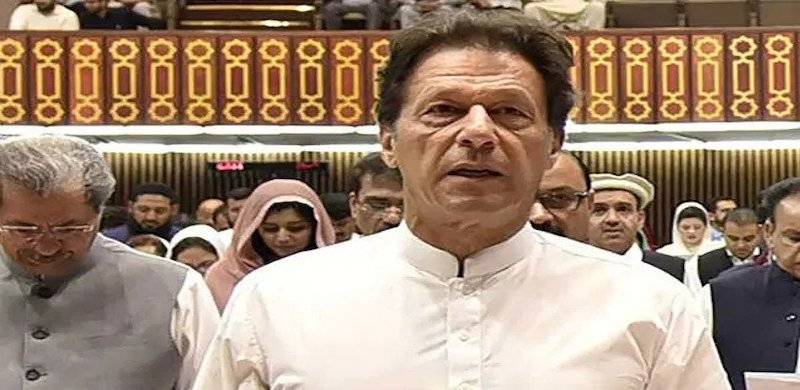

After making empty threats for months, the opposition has finally closed ranks. All its major parties have now agreed to bring a vote of no confidence (VoNC) motion against the PTI government -- in all likelihood against Prime Minister Imran Khan himself. While it is impossible to speak with full confidence given the murky nature of our politics, it seems very likely that the opposition has a sufficient number of pledges from within the ranks of PTI and allies for the motion to succeed.

Yet, it still remains a huge task for the opposition to turn these numbers into success and wrest the mantle of power from the hands of PTI. This is due to three factors:

First, the clauses around VoNC votes and its aftermath are highly under-defined in our constitution. Secondly, Imran Khan and PTI have shown an unmatched skill and viciousness in using institutions and the constitution and its gaps to their advantage through scorched-earth, no-holds barred tactics that put to shame even the highly unenviable history of parties like PPP and PML-N. It has shown this skill most clearly in its willingness to introduce presidential ordinances to suit highly partisan and narrow self-interests more than any other party in our history – even for much smaller gains.

With the very survival of its regime at stake, the government may even exceed its own track-record to-date in this regard in its famed 'cornered tigers' style -- especially given that the two key offices of the President and Speaker who have critical roles in the process are die-hard PTI loyalists.

Thirdly, the opposition is still not united on the issue of the post-no confidence motion set-up, with PML-N interested in immediate elections but PPP, PML-Q and reportedly the all-powerful establishment interested in the assembly completing its term till August 2023. Some opposition leaders say they will finalise these issues after the motion, reflecting deep divisions based on divergent interests. But since those divergent interests will remain intact even later, it cannot be assumed that their resolution will be easy, even then. Thus, we may soon be entering a period of high political turbulence which may result in a vicious and ugly power tussle that has the potential to create a serious constitutional crisis and pulls in the judiciary and even the establishment into the fray to resolve it. Let’s consider some of these scenarios.

The battle will cover the pre, during and post-motion phases, starting with the pre-motion phase battle for numbers. The constitution makes it mandatory for the assembly to vote on a no-confidence motion within 7 days of the submission of the opposition resolution for the motion signed by at least 20% members. The PTI will use every trick in the book to whittle down opposition numbers below the magic 172 figure through threats, inducements, arrests and perhaps even abductions. This battle may continue till the last moment, with fist-fights and gheraos in the assembly halls leading to the voting hall to deter the entry of PTI and allies’ members ignoring the party advice to stay away from assembly on the voting day. If the opposition manages to keep its numbers intact and manages to bring more than 172 members inside the voting hall, the next battle will be during voting and counting. Can the speaker stop PTI dissidents from voting or not allow their votes to be counted? Additionally, the Speaker has some discretion on rejecting votes on technical grounds related to the validity of the vote, as done during the no confidence vote against the Senate Chairperson. The matter is still languishing in courts on the issue of whether courts can pass judgments against parliamentary proceedings.

Finally, even if the opposition manages to score more than 172 votes all said and done, the battle will still not be fully over. The immediate issue then would be as to how quickly the opposition can come to an agreement on the way forward.

