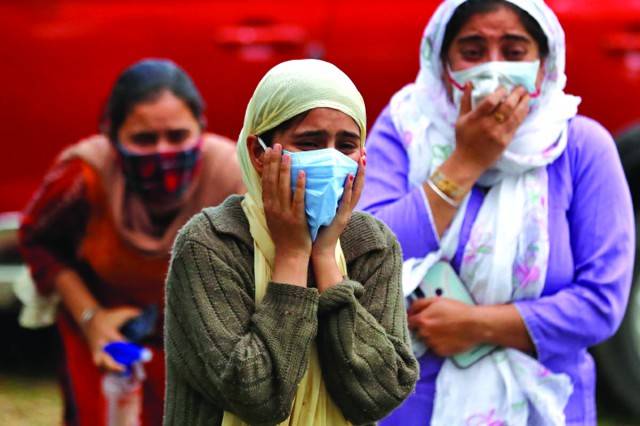

India is in the midst of a deadly Covid storm, which is claiming thousands of lives each day. Considered as a ‘second wave,’ the virus is causing devastation across both rural and urban spheres in India. This unprecedented health crisis which has engulfed the country is not a plain occurrence; rather it is the result of multiple institutional failures, ranging from pillars of democracy to every secondary institution wherein officers in charge found any pecuniary or other benefit by dancing at the whims of the ruling party at the Centre.

This article aims to highlight the role of excessive advertisement, awards and post-retirement appointments and explains how they are responsible for the present deep mess we are in.

In doing so we will take a cue from the Economics of Information. According to Stigler (1961), in modern times, advertising is one of the obvious methods of identifying potential buyers and sellers in a market. In the age of Information and Communication Technology, from business to politics, almost everything is advertised through digital media. It is not surprising that year after year, it is found that the money spent by political parties on advertising is increasing. During 2019-20 the amount spent on advertising by one of the main political parties in India stood at around Rs1.95 crore per day. This in a country where, according to United Nations Food Programme, levels of poverty, food insecurity, malnutrition, inequality and social exclusion are very high. The major share of the money spent on advertisement goes to the coffers of citizens on higher steps of the political and economic ladder.

Media model

The media’s revenue model in India is mostly advertisement-driven. This becomes problematic when the majority of advertisements either come from the government or from companies which are close to the government. This symbiotic relation between media houses, government and business houses cons the system and an essential check to the system is eroded. Furthermore, it has become lucrative for star anchors to act as propaganda machines, as they prefer to question opposition leaders rather than the government. Similarly, business houses close to the government have found their fortunes to have doubled. They have also been able to flout the rules without any costs. Some corporates even promoted their business with the prime minister as brand ambassador, though they later apologised. In any other functioning democracy, this would have garnered serious criticism and certainly have affected both the image and the credibility of the ruling party.

Raghuram Rajan (2019) notes that unlike the United States, where the private sector criticises government policies on issues not directly related to business, in India major business houses largely applaud government policy. The government, no matter how ineffective it is in delivery of public goods, explores a carrot or stick approach to make the private sector fall in line. Importantly, Rajan (2019) observes that the party in power, when in need of election financing, needs only ask.

Institutional decay

Media and business houses are not alone. Much blame lies on the judiciary and election commission. The judiciary played the greatest role in the systematic erosion of democracy by protecting government interests over citizen priorities. Be it the abrogation of autonomy of Jammu and Kashmir, Electoral Bonds, or hypocritic stands on individual liberty, the judiciary has not missed an opportunity to act as the judicial stamp on anti-citizen legislations. Recently, the apathy by the judiciary reached such levels that it did not consider shortage of oxygen in the midst of a pandemic as an urgent matter and instead chose to adjourn it.

The agents at the helm of these institutions enjoy many post-retirement benefits. A case in point is the nomination of former Chief Justice of India (CJI) to the upper house of the Parliament just a few months after his retirement. The same CJI headed the bench which delivered the Ayodha judgement in favour of the party which had a role in the demolition of the Mosque. The judgement over three months after the abrogation of Article 370 – and political and civil citizen rights were violated en masse. Yet the highest court did not feel any urgency to restore citizen rights. As of this date it is yet to deliver the final verdict regarding the constitutionality of the Article 370’s abrogation.

Another contentious and important verdict on which the future of Indian democracy lies is the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). Had the higher court performed its duties impartially, the riots in Delhi could have been avoided. The same is true as regards electoral bonds. The opaqueness of the process is against democratic norms – and makes getting elected a function of how much money is spent on election-related advertisements. The voter no longer exercises the free choice – and the very purpose of universal adult franchise is defeated. The combination of poor business reputation and electoral bond opaqueness highlights how urgent the electoral bond verdict is for Indian democracy. The judiciary is so compromised that even a simple warning to the government is considered heroic. A case in point is the recent judgement by Justice Chandrachud’s bench for warning the government against criminalising the sharing of desperate calls to help on social media. Of late there are some optimistic signs of the Supreme Court functioning as a guardian of citizen rights.

