parde me rahane doh

parda na uthao

parda jo uth gaya toh

bhed khul jayega

Allah meri tauba

Allah meri tauba

Shikar is a 1968 hindi film which has Dharmendra, Asha Parekh, Sanjeev Kumar, Rehman and Helen in lead roles.

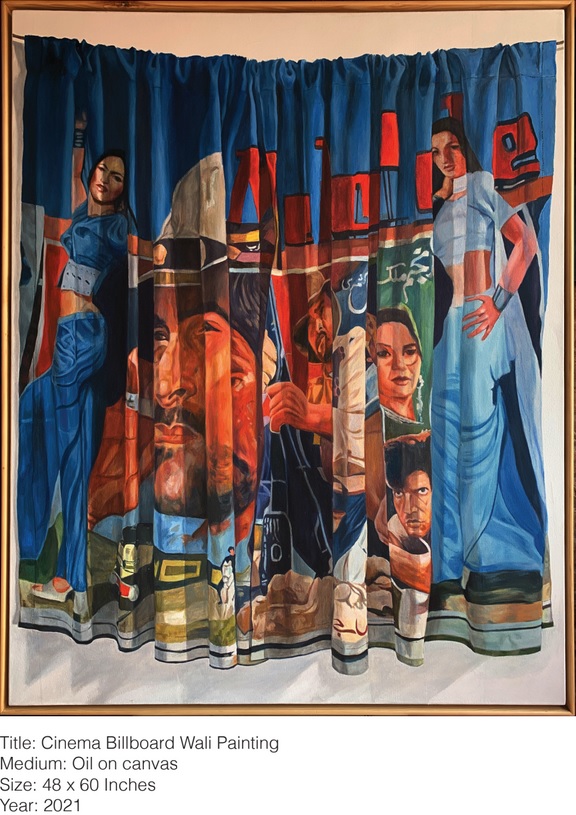

The film’s iconic song “Parde me rahane doh” opens with some people in fantasy Arabic costumes entering the stage. The man in the lead shows them some girls behind curtains. Each time, they show no interest. They arrive where Asha Parekh stands hidden. The music begins. Curtains keep falling and lifting from in front of her. The other girls also join her in the performance – both song and dance. Dharmendra appears there, playing a lawyer. He realises that she is the very girl who he had rescued from the accident site the other night. The sexualised nature of his gaze, the look he gives her, clearly depicts his urge to look beyond and behind the veil. Looking stems from Desire.

One can’t help but recall how revolutionary philosopher and psychiatrist Frantz Fanon describes European colonialists’ obsession with the veil as a desire to know the Other, to envision the concealed, to establish control over the Other, to dominate.

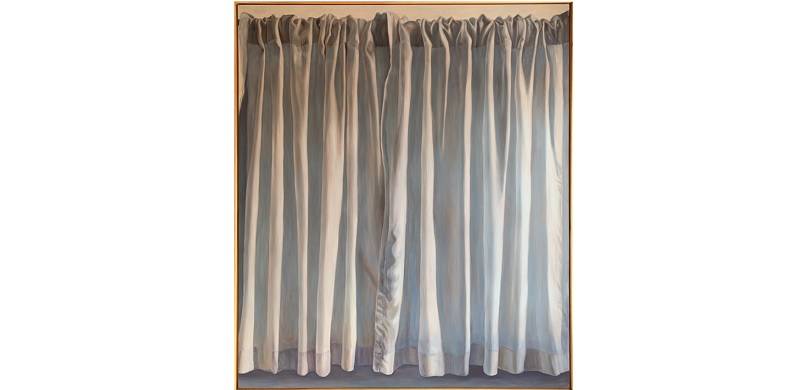

Curtains: from a mundane household item to a haunting metaphor, their allure envelops your spirit into their generous folds, and so does Ayaz Jokhio’s solo show that recently opened at the Canvas Gallery in Karachi, ironic as it may sound.

We speak here of the opening of a show titled “Curtained,” whereby the artist employs the curtain both as a symbolic and formal device to portray an exaggerated version of reality. The considerably large canvases with monstrous curtains painted on them confront the viewer at various levels: first and foremost the phenomenological experience that is perplexing and astonishing simultaneously, combined with an array of images from popular culture, news, entertainment and the internet undergoing visual distortion: ranging from the personal to the political, the subjective to the objective, the real to the seemingly real, the past to the present. The diversity and fluidity of his subject matter compliments the freedom that the artist seemingly enjoys in creating works that exude an element of freshness along with surprise, characterised by the inherent quality of initiating dialogue, be it his cynical iconic back portraits of popular personalities or the beguiling renditions of works by the great masters on auction, or his perfervid 99 self-portraits.

Jokhio, a meticulous image-maker, considers subject secondary as opposed to the visual impact that his work has on the viewer. For him, the visual impact is primary and accounts for viewer engagement and consumption, what he/she derives from what the artist intends.

