The situation in Afghanistan continues to evolve since I last wrote about Pakistan’s counterterrorism options two weeks ago. Friend and fellow scribe Mosharraf Zaidi has penned two more articles in the meantime, as have some others. Meanwhile, the political opposition, as also Pashtun nationalist politicians, groups and analysts, continue to criticise the government’s Afghanistan policy.

Let me first begin with the government’s handling of the situation. In simple terms, the government’s policy, containing multiple strategies, is comprehensive and sound. This does not mean that all the strategies will have desired outcomes. It means that since Afghanistan is a wicked problem, the government’s policy is as good as it can get. Of course, one can cherry-pick details, but that is at best a partisan exercise and at worst agenda-driven trolling.

So, what is the government doing?

One, it is closely monitoring the situation in Afghanistan where multiple actors are contesting for political space. The most obvious protagonists are the government of President Ashraf Ghani and the Taliban insurgent movement. A third actor is Ghani’s political opposition.

This third force, which includes multiple political parties and groups, is politically opposed to Ghani but also not completely aligned or allied with the Taliban. Reports suggest that the Taliban leadership is in contact with most of these actors to work out a deal on a future set-up sans Ghani and his coterie. Other actors in this contested space are Daesh (a violent spoiler), terrorist groups attacking Pakistan, Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, East Turkestan Islamic Movement, Al-Qaeda and sundry freelancers.

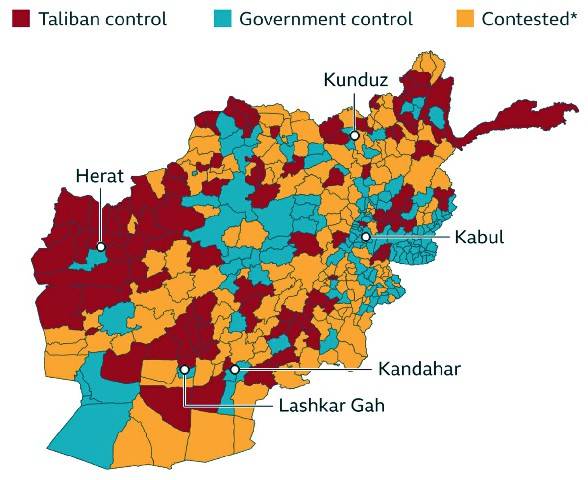

Two, it is now an uncontested fact that the Taliban have taken more territory in Afghanistan in the last two months than at any time since they were ousted from power in 2001. They control multiple border crossings and latest reports say they have begun collecting taxes at the crossings they control. But, and this is important to put things in perspective, a survey conducted from November 2020 to February 2021 by Pajhwok Afghan News showed that the control of the country was somewhat evenly split with the Taliban controlling 337,000 sq km of the area and the government 297,000 sq km. About 18,000 sq km was not controlled by either.

The survey is important because it shows that the current Taliban gains are not the equivalent of a sudden cloudburst. Instead, Taliban have built on previous gains made before the decision by US President Joe Biden’s announcement to withdraw remaining US troops unconditionally. Furthermore, the survey was conducted and published by Afghan media outlets that have a genuine vested interest in the continuation of the current Afghanistan constitutional set-up, which would be upset by a Taliban takeover.

Three, while the Ghani government remains the legitimate representative of Afghanistan at various international fora, all regional and extra-regional powers have reached out to the Taliban, starting with the United States itself inking a deal with the Islamic Emirate. Before that Iran, Russia and China were already in contact with Taliban representatives. I mention these countries because most analyses in Pakistan, for various reasons, refer to the nexus between Pakistan and the Taliban and tend to portray the Taliban as Pakistan’s proxies which Pakistan controls. Nothing could be further from the truth. The Taliban are a fiercely independent movement and while some pressure can be exerted on them, to think that Pakistan can choreograph their actions like Iran can control its proxies in Iraq or Lebanon is to be either naive or malicious.

In this month alone, Taliban delegations have been to Iran, Russia and last Wednesday to Tianjin in northern China where Mullah Ghani Baradar met with China’s state councillor and foreign minister Wang Yi. On July 13, UK’s defence secretary Ben Wallace told Daily Telegraph that the UK will work with the Taliban should they enter the government in Kabul, especially if they adhere to certain international norms. India has tried at a delegation level and twice at the level of their foreign minister to meet with the Taliban, but has been rebuffed.