The Election Commission of India (ECI), like the judiciary, is a constitutional body. Its role is of paramount importance as hardly any year passes without some election taking place. Yet over a period of time, the commission has become more partisan – and its independence is increasingly questioned. It has to be mentioned here that one of the major reasons mentioned for democracy backsliding by the V- Dem Institute (a Sweden-based think-tank) is the decline in the ECI’s autonomy. Similarly the Freedom House, which ranks countries around the world as regards political rights and civil liberties, rated a 40 percent weightage to political rights and 60 percent to civil liberties. On the issue of fairness of the ECI it praises its independent nature but mentions that “In 2019, however, its impartiality and competence were called into question. The panel’s decisions concerning the timing and phasing of national elections, and allegations of selective enforcement of the Model Code of Conduct, which regulates politicians’ campaign behaviour and techniques, suggested bias toward the ruling BJP”. The same report also labels India as partly free. The other major report analysing the state of democracy worldwide is The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy index. In its 2020 report it characterises India as a flawed democracy. Though on electoral process and pluralism, India maintains its score of 8.67, the report mentions pressure on democratic norms since 2015.

Society is also to blame for much of the decline in accountability and democratic norms. Even leaders of some political parties supported one or other move. Was the onslaught on constitutional rights of one group not celebrated by the other, the government would not have been on overdrive by formulating anti-citizen polices. Citizens remained so disorganised and divided on parochial lines that the government felt no significant, systematic backlash on its policies from the public–––be it Demonetisation or the Ladakh standoff, among others. It is however naïve to argue that there was no opposition from society regarding anti-government policies. There were many groups which tried to put pressure on the government; however, those voices were either miniscule or marginalised by media. Any voice critical of government polices was labelled as anti-national, tukde tukde gang among others. Crises are periods when the vibrancy of society is crucial for a coordinated response. In highly polarised societies, crises can create havoc as citizens don’t lend a helping hand to each other.

In the states ruled by the BJP, fault lines are actively exploited even when people are gasping for oxygen and failing to get a bed. In the state of Gujrat, some leaders of the ruling party objected to the presence of Muslim volunteers at the crematorium. Similarly, in Bangalore, a member of parliament stoked controversy by targeting staff from minority communities. One positive take from the present health crises is that the many fault lines in society became blurred. As The Economist (2021) notes: “the government may have fallen short but civil society has stepped up”.

Awards provide recognition to persons thought to best possess some distinguishing qualities. Awards play an important signaling role with regard to capabilities of both individuals or institutions. In the present era of information explosion and social media, awards are often used to further a particular view point. In the context of India, the information content of an award is highly distorted, due to faulty digital literacy and á deluge of fake news. The common mass takes every WhatsApp forward as true.

The conferment of awards is another mechanism by which the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) furthered its anti-citizen agenda. Consider the case of the Philip Kotler award given to the Prime Minister by the World Management Summit. The event was co-sponsored among others by Gas Authority, India Limited (GAIL), Patanjali and Republic TV. The government of India reciprocated the favour by awarding Padma Bhushan, the person who conferred the Kotler award on behalf of Professor Kotler – as reported by various media outlets. Similarly, Uttar Pradesh, which has the worst track record with respect to law and order, is shown day in and out by media as the best performing state under Yogi Adityanath.

Adityanath, who heads the Uttar Pradesh state, has been widely criticized for using hate speech. Under his rule, state agencies confiscated property of citizens who took part in the anti-citizenship amendment act. The worst act of brutishness by the Uttar Pradesh government occurred when a rape victim who died at the AIIMS hospital was buried during the night hours and that too without the consent of her parents. The state’s high-handedness can be measured by how it chose to arrest a journalist for the only crime of doing its job of covering the story related to Hathras rape. The same state made it criminal to highlight government incompetence on social media with regard to handling covid. Yet a national survey by the India Today group media shows Uttar Pradesh as next powerhouse and Adityanath as the best performing Chief-Minister. These surveys are then sugar coated by well-oiled Information Technology (IT) cells and forwarded on infinite Whatsapp groups of party workers and common citizens. The social media in general and WhatsApp in particular are of immense value for the political parties. As stated by one member of parliament: “we can make any message right or wrong viral in a matter of few seconds”.

