Translator’s note:

Mustansar Hussain Tarar (b. 1939) is one of Pakistan’s most illustrious and important writers, and one of the greatest living Urdu writers. He made his name as a pathbreaking travelogue-writer in the 1950s, and then began writing novels in the early 1990s on themes as varied as the importance of rivers in the sustenance of ancient civilisations, the changing social and cultural fabric of Punjab over the years, forbidden romance, the downfall of the Soviet Union and how it affected a whole generation of idealists in South Asia, the Taliban phenomenon, days and nights of COVID–19, and even a Punjabi novel, acclaimed as the first modern one in the language.

In terms of sheer variety of topics, his closest associate is perhaps the equally iconic Urdu writer Quratulain Hyder. What has perhaps prevented the work of Tarar from receiving its due globally is a lack of translations into English. However, one of his novels Lenin for Sale: Ay Ghazaal-i-Shab has just been published in translation, and three others are in the process of being translated.

March 1 this year marked Tarar’s 82nd birthday while April 4 last month marked the 42nd anniversary of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s execution, and to mark the occasion, here is an exclusive translation of one of his earliest – and perhaps longest – stories, published as part of a short-story collection in the late 1970s or early ‘80s. The writer expressed a wish to have this story translated into English. Tarar told me in a recent conversation that this story was a metaphor for Pakistan’s worst military dictatorship, the Gen Zia-ul-Haq regime, which overthrew the democratically-elected government of Bhutto and executed him. As the reader will find out, the story offers a compelling argument against capital punishment. (RN)

A guide of the Tourism Department, leading a crowd of local and foreign tourists through the red pillars, glass palaces, gardens, halls and underground routes of the historic building entered the museum of ancient weapons. ‘Ladies and gentlemen,’ he directed their attention towards the revolvers, bayonets, spears, swords, shields, armours etc. ‘These bayonets, which we have kept in exhibit after polishing, if they are squeezed, rivers of blood will stream out, and these swords have passed through backbones like fingers through butter. On the mouths of these cannons, the rebels … forgive me, the nationalists were tied and blown up. And thus the rulers of those days were successful in making a strong and positive government. These are the weapons, fearing which, the people walked hunchbacked before the army, but the days of tyranny have passed. These injustices cannot even be imagined in the civilised age of today. Observe, for example, these clamps, which cut fingers like carrots entering a juice machine. Now we have sections in our national laws so that no one can even lift a finger at anyone. We should thank the Lord that we were not born in that savage period but breathe in the free atmosphere of an industrialised society. This historic museum has been preserved merely as a kind of memorial of oppression and injustice; so that today we can take pride in our good fortune. In those times, not only did wrathful rulers oppress the people but the army, in addition to fighting wars, massacred innocent civilians…imagine that…’

‘That the army, in those days, also fought wars?’

When Baba Bagloos woke up as morning dawned, he headed, as usual, to the kitchen, and sitting there digested a few morsels of stale roti, as slim as a kite, with gulps of tea. Then, as usual, he returned to his storeroom and, as usual, sat in a corner to stare at the ceiling. For how many thousand days had he been staring at this ceiling? He could not remember. Nobody remembered. When did the pulses of memory let go, who remembered? He had always been here; as if along with these high walls and storerooms the builders had also constructed Baba Bagloos. As long as the sunshine continued to spread in the courtyard, he would sit in his corner, jaws locked, face raised, sometimes enjoying tickling his white beard and then staring at the ceiling again. When the sunshine lifted upwards, measuring the walls of the courtyard lazily, he would come out and sit cross-legged on a dirty old mat and fix his eyes on the now-blue ceiling. Around him, the officials would pass nonchalantly; busy in their own work, dragging wounded bodies, throwing them into storerooms, repairing the arse-whippers, carrying blocks of ice which were to melt against the heat of naked bodies, they passed nonchalantly, like young couples passing by an old man sleeping on a garden bench, unconcerned and busy.

One evening, as usual, when Baba Bagloos came out in the courtyard from his storeroom, his sitting mat was not there and Bakka mashki, going round in a semi-circle in his bare feet, was sprinkling the courtyard with great urgency.

‘Is a king going to arrive?’ For Baba Bagloos, every officer visiting the prison from outside was a king.

Bakka mashki said ‘Huun’ while squeezing the soft leather of the water bottle in the mechanical manner of a sex worker and continued sprinkling water.

