The Doha dialogue mediated by Pakistan had to orchestrate a broad-based and sustainable peace process in Afghanistan. Peace in Afghanistan has been elusive and there have been many reservations around it – not least of which was the lack of legitimacy of the Taliban faction. There is also the question of whether they are interested in dropping arms and making a transition to peace. The Taliban have, it would be proper to say, broken up into many factions since 9/11. Some of them are more hostile in their hatred of the Americans while others seem to display a more flexible posture in their dealings with the Americans and what they see as an American representative in their country; the Afghan government. The situation is peculiar and the peculiarity of it deepens if one involves the Pakistan factor into it. The Americans have continued to lose their trust in Pakistan – which has amongst other conclusions, led them to not withdraw their forces completely from the wartorn country even after several dates and promises by the Obama administration and later by Trump and the incumbent, Joe Biden.

Interestingly, while Americans see Pakistan as part of the problem and a partner it cannot trust with Afghanistan after its exit anymore, the Afghans see Pakistan not as part of the problem but the problem itself. While Pakistan has supported an American withdrawal from Afghanistan, experts in Pakistan have feared a sudden American exit could intensify the war in Afghanistan and spill it over to Pakistan. Now Pakistan, as its premier has reiterated in a recent interview, blames the losses in the war to the approach followed by the Americans, which has favoured war over dialogue. The Pakistani PM thinks that if the Americans pursued rapprochement in the region, it wouldn’t have left the region unstable and Afghanistan more hostile, aggressive and divided than it was in 2001 when the American forces entered the region.

Experts have analyzed the region, the Afghan war and the American adventurism with a defense strategy and foreign policy lens. The Americans fought the war for two decades but while minor skirmishes and limited warfare continued in some parts of Afghanistan, the last decade in particular did not involve much fighting. The American presence in the region was not as much to decimate the Taliban as much as it was to contain them while it committed to rebuild the wartorn country. The Americans committed to bringing back peace and rebuilding broken institutions, which one would imagine did not take place. Political stability did not return and while analysts look toward political decisions and mistakes as factors leading to instability, the causes are more economic than political.

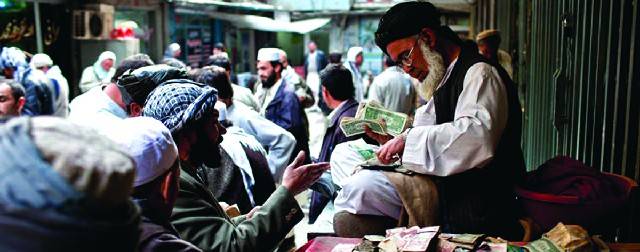

Rebuilding Afghanistan meant creating economic institutions, expanding resources and providing vulnerable groups with sustainable sources of employment and income generation. The Afghan economy has been little reviewed and analyzed because people have not focused on how the economy has behaved under the US and what implications has the economic exclusion of certain groups had on the developing security situation in the region.

GDP growth suffered during Covid but the economic losses borne by Afghanistan are not magnified when looked in comparison with losses suffered by the entire south Asian region. Pakistan has done better to allay the economic fears of Covid compared to the regional average while India has suffered badly at the hands of the deadly virus. Afghanistan, under the American policy influence, has done as well as the region did in 2020; its GDP shrunk by around 1.9%. It had been growing on an average of 2.9% for the five years prior to the onslaught of Covid, a rate that disputes the American claims of investing in economic growth and rebuilding of institutions in the country. Many parts of Afghanistan that are directly controlled by the Taliban may not contribute to the national economy and would instead be diluting the economic gains made by the Americans and the Afghan government in areas that are administratively managed by them. However, the fact that peace has not returned does not completely prove the claim that the Americans fell short of their goals in Afghanistan. Instead, what bears greater reference to American performance in the region is the shaky and failing economy of Afghanistan.

In the first five years of American presence in Afghanistan; that is between 2003 and 2007, GDP grew by 8% on average with 2005 and 2007 as outliers when GDP grew abnormally, 11% and 13%, respectively. The Afghan population was nearly 21 million in 2001, which had nearly doubled to 39 million in 2019. With a population of around 20-25 million in the first five years of American presence in Afghanistan, GDP per capita growth had averaged 4.3%. GDP per capita, in US dollar terms was, around USD 180 in 2002 which increased significantly to USD 508 in 2020. The increase is substantial and while it is indicative of growth and welfare that the American policy and overseas development assistance may have generated in Afghanistan. However, if one looks at the gains that had been achieved at the close of Obama’s first term in office when the policy change to adopt austerity measures in the US and to transition towards an American exit from Afghanistan was made, GDP per capita had maximized to USD 641. With a population that is still under 40 million, the Afghan GDP per capital speaks volumes about how much and how well the Americans have done to resuscitate the afghan economy and bring vulnerable groups into the economic fold. Urban population (as a proportion of total population) has been literally stagnant. From 23% in 2002 to nearly 26% today, the proportion of urban population reflects the lack of city development and growth that has taken place. Much of that can be attributed to Taliban presence in many rural towns however, suburbs of cities administratively controlled by the Afghan government have also not attained urban characteristics at the pace at which one could have imagined that the Americans would have been able to construct urban infrastructure.