Four, there is a violent contest for supremacy between Taliban fighters and Afghan National Defence and Security Forces. While in some places Afghan special forces (which roughly number about 50,000 personnel) continue to give a fight, other elements of ANDSF have generally been folding before the Taliban. Afghan soldiers have been crossing over into Iran, Tajikistan and most recently Pakistan. Their morale is low and after the Dawlat Abad incident where an Afghan commando platoon was left to its own devices and got killed, not many are prepared to fight. Also, it is only in and around provincial capitals that the US and Afghan Air Force is providing close air support to government troops. Without that support, the ANDSF troops don’t stand much chance before Taliban fighters who have used a mix of talks/deals with the local populations and the threat of use of force to gain ground.

Five, Pakistan is not the only actor in the region. It also has to contend with Indian activities and the nexus between India and some elements of the current Afghan government. Further, there are other regional and extra-regional actors that are actively involved in the goings-on in that country and their objectives and interest may or may not sync with Pakistan’s.

Six, most important from Pakistan’s perspective, Pakistani terrorist groups (TTP and its affiliates, as also BRAS, the four-group alliance of Baloch terrorists) are situated in many contested and often ungoverned spaces in Afghanistan. They constitute an immediate and also medium- to long-term threat.

This, then, is the lay of the land in which Pakistan has to formulate its policy and the various strategies it subsumes. What are the salient points of that policy?

One, Pakistan is committed to getting the three major parties, Ghani government, Taliban and Ghani’s political opposition (generally referred to as other stakeholders) to come to some kind of agreement that can lead to a reduction in violence leading to a permanent ceasefire and an agreed provisional set-up that can work out a future constitutional arrangement for Afghanistan. However, and this is important to note, Pakistan’s role is that of a facilitator only. Ultimately, as is acknowledged by all interested state actors, including the US, that deal has to be worked out by the Afghans.

Two, notwithstanding deliberate provocations by Ghani, his first vice president Amrullah Saleh and his national security advisor Hamdullah Mohib, Pakistan has patiently continued to work with the Kabul government, even as it has consistently nudged the Taliban leadership in the direction of talks. It is important to note here that those who want Pakistan to coerce the Taliban are either ignoring the ground situation or trotting out a nationalist, partisan line. Let’s assume that Pakistan decides to coerce the Taliban in favour of a government in Kabul that continues to voice its irredentism with reference to the border, what happens if the Taliban refuse to budge? There would be two choices: either Pakistan will have to retreat from that policy and lose all remaining leverage, or Pakistan will have to double down. The first is bad enough; the second is worse because it would mean Pakistan using force against one set of contestants to save another set of Afghans. No policymaker with any sense of politico-military strategy would do that. Hence the requirement for keeping a patient balance.

Three, while working towards a settlement, Pakistan is also actively involved diplomatically to get a regional consensus on joint actions, especially with China but also with Russia and the Central Asian states. If anyone thinks that Wang and Baradar met out of the blue, (s)he should go back to reading Mills & Boon.

The Taliban have also indicated, as evident from Taliban spokesperson Suhail Shaheen’s interview to Associated Press, that Taliban consider the monopolisation of power a “failed formula”, which did not work in the past and is unlikely to going forward. But he was uncompromising on Ghani’s right to rule and said the Taliban will lay down their weapons when a negotiated government acceptable to all sides in the conflict is installed in Kabul and Ghani’s government is gone.

That, as I have noted before, is the central and sticking point. Even so, there’s much in what Shaheen said that indicates there might still be space for a settlement. Taliban leadership also realises, as per statements, that returning to power requires international legitimacy. It is that space Pakistan wishes to exploit in working towards a deal.

Four, Pakistan is simultaneously preparing for a failure of diplomatic efforts and, consequent to that, heightened violence in Afghanistan. That involves two major spillovers: refugee inflow and cross-border terrorism. This is where I go back to my original formulation: develop offensive CT capabilities — i.e., pick up intelligence early and act on it. I have already written about the issue with reference to Zaidi’s sovereignty point (more can be said on that) so I won’t repeat it, but it is interesting to note something I had referred to in my previous article:

“Are [info-tech/cyber offensives] different from covert, physical attacks, despite their subversive potential? In that, while we must develop trans-border capabilities to counter hostile actions in the digital domain, we must approach sovereignty as a notion carved in stone when it comes to covert actions by state and non-state actors, even when a state…has no real government and legitimacy itself is being contested…. These are important questions and given the emerging technologies will come into sharper salience in the coming years.”