That brings us to the third part of how Covid-19 is related to excessive advertisement and awards. Though covid itself and the causalities caused by it can be labelled as a health issue, the phenomenon is strongly tied with the systematic destruction of institutions, excessive centralisation and abuse of power. The powerful media houses relied on government feeds and shifted the blame onto minorities and opposition. Most channels even went to the extent of praising the leadership skills of prime minister – in handling the covid very well and proving the naysayers wrong. Now when the virus went out of control due to policy blunders like mega-rallies, the Kumbh mela and the premature declaration of success over the virus, the media has found the system as a new target. Due to pecuniary and employment benefits they are afraid to speak truth to power, as doing so will amount to losing a job and other costs.

Arshid Hussain Peer and Muneeb Yousuf are researchers based in New Delhi

This article aims to highlight the role of excessive advertisement, awards and post-retirement appointments and explains how they are responsible for the present deep mess we are in.

In doing so we will take a cue from the Economics of Information. According to Stigler (1961), in modern times, advertising is one of the obvious methods of identifying potential buyers and sellers in a market. In the age of Information and Communication Technology, from business to politics, almost everything is advertised through digital media. It is not surprising that year after year, it is found that the money spent by political parties on advertising is increasing. During 2019-20 the amount spent on advertising by one of the main political parties in India stood at around Rs1.95 crore per day. This in a country where, according to United Nations Food Programme, levels of poverty, food insecurity, malnutrition, inequality and social exclusion are very high. The major share of the money spent on advertisement goes to the coffers of citizens on higher steps of the political and economic ladder.

Media model

The media’s revenue model in India is mostly advertisement-driven. This becomes problematic when the majority of advertisements either come from the government or from companies which are close to the government. This symbiotic relation between media houses, government and business houses cons the system and an essential check to the system is eroded. Furthermore, it has become lucrative for star anchors to act as propaganda machines, as they prefer to question opposition leaders rather than the government. Similarly, business houses close to the government have found their fortunes to have doubled. They have also been able to flout the rules without any costs. Some corporates even promoted their business with the prime minister as brand ambassador, though they later apologised. In any other functioning democracy, this would have garnered serious criticism and certainly have affected both the image and the credibility of the ruling party.

Raghuram Rajan (2019) notes that unlike the United States, where the private sector criticises government policies on issues not directly related to business, in India major business houses largely applaud government policy. The government, no matter how ineffective it is in delivery of public goods, explores a carrot or stick approach to make the private sector fall in line. Importantly, Rajan (2019) observes that the party in power, when in need of election financing, needs only ask.

The judiciary is so compromised that even a simple warning to the government is considered heroic

Institutional decay

Media and business houses are not alone. Much blame lies on the judiciary and election commission. The judiciary played the greatest role in the systematic erosion of democracy by protecting government interests over citizen priorities. Be it the abrogation of autonomy of Jammu and Kashmir, Electoral Bonds, or hypocritic stands on individual liberty, the judiciary has not missed an opportunity to act as the judicial stamp on anti-citizen legislations. Recently, the apathy by the judiciary reached such levels that it did not consider shortage of oxygen in the midst of a pandemic as an urgent matter and instead chose to adjourn it.

The agents at the helm of these institutions enjoy many post-retirement benefits. A case in point is the nomination of former Chief Justice of India (CJI) to the upper house of the Parliament just a few months after his retirement. The same CJI headed the bench which delivered the Ayodha judgement in favour of the party which had a role in the demolition of the Mosque. The judgement over three months after the abrogation of Article 370 – and political and civil citizen rights were violated en masse. Yet the highest court did not feel any urgency to restore citizen rights. As of this date it is yet to deliver the final verdict regarding the constitutionality of the Article 370’s abrogation.

Another contentious and important verdict on which the future of Indian democracy lies is the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). Had the higher court performed its duties impartially, the riots in Delhi could have been avoided. The same is true as regards electoral bonds. The opaqueness of the process is against democratic norms – and makes getting elected a function of how much money is spent on election-related advertisements. The voter no longer exercises the free choice – and the very purpose of universal adult franchise is defeated. The combination of poor business reputation and electoral bond opaqueness highlights how urgent the electoral bond verdict is for Indian democracy. The judiciary is so compromised that even a simple warning to the government is considered heroic. A case in point is the recent judgement by Justice Chandrachud’s bench for warning the government against criminalising the sharing of desperate calls to help on social media. Of late there are some optimistic signs of the Supreme Court functioning as a guardian of citizen rights.