If it continues to struggle to come to an agreement, this could lead to huge political uncertainty. The immediate issue would relate to who is in charge. After Nawaz Sharif’s disqualification in 2017, Pakistan was without a Prime Minister for three days. But since the PML-N itself had a near-two-thirds majority, it was still quickly able to name a replacement. With much more fragmentation now and given the deep divisions within the opposition, it may take much longer now. Constitutional clause 94 says that the President may ask the Prime Minister to continue to hold office until the successor enters office. But this clause occurs in the constitution before clause 95 related to VoNC and so it is unclear if it covers VoNC scenarios too. Secondly, this lack of clarity is fuelled further by the fact that clause 95 explicitly says that the PM will cease to hold office once the note of no confidence passes.

Thirdly, clause 58 (1) mentions the process of a PM continuing in office only with regard to situations where a PM has resigned or dissolved the assembly but not with regard to court or assembly deseated PMs. President Mamnoon Hussain had not asked Nawaz Sharif to continue in office after his disqualification as he had ceased to be a member of the assembly. Whether a PM who has been voted out by assembly can continue in office is unclear. It is also unclear who will decide this matter: the President, assembly or courts.

But oddly enough, serious issues would emerge in either case. If a voted-out PM cannot continue in office and the opposition cannot come to an agreement for a prolonged period, this will give rise to serious political uncertainty and perhaps even a constitutional crisis. The situation will only be slightly better if an out-voted PM can continue in office. This would mean a highly furious Imran continuing in office while the opposition sorts out its differences and the Speaker and President using every trick possible in the books to prolong the transition. Article 58(2) says that the President may dissolve the assembly at their discretion if no other member commands a majority in a session called for this purpose.

The key words related to the President’s role are “may'' and “discretion”. How a partisan, die-hard President uses this discretion remains to be seen. There are also no constitutional time limits given on how soon this session has to be called, by whom and how its proceedings will be held. Thus, a partisan President and Speaker, acting on the orders of a furious Imran bent on destroying the system that kicked him out, may try to prolong it as much as they can. Obviously, this cannot be an endless process and moral and political pressure and court interventions will ultimately bring the game to an end. But the political uncertainty and damage could still be high. Much will also depend on the inclinations and quality of judgments of courts, and as always in Pakistan – the establishment.

The opposition can reduce the chances of such a scenario substantially, but not fully, by having a clear post-vote game plan even before it submits the VoNC resolution, enhancing its numbers as much as possible to safe, mischief-proof, levels and perhaps targeting the Speaker first to eliminate mischief from that office, though even doing that will run into many of the problems mentioned above. So the nation should be ready for much political turmoil and even a constitutional crisis in the coming months during a time period when it is already facing serious economic and security challenges.

What is certain is that Imran Khan is not going to submit gracefully to the democratic compulsions of a VoNC as leaders in the West do. He will try to cling to power as long and as viciously as he can. But ultimately, the people of Pakistan will ensure that he or his backers in any quarters no longer subvert democracy through ulterior moves.

Yet, it still remains a huge task for the opposition to turn these numbers into success and wrest the mantle of power from the hands of PTI. This is due to three factors:

First, the clauses around VoNC votes and its aftermath are highly under-defined in our constitution. Secondly, Imran Khan and PTI have shown an unmatched skill and viciousness in using institutions and the constitution and its gaps to their advantage through scorched-earth, no-holds barred tactics that put to shame even the highly unenviable history of parties like PPP and PML-N. It has shown this skill most clearly in its willingness to introduce presidential ordinances to suit highly partisan and narrow self-interests more than any other party in our history – even for much smaller gains.

With the very survival of its regime at stake, the government may even exceed its own track-record to-date in this regard in its famed 'cornered tigers' style -- especially given that the two key offices of the President and Speaker who have critical roles in the process are die-hard PTI loyalists.

Thirdly, the opposition is still not united on the issue of the post-no confidence motion set-up, with PML-N interested in immediate elections but PPP, PML-Q and reportedly the all-powerful establishment interested in the assembly completing its term till August 2023. Some opposition leaders say they will finalise these issues after the motion, reflecting deep divisions based on divergent interests. But since those divergent interests will remain intact even later, it cannot be assumed that their resolution will be easy, even then. Thus, we may soon be entering a period of high political turbulence which may result in a vicious and ugly power tussle that has the potential to create a serious constitutional crisis and pulls in the judiciary and even the establishment into the fray to resolve it. Let’s consider some of these scenarios.

