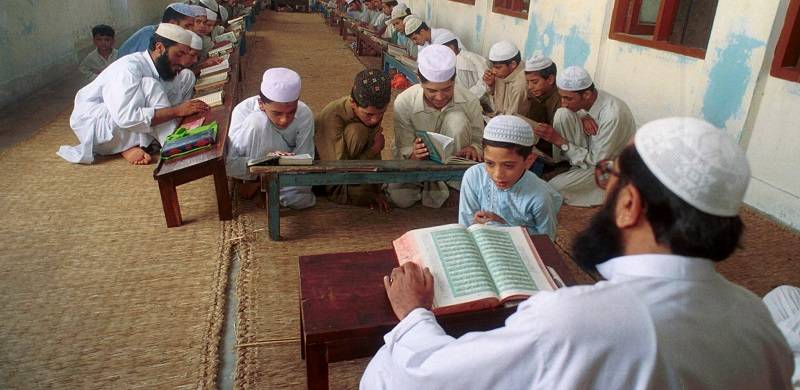

Numbering more than 30,000 madrassahs, they often serve free education, food and sometimes shelter to around 4 million poor children across Pakistan: Major General Asif Ghafoor told reporters in 2019. 27,000 of these are registered with the government – 5,000 of which are now registered under madrassah reforms since 2019 – while the rest operate illegally. Given the current state of government-run primary and secondary educational institutes, madrassahs provide the most promising source of education for low-income families, besides for many the only supposedly indispensable sacred and safe space to receive the best religious and Quranic education. It its essence, a madrassah is a time-tested institution that has served societies. Not too many centuries ago, the madrassah would be producing some of the greatest minds and leaders.

Former President General Pervez Musharaf in 2002 even called madrassahs “Pakistan’s biggest network of NGOs.” Religious seminaries in Pakistan are privately funded by individuals, political parties, and foreign states like Saudi Arabia. They often remain outside the control of the government. In an attempt to adapt madrassahs to a modern education system and regulate their operations, many reforms are now promulgated to implement the Single National Curriculum on registered religious seminaries. However, no regulatory body or system of accountability is established to prevent cases of child sexual abuse by clerics and people holding religious titles.

The report entitled “Cruel Number 2020” by Sahil revealed a 17% increase in child sexual abuse in 2020. It showed that as many as eight children are abused daily in Pakistan. The majority of cases reported included a victim in the age bracket of 6-15. Children as young as 0-5 years were also reported being sexually abused, nevertheless. Similar to 2019 statistics reported in “Cruel Numbers 2019” by Sahil, most of the perpetrators were acquaintances and from the category of service providers including maulvi, teacher, doctor and police.

Child molestation and physical abuse by religious and spiritual leaders in religious institutes is a pervasive, longstanding and neglected global issue. The patterns of child sexual abuse by clerics with justifications of abuse, suppression of disclosure, seeing child sexual abuse as a ‘private matter’ and a taboo subject, and religiously-oriented grooming are similar to those observed by the Boston Globe investigation of priests in US and – recently by a report – in France. According to a 2016 study, “Religion in child sexual abuse forensic interviews,” the process of abuse often begins by targeting poor and vulnerable children. They gain the trust of the child by giving attention and gifting them chocolates or other incentives. This is followed by grooming the child through actions that clerics justify by imposing their authority and/or due to peer pressure. Then comes a time when the child encounters physical or sexual abuse.

The case of ‘Mufti’ Aziz-ur-Rehman is one of many incidents that are regularly reported in newspapers, except that this incident was videotaped and leaked – causing an uproar on digital platforms that forced several clerics to make public statements. However, probing cases of child sexual abuse within the madrassah system in Pakistan is a thorny issue due to strong clerical ties with the police and support from revered political figures and individuals. In a 2017 Independent UK article on Islamic schools in Pakistan, Manizeh Bano – executive director of Sahil – shared that 359 cases of child molestation by religious clerics and officials caught media attention over the past 10 years, which is “barely the tip of the iceberg.” These perpetrators often have greater fan-following, albeit enjoy impunity due to flaws in criminal justice system.