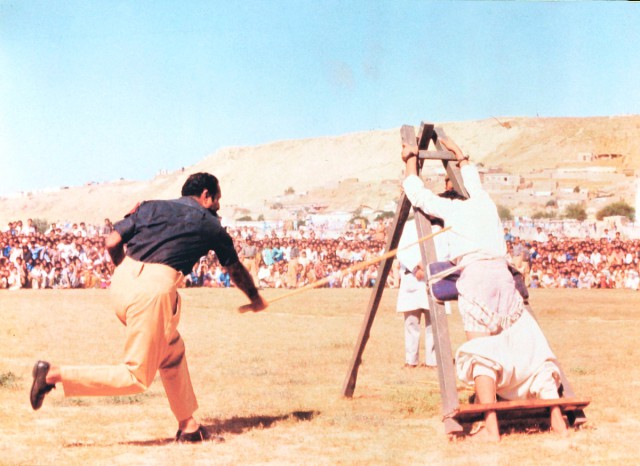

Baba sat in the corner without his mat and looked at the sky. When the sprinkling finished, a sofa set and few chairs were arranged in the courtyard; then the officials brought a wooden dosaanghi and fixed it in the centre of the courtyard. From afar, it looked as if this stand had been placed there for an artist who would presently arrive and, placing a canvas on it, would paint the prison. But instead of pictures, live models were kept on this stand. In the meantime, some heavily booted ones from the prison arrived with the Bari Sarkar who was walking in stooped fashion, and they sat on the sofas. Accompanying them was a doctor clad in a freshly-ironed white coat with a stethoscope dangling round his throat, like a cross hanging around the throat of a bishop who, having arrived late to grant a prayer of forgiveness to a death-row prisoner, is walking swiftly. They were laughing while conversing with each other, the heavy boots roaring, and the Bari Sarkar with relative caution.

‘I think we should begin now,’ a heavy boot addressed the Sarkar in an authoritative tone.

‘Sir what would be the harm if we have a cup of tea first, it’s almost four pm…’

Without waiting for an answer, the roar of Bari Sarkar’s ‘Tea’ reached the kitchen and an official came dragging the tea trolley into the courtyard (if the bodies of half-dead criminals were dragged on the wet courtyard without too much force, a little sprinkle would suffice the next day, the official thought). Tea was accompanied by other requisites.

‘The cake is excellent,’ the heavy boot said, wiping the crumbs from his moustache.

‘Sir, I had it brought from Mall Road. My own man brought it.’

‘I think that now…’

The Bari Sarkar cast a particular glance towards the storerooms as if the lifeless body of the prisoner tied in handcuffs of that glance had been recovered. Two soldiers were walking closely behind him. The doctor immediately got up and accosted the prisoner halfway as if to welcome him. He casually hammered the chest and looked behind. ‘How many?’

The Bari Sarkar could barely utter the word ‘fifteen’ between burps.

‘Okay.’ The doctor nodded his head promptly and then swiftly returned to sit on the sofa as if concerned that the tea in the cup would get cold.

The Bari Sarkar cast another meaningful glance at the storerooms and this time, an ugly-looking man drenched and shining in oil emerged from there, knotting his loincloth. He had a whip in his hand.

The prisoner was stripped naked and tied to the tripod. The langotiya looked towards the Bari Sarkar and upon the latter nodding his head began to stride towards the wall. Baba Bagloos was sitting near the wall, looking, not towards the sky but at this new spectacle.

In the last five or six years, the arrival of criminals at this prison had followed a schedule. But, in the last few months, the traffic had increased. Then suddenly on a summer morning, Inayat had told the baba in a secretive tone that the big boss of the Bari Sarkar had been put in jail and had been replaced by another Bari Sarkar. All prisoners had been freed the next day. A few weeks went by in great peace and security. The officials slept all day and the arse-whipper of the prison sarkar was growing stiff in the sunshine. But then suddenly, traffic resumed; not only that, but there was a regular traffic jam. Dozens of prisoners were stuffed into a single storeroom and the Bari Sarkar ordered several new arse-whippers. According to the sepoy, Inayat, he had never seen such festivities before.

