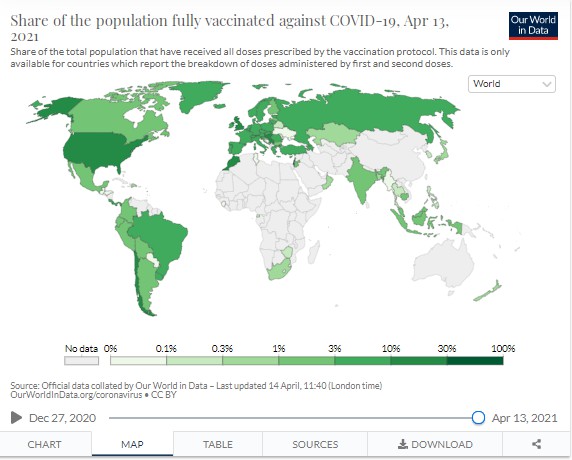

In some ways, vaccinations and the ability to access them will be the great new inequality, separating developed nations from those which wish they had developed by now.

I work in the field of economic development and so I am privy to discussions in which seasoned economists speak about the U-shaped recovery vs the V-shaped recovery as the best way to kick-start the global economy crippled by Covid-19.

None of us is completely clear on how to handle the pandemic. It follows its own lethal and unpredictable dynamic. Successive waves and new mutants are causing shut-downs all over the world. It is clear that there will be fear, uncertainty and anxiety about the future for many years to come. Returning to an earlier normal is a remote prospect. The new normal is one that is being dictated by Covid-19 and its variants.

Anecdotal examples confirm this: consider Singapore, which, until last week, was mask-less and now has gone into shutdown for a couple of weeks. In South Africa, colleagues have been contemplating going to Rwanda where there is easier access to vaccines, despite the former being one of the most developed countries in the region. In Turkey, foreigners are allowed in and out, partly to revive its economy, and yet its locals are being told to stay at home in an odd kind of discriminatory apartheid. Turkish beaches are open to foreigners, but locals are fined almost US$ 400 if police catch them lolling on the sand. My colleagues from Myanmar have been displaced – no longer safe at a time of political unrest. In the Middle East, colleagues from Jerusalem and Tel Aviv have to mute the phone during conference calls to stop the sound of guns, artillery and shelling disrupting our virtual meetings. That puts life into perspective.

The human cost is high these days. It would be difficult to find someone amongst us who does not wish for a better, peaceful world. And yet it seems that the world is becoming even more fractured than before – politically volatile, insensitive to the needs of the structurally excluded, and in some cases a Hobbesian dystopia where life is “nasty, brutish and short.”

There are some distressing facts about the human costs of the pandemic – for instance that 150 million people will go back into poverty, i.e. living on less than US$ 1 a day. That number will rise the more frequent the lockdowns. Sobering statistics are released daily: more than 168 million children have been out of school for more than nine months; and one-of-three students do not have access to remote learning. For those of us who complain about virtual learning and the ability to access it, we are fortunate that we have the means to educate and feed our children, to have access to vaccinations and to pay for them where they may not be available through government-sponsored programmes.

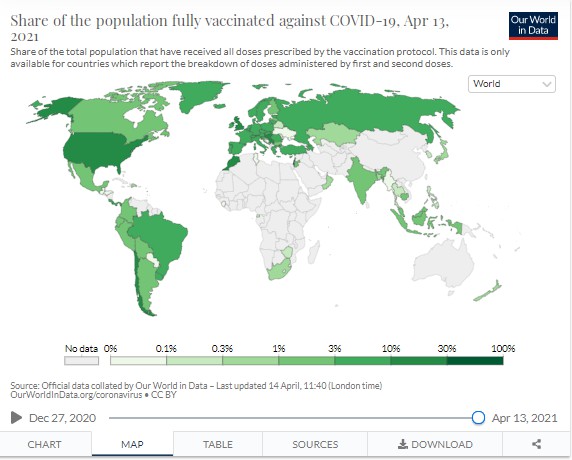

Larger richer countries have managed to muddle their way though. The US, for one, has engaged in mass vaccinations where anyone of any age can walk into pharmacies and get a jab. The mass vaccination schemes have gone from the eldest and most vulnerable to being available to everyone above the age of twelve. By this weekend in Washington, those who are fully vaccinated will be allowed to be mask-less in public places. In some areas of Washington DC, one can get a free beer or even cannabis after the injection. Many, to their chagrin, were unaware of this incentive, learning of it only after they had left the vaccination center!

