The topic that has received the highest attention of writers, whether social scientists or writers of various genres of literature, in post-colonial South Asia is the Partition of Punjab in 1947. Though the historiography of the Partition is, in fact, largely a historiography of emotions of love, hatred, longing and loss, historians have their own ways to describe it. For example, Rabia Umar Ali, in her book Empire in Retreat: The Story of India’s Partition (2012), labeled it as “hurried scuttle” of the British administration; Stanley Wolpert termed the British withdrawal as “shameful flight” in his insightful book Shameful Flight: The Last Years of the British Empire in India (2006); and Ilyas Chattha tried to gauge Partition’s impact on “locality” of Gujranwala and Sialkot in his treatise Partition and Locality: Violence, Migration, and Development in Gujranwala and Sialkot (2011).

The present book My Journey Home: Going Back to Lehnda Punjab is written by a person whose ancestors belonged to a small village of Butala Sardar Jhanda Singh, located in the vicinity of Gujranwala. Despite being one of the biggest landowning families of Gujranwala division, owning 42 jagirs owing to which their village was named as Butala or Butalia (forty-two in Punjabi language), Butalia family had to leave the area where it had lived for centuries.

Dr Tarunjit Singh Butalia used to listen to stories of violence and compassion from his grandmother who had herself experienced the trauma of the Partition of Punjab.

Butalia has brought Chardha (East) and Lehnda (West) Punjab closer by his optimistic and positive reflection of the events of Partition. He describes that when he asked his grandmother about her feelings for the person who did not let them carry important luggage when they had to leave Butala village, she was rather obliged and thankful to the Muslim who let them go safely. It is such an influence on him that Dr Butalia writes that, “for every partition story of human failings of horror and savagery, there is an even more compelling human story of compassion, love, and friendship at great personal peril.”

It was a Muslim family, according to Dr Butalia, who provided them protection and refuge for nearly a month in Lahore and then helped them cross the newly drawn border to Chardha Punjab where Dr Butalia was born in September 1965, the year of a full-scale war between post-colonial states of India and Pakistan. Dr Butalia’s father was at the warfront when he received the news of his birth. It signifies that Dr Butalia was born in an acute environment of, what he terms as, “patriotism of hate” against the rival country of Pakistan where roots of his both paternal and maternal ancestors belonged. Nonetheless, despite all this, Dr Butalia continued to reflect positively and optimistically about the relationship between India and Pakistan and decided to visit Lehnda Punjab.

The author has described his emotions of excitement and fear when he travelled from the United States of America to Pakistan. He narrates: “During my flight, my companions in the aircraft seats next to me were two young Pakistani boys who were excited to go home—I soon realized that I was also feeling like a young boy eagerly waiting to go home—but for the first time.”

On his way from the airport to Avari Hotel, the first sight that moved Dr Butalia was the Aitchison College located on the Mall Road where his father, grandfather, and great grandfather had studied. He reminisced “had it not been for the partition, I would also have most probably attended Aitchison College.” His friend Jahandad Khan took him to a Haveli called Harsukh (Peace for all)—owned by a retired Judge, Jawwad S. Khawaja (Ex-Chief Justice of Supreme Court of Pakistan)—where Mehboob Faridi, qawwals from Baba Farid’s shrine, performed. Dr Butalia’s family was given honorific title of Bhandari by Baba Farid himself and they were carrying this title along with the responsibility of making arrangements of langar (free meal) for nearly 750 years before leaving for Charhda Punjab. What gives a unique touch to the description and narration of this book is the poetry of Dr Butalia given invariably at the end of each chapter and that too concomitant with the themes discussed in that particular section.

The writer has described his experience of visiting various historical places located within the city of Lahore. The history of Lahore in the colonial times has quite recently received the attention of scholars like Ian Talbot and Tahir Kamran who produced a valuable treatise titled as Punjab in the Time of the Raj (2017). Lahore has remained a leading urban space and cultural center of Northern India. Moreover, it can rightly be termed as a cradle of religious diversity because it has monuments and historical places belonging to the Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs with nearly equal proportion. Dr Butalia has profusely praised places such as Badshahi Mosque, Lahore Fort, Gurdwara Dera Sahib, Mausoleum of Allama Iqbal, Rani Jindan Haveli, Princess Bamba Collection located in the Fort, Shaheedi Gurdwara, Gora Kabristan (Cemetery of the White), Wahga Border Parade, Zamzama Cannon, Shalimar Gardens, Shahi Hamam, Wazir Khan Mosque, Haveli Naunihal Singh, Anarkali’s Tomb, Lahore Museum, Aitchison College, and eateries of Gowalmandi.

However, the nostalgia of the author reached its zenith when he discovered a house in the interior streets of Lahore belonging to his maternal grandfather who was serving as a Railway Station Master in Lahore at the time of Partition of the Punjab. Dr Butalia saw his maternal grandfather’s name etched on a plaque: Sodhi Dilip Singh Son of Sodhi Kashmira Singh, July 1933. He rightly reiterated that “the red sandstone plaque waited for 72 years for someone to come claim it as its own.”

