Iran votes today to elect the country’s eighth president. The Guardian Council, a largely unelected 12-member body which vets candidates, was particularly gratuitous in scrutinising and axing candidates for this election. It short-listed only seven candidates to run for the president’s office: five hardliners, one moderate and one reformist.

On Wednesday, two hardliners, former nuclear negotiator Saeed Jalili and lawmaker and media owner Alireza Zakani dropped out of the race to consolidate the conservative vote. Reformist former vice president Mohsen Mehralizadeh also withdrew, leaving former Central Bank governor Abdolnasser Hemmati as the only moderate candidate in the race.

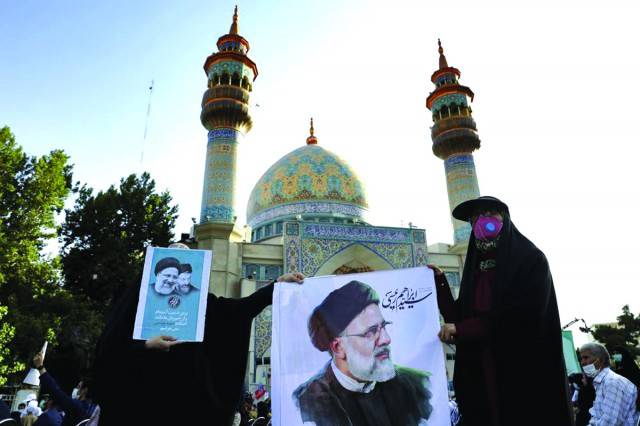

This basically narrows the race to a contest between Ebrahim Raisi, head of judiciary (Chief Justice) and Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s protégé, and Hemmati. In fact, since May 25 when the Council approved seven candidates for the president’s election, there has been much commentary with reference to system rigging in favour of Raisi. This was fuelled by the decision of the Council to knock out Ali Larijani, a former officer in the Revolutionary Guards Corps and former speaker of parliament who belongs to the powerful Larijani family and whose brother Sadeq Larijani is a member of the Guardian Council. Observers believe Larijani was taken out of the race because given his vast and diverse political and administrative experience, he would have overshadowed Raisi and also split the conservative vote.

The Council’s decision was bitterly criticised by outgoing President Hassan Rouhani and also former President Mohammad Khatami. On May 30, Tehran’s Prosecutor Ali Alghasi Mehr told presidential candidates “not to cross the Islamic Republic’s red lines,” saying that violations “will be strictly dealt with.” This was again seen as Raisi — who has not stepped down as head of judiciary despite running for president — using his power to pressure other candidates. While other candidates kept quiet, Mehralizadeh, who dropped out on Wednesday, did not hold his punches and said “If the Chief Justice is worried that criticising him in this unfair competition would be treated as criticising the Judiciary, he had better resign his post as Judiciary Chief or withdraw his candidacy for the Presidential election.”

Polls after the Guardian Council decision also showed that voter interest in the election plunged on the back of the widely-held view that the clerical and conservative establishment was queering the pitch in favour of Raisi. There are 53.9 million eligible voters in Iran, split nearly equally into 29.33 million women and 29.98 million men. This year 1.3 million voters (aged 18 and above) will also be voting for the first time.

In fact, the prospect of a low voter turnout has somewhat shaken the establishment. In a recent televised speech, Khamenei warned of a foreign conspiracy to undermine the vote. Reference to foreign hands is a regularly used motif in Iran’s controlled and directed politics. Voter turnout is often projected as validation of Iran’s complicated, two-tiered system in which supremacy of the Supreme Leader creates an asymmetrical power structure and leaves little space for the president and his team to push their agenda.

There’s a dilemma in this, however. Voter apathy was running deep even before the Guardian Council eviscerated strong contenders like Larijani. But lower turnout also helps Raisi since a higher turnout could favour Hemmati and his moderate agenda. There’s precedence for this. Mohammad Khatami upset the establishment’s favoured candidate, the conservative Speaker of Parliament, Ali Akbar Nateq-Nouri, in the May 1997 elections, winning 70 per cent of the vote. The turnout in that election was 80 per cent. He was re-elected on June 8, 2001 for a second term. Khatami ran on a platform of liberalisation and reform. During his two terms, he advocated freedom of expression, tolerance, constructive diplomatic relations with other states, and an economic policy that supported free market and foreign investment.