China plans to vaccinate an additional 400 million people by the summer to celebrate the centenary of the Communist Party of China.

But what about the poorer countries and the pockets of people who cannot afford social distancing and stay-at-home policies and may contract this as the voiceless, faceless millions? India is a frightening example of this vulnerability, even though it has the capacity to produce vaccines locally and a thriving diaspora that has sent millions of dollars in aid. One shudders to think of those smaller economies which will be irreversibly affected because their governments neither have the policy apparatus nor the tools and resources to protect their citizens.

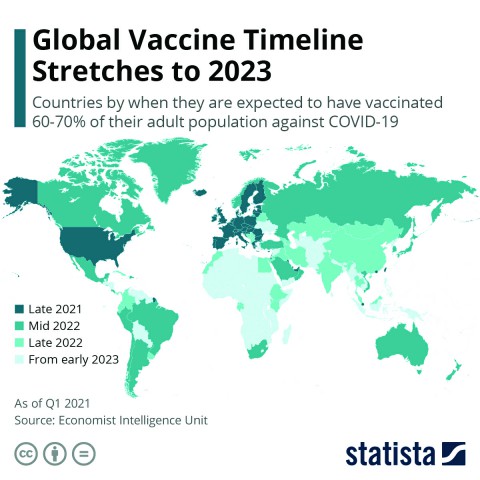

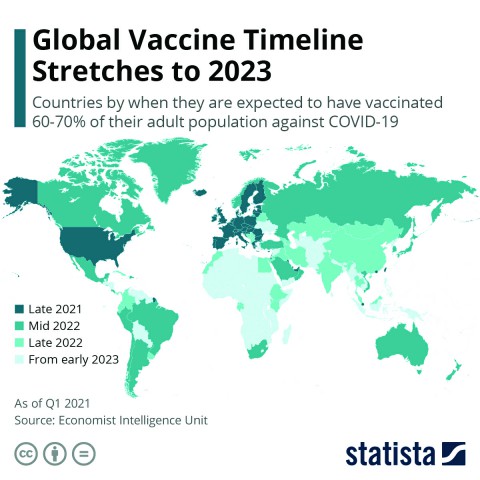

The latest data from the Duke Global Health Innovation Center Launch and Scale Speedometer, which monitors COVID-19 vaccine purchases, finds that high-income countries already own more than half of all global doses purchased, and it is estimated that there will not be enough vaccine doses to cover the world’s population until at least 2023. High-income countries, representing just a fifth of the global adult population, have purchased more than half of all vaccine doses, resulting in disparities between adult population share and doses purchased for all other country income groups.

And perhaps that is what a global system will mean – that we are ready to sacrifice a few million so that we can go back to economic growth and resilience. Vaccinations will be doled out unequally and be claimed first by those countries which have the ability to purchase them. Poorer nations will have to join the bread queue for vaccines.

All of us have blood running through our veins, regardless of our religion, race, caste or creed. It is not only humane but vital for us to remind ourselves of that shared humanity during these unsettling times. The ability to do so will require from us above all: empathy, grit, resilience and the ability to work cooperatively at an individual, collective and systemic level.

It is strange to think that in the 21st century, with all its technological advances, this pandemic has become the great economic and social equalizer. Only death is a more potent equalizer.

I work in the field of economic development and so I am privy to discussions in which seasoned economists speak about the U-shaped recovery vs the V-shaped recovery as the best way to kick-start the global economy crippled by Covid-19.