The economy has moved with changes in the foreign direct investment and overseas development assistance which implies that indigenous capacity in the economy to generate growth has not been created. Growth has only emerged at times when foreign assistance was available and it disappeared at times when the direct economic assistance of the Americans was not readily available. Health and education statistics also tell a story about the American economic performance. In some of my articles on this page in the future, I would engage with the Afghan development statistics, most particularly its social indicators on health, education and poverty. The effort would will be aimed at building a narrative about the Afghan economy, which is largely absent from the literature.

The writer is an economist based in Islamabad. He tweets @AsadAijaz

Interestingly, while Americans see Pakistan as part of the problem and a partner it cannot trust with Afghanistan after its exit anymore, the Afghans see Pakistan not as part of the problem but the problem itself. While Pakistan has supported an American withdrawal from Afghanistan, experts in Pakistan have feared a sudden American exit could intensify the war in Afghanistan and spill it over to Pakistan. Now Pakistan, as its premier has reiterated in a recent interview, blames the losses in the war to the approach followed by the Americans, which has favoured war over dialogue. The Pakistani PM thinks that if the Americans pursued rapprochement in the region, it wouldn’t have left the region unstable and Afghanistan more hostile, aggressive and divided than it was in 2001 when the American forces entered the region.

Experts have analyzed the region, the Afghan war and the American adventurism with a defense strategy and foreign policy lens. The Americans fought the war for two decades but while minor skirmishes and limited warfare continued in some parts of Afghanistan, the last decade in particular did not involve much fighting. The American presence in the region was not as much to decimate the Taliban as much as it was to contain them while it committed to rebuild the wartorn country. The Americans committed to bringing back peace and rebuilding broken institutions, which one would imagine did not take place. Political stability did not return and while analysts look toward political decisions and mistakes as factors leading to instability, the causes are more economic than political.

Rebuilding Afghanistan meant creating economic institutions, expanding resources and providing vulnerable groups with sustainable sources of employment and income generation. The Afghan economy has been little reviewed and analyzed because people have not focused on how the economy has behaved under the US and what implications has the economic exclusion of certain groups had on the developing security situation in the region.

GDP growth suffered during Covid but the economic losses borne by Afghanistan are not magnified when looked in comparison with losses suffered by the entire south Asian region. Pakistan has done better to allay the economic fears of Covid compared to the regional average while India has suffered badly at the hands of the deadly virus. Afghanistan, under the American policy influence, has done as well as the region did in 2020; its GDP shrunk by around 1.9%. It had been growing on an average of 2.9% for the five years prior to the onslaught of Covid, a rate that disputes the American claims of investing in economic growth and rebuilding of institutions in the country. Many parts of Afghanistan that are directly controlled by the Taliban may not contribute to the national economy and would instead be diluting the economic gains made by the Americans and the Afghan government in areas that are administratively managed by them. However, the fact that peace has not returned does not completely prove the claim that the Americans fell short of their goals in Afghanistan. Instead, what bears greater reference to American performance in the region is the shaky and failing economy of Afghanistan.

In the first five years of American presence in Afghanistan; that is between 2003 and 2007, GDP grew by 8% on average with 2005 and 2007 as outliers when GDP grew abnormally, 11% and 13%, respectively. The Afghan population was nearly 21 million in 2001, which had nearly doubled to 39 million in 2019. With a population of around 20-25 million in the first five years of American presence in Afghanistan, GDP per capita growth had averaged 4.3%. GDP per capita, in US dollar terms was, around USD 180 in 2002 which increased significantly to USD 508 in 2020. The increase is substantial and while it is indicative of growth and welfare that the American policy and overseas development assistance may have generated in Afghanistan. However, if one looks at the gains that had been achieved at the close of Obama’s first term in office when the policy change to adopt austerity measures in the US and to transition towards an American exit from Afghanistan was made, GDP per capita had maximized to USD 641. With a population that is still under 40 million, the Afghan GDP per capital speaks volumes about how much and how well the Americans have done to resuscitate the afghan economy and bring vulnerable groups into the economic fold. Urban population (as a proportion of total population) has been literally stagnant. From 23% in 2002 to nearly 26% today, the proportion of urban population reflects the lack of city development and growth that has taken place. Much of that can be attributed to Taliban presence in many rural towns however, suburbs of cities administratively controlled by the Afghan government have also not attained urban characteristics at the pace at which one could have imagined that the Americans would have been able to construct urban infrastructure.

The economy has moved with changes in the foreign direct investment and overseas development assistance which implies that indigenous capacity in the economy to generate growth has not been created. Growth has only emerged at times when foreign assistance was available and it disappeared at times when the direct economic assistance of the Americans was not readily available. Health and education statistics also tell a story about the American economic performance. In some of my articles on this page in the future, I would engage with the Afghan development statistics, most particularly its social indicators on health, education and poverty. The effort would will be aimed at building a narrative about the Afghan economy, which is largely absent from the literature.

The writer is an economist based in Islamabad. He tweets @AsadAijaz