In the end, the Taliban were essentially handed back control of Afghanistan by Washington. The writing was on the wall when, on July 1, American troops vacated the Bagram Air Base that had served as the primary staging ground for the US war in Afghanistan. There was no ceremonial pomp and splendor. Afghan officials discovered the next morning that their American patrons had all but tiptoed out of Bagram in secrecy.

Six weeks later, the Taliban waltzed into Kabul and declared victory. Twenty years after Afghanistan became the first theatre of the so-called ‘war on terror’, with trillions of dollars spent and hundreds of thousands of lives lost, the world stands witness to a quite absurd spectacle that gives new meaning to the adage ‘the more things change, the more they stay the same.’

The avowed objective behind the invasion and occupation of Afghanistan in the wake of the 9/11 attacks was regime change: the Taliban, accused of sheltering 9/11 attackers, would ostensibly be replaced by a ‘popular’ government of the people, for the people, and by the people.

Far from being ousted, the Taliban retained control of parts of the Afghan countryside for most of the past twenty years, the US-backed government in Kabul perpetually embroiled in a struggle to exercise sovereign power over all of the country’s territory. When the final drawdown of US troops was announced at the toe-end of the Trump presidency, reinvigorated Taliban factions must have known that it was a matter of time before they would be back in the saddle. But arguably even they could not have imagined how rapidly the dominoes would fall.

The ‘war on terror’ in Afghanistan was never about establishing a lasting peace, or reining in the militant right-wing. Just like the invasion and occupation of Iraq was never about weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and replacing dictatorship with democracy. George W. Bush’s recent attempts to rebrand himself a peacenik betray the fact that it was his administration, with recently deceased Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney at the helm, that launched the project for a ‘New American Century,’ expanding further what was already a formidable network of US military bases around the world. As Chalmers Johnson incisively noted, “America’s version of the colony is the military base.”

Bush-Cheney-Rumsfeld made Haliburton, Blackwater and other contractors the face of a 21st century ‘public-private’ war-making machine. Trump and now Biden have shifted rhetorical focus away from the ‘war on terror’ and instead upped the ante against China. But imperial desires to control natural resources and assert military might in old stomping grounds remain as pronounced as ever in Washington. In much of west Asia and the Middle East, the fallouts of US militarism continue to be borne by ordinary civilian populations.

Upon taking Kabul, the Taliban declared that the “war is over.” The scenes during and after their takeover, however, suggest that many Afghans are expecting anything but a lasting peace.

Afghanistan’s war ravaged, multi-ethnic society is as volatile as ever. While Ashraf Ghani met with and handed over power to the Taliban in the presidential palace before departing the country, Vice President Amrullah Saleh, of Tajik descent and a pillar of the Northern Alliance that was propelled to power in the immediate aftermath of the American invasion in 2001, refused to surrender. Holed up in Panjshir, he may well close ranks with long-time Taliban opponents like Rashid Dostum and become the focal point of yet another prolonged challenge to the government in Kabul.

From the time of the so-called Great Game that extended through the rule of the British Empire in India, and then before and after the Soviet-backed Saur Revolution in 1978, Pashtuns and non-Pashtuns alike have been instrumentalized by regional and global powers. The deadly strategic games are set to continue.

Pakistan is not the only regional player that is engaged in cynical posturing for power in the post-US withdrawal phase. A high-profile Taliban delegation visited Beijing to meet Chinese officials even before their takeover of Kabul. The latter sought assurances that Afghan territory will not be the staging ground for militancy within China, particularly in the restive Xinjiang province which is home to the beleaguered Uighur ethnic minority. Beijing is presumably satisfied with what it has been promised, for it was one of the first countries to at least provisionally recognize the incoming Taliban regime.

Meanwhile Iran continues to actively engage non-Pashtun players in western Afghanistan, India is scrambling to ensure that its multi-billion dollar investments in the country are protected, and Russia was one of the only countries to keep its embassy open after the Taliban takeover. Needless to say, all are jostling to protect their own narrow strategic interest, irrespective of how much politically correct language about ‘human rights’ prevails in diplomatic circles.

