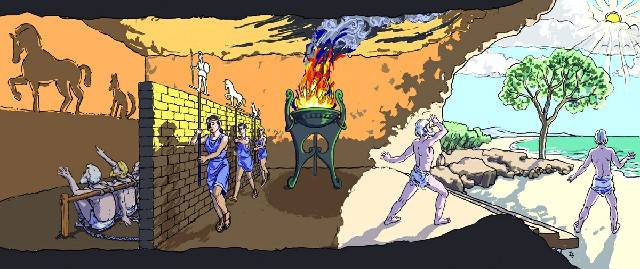

It has been discerned for centuries that the bond between philosophy and literature is unshakable and unflagging. Each subject matter aggrandizes and accredits the other, providing compelling paradigms and enthralling exemplifications. However, despite their dynamic relationship, what is more intriguing is how Western philosophy has been employed to advocate an avant-garde theme like feminism in Arab literature. Western philosophy and Arab literature, in defiance of their countless differences, appear as two sides of the same coin, which are utilized time and again to transform stereotypes and revamp obsolete norms. Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and the line being among the most prominent metaphors in Western philosophy, these serve the sole purpose of elucidating the significance of education and knowledge on the human soul. It all highlights the underlying reality that knowledge gives humans an unrivaled status among God’s other manifestations and places them on different strata in the same society based on their mental capacity and degree of awareness. We come across female figures with idiosyncratic roles who commence an arduous journey to find the truth – an amalgamation of philosophy and literature. Despite the barriers and hindrances created by a prejudiced society, these women are among the handful of those who determine the World’s bona fide reality.

Many noteworthy authors ranging from Mahfouz to Al-Shaykh depict this dilemma of mental dissimilitude and inability to grasp the actual Forms of the Good in their peculiar novels. In light of the Allegory of the Cave and line, these well-known Arab authors have presented distinct female characters who defy cultural stereotypes in their attempt to attain freedom and their due rights as equal members of society. These women represented in different novels belong to contrasting cultural gateways and various positions from the economic spectrum – and they set about on a journey of discovering reality, like the prisoner who sets foot outside the cave’s obscurity to find about the actuality.

The agency of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and line is brilliantly used by Tayeb Salih, an esteemed Arabic author, to crush the stereotypical roles of females in his timeless novel Season of Migration to the North. Salih puts forward the character of Hosna, which represents the journey of the prisoner who escapes the tortuousness of the Cave. The novel, centered on the estrangement and alienation that one faces due to the never-ending tussle between traditionalism and Westernization, is based on Wad Hamid’s village, which lies along the river Nile coast. Like the prisoners who co-construct the World based on their opinions, the villagers are blinded by their brutal traditions and practices like female circumcision. However, amidst this contortion of truth, Hosna is the only prisoner who escapes and witnesses an alteration in her view of the World. Being the wife and later widow of an educated man like Mustafa Saeed, our Hosna becomes aware of women’s fundamental rights and the necessity to raise their voice against injustice. When forced to marry Wad Rayyes, a man much older than herself, Hosna shows immense resistance, trying to awaken the ignorant villagers’ consciousness against barbarism, reinforcing her synonymity as an enlightened prisoner. She attempts to put an end to the oppressive norms that subject women to misogyny and violence. Thus, she is seen defying the stereotype of a village girl who remains enslaved by the customs, traditions, and self-important male household members. Her acts of courage against toxic masculinity, though, are harshly condemned by the villagers – prisoners of the Cave for whom the truth is merely an interpretive existence and a series of shadows cast by British colonialism. Hosna’s response towards chauvinism emphasizes the importance of consent in any relationship, eradicating the stereotype that women are impotent and incompetent to guard their dignity and protect themselves from sexual oppression and essential concepts like marital rape. By putting forward the notion of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and line to establish the character of Hosna as a diametric to stereotypical female, Tayib Saih not only demonstrates that the attainment of the truth might not always lead to prosperity like becoming a philosopher-king and uplifting others as per the theory but also projects a monumental degree of coherence between the two distinct subject matters.

