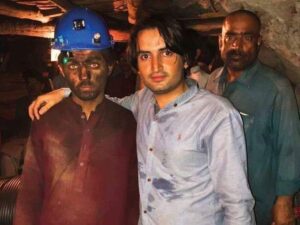

Balochistan’s black gold workers are forced to work under tough condition with government’s indifference. The miners toil in the mines all day, but are paid a little amount at the end of the day — which is insufficient to meet their needs.

It is true that no one dies from hard work, but when a labourer is made to work like an animal, the hours of age begin to decline. When medical facilities are not available, diseases settle in permanently.

Getting coal out of a mine that is miles deep is like seeing the angel of death. At any moment, a landslide can strike a worker. The workers who escape accidents do not live long either.

Coarse particles of coal pass through their mouth and nostrils and form a kind of mine inside the worker. The lungs, kidneys and heart gradually stop working.

“By law, the coal worker is given hot water after finishing work. They must take a bath but the owners often do not provide it,” a mines inspector of Duki district in Balochistan said. “They do not even provide clean drinking water to the poor laborers.”

Duki district has the highest number of coal mines, but unfortunately the highest number of deaths too.

“This year the number of people killed in coal mines has risen to 20 while in 2019, 40 miners were killed in coal mine accidents,” the mines inspector said.

According to the the Balochistan Mines Association, more than 1,300 miners in Pakistan have died in coal mine explosions, landslides, and various accidents over the past 20 years.

Located in the middle of the Bolan Valley, Mach is known for its historical, cultural, climatic and mineral status. The mountains of Mach are rich in mineral resources, especially coal.

“I have been working in the coal mines here since 2004,” a local miner Khairul Bashar said. “My leg was broken in an accident in 2018.”

He said there is no hospital or health facility to provide medical care to the miners.

“Initially the contractor spent some money on the treatment but since then I have been getting my treatment done without any help and on my own,” Bashar said.

He terms mining a very dangerous job, as people become disabled or die in mining incidents.

Naseeb Ullah started working in the mines after completing his matriculation three years ago. He could not continue his education due to poor financial situation of his family.

“I earn Rs. 2000 as wages every week for working in the coal mine,” he said, and insisted that due to lack of safety protocols and health facilities, the threat of loss of life inside the coal mines is high.

The British started extracting coal from Balochistan back in the 1850s. They built a railway track to facilitate transport. These tracks in the Bolan Pass are still in use. But the coal industry has come a long way since then in terms of production. There are five major coalfields operating at the moment: Mach, Shahrag, Duki, Chamalang, and Quetta. According to one estimate, Balochistan has over 2.2 billion tonnes of coal reserves.

The mining operation across the province are also massive, with at least 15,000 tonnes of coal produced daily. The coal sells for an average Rs. 15,000 per tonne. Balochistan has more than 3,000 registered coalmines where over 40,000 miners work.

Mach coal stock runs the energy wheel across the country. There are about 500 coalmines in area and 2,000 tonne of coal is produced here every day.

According to coal mine contractors, the government receives billions of rupees in taxes annually from the Mach area alone.

“I have been working in the coal mine business for the last 20 years,” Gul Baraan, the local contractor of a coalmine, said. “We pay Rs. 500 per tonne of coal to the government as sales tax. In addition, we pay royalty tax of Rs. 130 per tonne to the government. While, Rs. 10 per tonne labour tax is also paid.”

This amounts to nearly Rs. 1.3 million in daily taxes for the 2,000-tonne coal output from Mach.

Baraan said that despite all the valuable addition to government’s tax collection, there is no government hospital or any other facility provided in the area.

“Mach is like a gold mine, but it is still the most backward area despite making billions of rupees in profits,” he said.

“We, the contractors, make our own arrangements for the welfare of the workers, without any official assistance,” Baraan claimed.

He said there are many problems in Mach.

“I have been working in the coal mine business for the last 20 years,” Gul Baraan, the local contractor of a coalmine, said. “We pay Rs. 500 per tonne of coal to the government as sales tax. In addition, we pay royalty tax of Rs. 130 per tonne to the government. While, Rs. 10 per tonne labour tax is also paid.”

“Even today, there is no hospital in Mach,” Baraan said. “Only one dispensary is available for the entire population.”

If there is an accident at the mines, the victims have to be taken to a hospital in Quetta 66 kilometres away.

“As most of the facilities are not available in Bolan, many labourers succumb to injuries while they are being taken to hospitals of Quetta,” Baraan said.

On 20 March, a blast took place inside a coalmine at Digari Margat, which is 60 kilometres away from Quetta, as labourers were working inside.

According to Balochistan chief mine inspector Shafqat Fayyaz, the explosion took place due to the presence of methane gas in a mine in Digari area. The incident took lives of seven labourers and left three miners injured.

The presence of methane gas in a mine has been the most common reason for such incidents in mines, Fayyaz said.

This is not the first time that such an incident has taken many lives inside a coalmine.

In the past 10 years, 570 miners were killed and hundreds of others injured in Balochistan. In 30 incidents in 2019 alone, 86 miners were killed and 35 injured. Another 28 miners were killed in Degari, Marwar, and Sanjdi areas on the outskirts of Quetta. Another 58 miners died in other areas.

“Accidents in coal mines occur due to lack of precautionary measures and lack of facilities,” National Commission for Human Rights (NCHR) representative Fazila Aliani said.

The rising number of deaths in mining accidents shows the inadequate safety arrangements in Balochistan’s coal mines. It is estimated that 80 coal miners die in Balochistan every year, according to the NHCR Balochistan chapter.Coal mine incidents in Balochistan during the recent years have raised valid questions about the standards of safety protocols.

On 5 May 2018, two coal mine accidents left 23 dead while several other were injured. The incident occurred in the Marwar area, 45 km away from Quetta, due to accumulation of methane gas. The mines collapsed, dumping the rubble at the exit point and trapping the workers inside.

The rising number of deaths in mining accidents shows the inadequate safety arrangements in the Balochistan’s coal mines. It is estimated that 80 coal miners die in Balochistan every year, according to the NHCR Balochistan chapter.

Later, another incident occurred in Sur-range area, some 60 kilometres away from Quetta. The accident was due to a mudslide in a mine owned by Pakistan Mineral Development Corporation (PMDC).

There are constant threats of explosions inside coal mines, methane gas poisoning, suffocation, and collapsing of mines, and there is barely a single worker across the five massive commercial coal mines of province, who has not been touched by the accidents that are common here.

A student of Balochistan University of Information Technology, Engineering and Management Sciences in Quetta has built a smart helmet that could save lives of coal miners. The helmet detects the presence of poisonous gases such as carbon monoxide and methane, and a sensor fixed on the helmet activates an alarm if the gas levels increase.

“The invention can surely decrease the number of causalities in coal mines, which results in the deaths of hundreds of labourers every year,” the student inventor Ali Gul said.

He said most accidents occur due to the spread of poisonous gases in coal mines, but often result in massive casualties due to lack of basic safety protocols.

Gul’s helmet is controlled via a wireless sensor network. People from a control room can track the real-time location of the worker easily. They can check the temperature of the mine and the labourer’s oxygen level all the time. It can be monitored through a desktop or mobile application, without much trouble. Gul has created the prototype for his university’s final project. He said he decided to do something about the safety of miners because there were accidents happening in mines, especially in his hometown Sanjawi, every other day.

The prototype of the helmet was tested in couple of mines and passed its initial examination. The young engineer has received a grant of Rs. 40 million from the Higher Education Commission (HEC) Technology Development Fund for the project.