Pakistan is, nevertheless, in a category of its own. Its long term patronage of the Afghan Taliban is amongst the most established facts about the Afghan imbroglio, and there is little reason to believe that Islamabad’s position has undergone a significant makeover.

Recall that neutering secular Pashtun nationalism, including its communist variant, was the motivation for Pakistan, the US, Saudi Arabia and other members of the ‘free world’ to train and arm the original Afghan mujahideen (holy warriors) from the mid 1970s onwards. While the obvious target was the Soviet-backed People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), Pakistan’s military establishment wanted to ensure that its own Pashtun populations were suitably weaned off secular and leftist ideologies.

By all accounts, Pakistani spymasters have welcomed the Taliban’s push for power in post-US Afghanistan. Meanwhile pro-state militants have been allowed to regroup in Pashtun border regions of Pakistan, presumably as an antidote to the anti-war Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM). The question, as ever, is whether the grand strategists will be able to exercise meaningful control over their historic proteges.

Until 2018, Washington hurled accusations in Pakistan’s direction for patronizing certain militant factions in Afghanistan, most notably the so-called Haqqani network. The Obama and Trump administrations froze military aid to exert pressure on their Pakistani counterparts. The former even made haughty claims about promoting democracy in Pakistan and displacing military with civilian aid under the guise of the Kerry-Lugar legislative bill.

Yet since so-called ‘peace talks’ began, Pakistan has been recognized as the primary interlocutor between the Taliban and other Afghan stakeholders. Our military is as powerful as ever and the Pentagon even reportedly asked Islamabad for access to airbases in Pakistani territory to keep a watch on the situation in Afghanistan after the US troop withdrawal.

In the mid-1990s, shortly after first ascent to power, the Taliban enjoyed the good graces of the Clinton administration as the latter sought to build pipelines through Afghanistan to pump oil and gas from the Caspian Sea. Today the Taliban are once again set to do business with the ‘free world.’ There is no principled anti-imperialism motivating the Taliban or their religio-political allies in Pakistan – despite the Jamaa’t-e-Islami and Jamia’t-e-Ulema-Islam celebrating the fall of Kabul as a great victory for the enemies of Empire. Islamist rhetoric certainly produces more foot soldiers for the politics of hate but has never translated into a meaningful challenge to capitalist imperialism.

And it is worth reiterating here that the US military-industrial complex has profited enormously from the war in Afghanistan. As for the ‘embarrassment’ of ‘defeat’ by the Taliban, some observers are already making the claim that the American establishment is quite happy to leave China with the headache of dealing with a reinvigorated Islamist movement in what it has called the ‘Af-Pak’ region.

In the final analysis, however, it is the 40 million people of Afghanistan that will first and foremost have to come to terms with the mess that the Americans are leaving behind. Younger Afghans born after 2001 who believed that American occupation would produce long-lasting peace will have to come to terms with ‘betrayal’ by Washington. When the latest phase of imperialist war began in Afghanistan twenty years ago, at least some of us on the Pakistani left warned that the American right’s militarism would serve only to be a foil to the militant right-wing in our own part of the world.

One can only hope that those who bought into orientialist narratives that the ‘war on terror’ was about ‘saving Afghan women’ and eliminating ‘extremism’ will not discard yet another lesson of history. The progressive cause in Pakistan, Afghanistan and beyond will never be won by surrendering the mantle of anti-imperialism or class struggle to the right-wing. Only when progressive forces in both the western world and the region at large build common cause with a critical mass of Afghans – both Pashtun and non-Pashtun – can there be hope of a lasting peace beyond the machinations of Empire, and regional establishments that, as ever, want only to mint money and secure cynical strategic interests.

The writer teaches at Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad.

Six weeks later, the Taliban waltzed into Kabul and declared victory. Twenty years after Afghanistan became the first theatre of the so-called ‘war on terror’, with trillions of dollars spent and hundreds of thousands of lives lost, the world stands witness to a quite absurd spectacle that gives new meaning to the adage ‘the more things change, the more they stay the same.’