Interestingly, the National Cyber Security Policy 2021 approved by the cabinet on Tuesday, says a cyberattack on any institution of Pakistan will be considered an act of aggression against national sovereignty and all necessary and retaliatory steps would be taken. What action(s) would that actually entail is a separate debate but gives us much to think about with reference to developing offensive capabilities to counter a broad spectrum of threats.

In short, given the interactive complexity of the situation and the involvement of multiple actors within and outside Afghanistan, the government has to contend with multiple variables. It has so far managed to balance things. That’s as good as it can get at this stage.

The writer is a former News Editor of The Friday Times. He tweets @ejazhaider

Let me first begin with the government’s handling of the situation. In simple terms, the government’s policy, containing multiple strategies, is comprehensive and sound. This does not mean that all the strategies will have desired outcomes. It means that since Afghanistan is a wicked problem, the government’s policy is as good as it can get. Of course, one can cherry-pick details, but that is at best a partisan exercise and at worst agenda-driven trolling.

So, what is the government doing?

One, it is closely monitoring the situation in Afghanistan where multiple actors are contesting for political space. The most obvious protagonists are the government of President Ashraf Ghani and the Taliban insurgent movement. A third actor is Ghani’s political opposition.

This third force, which includes multiple political parties and groups, is politically opposed to Ghani but also not completely aligned or allied with the Taliban. Reports suggest that the Taliban leadership is in contact with most of these actors to work out a deal on a future set-up sans Ghani and his coterie. Other actors in this contested space are Daesh (a violent spoiler), terrorist groups attacking Pakistan, Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, East Turkestan Islamic Movement, Al-Qaeda and sundry freelancers.

Two, it is now an uncontested fact that the Taliban have taken more territory in Afghanistan in the last two months than at any time since they were ousted from power in 2001. They control multiple border crossings and latest reports say they have begun collecting taxes at the crossings they control. But, and this is important to put things in perspective, a survey conducted from November 2020 to February 2021 by Pajhwok Afghan News showed that the control of the country was somewhat evenly split with the Taliban controlling 337,000 sq km of the area and the government 297,000 sq km. About 18,000 sq km was not controlled by either.

The survey is important because it shows that the current Taliban gains are not the equivalent of a sudden cloudburst. Instead, Taliban have built on previous gains made before the decision by US President Joe Biden’s announcement to withdraw remaining US troops unconditionally. Furthermore, the survey was conducted and published by Afghan media outlets that have a genuine vested interest in the continuation of the current Afghanistan constitutional set-up, which would be upset by a Taliban takeover.

Three, while the Ghani government remains the legitimate representative of Afghanistan at various international fora, all regional and extra-regional powers have reached out to the Taliban, starting with the United States itself inking a deal with the Islamic Emirate. Before that Iran, Russia and China were already in contact with Taliban representatives. I mention these countries because most analyses in Pakistan, for various reasons, refer to the nexus between Pakistan and the Taliban and tend to portray the Taliban as Pakistan’s proxies which Pakistan controls. Nothing could be further from the truth. The Taliban are a fiercely independent movement and while some pressure can be exerted on them, to think that Pakistan can choreograph their actions like Iran can control its proxies in Iraq or Lebanon is to be either naive or malicious.

In this month alone, Taliban delegations have been to Iran, Russia and last Wednesday to Tianjin in northern China where Mullah Ghani Baradar met with China’s state councillor and foreign minister Wang Yi. On July 13, UK’s defence secretary Ben Wallace told Daily Telegraph that the UK will work with the Taliban should they enter the government in Kabul, especially if they adhere to certain international norms. India has tried at a delegation level and twice at the level of their foreign minister to meet with the Taliban, but has been rebuffed.

Four, there is a violent contest for supremacy between Taliban fighters and Afghan National Defence and Security Forces. While in some places Afghan special forces (which roughly number about 50,000 personnel) continue to give a fight, other elements of ANDSF have generally been folding before the Taliban. Afghan soldiers have been crossing over into Iran, Tajikistan and most recently Pakistan. Their morale is low and after the Dawlat Abad incident where an Afghan commando platoon was left to its own devices and got killed, not many are prepared to fight. Also, it is only in and around provincial capitals that the US and Afghan Air Force is providing close air support to government troops. Without that support, the ANDSF troops don’t stand much chance before Taliban fighters who have used a mix of talks/deals with the local populations and the threat of use of force to gain ground.