None of us is completely clear on how to handle the pandemic. It follows its own lethal and unpredictable dynamic. Successive waves and new mutants are causing shut-downs all over the world. It is clear that there will be fear, uncertainty and anxiety about the future for many years to come. Returning to an earlier normal is a remote prospect. The new normal is one that is being dictated by Covid-19 and its variants.

Anecdotal examples confirm this: consider Singapore, which, until last week, was mask-less and now has gone into shutdown for a couple of weeks. In South Africa, colleagues have been contemplating going to Rwanda where there is easier access to vaccines, despite the former being one of the most developed countries in the region. In Turkey, foreigners are allowed in and out, partly to revive its economy, and yet its locals are being told to stay at home in an odd kind of discriminatory apartheid. Turkish beaches are open to foreigners, but locals are fined almost US$ 400 if police catch them lolling on the sand. My colleagues from Myanmar have been displaced – no longer safe at a time of political unrest. In the Middle East, colleagues from Jerusalem and Tel Aviv have to mute the phone during conference calls to stop the sound of guns, artillery and shelling disrupting our virtual meetings. That puts life into perspective.

The human cost is high these days. It would be difficult to find someone amongst us who does not wish for a better, peaceful world. And yet it seems that the world is becoming even more fractured than before – politically volatile, insensitive to the needs of the structurally excluded, and in some cases a Hobbesian dystopia where life is “nasty, brutish and short.”

There are some distressing facts about the human costs of the pandemic – for instance that 150 million people will go back into poverty, i.e. living on less than US$ 1 a day. That number will rise the more frequent the lockdowns. Sobering statistics are released daily: more than 168 million children have been out of school for more than nine months; and one-of-three students do not have access to remote learning. For those of us who complain about virtual learning and the ability to access it, we are fortunate that we have the means to educate and feed our children, to have access to vaccinations and to pay for them where they may not be available through government-sponsored programmes.

High-income countries, representing just a fifth of the global adult population, have purchased more than half of all vaccine doses

Larger richer countries have managed to muddle their way though. The US, for one, has engaged in mass vaccinations where anyone of any age can walk into pharmacies and get a jab. The mass vaccination schemes have gone from the eldest and most vulnerable to being available to everyone above the age of twelve. By this weekend in Washington, those who are fully vaccinated will be allowed to be mask-less in public places. In some areas of Washington DC, one can get a free beer or even cannabis after the injection. Many, to their chagrin, were unaware of this incentive, learning of it only after they had left the vaccination center!

China plans to vaccinate an additional 400 million people by the summer to celebrate the centenary of the Communist Party of China.

But what about the poorer countries and the pockets of people who cannot afford social distancing and stay-at-home policies and may contract this as the voiceless, faceless millions? India is a frightening example of this vulnerability, even though it has the capacity to produce vaccines locally and a thriving diaspora that has sent millions of dollars in aid. One shudders to think of those smaller economies which will be irreversibly affected because their governments neither have the policy apparatus nor the tools and resources to protect their citizens.

The latest data from the Duke Global Health Innovation Center Launch and Scale Speedometer, which monitors COVID-19 vaccine purchases, finds that high-income countries already own more than half of all global doses purchased, and it is estimated that there will not be enough vaccine doses to cover the world’s population until at least 2023. High-income countries, representing just a fifth of the global adult population, have purchased more than half of all vaccine doses, resulting in disparities between adult population share and doses purchased for all other country income groups.

And perhaps that is what a global system will mean – that we are ready to sacrifice a few million so that we can go back to economic growth and resilience. Vaccinations will be doled out unequally and be claimed first by those countries which have the ability to purchase them. Poorer nations will have to join the bread queue for vaccines.

All of us have blood running through our veins, regardless of our religion, race, caste or creed. It is not only humane but vital for us to remind ourselves of that shared humanity during these unsettling times. The ability to do so will require from us above all: empathy, grit, resilience and the ability to work cooperatively at an individual, collective and systemic level.

It is strange to think that in the 21st century, with all its technological advances, this pandemic has become the great economic and social equalizer. Only death is a more potent equalizer.