face. This was the poet in him and is the swoon-worthy stuff of dreams.

It also explains a lot about my husband’s romantic gestures over our marriage that often make his friends remark that he makes their lives that much harder, as their wives expect the same. To wear your heart on your sleeve is not easy and perhaps that is why we veer towards poets – that they can express in words feelings we are unable to express.

The keeper of the recipes, as is often the case, was their eldest daughter, who used to spend time in the kitchen helping her mother. Her father had named her Aiman, after Raga Aiman sung early in the morning. She memorised these family recipes and often cooks them for us when we visit.

Each meal together evokes memories of family we have never met or places we have never visited. As the next generation of cousins grow up in many parts of the world, each of the inheritors have used these and made them their way of life. It is a way to pass on the traditions they grew up with and are infused into their own lives.

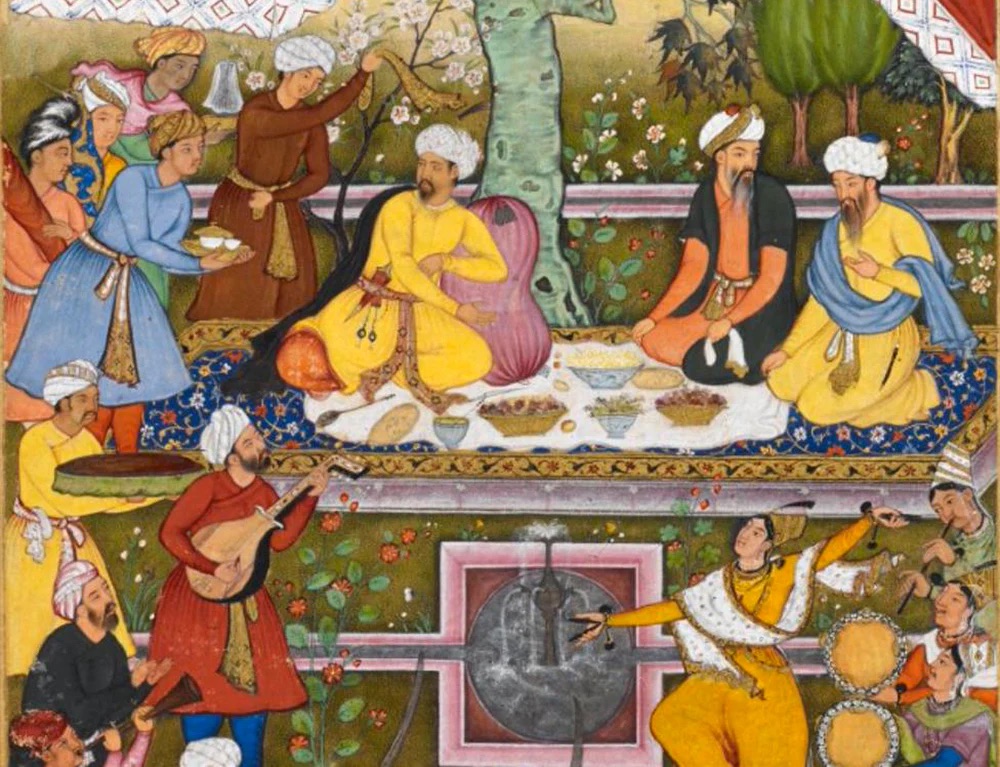

These recipes also have their own culinary heritage. Pasanday (tenderised beef) or galawat key kebab (pulverized meat) were developed as gourmet dishes in the era of Muslim dynasties in South Asia – the latter to feed a ruler who had sensitive teeth and found it difficult to chew.

Mughal cuisine itself was sophisticated by all accounts. The shahi khansama or cook would consult with the hakim (physician) about the medical benefits of the food for the royal menu. Even Ghalib the famous poet was remembered for his penchant for mangoes and was recorded to have said to Bahadur Shah Zafar that each morsel has the name of the person who will eat it.

My mother-in-law used some of these recipes, though simplified them with basic ingredients. When asked why her recipes were so simple but still tasted amazing – having tasted someone else’s heavily flavored halva – she retorted that “ghaas main bhi itna sub kuch daal do to who bhi mazaydar lagay gi” – that even if you add all these ingredients to grass, that too would taste good.

The Arabs have a word for this, “Nafas,” loosely translated into “breath” or “spirit” and similar to Urdu – that one has flavour in one’s hand. In the cooking context, that is an energy which makes some cooks exceptional. It is hard to identify but clearly has an emotional or psychological element. She used basic ingredients but with something intangible transformed it into something exceptional. Perhaps that was the poet’s muse in her.

I am grateful to inherit these recipes, for they are a powerful reminder of the beauty and strength it took to keep a family together, especially during traumas and transition.

