Nothing sums up the dilemma of the Western occupiers of Afghanistan more than an oil painting by Elizabeth Thompson, Lady Butler. It shows a lonely, half-dead Dr. William Bryden of the British Army making his way on a horse to Jalalabad Fort. He was the sole survivor of the 16,500 British soldiers, personnel and their families who had left Kabul in January 1842 for Jalalabad.

During their rule of India, the British were always fearful of the Russian adventurism in India. To safeguard against that fear, the British tried hard to have a compliant and subservient Afghanistan.

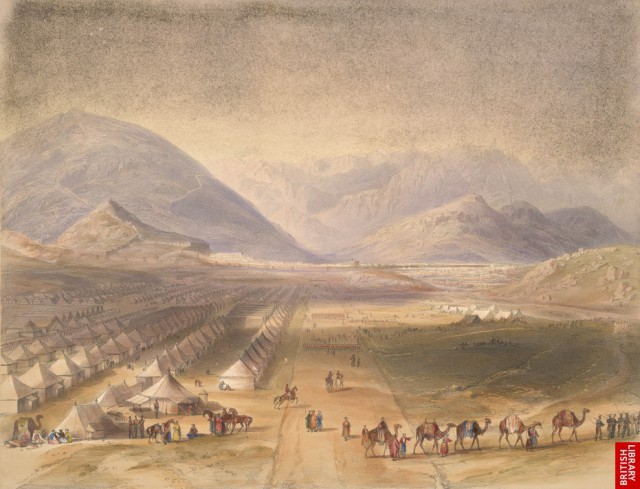

In 1839, British authorities realized that Afghan King Dost Muhammad Khan was secretly receiving envoys of Russian monarch Nicholas I. The British decided to depose Dost Muhammad Khan and replace him with Shah Shujah, a onetime king of Afghanistan, who had been living in exile in India for thirty years. The British East India Company sent an army into Afghanistan in 1839 to restore Shah Shujah to the throne. The new king, however, was detested by most Afghans and soon opposition to the British and the newly installed king started to gather momentum.

After installing Shah Shujah to the throne, the British contingent settled down to a life of leisure. The British ambassador to Kabul, William Hay Macnaghten, lived lavishly in Kabul, hosted grand dinner parties for East India Company officers, arranged cricket games, horse races and hunting parties. They even had amateur actors staging Shakespeare’s plays in Kabul.

The ambassador did not pay attention to the gathering storm and was oblivious to the resentment of the Afghans. He was assassinated and so was the great explorer and diplomat, Alexander Burnes, also lived in Kabul at that time.

Shah Shujah was himself in trouble and thus could not guarantee safety of British forces and personnel. So, the British negotiated with rebels a safe passage from Kabul to Jalalabad that lies 100 miles to the east. In Jalalabad, the British had maintained a strong force.

The ill-fated retreat began on the 6th of January, 1842, And on the seventh day, a half-dead ghost-like figure appeared on horseback at the gate of Jalalabad Fort to tell the story of the massacre. "Remnants of an Army" was painted by Elizabeth Thompson, Lady Butler in 1879 - some 37 years after the incident. It remains an iconic image underlying the futility of invading Afghanistan.

The oft repeated cliché that Afghanistan is the graveyard of empires is largely true. Leave aside countless invaders who fought their way through Afghanistan to reach the plains of India. The empires that came to stay - the British in the middle of the 19th century, the Soviets (1978-89) and the Americans (2001-21) - all had to leave Afghanistan in disgrace.

Since the recent debacle in Kabul, the airways have been rife and newspapers full of pundits expressing their worthless opinions about why America didn’t succeed in Afghanistan. The most glaring group, however, are the retired US generals who had served in Afghanistan. They all tried to absolve themselves of the blame for the debacle to which all of them had contributed. They led the civilian leaders to believe that everything was under control and only if they could have another surge of boots on the ground, the victory would be theirs. It was Vietnam all over again.

Afghanistan is 'ungovernable' in the conventional way. It is a tribal society where allegiance to family, clan and tribe supersede national interests. Add religion to the mix and you have unpredictability. It was the genius of Afghan kings to cobble together several tribes in a governable coalition

The generals were simply looking at their sophisticated weapons and not at the tenacity and dedication of Afghans. The Americans were fighting an open-ended war that was not winnable. Afghans on the other hand fought with only one purpose in mind: to expel foreign forces from their country. The focus of the Taliban was no different than the focus of the Vietnamese 45-years ago.

