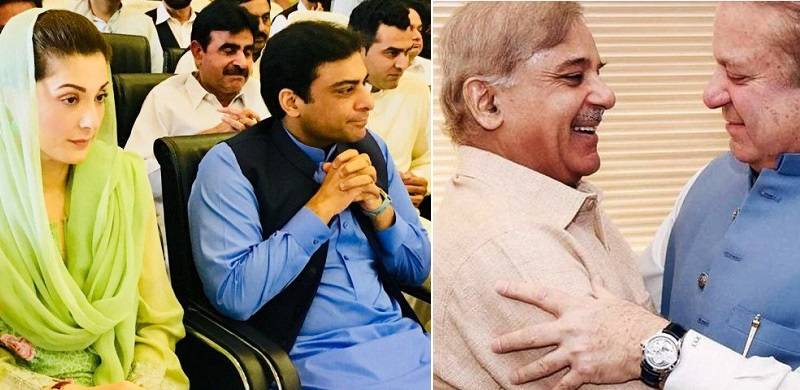

After one month of a province of 120 million people having been callously placed in a rudderless state by the questionable constitutional jugglery of its governor, the Punjab finally has a chief minister. But the combination of Shehbaz Sharif and Hamza Shehbaz as prime minister and chief minister has, as expected, evoked a wave of righteous indignation and hand-wringing, primarily by segments of the urban middle class, the “intelligentsia,” our educated elite and members of the chattering classes.

Whereas I personally believe that dynastic politics is an unhealthy tradition which impairs the growth of a robust and truly democratic political culture, I am also pragmatic enough to recognise that dynasties are intertwined in Pakistani politics and they cannot be flippantly wished away overnight.

Our political firmament is dotted with several family political enterprises, most prominent being the Bhutto-Zardaris, the Khans of Wali Bagh, the House of Mufti Mahmud, the Pirs of Pagara and the inheritors of Zahur Palace in Gujrat. But it is the PML-N, Pakistan’s most successful election fighting machine in recent history, which represents dynastic politics at its best, or its worst, as one perceives it. Largely due to the PML-N’s continued electoral success, the House of Sharif serves as the ultimate red rag to the opponents of the dynastic tradition.

But to understand why the Sharifs have seen fit to structure a family dynasty to run the PML-N, one needs to understand the peculiar dynamics of Pakistani politics.

For seven decades, politics in Pakistan has been buffeted by a series of violent storms, which chiefly arose as a result of four bouts of direct military rule and countless other incidents of indirect manipulation, engineering and interference by the establishment of the day. These destructive assaults wreaked havoc on the political system. A few examples drive the point home.

In the 1950s, genuine politicians like Nazimuddin, Suhrawardy, Nur ul Amin, Daultana, Qazi Isa, Ayub Khuhro and Khan Qayyum, etc. were disqualified under Ayub’s EBDO; in the 1960s, the Basic Democrats charade was introduced to perpetuate Ayub’s one-man rule through the creation of a new, and pliant, political class; in the early 1970s, Yahya’s regime miscalculated and played a dangerous game of politics which sidelined mainstream and pro-Pakistan Bengali politicians and handed an overwhelming victory to the Awami League; in the 1980s, Zia’s totalitarian regime at first ruthlessly suppressed political parties and then it dangerously undercut them through the party-less polls of 1985, which artificially propelled local bodies councilors, moneyed classes and dharra/biradari benefeciaries into the assemblies; and, finally, in the first decade of this century, Musharraf held a bogus referendum, blatantly contrived the manipulation of the 2002 elections, created yet another king’s party and engineered the Patriots splinter group in the PPP.

With such a sordid history of interference by shadowy forces, is it any surprise that our political order is hollow, artificial and, sadly, under-developed? The bitter truth is that when political parties are not allowed to grow organically over a sustained period of time, it is natural that their leadership will go down to first principles and batten the hatches by keeping control squarely within the family.

This truism squarely applies to the PML-N. When Nawaz Sharif first became prime minister in 1990, he selected Ghulam Hyder Wyne, a loyal non-family member, to replace him as Punjab chief minister. In April 1993, Nawaz Sharif’s government was unconstitutionally dismissed by president Ghulam Ishaq Khan and this spurred the ambitious speaker of the Punjab Assembly, Mian Manzoor Wattoo, to rebel and throw in his lot with the president. He split the Muslim League parliamentary party and replaced Ghulam Hyder Wyne as chief minister. The loss of the Punjab government was a grievous blow to Nawaz Sharif, and for this reason even the subsequent restoration of the National Assembly by the Supreme Court became a pyrrhic victory for him, since without control of the Punjab the federal government was unable to get its act in order and Nawaz Sharif soon exited the corridors of power.