Five, Pakistan is not the only actor in the region. It also has to contend with Indian activities and the nexus between India and some elements of the current Afghan government. Further, there are other regional and extra-regional actors that are actively involved in the goings-on in that country and their objectives and interest may or may not sync with Pakistan’s.

Six, most important from Pakistan’s perspective, Pakistani terrorist groups (TTP and its affiliates, as also BRAS, the four-group alliance of Baloch terrorists) are situated in many contested and often ungoverned spaces in Afghanistan. They constitute an immediate and also medium- to long-term threat.

This, then, is the lay of the land in which Pakistan has to formulate its policy and the various strategies it subsumes. What are the salient points of that policy?

One, Pakistan is committed to getting the three major parties, Ghani government, Taliban and Ghani’s political opposition (generally referred to as other stakeholders) to come to some kind of agreement that can lead to a reduction in violence leading to a permanent ceasefire and an agreed provisional set-up that can work out a future constitutional arrangement for Afghanistan. However, and this is important to note, Pakistan’s role is that of a facilitator only. Ultimately, as is acknowledged by all interested state actors, including the US, that deal has to be worked out by the Afghans.

Two, notwithstanding deliberate provocations by Ghani, his first vice president Amrullah Saleh and his national security advisor Hamdullah Mohib, Pakistan has patiently continued to work with the Kabul government, even as it has consistently nudged the Taliban leadership in the direction of talks. It is important to note here that those who want Pakistan to coerce the Taliban are either ignoring the ground situation or trotting out a nationalist, partisan line. Let’s assume that Pakistan decides to coerce the Taliban in favour of a government in Kabul that continues to voice its irredentism with reference to the border, what happens if the Taliban refuse to budge? There would be two choices: either Pakistan will have to retreat from that policy and lose all remaining leverage, or Pakistan will have to double down. The first is bad enough; the second is worse because it would mean Pakistan using force against one set of contestants to save another set of Afghans. No policymaker with any sense of politico-military strategy would do that. Hence the requirement for keeping a patient balance.

Three, while working towards a settlement, Pakistan is also actively involved diplomatically to get a regional consensus on joint actions, especially with China but also with Russia and the Central Asian states. If anyone thinks that Wang and Baradar met out of the blue, (s)he should go back to reading Mills & Boon.

The Taliban have also indicated, as evident from Taliban spokesperson Suhail Shaheen’s interview to Associated Press, that Taliban consider the monopolisation of power a “failed formula”, which did not work in the past and is unlikely to going forward. But he was uncompromising on Ghani’s right to rule and said the Taliban will lay down their weapons when a negotiated government acceptable to all sides in the conflict is installed in Kabul and Ghani’s government is gone.

That, as I have noted before, is the central and sticking point. Even so, there’s much in what Shaheen said that indicates there might still be space for a settlement. Taliban leadership also realises, as per statements, that returning to power requires international legitimacy. It is that space Pakistan wishes to exploit in working towards a deal.

Four, Pakistan is simultaneously preparing for a failure of diplomatic efforts and, consequent to that, heightened violence in Afghanistan. That involves two major spillovers: refugee inflow and cross-border terrorism. This is where I go back to my original formulation: develop offensive CT capabilities — i.e., pick up intelligence early and act on it. I have already written about the issue with reference to Zaidi’s sovereignty point (more can be said on that) so I won’t repeat it, but it is interesting to note something I had referred to in my previous article:

“Are [info-tech/cyber offensives] different from covert, physical attacks, despite their subversive potential? In that, while we must develop trans-border capabilities to counter hostile actions in the digital domain, we must approach sovereignty as a notion carved in stone when it comes to covert actions by state and non-state actors, even when a state…has no real government and legitimacy itself is being contested…. These are important questions and given the emerging technologies will come into sharper salience in the coming years.”

Interestingly, the National Cyber Security Policy 2021 approved by the cabinet on Tuesday, says a cyberattack on any institution of Pakistan will be considered an act of aggression against national sovereignty and all necessary and retaliatory steps would be taken. What action(s) would that actually entail is a separate debate but gives us much to think about with reference to developing offensive capabilities to counter a broad spectrum of threats.

In short, given the interactive complexity of the situation and the involvement of multiple actors within and outside Afghanistan, the government has to contend with multiple variables. It has so far managed to balance things. That’s as good as it can get at this stage.

The writer is a former News Editor of The Friday Times. He tweets @ejazhaider