Iranians have been hit hard by the sanctions and the pain has only increased because of the added impact of Covid-19 on the economy and jobs. Over 60 percent of Iran’s population is under 30 years old. This bulge wants reforms but also sees that the system, as currently configured, vests ultimate power in the person of the Supreme Leader. This said, after the first reactions to the Guardian Council’s decision to axe many eligible candidates, there seems to be a growing sense among the voters that the only way to frustrate the system and its candidate, Raisi, is to turn out in large numbers and not allow the conservative vote to steal the show. Whether this will actually happen today remains to be seen.

After the death of Khomeini, the late Hashmi Rafsanjani had eased many social and cultural controls, but not much movement has happened since then and political dissent is not tolerated. Mohamed Khatami and Hasan Rouhani both tried to open up the system but while being successful in some ways, failed in breaking the stranglehold of the Supreme Leader and his control of the coercive and legal apparatus of the state. Nonetheless, there are safety valves in Iran to let out steam, though challenging the system remains parlous. There’s criticism of the government and its policies and politicians regularly criticise each other. Sometimes there are oblique references to the Supreme Leader too or the selected bodies that monitor and control the form and working of Iran’s regulated ‘democracy’. But crossing the red lines can be hazardous.

For instance, at a press conference after the Guardian Council approved the original seven candidates, Abdolreza Rahmani Fazli, the interior minister, admitted that there was no real contest in the upcoming presidential elections. “The actual competition in the elections is not a very serious one...considering the actions of the Guardian Council. We can say that the reasons are the weak competition and the coronavirus situation.” As I noted earlier, former President Khatami also slammed the Council, saying the secretive way in which it works is a danger to the republican principle enshrined in the constitution.

So, there are voices. But it helps if one is, or was, a political heavyweight.

Interestingly, the one president who tried to challenge Khamenei’s supremacy was Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a hardliner. As a conservative and blue-eyed of Khamenei, Ahmadinejad sought to build up a power base among the same constituencies that undergird Supreme Leader’s support base — i.e., the military, judiciary and the security agencies. He thought that by getting their support he could strengthen his presidency and by extension weaken Khamenei’s base. It did not work out. When he clashed with Khamenei on the issue of some appointments, it became very clear that he hadn’t been able to make inroads into Khamenei’s constituency.

Raisi is also tipped to be Khamenei’s successor for the position of Supreme Leader. The presidency, which he previously lost to Rouhani, is supposed to train him for that role. He couldn’t defeat Rouhani in 2017. Given Khamenei’s frail health, it is important for Iran’s unelected power centres to ensure his victory this time round. For Hemmati to upset this plan despite the Council’s system rigging in Raisi’s favour, he would need the kind of turnout and vote which helped Khatami defeat Nateq-Nouri. That’s a big ask.

Even if Hemmati forces a runoff, that could help his cause in the second round. Today will be fascinating to watch!

The writer is a former News Editor of The Friday Times. He tweets @ejazhaider

On Wednesday, two hardliners, former nuclear negotiator Saeed Jalili and lawmaker and media owner Alireza Zakani dropped out of the race to consolidate the conservative vote. Reformist former vice president Mohsen Mehralizadeh also withdrew, leaving former Central Bank governor Abdolnasser Hemmati as the only moderate candidate in the race.

This basically narrows the race to a contest between Ebrahim Raisi, head of judiciary (Chief Justice) and Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s protégé, and Hemmati. In fact, since May 25 when the Council approved seven candidates for the president’s election, there has been much commentary with reference to system rigging in favour of Raisi. This was fuelled by the decision of the Council to knock out Ali Larijani, a former officer in the Revolutionary Guards Corps and former speaker of parliament who belongs to the powerful Larijani family and whose brother Sadeq Larijani is a member of the Guardian Council. Observers believe Larijani was taken out of the race because given his vast and diverse political and administrative experience, he would have overshadowed Raisi and also split the conservative vote.

The Council’s decision was bitterly criticised by outgoing President Hassan Rouhani and also former President Mohammad Khatami. On May 30, Tehran’s Prosecutor Ali Alghasi Mehr told presidential candidates “not to cross the Islamic Republic’s red lines,” saying that violations “will be strictly dealt with.” This was again seen as Raisi — who has not stepped down as head of judiciary despite running for president — using his power to pressure other candidates. While other candidates kept quiet, Mehralizadeh, who dropped out on Wednesday, did not hold his punches and said “If the Chief Justice is worried that criticising him in this unfair competition would be treated as criticising the Judiciary, he had better resign his post as Judiciary Chief or withdraw his candidacy for the Presidential election.”