The episode taught a bitter lesson to the Sharifs: in a country where the powerful establishment can easily turn the tables on an elected government by suborning the loyalties of MNAs and MPAs, it is essential to exercise control over the Punjab through a trusted and strong-willed chief minister – and perhaps only a family member can best fit the bill, at least until the political system gains sufficient maturity. Hence in 1997 the chief-ministership was entrusted to Shehbaz Sharif, and this ensured that no forward bloc or Manzoor Wattoo 2.0 emerged during the PML-N’s 1997-1999 stint in power.

The same formula was successfully adopted after the 2008 elections, with Shehbaz Sharif again becoming chief minister. During this period, the party suffered no split in its ranks – not even when the PPP’s federal government unconstitutionally imposed governor’s rule in the province in 2009. A formidable chief minister ensured that the PML-N’s provincial government performed strongly and this propelled the party’s return to power in the province at the 2013 elections. Even as a result of the controversial elections of 2018, the PML-N had emerged as the single largest party in the Punjab – before droves of independents were corralled by Jehangir Tareen into the PTI to allow it to form the provincial government.

Had Shehbaz Sharif not been the brother of Nawaz Sharif, he would neither have had a free hand to run the province, nor would he have retained the trust and support of the party leader. Our overall political tradition is of such a patently inorganic nature, as explained above, that no prime minister worth his salt can countenance a strong-man chief minister of Punjab, except perhaps if the latter is bound to him by ties of blood! Further, since only a strong-man chief minister can effectively administer a province the size of the Punjab, therefore the Nawaz-Shehbaz team made eminent sense and it delivered rich electoral dividends for the PML-N.

It is in this context that one should view Hamza Shehbaz’s election as the Punjab chief minister. Yes, at one level it does rankle to see a father-son duo occupy two of the most important elected positions in the country. But unless and until the democratic tradition takes root in the country over a few uninterrupted decades, and regular elections and orderly transitions of power become the norm, this manifestation of dynastic politics will remain par for the course.

Most importantly, the final arbiters of the vexed issue of dynastic politics should be the people of Pakistan. If they are put off by this show of in-your-face family rule, then at the next elections they can vote out the Sharifs once and for all! But if they vote the father-son duo back into power, then so be it, notwithstanding the anguished groans and pained protestations of the urban middle class and the Westernised elite.

Epilogue: From 2007 - 2017, the chief minister of Indian Punjab was Sardar Parkash Singh Badal. From 2009 – 2017, the deputy chief minister was his son, Sardar Sukhbir Singh Badal. Perhaps a father-son duo is sometimes not such an odd thing after all, at least in the Punjabi tradition!

Whereas I personally believe that dynastic politics is an unhealthy tradition which impairs the growth of a robust and truly democratic political culture, I am also pragmatic enough to recognise that dynasties are intertwined in Pakistani politics and they cannot be flippantly wished away overnight.

Our political firmament is dotted with several family political enterprises, most prominent being the Bhutto-Zardaris, the Khans of Wali Bagh, the House of Mufti Mahmud, the Pirs of Pagara and the inheritors of Zahur Palace in Gujrat. But it is the PML-N, Pakistan’s most successful election fighting machine in recent history, which represents dynastic politics at its best, or its worst, as one perceives it. Largely due to the PML-N’s continued electoral success, the House of Sharif serves as the ultimate red rag to the opponents of the dynastic tradition.

But to understand why the Sharifs have seen fit to structure a family dynasty to run the PML-N, one needs to understand the peculiar dynamics of Pakistani politics.

For seven decades, politics in Pakistan has been buffeted by a series of violent storms, which chiefly arose as a result of four bouts of direct military rule and countless other incidents of indirect manipulation, engineering and interference by the establishment of the day. These destructive assaults wreaked havoc on the political system. A few examples drive the point home.