The work titled “Jahazon wali painting” is a rendition of a bright blue curtain reminiscent of the sky with a configuration of five fighter jets moving across the picture plane to the right leaving behind contrails (condensation trails). In my opinion it might be referencing the transformative effects of an inflated sense of nationalism, especially in a South Asian context, from nation states to modern tribalism that provides nations with irrational justifications to assert power and dominance over the other.

Another striking curtain composition, “Imran khan wali painting,” imbues a heightened sense of melancholy and dejection. The folds of the curtain eliminate the serenity and perfection of the setting by deforming everything in the image, from the central figure, to the flags on either side, to the portrait of the founding father at the back - complete chaos to sum it up. The repetitive curtain ridges/creases in this particular work tend to shed light on the prevailing repetitive patterns/mistakes of the past. Irish clergyman Sean Brady said that there is always tension between the possibilities we aspire to and our wounded memories and the blunders of history. Or, as Anais Nin puts it: “And the very folds of the curtains contained secrets and sighs.”

“Deewar wali painting” is wholly solely a subjective rendition of a brick wall by Jokhio, strongly evoking heightened sensations of self-belief and determination. The artist has subverted the very rigidity of a brick wall structure: so that now it is not something to climb over, but to simply pass through. The piece is a testimony to the fact that while challenges and hurdles in life are inevitable, suffering defeat is optional.

“Windows XP wali painting” right away transposes the viewer to another realm, away from the presence of the work on display, to a realm of fantasy, dream and nostalgia. An image called “Bliss,” once encountered on screen as a default wallpaper is today being viewed as a curtain fabric in a painting. It strongly reinforces and reiterates notions of decreasing utility overtime. Something of utmost utility today will lose its significance tomorrow and be labelled redundant or outdated: mortality is intrinsic to human life and the things associated with it.

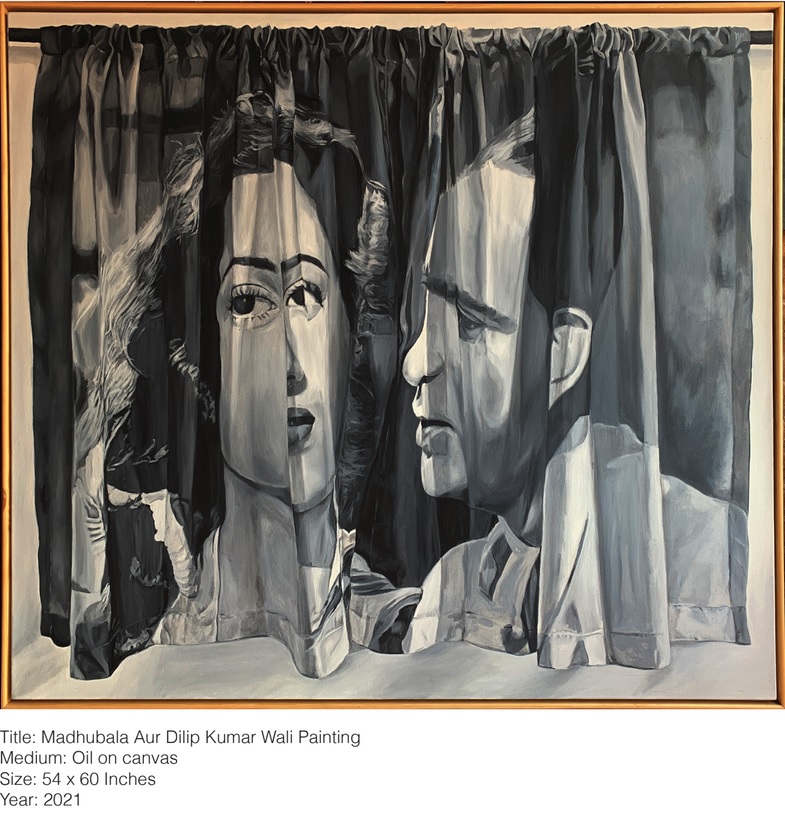

It wouldn’t be fair to conclude it all without making mention of the piece that clearly stood out: the black and white curtain that depicts Dilip Kumar and Madhubala, one of the most-loved couples onscreen in the 1950s era of Bollywood. Having romanced each other in films such as Mughal-e-Azam, Amar and Sangdil, the actors were also in love in real life. However, it failed to culminate in marriage. Madhubala, considered to be the epitome of beauty, was a distressed soul who failed in love and was betrayed by life. She died at a young age of 36, hence remembered as “The Beauty with Tragedy.”

Nevertheless, Ayaz Jokhio celebrates her life. He believes that the tragedy of life is not death, but what we let die inside us, while we live.

Note: The show continues till 14 January 2022.

Talal Faisal Ismaili is an artist based in Lahore