“First, when I started using drugs, it was because I was not able to sleep at night. I would hear echoes of the explosion and would see the faces of my two closest friends who were killed in the snooker club blast, and I carried them in my arms one by one to the ambulance, whose siren kept on pinching my ears, pushing my brain out of my eyes,” Haider* says, his eyes following his fingers, making circles on the soil. Teardrops fall in the circle he was making. He does not lift his head, nor his eyes; in fact, I find his eyes looking at mine only on a few occasions during the whole interview conducted on the 20th of February 2022.

He was never ready for the interview though I had insisted several times. But that day, he called me and asked me to meet him to share his story.

He had asked me to meet in one of the abandoned buildings on the north-eastern side of Hazara graveyard in Quetta. Except for a few that have roofs, these buildings are mostly just walls now. They are the remains of the storage houses used by army personnel during the severe drought in Balochistan in the 1990s. Now, they are a shelter for drug addicts.

I was sitting in front of Haider in one of them, interviewing him as a part of my case study on the Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) among the terrorism-affected Hazara community in Quetta, and he answered my question about why he had started drugs.

“To be honest, I never recovered after the incident. I survived the blast, but have I survived it?” he continues. It is one of the times he looks into my eyes. I think he is searching for an answer, but I don’t have any. He refers to the twin blasts in and near a snooker club on Alamdar Road Quetta on the 10th of January 2013, killing more than 80 people and injuring 120 others.

He was in the club, but he had miraculously survived the explosion, as he was sitting in one of the corners where a pillar had cushioned him. Two of his best friends were not fortunate enough, but Haider thinks otherwise.

As I didn’t have an answer to his question, I ask him another one, “When did you get married?”

“It was when I started behaving awkwardly. After the incident, I started having nightmares. I was not able to concentrate on myself and my job. Sleepless nights followed; absence from my duties multiplied. I took refuge in drugs; first hashish, then crystal meth. My family thought I was ripe to be married and a wife could mend my ways. For an instant, I also thought they were right. Therefore, I didn’t resist marrying the girl they chose for me. I don’t remember the year I was married. It may have been 5 or 6 years. I have three children now, but I have never quit drugs. I have thought of quitting several times but have not been able to do so. The guilt that followed my incapacity to quit after the marriage worsened the situation. Nightmares never stopped. My earnings could not make both ends meet as I had to spend a larger portion of it on drugs. Expenses kept increasing, especially after the birth of my children, tensions swelled, questions from my wife kept on irritating, and I used to answer them with violence. She no more asks any question. We now live like strangers under the same roof,” he says.

I had never thought in my wildest imagination that a person like Haider would be addicted to drugs. He was from my street. Though he was average in his studies, he was an avid football player. People in our area always believed he would be a star one day. I remember always playing in his team, not against him.

My next question is: “Have you ever tried to seek medical help for the stress and depression that you faced after the incident?”

My next question is: “Have you ever tried to seek medical help for the stress and depression that you faced after the incident?”

“I never realised I had any condition that required me to visit a doctor. I kept on hiding the nightmares and panic attacks. I didn’t like crying though I could not control it. I thought I was being a coward. What would people say if they knew I was afraid at night and that I cried? My condition worsened as I kept on increasing my dose. But I can never find permanent pleasure or relief. Anguish follows after the effect of the dose subsides.” He seems helpless.

“But it is not late even now; you can seek proper help from a professional psychiatrist or a rehabilitation center. Do you plan to seek such support in the future?” I ask encouragingly, expecting a positive answer from him.

“I don’t know if I can do it. I think I have come too far. There is no way I can go back. I can’t undo anything. I can’t undo my deeds, nor can I undo the incidents that have happened to me. I don’t think I will seek any such support, nor can I pay for such a luxury,” he concludes and looks at me once again. The dark patches around his eyes and pale complexion make him seem much older than 38 years. Life has been cruel to Haider, and the irony is that he is paying the price of surviving a bomb blast. While leaving him there, I wish that he would somehow seek professional help for his condition.

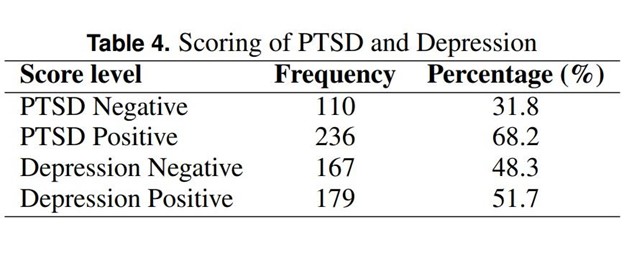

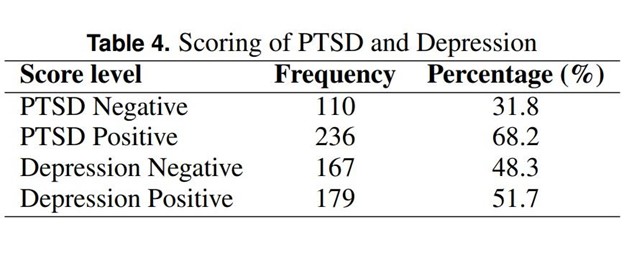

The story of Haider is an example of PTSD in a direct victim of the horrific terrorism that continued against the Hazara community in Quetta for two decades. In addition to 3,000 deaths and injuries and indescribable agony, it has influenced the mental health of the members of the community and their social psychology. As per a study, the Assessment of Psychological Status (PTSD and Depression) Among the Terrorism Affected Hazara Community in Quetta, Pakistan, which was conducted by medical researchers and published in the Cambridge Medicine Journal, there is a high prevalence of psychiatric disorders. Research findings show that 68.2% of Hazara youth in Quetta, mainly under the age of 25, are PTSD positive and 51.7% are depression positive.