The place that Dr Butalia found as significant not only due to its Sufistic significance but also due to his family connection with this place was Baba Farid Dargah at Pakpattan. He visited the shrine of Baba Farid and listened to qawwali. Actually, a large number of verses called as Shaloks written by Baba Farid are part of Guru Garanth Sahb, the sacred book of Sikhism. A very important place visited by Butalia on his way back to Lahore was a building constructed during the time of Ranjit Singh as a shrine for famous syncretic Udasi Bhuman Shah. The center of shrine was profusely painted with Sikh era paintings. A painting that particularly caught attention of Dr Butalia was of a Sikh woman who was shown as riding a horse and playing lead hunter. He says that he had never seen a woman hunting in a painting and there was a glorious woman on horseback and hunting a deer. It signified equality of gender in Sikh faith. However, he felt saddened to think that the paintings that had survived for hundreds of years may not endure for long because of fast degradation of the building as well as paintings. He visited Baba Bulleh Shah’s shrine as well and having reached Lahore, once again, visited the home of his maternal family located at Ram Gali No. 7. Butalia’s love and longing for this place can well be understood because a glorious haveli had to be abandoned within hours and left for good, never to return to it again.

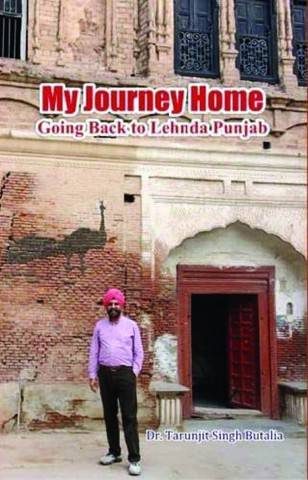

Dr Butalia’s last leg of the tour consisted of Gurdawara Darbar Sahib and then his long travel to North of Punjab including Taxila, Attock, and other places. However, the most significant was his visit to Butalia village (the picture on the jacket of the book) and the black peacock that still stands waiting for the dwellers of this graceful house. Butalia depicts this peacock and its longing for the owners of this house in one of his remarkable poems. His grandmother had told him about this black peacock while he was a child.

Besides its sentimental and emotional value, this book is a remarkable addition to the existing literature on Punjab and partition of Punjab. Dr Butalia has put in information along with the primary documents particularly his family pictures. Another outstanding feature of this book is its bilingualism. Dr Mazhar Abbas and Prof. Khizar Jawad have rendered a valuable service by translating it into maan boli (mother tongue) in Shahmukhi script. It not only expands its scope of readership but also connects its content with the cultural heritage of Punjab which can only be properly expressed in Punjabi. This book is a must read for students, scholars, historians, and especially for those who are interested in colonial and post-colonial Punjab. This book can be of immense interest for those who wish to relish-read the history and culture of Lahore in particular and Punjab in general.

The writer has a PhD in history from Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad and is Head of Department of History and Pakistan Studies at Sargodha University. He tweets @AbrarZahoor1

The present book My Journey Home: Going Back to Lehnda Punjab is written by a person whose ancestors belonged to a small village of Butala Sardar Jhanda Singh, located in the vicinity of Gujranwala. Despite being one of the biggest landowning families of Gujranwala division, owning 42 jagirs owing to which their village was named as Butala or Butalia (forty-two in Punjabi language), Butalia family had to leave the area where it had lived for centuries.

Dr Tarunjit Singh Butalia used to listen to stories of violence and compassion from his grandmother who had herself experienced the trauma of the Partition of Punjab.

Butalia has brought Chardha (East) and Lehnda (West) Punjab closer by his optimistic and positive reflection of the events of Partition. He describes that when he asked his grandmother about her feelings for the person who did not let them carry important luggage when they had to leave Butala village, she was rather obliged and thankful to the Muslim who let them go safely. It is such an influence on him that Dr Butalia writes that, “for every partition story of human failings of horror and savagery, there is an even more compelling human story of compassion, love, and friendship at great personal peril.”

It was a Muslim family, according to Dr Butalia, who provided them protection and refuge for nearly a month in Lahore and then helped them cross the newly drawn border to Chardha Punjab where Dr Butalia was born in September 1965, the year of a full-scale war between post-colonial states of India and Pakistan. Dr Butalia’s father was at the warfront when he received the news of his birth. It signifies that Dr Butalia was born in an acute environment of, what he terms as, “patriotism of hate” against the rival country of Pakistan where roots of his both paternal and maternal ancestors belonged. Nonetheless, despite all this, Dr Butalia continued to reflect positively and optimistically about the relationship between India and Pakistan and decided to visit Lehnda Punjab.

Besides its sentimental and emotional value, this book is a remarkable addition

to the existing literature on Punjab and the Partition

The author has described his emotions of excitement and fear when he travelled from the United States of America to Pakistan. He narrates: “During my flight, my companions in the aircraft seats next to me were two young Pakistani boys who were excited to go home—I soon realized that I was also feeling like a young boy eagerly waiting to go home—but for the first time.”