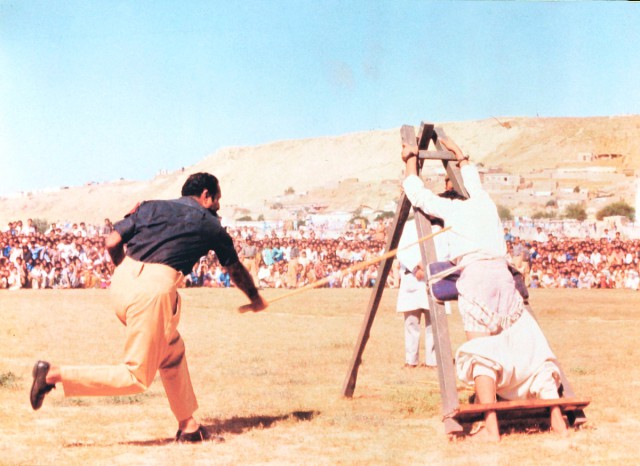

The langotiya, reaching Baba Bagloos, set off a sort of a cracker by jolting the whip, then fixing his gaze at the naked backside of the body tied at the tripod, raised a cry and with the measured steps of a horrible kind of dance ran, while fluttering his body, waved the whip as he neared the naked backside but suddenly stopped still, head bowed. He looked at the Bari Sarkar with eyes seeking forgiveness and slowly returned to stand near Baba Bagloos, and with the same special steps, ran in zigzag style but this time too, after reaching the proximity of the naked backside, waving the whip in the air, he suddenly stood still.

Bari Sarkar looked towards the heavy boots, extremely embarrassed and then roared, ‘Oye m***********! What has happened to you?’

‘Sarkar I am out of practice,’ the langotiya said, trembling, ‘by the grace of the maula I will not err this time, mai baap.’

He returned near Baba Bagloos with a remorseful face. His face darkened further before he ran and suddenly he turned and kicked Baba Bagloos’ waist. ‘I wondered why I missed the final step before lifting the whip. This m*********** is sitting here, that’s why! Sarkar, my run is a full twenty steps and this wretch is sitting at this twentieth step. Get up oye.’

Baba got up quietly. The langotiya looked with a junkie’s satisfaction at the prisoner, like a bowler who knows that his bowling start of twenty steps is now accurate and he will certainly uproot the wicket, and rip open the skin of the naked backside.

Baba Bagloos came to his storeroom and outside, Bari Sarkar and heavy boots kept drinking tea, eating cakes and the skin of the backside ripped open, changing into fine mincemeat.

Baba Bagloos had seen countless descriptions of torture making their mark on naked bodies before, but this spectacle was new. Within just a few days, however, the spectacle became really old. Dozens of people were whipped daily. Now the doctors, instead of regular check-ups would issue a certificate of ‘Fit for fifteen days’ by just observing a prisoner once; and the number of spectators also fell. Baba had only one objection to this new spectacle. He could not come out of his storeroom and sit in the courtyard when evening fell because the langotiya had a start of twenty steps and the twentieth step was Baba’s place.

(to be continued)

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and an award-winning translator and dramatic reader living in Lahore, where he is the President of the Progressive Writers Association. His most recent work is a contribution to ‘Out of Print Ten Years: An Anthology’ edited by Indira Chandrasekhar (Context, Westland Books, 2020).He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com

Note: Copyright Westland Books India 2020

Mustansar Hussain Tarar (b. 1939) is one of Pakistan’s most illustrious and important writers, and one of the greatest living Urdu writers. He made his name as a pathbreaking travelogue-writer in the 1950s, and then began writing novels in the early 1990s on themes as varied as the importance of rivers in the sustenance of ancient civilisations, the changing social and cultural fabric of Punjab over the years, forbidden romance, the downfall of the Soviet Union and how it affected a whole generation of idealists in South Asia, the Taliban phenomenon, days and nights of COVID–19, and even a Punjabi novel, acclaimed as the first modern one in the language.

In terms of sheer variety of topics, his closest associate is perhaps the equally iconic Urdu writer Quratulain Hyder. What has perhaps prevented the work of Tarar from receiving its due globally is a lack of translations into English. However, one of his novels Lenin for Sale: Ay Ghazaal-i-Shab has just been published in translation, and three others are in the process of being translated.