The Gap Analysis conducted by Legal Aid Society (LAS) in 2020 showed that on average it takes 1.3 months to report rape and sodomy cases. Although only few cases of child sexual abuse by clerics ever get reported due to intimidation caused by religious institutes, research shows that delay in reporting is used as a tactic by defense counsels to dent the prosecution’s case. Any attempt made to expose incidents of child molestation by clerics faces harsh criticism from religious and political figures who discredit these instances as “attempts to malign the religion, seminaries and clerics” according to Independent UK; hence, often causing delay in/withdrawal from the case . A senior official in a ministry also stated to an Associate Press (AP) investigation that “among the weapons they [clerics] use to frighten their critics is a controversial blasphemy law that carries a death penalty in the case of a conviction.”

There is a dire need to take strict measures to prevent cases of child sexual and physical abuse in religious institutes. First and foremost, all religious leaders must realise and acknowledge the pervasiveness of the issue. They must prioritise creating and maintaining madrassa a child safety institute. For this purpose, the Ittehad-e-Tanzeemat-Madaris, Interior Ministry and Ministry of Human Rights should join hands and establish an independent special committee aimed at creating a highly organised and efficient system. The hiring of religious teachers should remain a transparent and rigorously scrutinised processes. This could be done via creating a local governance system within the madrassah network, which should remain accountable to a special committee. So far, there has been a ubiquitous phenomenon where the upbringing and nurturing of children – especially from the marginalised and neglected areas of our society – is contingent on ill-trained, psychologically impaired and sexually frustrated teachers at ill-equipped religious institutions teaching morality and Islamic values. Regardless of their contested educational and unclear ethical standards, these madrassah teachers must be held accountable to the committee, judiciary and esteemed religious leaders.

The committee should act as a mediating force between the law-enforcement agencies, the judiciary and the stakeholders within the madrassah system ensuring that religious clerics accused of child sexual abuse must be blacklisted and prohibited to teach in any institute ever across Pakistan, if and when proven guilty. They must ensure that once reported, the family of a survivor faces no backlash and/or discrimination or intimidation from any religious leaders, police or judiciary. The committee should also be held responsible for the implementation of protection laws for the survivor and the family.

For this purpose, capacity-building training for pre- and in-service police and judges should be conducted and their performance – especially for cases of child sexual abuse – must strictly be regulated. To improve competency and gender-sensitiveness of GBV investigating officers (IOs) and trial judges, training should be conducted that includes definition and ingredients of the crime of rape under the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC). Emphasis should be put on identifying relevant PPC sections (according to amended laws and acts) and conversation on prevalent victim-blaming should be emphasised. The training should also underline the medium- to long-term impact of rape and lay stress on the need for adopting a victim-centric approach.

We often lament and curse these predators and the government for persistently failing to protect our young ones, but after the hype falls, we become indifferent to it. It is time that the government takes strict measures to regulate the madrassah network and extend its support to survivors and their families. The government should not wait for another ‘Mufti’ Aziz-ur-Rehman to reappear. A public inquiry commission must be put into place immediately to ensure absolute safety of children and revive the sacredness of religious institutes.

Former President General Pervez Musharaf in 2002 even called madrassahs “Pakistan’s biggest network of NGOs.” Religious seminaries in Pakistan are privately funded by individuals, political parties, and foreign states like Saudi Arabia. They often remain outside the control of the government. In an attempt to adapt madrassahs to a modern education system and regulate their operations, many reforms are now promulgated to implement the Single National Curriculum on registered religious seminaries. However, no regulatory body or system of accountability is established to prevent cases of child sexual abuse by clerics and people holding religious titles.

The report entitled “Cruel Number 2020” by Sahil revealed a 17% increase in child sexual abuse in 2020. It showed that as many as eight children are abused daily in Pakistan. The majority of cases reported included a victim in the age bracket of 6-15. Children as young as 0-5 years were also reported being sexually abused, nevertheless. Similar to 2019 statistics reported in “Cruel Numbers 2019” by Sahil, most of the perpetrators were acquaintances and from the category of service providers including maulvi, teacher, doctor and police.

