The eventual return of the Taliban to the helm at Kabul may be described as “sweeping,” but it cannot be characterized as something appearing out of the thin air. A thorough dissection of Taliban military strategy right from the day way back in 2001 when B-52 bombers began bombing their regime out of power till the Taliban 2.0’s triumphant walk-back in Kabul, reveals the grand strategy followed by the group. However, ideological differences and the traditional appearance of a Taliban fighter tend to tamper our analytical ability to understand the Taliban. The ideological and appearance-related biases led to the misjudgement of the Taliban military wisdom and their acumen as a political force.

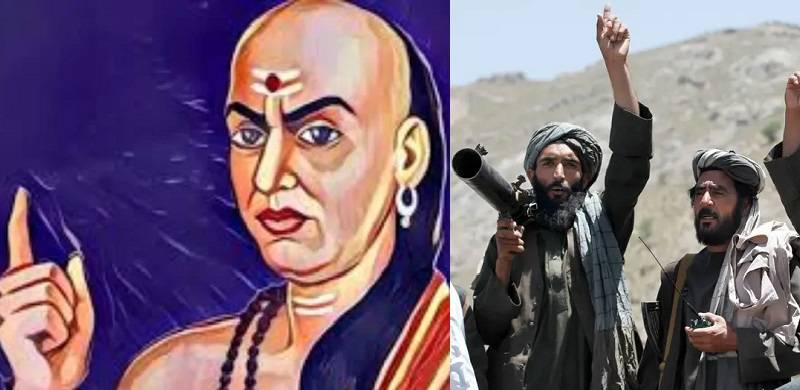

Seen in hindsight, the Taliban success in reclaiming control over Afghanistan after 20 years owes to their sophisticated strategic moves underpinned by the politico-military wisdom of Chanakya (c. 300 BC). Perhaps, they may have never read the treatise Arthashastra (“The Science of Material Gain”) or even heard of its author Chanakya, better known as Kautilya – a great political thinker born and educated in what is today Pakistan: the university town of present-day Taxila. Serving as chief advisor, he helped Chandragupta establish a vast empire in the Indian Subcontinent. Unfortunately, the great military strategist and political thinker remains disowned in the country of his birth, Pakistan, where official history is dated from the invasion of Sindh by the Arab general Muhammad bin Qasim in the 8th century AD. Anything preceding the 711-12, is considered non-kosher.

Tellingly, Taliban’s return to power testifies to timelessness and efficacy of Kautilyan political and military philosophy penned down two millennia ago. In his magnum opus, he advises against fighting a stronger enemy. Acting on this pragmatic advice, Taliban melted away when the most powerful state unleashed its firepower against them in 2001. The US war machine was able to dislodge the regime from power, but it was the Kautilyan counsel that kept Taliban in this game of thrones. Following their fall, the group regrouped and resorted to an asymmetric fight against the US/NATO forces.

Further, in the run-up to their bloodless takeover of Kabul, the Taliban made the best use of another military-takeover tactic employed by Kautilya to overthrow the Nanda dynasty. According to a legend, he overheard a woman chiding her son for burning his fingers by trying to eat from the middle of a plate of hot rice. The mother told her son that he was supposed to start eating from the edges, where the rice was cooler. Kautilya was quick to realise his mistake of attacking the Nanda capital without subduing the border regions. Subsequently, he and his master Chandragupta recalibrated their military strategy and started to conquer and consolidate the peripheral regions before they finally captured the capital.

The trajectory of the Taliban’s military strategy since the last couple of years, specifically in the wake of their peace deal with the US, indicates that the group had been taking over peripheral swathes of territory in northern and southern Afghanistan – in precisely the Kautilyan way that we described earlier. Once the rural areas and bordering urban centres submitted to direct Taliban control, the fall of Kabul was only a matter of ‘when,’ not ‘if' – especially in the absence of an American security umbrella.

Moreover, Kautilya suggests the deployment of soft and conciliatory means like material and political inducements as a policy to win over opponents. This is exactly what the Taliban did over the years, especially in northern Afghanistan. By capitalising on dissatisfaction over the misgovernance of successive Afghan governments, the Taliban have been able to make inroads and co-opt local leaders in the north. This policy explains the presence of a number of Uzbeks, Tajiks, Turkmen and Hazaras amongst the rank and file of the otherwise Pashtun-dominated group.

Last but not least, the Arthashastra seems to have been a great guide to understanding the strategy of the Taliban when it comes to battle of narratives. Kautilya emphasises that an enemy's people should be frightened and overawed by creating the mirage of omnipotence, omnipresence and divine legitimacy. In this regard, Taliban’s ability to sustain a 20-year-long guerrilla struggle against the US/NATO forces; military capability to execute guerrilla attacks across the country; organisational resilience despite leadership changes and the religio-nationalist narrative branding the US as an occupying power and the Afghan government as its puppets were all in tune with the above advice.

In sum, the politico-military plan pursued by Taliban appears as if it were inspired by Kautilyan thought, regardless of whether they were aware of this ancient strategist.

More importantly, Kautilya offers some pearls of wisdom on governance too, for the kind consideration of the future Taliban-led government. Kautilya says that in the happiness of his subjects lies the ruler's happiness; in their welfare his welfare; whatever pleases himself he shall not consider as good, but whatever pleases his subjects he shall consider as good. Ignoring this seminal Kautilyan advice on running a country to the benefit of its people may turn out to be the undoing of Taliban.