With the very survival of its regime at stake, it may even exceed its own track-record to-date in this regard in its famed 'cornered tigers' style, especially given that the two key offices of the President and Speaker who have critical roles in the process are die-hard PTI loyalists.

The battle will cover the pre, during and post-motion phases, starting with the pre-motion phase battle for numbers. The constitution makes it mandatory for the assembly to vote on a no-confidence motion within 7 days of the submission of the opposition resolution for the motion signed by at least 20% members. The PTI will use every trick in the book to whittle down opposition numbers below the magic 172 figure through threats, inducements, arrests and perhaps even abductions. This battle may continue till the last moment, with fist-fights and gheraos in the assembly halls leading to the voting hall to deter the entry of PTI and allies’ members ignoring the party advice to stay away from assembly on the voting day. If the opposition manages to keep its numbers intact and manages to bring more than 172 members inside the voting hall, the next battle will be during voting and counting. Can the speaker stop PTI dissidents from voting or not allow their votes to be counted? Additionally, the Speaker has some discretion on rejecting votes on technical grounds related to the validity of the vote, as done during the no confidence vote against the Senate Chairperson. The matter is still languishing in courts on the issue of whether courts can pass judgments against parliamentary proceedings.

Finally, even if the opposition manages to score more than 172 votes all said and done, the battle will still not be fully over. The immediate issue then would be as to how quickly the opposition can come to an agreement on the way forward.

If it continues to struggle to come to an agreement, this could lead to huge political uncertainty. The immediate issue would relate to who is in charge. After Nawaz Sharif’s disqualification in 2017, Pakistan was without a Prime Minister for three days. But since the PML-N itself had a near-two-thirds majority, it was still quickly able to name a replacement. With much more fragmentation now and given the deep divisions within the opposition, it may take much longer now. Constitutional clause 94 says that the President may ask the Prime Minister to continue to hold office until the successor enters office. But this clause occurs in the constitution before clause 95 related to VoNC and so it is unclear if it covers VoNC scenarios too. Secondly, this lack of clarity is fuelled further by the fact that clause 95 explicitly says that the PM will cease to hold office once the note of no confidence passes.

Thirdly, clause 58 (1) mentions the process of a PM continuing in office only with regard to situations where a PM has resigned or dissolved the assembly but not with regard to court or assembly deseated PMs. President Mamnoon Hussain had not asked Nawaz Sharif to continue in office after his disqualification as he had ceased to be a member of the assembly. Whether a PM who has been voted out by assembly can continue in office is unclear. It is also unclear who will decide this matter: the President, assembly or courts.

But oddly enough, serious issues would emerge in either case. If a voted-out PM cannot continue in office and the opposition cannot come to an agreement for a prolonged period, this will give rise to serious political uncertainty and perhaps even a constitutional crisis. The situation will only be slightly better if an out-voted PM can continue in office. This would mean a highly furious Imran continuing in office while the opposition sorts out its differences and the Speaker and President using every trick possible in the books to prolong the transition. Article 58(2) says that the President may dissolve the assembly at their discretion if no other member commands a majority in a session called for this purpose.

The key words related to the President’s role are “may'' and “discretion”. How a partisan, die-hard President uses this discretion remains to be seen. There are also no constitutional time limits given on how soon this session has to be called, by whom and how its proceedings will be held. Thus, a partisan President and Speaker, acting on the orders of a furious Imran bent on destroying the system that kicked him out, may try to prolong it as much as they can. Obviously, this cannot be an endless process and moral and political pressure and court interventions will ultimately bring the game to an end. But the political uncertainty and damage could still be high. Much will also depend on the inclinations and quality of judgments of courts, and as always in Pakistan – the establishment.

The opposition can reduce the chances of such a scenario substantially, but not fully, by having a clear post-vote game plan even before it submits the VoNC resolution, enhancing its numbers as much as possible to safe, mischief-proof, levels and perhaps targeting the Speaker first to eliminate mischief from that office, though even doing that will run into many of the problems mentioned above. So the nation should be ready for much political turmoil and even a constitutional crisis in the coming months during a time period when it is already facing serious economic and security challenges.

What is certain is that Imran Khan is not going to submit gracefully to the democratic compulsions of a VoNC as leaders in the West do. He will try to cling to power as long and as viciously as he can. But ultimately, the people of Pakistan will ensure that he or his backers in any quarters no longer subvert democracy through ulterior moves.