Polls after the Guardian Council decision also showed that voter interest in the election plunged on the back of the widely-held view that the clerical and conservative establishment was queering the pitch in favour of Raisi. There are 53.9 million eligible voters in Iran, split nearly equally into 29.33 million women and 29.98 million men. This year 1.3 million voters (aged 18 and above) will also be voting for the first time.

In fact, the prospect of a low voter turnout has somewhat shaken the establishment. In a recent televised speech, Khamenei warned of a foreign conspiracy to undermine the vote. Reference to foreign hands is a regularly used motif in Iran’s controlled and directed politics. Voter turnout is often projected as validation of Iran’s complicated, two-tiered system in which supremacy of the Supreme Leader creates an asymmetrical power structure and leaves little space for the president and his team to push their agenda.

There’s a dilemma in this, however. Voter apathy was running deep even before the Guardian Council eviscerated strong contenders like Larijani. But lower turnout also helps Raisi since a higher turnout could favour Hemmati and his moderate agenda. There’s precedence for this. Mohammad Khatami upset the establishment’s favoured candidate, the conservative Speaker of Parliament, Ali Akbar Nateq-Nouri, in the May 1997 elections, winning 70 per cent of the vote. The turnout in that election was 80 per cent. He was re-elected on June 8, 2001 for a second term. Khatami ran on a platform of liberalisation and reform. During his two terms, he advocated freedom of expression, tolerance, constructive diplomatic relations with other states, and an economic policy that supported free market and foreign investment.

Iranians have been hit hard by the sanctions and the pain has only increased because of the added impact of Covid-19 on the economy and jobs. Over 60 percent of Iran’s population is under 30 years old. This bulge wants reforms but also sees that the system, as currently configured, vests ultimate power in the person of the Supreme Leader. This said, after the first reactions to the Guardian Council’s decision to axe many eligible candidates, there seems to be a growing sense among the voters that the only way to frustrate the system and its candidate, Raisi, is to turn out in large numbers and not allow the conservative vote to steal the show. Whether this will actually happen today remains to be seen.

After the death of Khomeini, the late Hashmi Rafsanjani had eased many social and cultural controls, but not much movement has happened since then and political dissent is not tolerated. Mohamed Khatami and Hasan Rouhani both tried to open up the system but while being successful in some ways, failed in breaking the stranglehold of the Supreme Leader and his control of the coercive and legal apparatus of the state. Nonetheless, there are safety valves in Iran to let out steam, though challenging the system remains parlous. There’s criticism of the government and its policies and politicians regularly criticise each other. Sometimes there are oblique references to the Supreme Leader too or the selected bodies that monitor and control the form and working of Iran’s regulated ‘democracy’. But crossing the red lines can be hazardous.

For instance, at a press conference after the Guardian Council approved the original seven candidates, Abdolreza Rahmani Fazli, the interior minister, admitted that there was no real contest in the upcoming presidential elections. “The actual competition in the elections is not a very serious one...considering the actions of the Guardian Council. We can say that the reasons are the weak competition and the coronavirus situation.” As I noted earlier, former President Khatami also slammed the Council, saying the secretive way in which it works is a danger to the republican principle enshrined in the constitution.

So, there are voices. But it helps if one is, or was, a political heavyweight.

Interestingly, the one president who tried to challenge Khamenei’s supremacy was Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, a hardliner. As a conservative and blue-eyed of Khamenei, Ahmadinejad sought to build up a power base among the same constituencies that undergird Supreme Leader’s support base — i.e., the military, judiciary and the security agencies. He thought that by getting their support he could strengthen his presidency and by extension weaken Khamenei’s base. It did not work out. When he clashed with Khamenei on the issue of some appointments, it became very clear that he hadn’t been able to make inroads into Khamenei’s constituency.

Raisi is also tipped to be Khamenei’s successor for the position of Supreme Leader. The presidency, which he previously lost to Rouhani, is supposed to train him for that role. He couldn’t defeat Rouhani in 2017. Given Khamenei’s frail health, it is important for Iran’s unelected power centres to ensure his victory this time round. For Hemmati to upset this plan despite the Council’s system rigging in Raisi’s favour, he would need the kind of turnout and vote which helped Khatami defeat Nateq-Nouri. That’s a big ask.

Even if Hemmati forces a runoff, that could help his cause in the second round. Today will be fascinating to watch!

The writer is a former News Editor of The Friday Times. He tweets @ejazhaider