Today, Afghanistan has changed. It is a youth-driven country and better connected with itself and with the outside world. Social media has enabled the Afghan youth and civil society to express themselves and organise. The Afghan diaspora has come to act as the amplifier for the voices of dissent in the country of their origin. If the Taliban 2.0 want to consolidate their regime 2.0, these altered circumstances vociferously call for respect towards civil liberties, inclusive politics, good governance and cooperation with the international community.

The writer is an Islamabad-based columnist pursuing his PhD in International Relations at the Department of International Relations, National University of Modern Languages (NUML), Islamabad

Seen in hindsight, the Taliban success in reclaiming control over Afghanistan after 20 years owes to their sophisticated strategic moves underpinned by the politico-military wisdom of Chanakya (c. 300 BC). Perhaps, they may have never read the treatise Arthashastra (“The Science of Material Gain”) or even heard of its author Chanakya, better known as Kautilya – a great political thinker born and educated in what is today Pakistan: the university town of present-day Taxila. Serving as chief advisor, he helped Chandragupta establish a vast empire in the Indian Subcontinent. Unfortunately, the great military strategist and political thinker remains disowned in the country of his birth, Pakistan, where official history is dated from the invasion of Sindh by the Arab general Muhammad bin Qasim in the 8th century AD. Anything preceding the 711-12, is considered non-kosher.

Tellingly, Taliban’s return to power testifies to timelessness and efficacy of Kautilyan political and military philosophy penned down two millennia ago. In his magnum opus, he advises against fighting a stronger enemy. Acting on this pragmatic advice, Taliban melted away when the most powerful state unleashed its firepower against them in 2001. The US war machine was able to dislodge the regime from power, but it was the Kautilyan counsel that kept Taliban in this game of thrones. Following their fall, the group regrouped and resorted to an asymmetric fight against the US/NATO forces.

Kautilya suggests the deployment of soft and conciliatory means like material and political inducements as a policy to win over opponents. This is exactly what the Taliban did over the years, especially in northern Afghanistan

Further, in the run-up to their bloodless takeover of Kabul, the Taliban made the best use of another military-takeover tactic employed by Kautilya to overthrow the Nanda dynasty. According to a legend, he overheard a woman chiding her son for burning his fingers by trying to eat from the middle of a plate of hot rice. The mother told her son that he was supposed to start eating from the edges, where the rice was cooler. Kautilya was quick to realise his mistake of attacking the Nanda capital without subduing the border regions. Subsequently, he and his master Chandragupta recalibrated their military strategy and started to conquer and consolidate the peripheral regions before they finally captured the capital.

The trajectory of the Taliban’s military strategy since the last couple of years, specifically in the wake of their peace deal with the US, indicates that the group had been taking over peripheral swathes of territory in northern and southern Afghanistan – in precisely the Kautilyan way that we described earlier. Once the rural areas and bordering urban centres submitted to direct Taliban control, the fall of Kabul was only a matter of ‘when,’ not ‘if' – especially in the absence of an American security umbrella.

Moreover, Kautilya suggests the deployment of soft and conciliatory means like material and political inducements as a policy to win over opponents. This is exactly what the Taliban did over the years, especially in northern Afghanistan. By capitalising on dissatisfaction over the misgovernance of successive Afghan governments, the Taliban have been able to make inroads and co-opt local leaders in the north. This policy explains the presence of a number of Uzbeks, Tajiks, Turkmen and Hazaras amongst the rank and file of the otherwise Pashtun-dominated group.

Ignoring this seminal Kautilyan advice on running a country to the benefit of its people may turn out to be the undoing of Taliban

Last but not least, the Arthashastra seems to have been a great guide to understanding the strategy of the Taliban when it comes to battle of narratives. Kautilya emphasises that an enemy's people should be frightened and overawed by creating the mirage of omnipotence, omnipresence and divine legitimacy. In this regard, Taliban’s ability to sustain a 20-year-long guerrilla struggle against the US/NATO forces; military capability to execute guerrilla attacks across the country; organisational resilience despite leadership changes and the religio-nationalist narrative branding the US as an occupying power and the Afghan government as its puppets were all in tune with the above advice.

In sum, the politico-military plan pursued by Taliban appears as if it were inspired by Kautilyan thought, regardless of whether they were aware of this ancient strategist.

More importantly, Kautilya offers some pearls of wisdom on governance too, for the kind consideration of the future Taliban-led government. Kautilya says that in the happiness of his subjects lies the ruler's happiness; in their welfare his welfare; whatever pleases himself he shall not consider as good, but whatever pleases his subjects he shall consider as good. Ignoring this seminal Kautilyan advice on running a country to the benefit of its people may turn out to be the undoing of Taliban.

Today, Afghanistan has changed. It is a youth-driven country and better connected with itself and with the outside world. Social media has enabled the Afghan youth and civil society to express themselves and organise. The Afghan diaspora has come to act as the amplifier for the voices of dissent in the country of their origin. If the Taliban 2.0 want to consolidate their regime 2.0, these altered circumstances vociferously call for respect towards civil liberties, inclusive politics, good governance and cooperation with the international community.

The writer is an Islamabad-based columnist pursuing his PhD in International Relations at the Department of International Relations, National University of Modern Languages (NUML), Islamabad