Another female character built through Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and line, reflecting the parallelism between Western philosophy and Arab literature, is Zahra in Hanan Al-Shaykh’s exalted novel The Story of Zahra. Here, the story of Zahra is about the subversive sexual and social identities confined within patriarchal society’s parameters. The novel revolves around Zahra’s journey, who suffers greatly at a misogynistic society’s hands because of the conflation of her body and identity with the nation. As the escaped prisoner in the cave, Zahra is the only one among the nescient lot to realize the political violence and oppression against the nation’s sexual “Others,” specifically women. Analogous to the people stuck in the Cave, the people around Zahra remain hooked to their traditional ideologies, for instance, “Nation as Woman” and “Woman as Nation.” These people’s unwavering belief in women’s purity and authenticity as the symbol of national honour and pride is immensely hypocritical for a society where women are subjugated and serve as muted vestiges to satisfy the bruised ego of men who suffered losses on the battlefield. Like the cave, Zahra’s surroundings also represent women’s privatization from political, social, and economic power, isolating them from the decision-making process like prisoners from the punishment to be prescribed. This involves a society circumscribing women’s role and confining their status by epitomizing it in “pure” motherhood or womanhood. The formulation of chauvinistic policies and agendas is so brilliant in such societies that, like the unenlightened prisoners of the Cave, women mistake sexism and discrimination for “respect” and “power.” However, Zahra, akin to the escaped prisoner, learns about the reality of the whole misogynistic structure of the society created in such a geometric fashion that if one part is damaged, the entire system crumbles down and decides to overthrow it. Like the escaped prisoner who transitions from the visible realm to the intelligible realm, Zahra also escapes the private realm, entering the political realm that is considered incompatible for women who are supposed to be homemakers, not policymakers. In her attempt to engage in and change the political arena, Zahra gets sexually involved with a sniper to distract him from his murderous activities. These events signify how Al-Shaykh uses Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and line to break the stereotypical female roles in Arabic literature. Zahra embodies the role of the least respected woman of the society, a “whore.” In her struggle to be politically active in the war and with no other options available, she begins a sexual escapade with the sniper – thwarting the preconceived notions of a respectable woman not only for her parents, brother and society and even the reader correspondingly. Even though one might not be a proponent of Zahra’s audacious endeavours, the finesse with which her character breaks stereotypical roles in Arabic literature employing Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and line is not only notable but efficacious in depicting the two subjects as undeniably similar.

Many authors have remarkably employed Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and line in Arabic literature to break stereotypical female roles – in the process, shedding light on the fascinating and incredible blend of philosophy and literature. Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and line that demonstrates the Form of the Good as the prime source of intelligibility and truth is not only a masterpiece that has survived the course of philosophy but a comprehensive notion that serves as a bridge between two peculiar subjects of thought, making it imperishable and the two subjects as two sides of the same coin.

Many noteworthy authors ranging from Mahfouz to Al-Shaykh depict this dilemma of mental dissimilitude and inability to grasp the actual Forms of the Good in their peculiar novels. In light of the Allegory of the Cave and line, these well-known Arab authors have presented distinct female characters who defy cultural stereotypes in their attempt to attain freedom and their due rights as equal members of society. These women represented in different novels belong to contrasting cultural gateways and various positions from the economic spectrum – and they set about on a journey of discovering reality, like the prisoner who sets foot outside the cave’s obscurity to find about the actuality.

Salih puts forward the character of Hosna, which represents the journey of the prisoner who escapes the tortuousness of the Cave