Women, particularly, have a nuanced relationship with meals. They are the traditionally the needle that weaves home life into a narrative of family histories and cultures. The kitchen is more than a hearth, it is literally the heart of a home. I consider the role it has played in my own life – my earliest childhood diaries were as much as daily meals and what we ate as school experiences.

Marrying into another family was an interesting experience for me. I realised each household was not just a separate unit – it was a recognisable microcosm with its own DNA. Embedded in them are memories dating back to childhood, which are radically different even if one grows up in the same neighbourhood or city.

My husband’s family originated from Baranbanki, a small town in UP India. As many Muslims did, they migrated to Dhaka, in what was then East Pakistan, and then eventually from Dhaka to Karachi in 1971. Relocation from India to what is now Bangladesh to what is now Pakistan, was more than physical migration. It created in them multiple layers of identities, nationalities and experiences. It is the story of many – how politics can uproot stable lives in a moment and then we carry with us what we know.

I never met my parents-in-law. They died before I met their son. My father-in-law, by all accounts, had an artistic temperament. He had a formidable reputation as an Urdu poet, writing under the pen name of Suroor Baranbanki. He was learned man, composed lyrics, made art movies (Aakhri Station) and lived in a milieu of creativity along with the likes of Sadiqain, Jamil Naqsh and Shabnam.

His wife was creative in her own way, looking after a growing family. The center of their home was the kitchen, where she spent much time – including to look after the array of like-minded creative people. They have both come to life through the stories and recipes passed down to us through their children. We learn of them through anecdotes of how quality ingredients would be used as a backdrop to the literary salon of their home over many evenings and through their migratory journey around the Subcontinent.

Movie-making and mushairas kept Suroor sahib away, so when he returned home, he would look forward to his wife’s meals. He would recount stories of how nawabs and rajas in India would cut off the hand of their cooks who made delicious food so they in turn could not cook it for others. As a form of tribute, he would wait for her to join them at the dinner table before eating.

Movie-making and mushairas kept Suroor sahib away, so when he returned home, he would look forward to his wife’s meals. He would recount stories of how nawabs and rajas in India would cut off the hand of their cooks who made delicious food so they in turn could not cook it for others. As a form of tribute, he would wait for her to join them at the dinner table before eating.As a poet, he clearly had a way with words. At the appearance of a new moon, he would ask his wife to stand with him outside. He would close and open his eyes, see the moon and then shift his gaze to her face. His explanation was simple – look at the moon and then at a beautiful face. This was the poet in him and is the swoon-worthy stuff of dreams.

It also explains a lot about my husband’s romantic gestures over our marriage that often make his friends remark that he makes their lives that much harder, as their wives expect the same. To wear your heart on your sleeve is not easy and perhaps that is why we veer towards poets – that they can express in words feelings we are unable to express.

The keeper of the recipes, as is often the case, was their eldest daughter, who used to spend time in the kitchen helping her mother. Her father had named her Aiman, after Raga Aiman sung early in the morning. She memorised these family recipes and often cooks them for us when we visit.

Each meal together evokes memories of family we have never met or places we have never visited. As the next generation of cousins grow up in many parts of the world, each of the inheritors have used these and made them their way of life. It is a way to pass on the traditions they grew up with and are infused into their own lives.

These recipes also have their own culinary heritage. Pasanday (tenderised beef) or galawat key kebab (pulverized meat) were developed as gourmet dishes in the era of Muslim dynasties in South Asia – the latter to feed a ruler who had sensitive teeth and found it difficult to chew.

Mughal cuisine itself was sophisticated by all accounts. The shahi khansama or cook would consult with the hakim (physician) about the medical benefits of the food for the royal menu. Even Ghalib the famous poet was remembered for his penchant for mangoes and was recorded to have said to Bahadur Shah Zafar that each morsel has the name of the person who will eat it.

My mother-in-law used some of these recipes, though simplified them with basic ingredients. When asked why her recipes were so simple but still tasted amazing – having tasted someone else’s heavily flavored halva – she retorted that “ghaas main bhi itna sub kuch daal do to who bhi mazaydar lagay gi” – that even if you add all these ingredients to grass, that too would taste good.

The Arabs have a word for this, “Nafas,” loosely translated into “breath” or “spirit” and similar to Urdu – that one has flavour in one’s hand. In the cooking context, that is an energy which makes some cooks exceptional. It is hard to identify but clearly has an emotional or psychological element. She used basic ingredients but with something intangible transformed it into something exceptional. Perhaps that was the poet’s muse in her.

I am grateful to inherit these recipes, for they are a powerful reminder of the beauty and strength it took to keep a family together, especially during traumas and transition.