Unfortunately, the health facilities to cater to the needs of people are almost non-existent. Even basic awareness regarding PTSD and depression is nowhere to be found, and most of the affected individuals do not realize that they need any sort of mental health support. The responsible authorities, on the other hand, have turned a deaf ear to the situation; or in most cases, they do not realize the gravity of the situation.

*Note: The name of the interviewee has been changed to protect his identity

The blog has been published in collaboration with Ravadar – a series that documents lives of religious minorities in Pakistan.

He was never ready for the interview though I had insisted several times. But that day, he called me and asked me to meet him to share his story.

He had asked me to meet in one of the abandoned buildings on the north-eastern side of Hazara graveyard in Quetta. Except for a few that have roofs, these buildings are mostly just walls now. They are the remains of the storage houses used by army personnel during the severe drought in Balochistan in the 1990s. Now, they are a shelter for drug addicts.

I was sitting in front of Haider in one of them, interviewing him as a part of my case study on the Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) among the terrorism-affected Hazara community in Quetta, and he answered my question about why he had started drugs.

“To be honest, I never recovered after the incident. I survived the blast, but have I survived it?” he continues. It is one of the times he looks into my eyes. I think he is searching for an answer, but I don’t have any. He refers to the twin blasts in and near a snooker club on Alamdar Road Quetta on the 10th of January 2013, killing more than 80 people and injuring 120 others.

He was in the club, but he had miraculously survived the explosion, as he was sitting in one of the corners where a pillar had cushioned him. Two of his best friends were not fortunate enough, but Haider thinks otherwise.

As I didn’t have an answer to his question, I ask him another one, “When did you get married?”

Research findings show that 68.2% of Hazara youth in Quetta, mainly under the age of 25, are PTSD positive and 51.7% are depression positive

“It was when I started behaving awkwardly. After the incident, I started having nightmares. I was not able to concentrate on myself and my job. Sleepless nights followed; absence from my duties multiplied. I took refuge in drugs; first hashish, then crystal meth. My family thought I was ripe to be married and a wife could mend my ways. For an instant, I also thought they were right. Therefore, I didn’t resist marrying the girl they chose for me. I don’t remember the year I was married. It may have been 5 or 6 years. I have three children now, but I have never quit drugs. I have thought of quitting several times but have not been able to do so. The guilt that followed my incapacity to quit after the marriage worsened the situation. Nightmares never stopped. My earnings could not make both ends meet as I had to spend a larger portion of it on drugs. Expenses kept increasing, especially after the birth of my children, tensions swelled, questions from my wife kept on irritating, and I used to answer them with violence. She no more asks any question. We now live like strangers under the same roof,” he says.

I had never thought in my wildest imagination that a person like Haider would be addicted to drugs. He was from my street. Though he was average in his studies, he was an avid football player. People in our area always believed he would be a star one day. I remember always playing in his team, not against him.

My next question is: “Have you ever tried to seek medical help for the stress and depression that you faced after the incident?”

My next question is: “Have you ever tried to seek medical help for the stress and depression that you faced after the incident?”“I never realised I had any condition that required me to visit a doctor. I kept on hiding the nightmares and panic attacks. I didn’t like crying though I could not control it. I thought I was being a coward. What would people say if they knew I was afraid at night and that I cried? My condition worsened as I kept on increasing my dose. But I can never find permanent pleasure or relief. Anguish follows after the effect of the dose subsides.” He seems helpless.

“But it is not late even now; you can seek proper help from a professional psychiatrist or a rehabilitation center. Do you plan to seek such support in the future?” I ask encouragingly, expecting a positive answer from him.

“I don’t know if I can do it. I think I have come too far. There is no way I can go back. I can’t undo anything. I can’t undo my deeds, nor can I undo the incidents that have happened to me. I don’t think I will seek any such support, nor can I pay for such a luxury,” he concludes and looks at me once again. The dark patches around his eyes and pale complexion make him seem much older than 38 years. Life has been cruel to Haider, and the irony is that he is paying the price of surviving a bomb blast. While leaving him there, I wish that he would somehow seek professional help for his condition.

The story of Haider is an example of PTSD in a direct victim of the horrific terrorism that continued against the Hazara community in Quetta for two decades. In addition to 3,000 deaths and injuries and indescribable agony, it has influenced the mental health of the members of the community and their social psychology. As per a study, the Assessment of Psychological Status (PTSD and Depression) Among the Terrorism Affected Hazara Community in Quetta, Pakistan, which was conducted by medical researchers and published in the Cambridge Medicine Journal, there is a high prevalence of psychiatric disorders. Research findings show that 68.2% of Hazara youth in Quetta, mainly under the age of 25, are PTSD positive and 51.7% are depression positive.

Unfortunately, the health facilities to cater to the needs of people are almost non-existent. Even basic awareness regarding PTSD and depression is nowhere to be found, and most of the affected individuals do not realize that they need any sort of mental health support. The responsible authorities, on the other hand, have turned a deaf ear to the situation; or in most cases, they do not realize the gravity of the situation.

*Note: The name of the interviewee has been changed to protect his identity

The blog has been published in collaboration with Ravadar – a series that documents lives of religious minorities in Pakistan.