People often invoke post-WWII Japan and Germany. where the US and the allied powers were able to dictate the shape of the governments in those countries. Afghanistan, however, is not Germany or Japan. Unlike those countries, Afghanistan is a tribal society where tribal traditions and religion play a dominant role in the daily lives of its people. While the Brits, the Soviets and the Americans tried to separate religion from public life, they all failed. It is ironic that the Americans had used the religious card against the Soviets when they supported the Mujahideen.

Afghanistan is 'ungovernable' in the conventional way. It is a tribal society where allegiance to family, clan and tribe supersede national interests. Add religion to the mix and you have unpredictability. It was the genius of Afghan kings to cobble together several tribes in a governable coalition. All Afghan kings were Pashtuns, but in deference to the northern tribes, they chose Dari or Persian and not Pashto as their court language. They balanced tribal interests, religious sensitivities and deep-rooted tribal traditions to govern. Any king who tried to bring in fast social reforms, like Amanullah Khan in 1926, was toppled.

Americans went into Afghanistan with no understanding of the cultural and religious underpinnings of the Afghan people. Despite spending enormous amount of money, they could not win the hearts of the population. The center piece of American policy was emancipation of Afghan women. It succeeded in Kabul but not in the countryside. To export western style liberal democracy to Afghanistan was a non-starter.

American generals had an unheard-of approach to local governance. They would wrest control of an area from the Taliban and install their own Afghans to govern the area. They called it ‘Government in a Box’. No sooner did the Americans leave, that the Taliban would return and toss the US-installed leaders out and start ruling the area.

The same was done on the national level in Afghanistan. American jurists and diplomats wrote the constitution, hand-picked the leaders and when the election result was contentious, they placated the loser by creating a fancy sounding title of chief executive. In the 20 years that the US tried to shape Afghanistan, the writ of US installed national government was limited mostly to the city of Kabul and other provincial cities. In that period, the two Afghan presidents - Hamid Karzai and Ashraf Ghani - were derisively called by many Afghans the glorified mayors of Kabul.

I found the rank-and-file Taliban uninformed about the world at large

After the fall of Kabul, the blame game started in earnest. President Joe Biden is being blamed for the hurried retreat from Afghanistan without proper planning. While the current occupant of the White House should accept blame for a botched-up retreat, the previous administration is as guilty.

It was wrong for the former President Trump to negotiate with the Taliban without the participation of the US-installed Afghan government. Mr. Trump struck up an agreement that only guaranteed no attacks on American and NATO forces. That agreement sold out the Afghan government and betrayed the very reason we went into Afghanistan. The Biden administration had 7 months to plan an orderly withdrawal from Afghanistan, but it did not. We were still counting on the trillion-dollar Afghan army that America funded and trained to put up a resistance. It is ironic that the Soviet-installed government in Afghanistan lasted a full two and a half years after the ignominious withdrawal of the Soviet forces from Afghanistan in 1989.

Are the current Taliban different than the first ones?

In the Western media, questions have been asked if the current reincarnation of the Taliban is any different than their previous version that ruled the country between 1996 to 2002. While I do not have insight into the mindset of the current Taliban, I have some understanding of their modus operandi. In 2000, I visited Afghanistan and met many Taliban leaders. I was there to report for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and Toledo Blade and to collect material for my book on the Taliban (The Taliban and Beyond: A Close Look at the Afghan Nightmare. 2001 BWD Publishers). My visit was facilitated by the late Maulana Sami-ul-Haq, the spiritual godfather of the Taliban, including Mullah Omar the head of the Taliban government. Most of the Taliban leaders were graduates of Sami-ul-Haq’s seminary Darul Uloom Haqqania in Akora Khattak, near Nowshera in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa.

I found the rank-and-file Taliban uninformed about the world at large. They were hopelessly stuck in the context of 7th-century Arabia and believed that their understanding of religion - and only religion - held the key to their future. The only governing model they had in mind was the Muslim community during the Prophet’s (PBUH) time and later during the reign of the first four caliphs. Trying to recreate a distant past, the Taliban created a society where punitive measures took precedent over the ideals of compassion, forgiveness, and welfare.

While they set placed great theological importance on the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), they overlooked his example in their governance of modern Afghan women. It is difficult to imagine how under the rule of this modern group a personality like Khadijah, the businesswoman that the Prophet (PBUH) married, would live her life - given that the Taliban are largely committed to confining a woman within the four walls of her parents’ home. They were more occupied with the physical shape of the society than the philosophical underpinnings of Islamic teachings.

The current Taliban have said that women will have freedom as allowed by the Shariah laws. Those laws, however, are subject to interpretation. Whether the interpretation of ultra-orthodox ISIS or the Wahhabi brand from Saudi Arabia will be their guiding light, or if they will look at neighbouring Pakistan and other Muslim countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia for inspiration is anybody’s guess.