Child molestation and physical abuse by religious and spiritual leaders in religious institutes is a pervasive, longstanding and neglected global issue. The patterns of child sexual abuse by clerics with justifications of abuse, suppression of disclosure, seeing child sexual abuse as a ‘private matter’ and a taboo subject, and religiously-oriented grooming are similar to those observed by the Boston Globe investigation of priests in US and – recently by a report – in France. According to a 2016 study, “Religion in child sexual abuse forensic interviews,” the process of abuse often begins by targeting poor and vulnerable children. They gain the trust of the child by giving attention and gifting them chocolates or other incentives. This is followed by grooming the child through actions that clerics justify by imposing their authority and/or due to peer pressure. Then comes a time when the child encounters physical or sexual abuse.

The case of ‘Mufti’ Aziz-ur-Rehman is one of many incidents that are regularly reported in newspapers, except that this incident was videotaped and leaked – causing an uproar on digital platforms that forced several clerics to make public statements. However, probing cases of child sexual abuse within the madrassah system in Pakistan is a thorny issue due to strong clerical ties with the police and support from revered political figures and individuals. In a 2017 Independent UK article on Islamic schools in Pakistan, Manizeh Bano – executive director of Sahil – shared that 359 cases of child molestation by religious clerics and officials caught media attention over the past 10 years, which is “barely the tip of the iceberg.” These perpetrators often have greater fan-following, albeit enjoy impunity due to flaws in criminal justice system.

The Gap Analysis conducted by Legal Aid Society (LAS) in 2020 showed that on average it takes 1.3 months to report rape and sodomy cases. Although only few cases of child sexual abuse by clerics ever get reported due to intimidation caused by religious institutes, research shows that delay in reporting is used as a tactic by defense counsels to dent the prosecution’s case. Any attempt made to expose incidents of child molestation by clerics faces harsh criticism from religious and political figures who discredit these instances as “attempts to malign the religion, seminaries and clerics” according to Independent UK; hence, often causing delay in/withdrawal from the case . A senior official in a ministry also stated to an Associate Press (AP) investigation that “among the weapons they [clerics] use to frighten their critics is a controversial blasphemy law that carries a death penalty in the case of a conviction.”

There is a dire need to take strict measures to prevent cases of child sexual and physical abuse in religious institutes. First and foremost, all religious leaders must realise and acknowledge the pervasiveness of the issue. They must prioritise creating and maintaining madrassa a child safety institute. For this purpose, the Ittehad-e-Tanzeemat-Madaris, Interior Ministry and Ministry of Human Rights should join hands and establish an independent special committee aimed at creating a highly organised and efficient system. The hiring of religious teachers should remain a transparent and rigorously scrutinised processes. This could be done via creating a local governance system within the madrassah network, which should remain accountable to a special committee. So far, there has been a ubiquitous phenomenon where the upbringing and nurturing of children – especially from the marginalised and neglected areas of our society – is contingent on ill-trained, psychologically impaired and sexually frustrated teachers at ill-equipped religious institutions teaching morality and Islamic values. Regardless of their contested educational and unclear ethical standards, these madrassah teachers must be held accountable to the committee, judiciary and esteemed religious leaders.

The committee should act as a mediating force between the law-enforcement agencies, the judiciary and the stakeholders within the madrassah system ensuring that religious clerics accused of child sexual abuse must be blacklisted and prohibited to teach in any institute ever across Pakistan, if and when proven guilty. They must ensure that once reported, the family of a survivor faces no backlash and/or discrimination or intimidation from any religious leaders, police or judiciary. The committee should also be held responsible for the implementation of protection laws for the survivor and the family.

For this purpose, capacity-building training for pre- and in-service police and judges should be conducted and their performance – especially for cases of child sexual abuse – must strictly be regulated. To improve competency and gender-sensitiveness of GBV investigating officers (IOs) and trial judges, training should be conducted that includes definition and ingredients of the crime of rape under the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC). Emphasis should be put on identifying relevant PPC sections (according to amended laws and acts) and conversation on prevalent victim-blaming should be emphasised. The training should also underline the medium- to long-term impact of rape and lay stress on the need for adopting a victim-centric approach.

We often lament and curse these predators and the government for persistently failing to protect our young ones, but after the hype falls, we become indifferent to it. It is time that the government takes strict measures to regulate the madrassah network and extend its support to survivors and their families. The government should not wait for another ‘Mufti’ Aziz-ur-Rehman to reappear. A public inquiry commission must be put into place immediately to ensure absolute safety of children and revive the sacredness of religious institutes.