The avowed objective behind the invasion and occupation of Afghanistan in the wake of the 9/11 attacks was regime change: the Taliban, accused of sheltering 9/11 attackers, would ostensibly be replaced by a ‘popular’ government of the people, for the people, and by the people.

Far from being ousted, the Taliban retained control of parts of the Afghan countryside for most of the past twenty years, the US-backed government in Kabul perpetually embroiled in a struggle to exercise sovereign power over all of the country’s territory. When the final drawdown of US troops was announced at the toe-end of the Trump presidency, reinvigorated Taliban factions must have known that it was a matter of time before they would be back in the saddle. But arguably even they could not have imagined how rapidly the dominoes would fall.

The ‘war on terror’ in Afghanistan was never about establishing a lasting peace, or reining in the militant right-wing. Just like the invasion and occupation of Iraq was never about weapons of mass destruction (WMD) and replacing dictatorship with democracy. George W. Bush’s recent attempts to rebrand himself a peacenik betray the fact that it was his administration, with recently deceased Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney at the helm, that launched the project for a ‘New American Century,’ expanding further what was already a formidable network of US military bases around the world. As Chalmers Johnson incisively noted, “America’s version of the colony is the military base.”

Bush-Cheney-Rumsfeld made Haliburton, Blackwater and other contractors the face of a 21st century ‘public-private’ war-making machine. Trump and now Biden have shifted rhetorical focus away from the ‘war on terror’ and instead upped the ante against China. But imperial desires to control natural resources and assert military might in old stomping grounds remain as pronounced as ever in Washington. In much of west Asia and the Middle East, the fallouts of US militarism continue to be borne by ordinary civilian populations.

Upon taking Kabul, the Taliban declared that the “war is over.” The scenes during and after their takeover, however, suggest that many Afghans are expecting anything but a lasting peace.

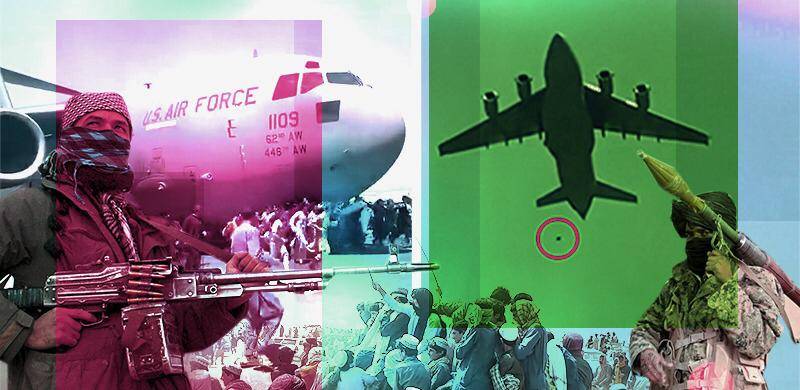

Young men clinging onto planes departing Kabul Airport and then falling to their death symbolized both the trauma of the recent past, and anticipation of what may be coming.

Afghanistan’s war ravaged, multi-ethnic society is as volatile as ever. While Ashraf Ghani met with and handed over power to the Taliban in the presidential palace before departing the country, Vice President Amrullah Saleh, of Tajik descent and a pillar of the Northern Alliance that was propelled to power in the immediate aftermath of the American invasion in 2001, refused to surrender. Holed up in Panjshir, he may well close ranks with long-time Taliban opponents like Rashid Dostum and become the focal point of yet another prolonged challenge to the government in Kabul.

From the time of the so-called Great Game that extended through the rule of the British Empire in India, and then before and after the Soviet-backed Saur Revolution in 1978, Pashtuns and non-Pashtuns alike have been instrumentalized by regional and global powers. The deadly strategic games are set to continue.

Pakistan is not the only regional player that is engaged in cynical posturing for power in the post-US withdrawal phase. A high-profile Taliban delegation visited Beijing to meet Chinese officials even before their takeover of Kabul. The latter sought assurances that Afghan territory will not be the staging ground for militancy within China, particularly in the restive Xinjiang province which is home to the beleaguered Uighur ethnic minority. Beijing is presumably satisfied with what it has been promised, for it was one of the first countries to at least provisionally recognize the incoming Taliban regime.