The agency of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and line is brilliantly used by Tayeb Salih, an esteemed Arabic author, to crush the stereotypical roles of females in his timeless novel Season of Migration to the North. Salih puts forward the character of Hosna, which represents the journey of the prisoner who escapes the tortuousness of the Cave. The novel, centered on the estrangement and alienation that one faces due to the never-ending tussle between traditionalism and Westernization, is based on Wad Hamid’s village, which lies along the river Nile coast. Like the prisoners who co-construct the World based on their opinions, the villagers are blinded by their brutal traditions and practices like female circumcision. However, amidst this contortion of truth, Hosna is the only prisoner who escapes and witnesses an alteration in her view of the World. Being the wife and later widow of an educated man like Mustafa Saeed, our Hosna becomes aware of women’s fundamental rights and the necessity to raise their voice against injustice. When forced to marry Wad Rayyes, a man much older than herself, Hosna shows immense resistance, trying to awaken the ignorant villagers’ consciousness against barbarism, reinforcing her synonymity as an enlightened prisoner. She attempts to put an end to the oppressive norms that subject women to misogyny and violence. Thus, she is seen defying the stereotype of a village girl who remains enslaved by the customs, traditions, and self-important male household members. Her acts of courage against toxic masculinity, though, are harshly condemned by the villagers – prisoners of the Cave for whom the truth is merely an interpretive existence and a series of shadows cast by British colonialism. Hosna’s response towards chauvinism emphasizes the importance of consent in any relationship, eradicating the stereotype that women are impotent and incompetent to guard their dignity and protect themselves from sexual oppression and essential concepts like marital rape. By putting forward the notion of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and line to establish the character of Hosna as a diametric to stereotypical female, Tayib Saih not only demonstrates that the attainment of the truth might not always lead to prosperity like becoming a philosopher-king and uplifting others as per the theory but also projects a monumental degree of coherence between the two distinct subject matters.

Another female character built through Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and line, reflecting the parallelism between Western philosophy and Arab literature, is Zahra in Hanan Al-Shaykh’s exalted novel The Story of Zahra. Here, the story of Zahra is about the subversive sexual and social identities confined within patriarchal society’s parameters. The novel revolves around Zahra’s journey, who suffers greatly at a misogynistic society’s hands because of the conflation of her body and identity with the nation. As the escaped prisoner in the cave, Zahra is the only one among the nescient lot to realize the political violence and oppression against the nation’s sexual “Others,” specifically women. Analogous to the people stuck in the Cave, the people around Zahra remain hooked to their traditional ideologies, for instance, “Nation as Woman” and “Woman as Nation.” These people’s unwavering belief in women’s purity and authenticity as the symbol of national honour and pride is immensely hypocritical for a society where women are subjugated and serve as muted vestiges to satisfy the bruised ego of men who suffered losses on the battlefield. Like the cave, Zahra’s surroundings also represent women’s privatization from political, social, and economic power, isolating them from the decision-making process like prisoners from the punishment to be prescribed. This involves a society circumscribing women’s role and confining their status by epitomizing it in “pure” motherhood or womanhood. The formulation of chauvinistic policies and agendas is so brilliant in such societies that, like the unenlightened prisoners of the Cave, women mistake sexism and discrimination for “respect” and “power.” However, Zahra, akin to the escaped prisoner, learns about the reality of the whole misogynistic structure of the society created in such a geometric fashion that if one part is damaged, the entire system crumbles down and decides to overthrow it. Like the escaped prisoner who transitions from the visible realm to the intelligible realm, Zahra also escapes the private realm, entering the political realm that is considered incompatible for women who are supposed to be homemakers, not policymakers. In her attempt to engage in and change the political arena, Zahra gets sexually involved with a sniper to distract him from his murderous activities. These events signify how Al-Shaykh uses Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and line to break the stereotypical female roles in Arabic literature. Zahra embodies the role of the least respected woman of the society, a “whore.” In her struggle to be politically active in the war and with no other options available, she begins a sexual escapade with the sniper – thwarting the preconceived notions of a respectable woman not only for her parents, brother and society and even the reader correspondingly. Even though one might not be a proponent of Zahra’s audacious endeavours, the finesse with which her character breaks stereotypical roles in Arabic literature employing Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and line is not only notable but efficacious in depicting the two subjects as undeniably similar.

Many authors have remarkably employed Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and line in Arabic literature to break stereotypical female roles – in the process, shedding light on the fascinating and incredible blend of philosophy and literature. Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and line that demonstrates the Form of the Good as the prime source of intelligibility and truth is not only a masterpiece that has survived the course of philosophy but a comprehensive notion that serves as a bridge between two peculiar subjects of thought, making it imperishable and the two subjects as two sides of the same coin.