In the 1950s, genuine politicians like Nazimuddin, Suhrawardy, Nur ul Amin, Daultana, Qazi Isa, Ayub Khuhro and Khan Qayyum, etc. were disqualified under Ayub’s EBDO; in the 1960s, the Basic Democrats charade was introduced to perpetuate Ayub’s one-man rule through the creation of a new, and pliant, political class; in the early 1970s, Yahya’s regime miscalculated and played a dangerous game of politics which sidelined mainstream and pro-Pakistan Bengali politicians and handed an overwhelming victory to the Awami League; in the 1980s, Zia’s totalitarian regime at first ruthlessly suppressed political parties and then it dangerously undercut them through the party-less polls of 1985, which artificially propelled local bodies councilors, moneyed classes and dharra/biradari benefeciaries into the assemblies; and, finally, in the first decade of this century, Musharraf held a bogus referendum, blatantly contrived the manipulation of the 2002 elections, created yet another king’s party and engineered the Patriots splinter group in the PPP.

With such a sordid history of interference by shadowy forces, is it any surprise that our political order is hollow, artificial and, sadly, under-developed? The bitter truth is that when political parties are not allowed to grow organically over a sustained period of time, it is natural that their leadership will go down to first principles and batten the hatches by keeping control squarely within the family.

This truism squarely applies to the PML-N. When Nawaz Sharif first became prime minister in 1990, he selected Ghulam Hyder Wyne, a loyal non-family member, to replace him as Punjab chief minister. In April 1993, Nawaz Sharif’s government was unconstitutionally dismissed by president Ghulam Ishaq Khan and this spurred the ambitious speaker of the Punjab Assembly, Mian Manzoor Wattoo, to rebel and throw in his lot with the president. He split the Muslim League parliamentary party and replaced Ghulam Hyder Wyne as chief minister. The loss of the Punjab government was a grievous blow to Nawaz Sharif, and for this reason even the subsequent restoration of the National Assembly by the Supreme Court became a pyrrhic victory for him, since without control of the Punjab the federal government was unable to get its act in order and Nawaz Sharif soon exited the corridors of power.

The episode taught a bitter lesson to the Sharifs: in a country where the powerful establishment can easily turn the tables on an elected government by suborning the loyalties of MNAs and MPAs, it is essential to exercise control over the Punjab through a trusted and strong-willed chief minister – and perhaps only a family member can best fit the bill, at least until the political system gains sufficient maturity. Hence in 1997 the chief-ministership was entrusted to Shehbaz Sharif, and this ensured that no forward bloc or Manzoor Wattoo 2.0 emerged during the PML-N’s 1997-1999 stint in power.

The same formula was successfully adopted after the 2008 elections, with Shehbaz Sharif again becoming chief minister. During this period, the party suffered no split in its ranks – not even when the PPP’s federal government unconstitutionally imposed governor’s rule in the province in 2009. A formidable chief minister ensured that the PML-N’s provincial government performed strongly and this propelled the party’s return to power in the province at the 2013 elections. Even as a result of the controversial elections of 2018, the PML-N had emerged as the single largest party in the Punjab – before droves of independents were corralled by Jehangir Tareen into the PTI to allow it to form the provincial government.

Had Shehbaz Sharif not been the brother of Nawaz Sharif, he would neither have had a free hand to run the province, nor would he have retained the trust and support of the party leader. Our overall political tradition is of such a patently inorganic nature, as explained above, that no prime minister worth his salt can countenance a strong-man chief minister of Punjab, except perhaps if the latter is bound to him by ties of blood! Further, since only a strong-man chief minister can effectively administer a province the size of the Punjab, therefore the Nawaz-Shehbaz team made eminent sense and it delivered rich electoral dividends for the PML-N.

It is in this context that one should view Hamza Shehbaz’s election as the Punjab chief minister. Yes, at one level it does rankle to see a father-son duo occupy two of the most important elected positions in the country. But unless and until the democratic tradition takes root in the country over a few uninterrupted decades, and regular elections and orderly transitions of power become the norm, this manifestation of dynastic politics will remain par for the course.

Most importantly, the final arbiters of the vexed issue of dynastic politics should be the people of Pakistan. If they are put off by this show of in-your-face family rule, then at the next elections they can vote out the Sharifs once and for all! But if they vote the father-son duo back into power, then so be it, notwithstanding the anguished groans and pained protestations of the urban middle class and the Westernised elite.

Epilogue: From 2007 - 2017, the chief minister of Indian Punjab was Sardar Parkash Singh Badal. From 2009 – 2017, the deputy chief minister was his son, Sardar Sukhbir Singh Badal. Perhaps a father-son duo is sometimes not such an odd thing after all, at least in the Punjabi tradition!