The Election Commission of India (ECI), like the judiciary, is a constitutional body. Its role is of paramount importance as hardly any year passes without some election taking place. Yet over a period of time, the commission has become more partisan – and its independence is increasingly questioned. It has to be mentioned here that one of the major reasons mentioned for democracy backsliding by the V- Dem Institute (a Sweden-based think-tank) is the decline in the ECI’s autonomy. Similarly the Freedom House, which ranks countries around the world as regards political rights and civil liberties, rated a 40 percent weightage to political rights and 60 percent to civil liberties. On the issue of fairness of the ECI it praises its independent nature but mentions that “In 2019, however, its impartiality and competence were called into question. The panel’s decisions concerning the timing and phasing of national elections, and allegations of selective enforcement of the Model Code of Conduct, which regulates politicians’ campaign behaviour and techniques, suggested bias toward the ruling BJP”. The same report also labels India as partly free. The other major report analysing the state of democracy worldwide is The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy index. In its 2020 report it characterises India as a flawed democracy. Though on electoral process and pluralism, India maintains its score of 8.67, the report mentions pressure on democratic norms since 2015.

Uttar Pradesh, which has the worst track record with respect to law and order, is shown day in and out by media as the best performing state under Yogi Adityanath

Society is also to blame for much of the decline in accountability and democratic norms. Even leaders of some political parties supported one or other move. Was the onslaught on constitutional rights of one group not celebrated by the other, the government would not have been on overdrive by formulating anti-citizen polices. Citizens remained so disorganised and divided on parochial lines that the government felt no significant, systematic backlash on its policies from the public–––be it Demonetisation or the Ladakh standoff, among others. It is however naïve to argue that there was no opposition from society regarding anti-government policies. There were many groups which tried to put pressure on the government; however, those voices were either miniscule or marginalised by media. Any voice critical of government polices was labelled as anti-national, tukde tukde gang among others. Crises are periods when the vibrancy of society is crucial for a coordinated response. In highly polarised societies, crises can create havoc as citizens don’t lend a helping hand to each other.

In the states ruled by the BJP, fault lines are actively exploited even when people are gasping for oxygen and failing to get a bed. In the state of Gujrat, some leaders of the ruling party objected to the presence of Muslim volunteers at the crematorium. Similarly, in Bangalore, a member of parliament stoked controversy by targeting staff from minority communities. One positive take from the present health crises is that the many fault lines in society became blurred. As The Economist (2021) notes: “the government may have fallen short but civil society has stepped up”.

Awards provide recognition to persons thought to best possess some distinguishing qualities. Awards play an important signaling role with regard to capabilities of both individuals or institutions. In the present era of information explosion and social media, awards are often used to further a particular view point. In the context of India, the information content of an award is highly distorted, due to faulty digital literacy and á deluge of fake news. The common mass takes every WhatsApp forward as true.

The conferment of awards is another mechanism by which the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) furthered its anti-citizen agenda. Consider the case of the Philip Kotler award given to the Prime Minister by the World Management Summit. The event was co-sponsored among others by Gas Authority, India Limited (GAIL), Patanjali and Republic TV. The government of India reciprocated the favour by awarding Padma Bhushan, the person who conferred the Kotler award on behalf of Professor Kotler – as reported by various media outlets. Similarly, Uttar Pradesh, which has the worst track record with respect to law and order, is shown day in and out by media as the best performing state under Yogi Adityanath.

Adityanath, who heads the Uttar Pradesh state, has been widely criticized for using hate speech. Under his rule, state agencies confiscated property of citizens who took part in the anti-citizenship amendment act. The worst act of brutishness by the Uttar Pradesh government occurred when a rape victim who died at the AIIMS hospital was buried during the night hours and that too without the consent of her parents. The state’s high-handedness can be measured by how it chose to arrest a journalist for the only crime of doing its job of covering the story related to Hathras rape. The same state made it criminal to highlight government incompetence on social media with regard to handling covid. Yet a national survey by the India Today group media shows Uttar Pradesh as next powerhouse and Adityanath as the best performing Chief-Minister. These surveys are then sugar coated by well-oiled Information Technology (IT) cells and forwarded on infinite Whatsapp groups of party workers and common citizens. The social media in general and WhatsApp in particular are of immense value for the political parties. As stated by one member of parliament: “we can make any message right or wrong viral in a matter of few seconds”.

That brings us to the third part of how Covid-19 is related to excessive advertisement and awards. Though covid itself and the causalities caused by it can be labelled as a health issue, the phenomenon is strongly tied with the systematic destruction of institutions, excessive centralisation and abuse of power. The powerful media houses relied on government feeds and shifted the blame onto minorities and opposition. Most channels even went to the extent of praising the leadership skills of prime minister – in handling the covid very well and proving the naysayers wrong. Now when the virus went out of control due to policy blunders like mega-rallies, the Kumbh mela and the premature declaration of success over the virus, the media has found the system as a new target. Due to pecuniary and employment benefits they are afraid to speak truth to power, as doing so will amount to losing a job and other costs.

Arshid Hussain Peer and Muneeb Yousuf are researchers based in New Delhi