March 1 this year marked Tarar’s 82nd birthday while April 4 last month marked the 42nd anniversary of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s execution, and to mark the occasion, here is an exclusive translation of one of his earliest – and perhaps longest – stories, published as part of a short-story collection in the late 1970s or early ‘80s. The writer expressed a wish to have this story translated into English. Tarar told me in a recent conversation that this story was a metaphor for Pakistan’s worst military dictatorship, the Gen Zia-ul-Haq regime, which overthrew the democratically-elected government of Bhutto and executed him. As the reader will find out, the story offers a compelling argument against capital punishment. (RN)

A guide of the Tourism Department, leading a crowd of local and foreign tourists through the red pillars, glass palaces, gardens, halls and underground routes of the historic building entered the museum of ancient weapons. ‘Ladies and gentlemen,’ he directed their attention towards the revolvers, bayonets, spears, swords, shields, armours etc. ‘These bayonets, which we have kept in exhibit after polishing, if they are squeezed, rivers of blood will stream out, and these swords have passed through backbones like fingers through butter. On the mouths of these cannons, the rebels … forgive me, the nationalists were tied and blown up. And thus the rulers of those days were successful in making a strong and positive government. These are the weapons, fearing which, the people walked hunchbacked before the army, but the days of tyranny have passed. These injustices cannot even be imagined in the civilised age of today. Observe, for example, these clamps, which cut fingers like carrots entering a juice machine. Now we have sections in our national laws so that no one can even lift a finger at anyone. We should thank the Lord that we were not born in that savage period but breathe in the free atmosphere of an industrialised society. This historic museum has been preserved merely as a kind of memorial of oppression and injustice; so that today we can take pride in our good fortune. In those times, not only did wrathful rulers oppress the people but the army, in addition to fighting wars, massacred innocent civilians…imagine that…’

‘That the army, in those days, also fought wars?’

When Baba Bagloos woke up as morning dawned, he headed, as usual, to the kitchen, and sitting there digested a few morsels of stale roti, as slim as a kite, with gulps of tea. Then, as usual, he returned to his storeroom and, as usual, sat in a corner to stare at the ceiling. For how many thousand days had he been staring at this ceiling? He could not remember. Nobody remembered. When did the pulses of memory let go, who remembered? He had always been here; as if along with these high walls and storerooms the builders had also constructed Baba Bagloos. As long as the sunshine continued to spread in the courtyard, he would sit in his corner, jaws locked, face raised, sometimes enjoying tickling his white beard and then staring at the ceiling again. When the sunshine lifted upwards, measuring the walls of the courtyard lazily, he would come out and sit cross-legged on a dirty old mat and fix his eyes on the now-blue ceiling. Around him, the officials would pass nonchalantly; busy in their own work, dragging wounded bodies, throwing them into storerooms, repairing the arse-whippers, carrying blocks of ice which were to melt against the heat of naked bodies, they passed nonchalantly, like young couples passing by an old man sleeping on a garden bench, unconcerned and busy.

One evening, as usual, when Baba Bagloos came out in the courtyard from his storeroom, his sitting mat was not there and Bakka mashki, going round in a semi-circle in his bare feet, was sprinkling the courtyard with great urgency.

‘Is a king going to arrive?’ For Baba Bagloos, every officer visiting the prison from outside was a king.

‘Is a king going to arrive?’ For Baba Bagloos, every officer visiting the prison from outside was a king.

Bakka mashki said ‘Huun’ while squeezing the soft leather of the water bottle in the mechanical manner of a sex worker and continued sprinkling water.

Baba sat in the corner without his mat and looked at the sky. When the sprinkling finished, a sofa set and few chairs were arranged in the courtyard; then the officials brought a wooden dosaanghi and fixed it in the centre of the courtyard. From afar, it looked as if this stand had been placed there for an artist who would presently arrive and, placing a canvas on it, would paint the prison. But instead of pictures, live models were kept on this stand. In the meantime, some heavily booted ones from the prison arrived with the Bari Sarkar who was walking in stooped fashion, and they sat on the sofas. Accompanying them was a doctor clad in a freshly-ironed white coat with a stethoscope dangling round his throat, like a cross hanging around the throat of a bishop who, having arrived late to grant a prayer of forgiveness to a death-row prisoner, is walking swiftly. They were laughing while conversing with each other, the heavy boots roaring, and the Bari Sarkar with relative caution.

‘I think we should begin now,’ a heavy boot addressed the Sarkar in an authoritative tone.

‘Sir what would be the harm if we have a cup of tea first, it’s almost four pm…’

Without waiting for an answer, the roar of Bari Sarkar’s ‘Tea’ reached the kitchen and an official came dragging the tea trolley into the courtyard (if the bodies of half-dead criminals were dragged on the wet courtyard without too much force, a little sprinkle would suffice the next day, the official thought). Tea was accompanied by other requisites.

‘The cake is excellent,’ the heavy boot said, wiping the crumbs from his moustache.

‘Sir, I had it brought from Mall Road. My own man brought it.’

‘I think that now…’

The Bari Sarkar cast a particular glance towards the storerooms as if the lifeless body of the prisoner tied in handcuffs of that glance had been recovered. Two soldiers were walking closely behind him. The doctor immediately got up and accosted the prisoner halfway as if to welcome him. He casually hammered the chest and looked behind. ‘How many?’

The Bari Sarkar could barely utter the word ‘fifteen’ between burps.

‘Okay.’ The doctor nodded his head promptly and then swiftly returned to sit on the sofa as if concerned that the tea in the cup would get cold.

The Bari Sarkar cast another meaningful glance at the storerooms and this time, an ugly-looking man drenched and shining in oil emerged from there, knotting his loincloth. He had a whip in his hand.

The prisoner was stripped naked and tied to the tripod. The langotiya looked towards the Bari Sarkar and upon the latter nodding his head began to stride towards the wall. Baba Bagloos was sitting near the wall, looking, not towards the sky but at this new spectacle.

In the last five or six years, the arrival of criminals at this prison had followed a schedule. But, in the last few months, the traffic had increased. Then suddenly on a summer morning, Inayat had told the baba in a secretive tone that the big boss of the Bari Sarkar had been put in jail and had been replaced by another Bari Sarkar. All prisoners had been freed the next day. A few weeks went by in great peace and security. The officials slept all day and the arse-whipper of the prison sarkar was growing stiff in the sunshine. But then suddenly, traffic resumed; not only that, but there was a regular traffic jam. Dozens of prisoners were stuffed into a single storeroom and the Bari Sarkar ordered several new arse-whippers. According to the sepoy, Inayat, he had never seen such festivities before.

The langotiya, reaching Baba Bagloos, set off a sort of a cracker by jolting the whip, then fixing his gaze at the naked backside of the body tied at the tripod, raised a cry and with the measured steps of a horrible kind of dance ran, while fluttering his body, waved the whip as he neared the naked backside but suddenly stopped still, head bowed. He looked at the Bari Sarkar with eyes seeking forgiveness and slowly returned to stand near Baba Bagloos, and with the same special steps, ran in zigzag style but this time too, after reaching the proximity of the naked backside, waving the whip in the air, he suddenly stood still.

Bari Sarkar looked towards the heavy boots, extremely embarrassed and then roared, ‘Oye m***********! What has happened to you?’

‘Sarkar I am out of practice,’ the langotiya said, trembling, ‘by the grace of the maula I will not err this time, mai baap.’

He returned near Baba Bagloos with a remorseful face. His face darkened further before he ran and suddenly he turned and kicked Baba Bagloos’ waist. ‘I wondered why I missed the final step before lifting the whip. This m*********** is sitting here, that’s why! Sarkar, my run is a full twenty steps and this wretch is sitting at this twentieth step. Get up oye.’

Baba got up quietly. The langotiya looked with a junkie’s satisfaction at the prisoner, like a bowler who knows that his bowling start of twenty steps is now accurate and he will certainly uproot the wicket, and rip open the skin of the naked backside.

Baba Bagloos came to his storeroom and outside, Bari Sarkar and heavy boots kept drinking tea, eating cakes and the skin of the backside ripped open, changing into fine mincemeat.

Baba Bagloos had seen countless descriptions of torture making their mark on naked bodies before, but this spectacle was new. Within just a few days, however, the spectacle became really old. Dozens of people were whipped daily. Now the doctors, instead of regular check-ups would issue a certificate of ‘Fit for fifteen days’ by just observing a prisoner once; and the number of spectators also fell. Baba had only one objection to this new spectacle. He could not come out of his storeroom and sit in the courtyard when evening fell because the langotiya had a start of twenty steps and the twentieth step was Baba’s place.

(to be continued)

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and an award-winning translator and dramatic reader living in Lahore, where he is the President of the Progressive Writers Association. His most recent work is a contribution to ‘Out of Print Ten Years: An Anthology’ edited by Indira Chandrasekhar (Context, Westland Books, 2020).He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com

Note: Copyright Westland Books India 2020