On his way from the airport to Avari Hotel, the first sight that moved Dr Butalia was the Aitchison College located on the Mall Road where his father, grandfather, and great grandfather had studied. He reminisced “had it not been for the partition, I would also have most probably attended Aitchison College.” His friend Jahandad Khan took him to a Haveli called Harsukh (Peace for all)—owned by a retired Judge, Jawwad S. Khawaja (Ex-Chief Justice of Supreme Court of Pakistan)—where Mehboob Faridi, qawwals from Baba Farid’s shrine, performed. Dr Butalia’s family was given honorific title of Bhandari by Baba Farid himself and they were carrying this title along with the responsibility of making arrangements of langar (free meal) for nearly 750 years before leaving for Charhda Punjab. What gives a unique touch to the description and narration of this book is the poetry of Dr Butalia given invariably at the end of each chapter and that too concomitant with the themes discussed in that particular section.

The writer has described his experience of visiting various historical places located within the city of Lahore. The history of Lahore in the colonial times has quite recently received the attention of scholars like Ian Talbot and Tahir Kamran who produced a valuable treatise titled as Punjab in the Time of the Raj (2017). Lahore has remained a leading urban space and cultural center of Northern India. Moreover, it can rightly be termed as a cradle of religious diversity because it has monuments and historical places belonging to the Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs with nearly equal proportion. Dr Butalia has profusely praised places such as Badshahi Mosque, Lahore Fort, Gurdwara Dera Sahib, Mausoleum of Allama Iqbal, Rani Jindan Haveli, Princess Bamba Collection located in the Fort, Shaheedi Gurdwara, Gora Kabristan (Cemetery of the White), Wahga Border Parade, Zamzama Cannon, Shalimar Gardens, Shahi Hamam, Wazir Khan Mosque, Haveli Naunihal Singh, Anarkali’s Tomb, Lahore Museum, Aitchison College, and eateries of Gowalmandi.

However, the nostalgia of the author reached its zenith when he discovered a house in the interior streets of Lahore belonging to his maternal grandfather who was serving as a Railway Station Master in Lahore at the time of Partition of the Punjab. Dr Butalia saw his maternal grandfather’s name etched on a plaque: Sodhi Dilip Singh Son of Sodhi Kashmira Singh, July 1933. He rightly reiterated that “the red sandstone plaque waited for 72 years for someone to come claim it as its own.”

The place that Dr Butalia found as significant not only due to its Sufistic significance but also due to his family connection with this place was Baba Farid Dargah at Pakpattan. He visited the shrine of Baba Farid and listened to qawwali. Actually, a large number of verses called as Shaloks written by Baba Farid are part of Guru Garanth Sahb, the sacred book of Sikhism. A very important place visited by Butalia on his way back to Lahore was a building constructed during the time of Ranjit Singh as a shrine for famous syncretic Udasi Bhuman Shah. The center of shrine was profusely painted with Sikh era paintings. A painting that particularly caught attention of Dr Butalia was of a Sikh woman who was shown as riding a horse and playing lead hunter. He says that he had never seen a woman hunting in a painting and there was a glorious woman on horseback and hunting a deer. It signified equality of gender in Sikh faith. However, he felt saddened to think that the paintings that had survived for hundreds of years may not endure for long because of fast degradation of the building as well as paintings. He visited Baba Bulleh Shah’s shrine as well and having reached Lahore, once again, visited the home of his maternal family located at Ram Gali No. 7. Butalia’s love and longing for this place can well be understood because a glorious haveli had to be abandoned within hours and left for good, never to return to it again.

Dr Butalia’s last leg of the tour consisted of Gurdawara Darbar Sahib and then his long travel to North of Punjab including Taxila, Attock, and other places. However, the most significant was his visit to Butalia village (the picture on the jacket of the book) and the black peacock that still stands waiting for the dwellers of this graceful house. Butalia depicts this peacock and its longing for the owners of this house in one of his remarkable poems. His grandmother had told him about this black peacock while he was a child.

Besides its sentimental and emotional value, this book is a remarkable addition to the existing literature on Punjab and partition of Punjab. Dr Butalia has put in information along with the primary documents particularly his family pictures. Another outstanding feature of this book is its bilingualism. Dr Mazhar Abbas and Prof. Khizar Jawad have rendered a valuable service by translating it into maan boli (mother tongue) in Shahmukhi script. It not only expands its scope of readership but also connects its content with the cultural heritage of Punjab which can only be properly expressed in Punjabi. This book is a must read for students, scholars, historians, and especially for those who are interested in colonial and post-colonial Punjab. This book can be of immense interest for those who wish to relish-read the history and culture of Lahore in particular and Punjab in general.

The writer has a PhD in history from Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad and is Head of Department of History and Pakistan Studies at Sargodha University. He tweets @AbrarZahoor1