Meanwhile Iran continues to actively engage non-Pashtun players in western Afghanistan, India is scrambling to ensure that its multi-billion dollar investments in the country are protected, and Russia was one of the only countries to keep its embassy open after the Taliban takeover. Needless to say, all are jostling to protect their own narrow strategic interest, irrespective of how much politically correct language about ‘human rights’ prevails in diplomatic circles.

Pakistan is, nevertheless, in a category of its own. Its long term patronage of the Afghan Taliban is amongst the most established facts about the Afghan imbroglio, and there is little reason to believe that Islamabad’s position has undergone a significant makeover.

Recall that neutering secular Pashtun nationalism, including its communist variant, was the motivation for Pakistan, the US, Saudi Arabia and other members of the ‘free world’ to train and arm the original Afghan mujahideen (holy warriors) from the mid 1970s onwards. While the obvious target was the Soviet-backed People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), Pakistan’s military establishment wanted to ensure that its own Pashtun populations were suitably weaned off secular and leftist ideologies.

By all accounts, Pakistani spymasters have welcomed the Taliban’s push for power in post-US Afghanistan. Meanwhile pro-state militants have been allowed to regroup in Pashtun border regions of Pakistan, presumably as an antidote to the anti-war Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM). The question, as ever, is whether the grand strategists will be able to exercise meaningful control over their historic proteges.

Until 2018, Washington hurled accusations in Pakistan’s direction for patronizing certain militant factions in Afghanistan, most notably the so-called Haqqani network. The Obama and Trump administrations froze military aid to exert pressure on their Pakistani counterparts. The former even made haughty claims about promoting democracy in Pakistan and displacing military with civilian aid under the guise of the Kerry-Lugar legislative bill.

Yet since so-called ‘peace talks’ began, Pakistan has been recognized as the primary interlocutor between the Taliban and other Afghan stakeholders. Our military is as powerful as ever and the Pentagon even reportedly asked Islamabad for access to airbases in Pakistani territory to keep a watch on the situation in Afghanistan after the US troop withdrawal.

In the mid-1990s, shortly after first ascent to power, the Taliban enjoyed the good graces of the Clinton administration as the latter sought to build pipelines through Afghanistan to pump oil and gas from the Caspian Sea. Today the Taliban are once again set to do business with the ‘free world.’ There is no principled anti-imperialism motivating the Taliban or their religio-political allies in Pakistan – despite the Jamaa’t-e-Islami and Jamia’t-e-Ulema-Islam celebrating the fall of Kabul as a great victory for the enemies of Empire. Islamist rhetoric certainly produces more foot soldiers for the politics of hate but has never translated into a meaningful challenge to capitalist imperialism.

And it is worth reiterating here that the US military-industrial complex has profited enormously from the war in Afghanistan. As for the ‘embarrassment’ of ‘defeat’ by the Taliban, some observers are already making the claim that the American establishment is quite happy to leave China with the headache of dealing with a reinvigorated Islamist movement in what it has called the ‘Af-Pak’ region.

In the final analysis, however, it is the 40 million people of Afghanistan that will first and foremost have to come to terms with the mess that the Americans are leaving behind. Younger Afghans born after 2001 who believed that American occupation would produce long-lasting peace will have to come to terms with ‘betrayal’ by Washington. When the latest phase of imperialist war began in Afghanistan twenty years ago, at least some of us on the Pakistani left warned that the American right’s militarism would serve only to be a foil to the militant right-wing in our own part of the world.

One can only hope that those who bought into orientialist narratives that the ‘war on terror’ was about ‘saving Afghan women’ and eliminating ‘extremism’ will not discard yet another lesson of history. The progressive cause in Pakistan, Afghanistan and beyond will never be won by surrendering the mantle of anti-imperialism or class struggle to the right-wing. Only when progressive forces in both the western world and the region at large build common cause with a critical mass of Afghans – both Pashtun and non-Pashtun – can there be hope of a lasting peace beyond the machinations of Empire, and regional establishments that, as ever, want only to mint money and secure cynical strategic interests.

The writer teaches at Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad.