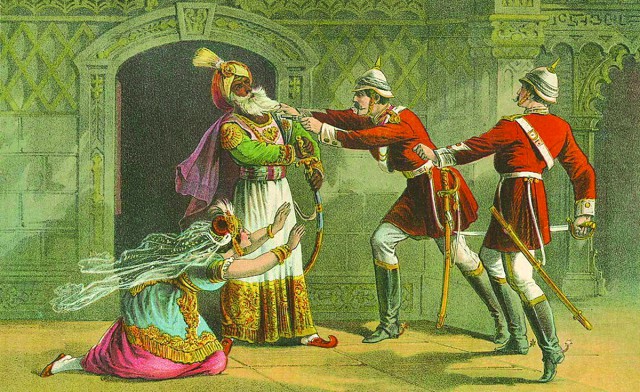

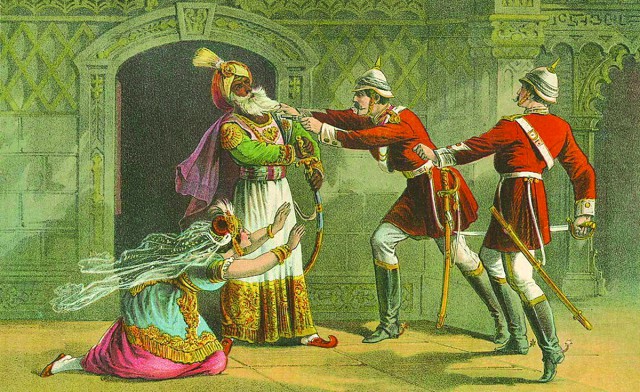

Almost one-and-half centuries have passed since the last Mughal emperor of India, Sirajuddin Mohammad Bahadur Shah Zafar, died in a state of utter poverty and destitution in Rangoon (Yangon), Burma (Myanmar). Now hailed as a sufi-saint, he had spent the last four years of his miserable life following his exile in 1858 from his ancestral capital, Delhi, as a British prisoner. He was the last member of the dynasty founded by Babur more than three centuries earlier that once ruled the richest and most powerful empire in the world.

Although countless books and articles, both in Urdu and English, have been written about the 1857 uprising, and Bahadur Shah Zafar and his pathetic 20-year long reign, a relatively recent book by the British author William Dalrymple, The Last Mughal, provides a well-research and detailed account of the Emperor, his powerlessness in the face of the uprising in 1857 and his subsequent exile to Rangoon. The former Emperor who used to live in the majestic Red Fort, with stately audience halls, Diwan-e-Khas and Aam in his use, was imprisoned with his family in a four-bedroom house to be watched round the clock by British superintendent Captain Nelson Davies. According to Davies, as cited by Dalrymple, two sentries guarded the prisoners during the day and three at night.

Meanwhile, the two grand audience chambers in Shah Jahan’s historic Red Fort were relegated to serve as the British officers’ mess. Gone were the days when meals were cooked and served to hundreds of extended family members all living in the Lal Qila. Now, the royal prisoners in their new dwellings were provided a lavish sum of 11 rupees per day for their meals, with Nelson Davies boasting that since he had taken over, an extra rupee had been added to their allowance on Sundays, and two rupees on the first day of every month. Their pathetic state is further illustrated by the following quote: “A supply of clothes has recently been provided, but their old stock being in a very dilapidated state, I shall presently be obliged to replenish it still further.”

Bahadur Shah Zafar, enfeebled with age-related infirmities, mixed with some degree of senility, spent most of his final days, “in listless apathy, manifesting considerable indifference to all but eternal affairs.” It would be inconceivable that any person who had endured so many tragedies and transformational changes within a few years would have fared any better. Bahadur Shah’s two young sons, the Mirzas Jawan Bakht and Shah Abbas, who were with him in captivity, received no formal education, except elementary reading and writing. They were entirely deprived of modern education.

Captain Davies, who had developed some empathy for the unfortunate family, wrote to the British authorities at Calcutta, the then capital, that the two princes be sent for education to England, where they might become more Anglophile. However, the Viceroy Lord Kennings’ office firmly rejected the proposal, even admonishing Davies not to refer to the captives as ex-King or ex-royals, instead they were to be addressed as the “Delhi state prisoners.”

The former Emperor survived in captivity for only four years. At age 87, on November 7, 1862, after a brief illness, he breathed his last, bringing to a close an unhappy and miserable chapter of his life. There was no large-scale mourning on his passing as great care was taken by the British that the news did not leak to the public. Bahadur Shah Zafar was buried quietly and unceremoniously in an unmarked grave in the presence of a few close family members. He had hoped to be laid to rest at Mehrauli, near Delhi, next to the shrine of Khawaja Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki, but that wish was not to be realized.

The grave had been kept purposefully unmarked and its location untraceable, lest it become a shrine, attracting pilgrims or devotees. However, following much agitation by Muslims in Rangoon, the British authorities agreed to erect a simple stone slab in 1907 with a gravestone identifying the site as that of the last Mughal Emperor. It all changed, however, when in 1991, during a dig for foundation of some unrelated building, the real grave of the former Emperor was discovered, and the body definitively identified that of him. A mausoleum was later constructed in 1994, which has now become a pilgrim site.

Paradoxically, as the Mughal Empire was going through its twilight years, Delhi saw a great florescence of fine arts, poetry and poetic gatherings, literature, painting, and social events. Zafar himself was a celebrated poet and calligrapher. Some of his poems expressing his anguish on his exile and depredation in a foreign land have become classics, among them the verse “Kitna hai badnaseeb Zafar, dafan key liye, do guzz zameen bhi mil na saki, kuye yaar main” which expresses his deep love and longing for his ancestral land.

Attempts have been made both on official and private levels in India to bring back the remains of the former Emperor home and to bury them at the site he so much desired. Both leaders of India and Pakistan have visited the grave site to offer respect and prayers. Indian President A.P.J, Abdul Kalam and Primes Minister Manmohan Singh came and paid tribute, while Presidents Musharraf and Asif Zardari visited the Mausoleum in 2001 and 2012 and offered Fatiha. Despite these high-level visits, not much progress has been made in bringing back the remains of the poet-Emperor to his motherland. Unfortunately, in the prevailing political situation in India and Myanmar, it is unlikely to happen anytime soon.

Bahadur Shah Zafar is perhaps one of the few Mughal emperors who are not maligned for being Muslims and foreign invaders. He is admired for being the face and symbol of resistance during the 1857 uprising against the British, when ordinary Indian sepoys, both Hindus and Muslims, acknowledged him as the rightful ruler of India and an emblem of their joint struggle. Their allegiance was largely token, as the Emperor had no real authority even in Delhi; the real authority was exercised by the British resident. Zafar followed the Sufi creed and set a personal example of tolerance, syncretism, and pluralism, considering himself the guardian of all his subjects. Hindu festivals, like Diwali and Dussehra, were officially celebrated at the court, just like Muslim festivals. In his book, Dalrymple mentions that Zafar enjoyed watching the annual Ram Lila procession that every year passed by the Red Fort. Hinduism, of course, was not the only creed that he honoured. He held great love for Hazrat Ali (AS), and in the month of Muharram, Majalis were held in the palace and the Emperor personally attended them.

Some fourteen Mughal rulers between Aurangzeb Alamgir and Bahadur Shah Zafar sat on the Delhi’s throne, a few reigning for only a few months or days. Almost all of them have been largely forgotten. However, the last emperor has left enduring footprints on the tapestry of Indian history, as a poet, as freedom fighter- albeit reluctant - and a proponent of communal harmony. He will not be forgotten.

Although countless books and articles, both in Urdu and English, have been written about the 1857 uprising, and Bahadur Shah Zafar and his pathetic 20-year long reign, a relatively recent book by the British author William Dalrymple, The Last Mughal, provides a well-research and detailed account of the Emperor, his powerlessness in the face of the uprising in 1857 and his subsequent exile to Rangoon. The former Emperor who used to live in the majestic Red Fort, with stately audience halls, Diwan-e-Khas and Aam in his use, was imprisoned with his family in a four-bedroom house to be watched round the clock by British superintendent Captain Nelson Davies. According to Davies, as cited by Dalrymple, two sentries guarded the prisoners during the day and three at night.

Meanwhile, the two grand audience chambers in Shah Jahan’s historic Red Fort were relegated to serve as the British officers’ mess. Gone were the days when meals were cooked and served to hundreds of extended family members all living in the Lal Qila. Now, the royal prisoners in their new dwellings were provided a lavish sum of 11 rupees per day for their meals, with Nelson Davies boasting that since he had taken over, an extra rupee had been added to their allowance on Sundays, and two rupees on the first day of every month. Their pathetic state is further illustrated by the following quote: “A supply of clothes has recently been provided, but their old stock being in a very dilapidated state, I shall presently be obliged to replenish it still further.”

Bahadur Shah Zafar, enfeebled with age-related infirmities, mixed with some degree of senility, spent most of his final days, “in listless apathy, manifesting considerable indifference to all but eternal affairs.” It would be inconceivable that any person who had endured so many tragedies and transformational changes within a few years would have fared any better. Bahadur Shah’s two young sons, the Mirzas Jawan Bakht and Shah Abbas, who were with him in captivity, received no formal education, except elementary reading and writing. They were entirely deprived of modern education.

Captain Davies, who had developed some empathy for the unfortunate family, wrote to the British authorities at Calcutta, the then capital, that the two princes be sent for education to England, where they might become more Anglophile. However, the Viceroy Lord Kennings’ office firmly rejected the proposal, even admonishing Davies not to refer to the captives as ex-King or ex-royals, instead they were to be addressed as the “Delhi state prisoners.”

The former Emperor survived in captivity for only four years. At age 87, on November 7, 1862, after a brief illness, he breathed his last, bringing to a close an unhappy and miserable chapter of his life. There was no large-scale mourning on his passing as great care was taken by the British that the news did not leak to the public. Bahadur Shah Zafar was buried quietly and unceremoniously in an unmarked grave in the presence of a few close family members. He had hoped to be laid to rest at Mehrauli, near Delhi, next to the shrine of Khawaja Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki, but that wish was not to be realized.

The grave had been kept purposefully unmarked and its location untraceable, lest it become a shrine, attracting pilgrims or devotees. However, following much agitation by Muslims in Rangoon, the British authorities agreed to erect a simple stone slab in 1907 with a gravestone identifying the site as that of the last Mughal Emperor. It all changed, however, when in 1991, during a dig for foundation of some unrelated building, the real grave of the former Emperor was discovered, and the body definitively identified that of him. A mausoleum was later constructed in 1994, which has now become a pilgrim site.

Paradoxically, as the Mughal Empire was going through its twilight years, Delhi saw a great florescence of fine arts, poetry and poetic gatherings, literature, painting, and social events. Zafar himself was a celebrated poet and calligrapher. Some of his poems expressing his anguish on his exile and depredation in a foreign land have become classics, among them the verse “Kitna hai badnaseeb Zafar, dafan key liye, do guzz zameen bhi mil na saki, kuye yaar main” which expresses his deep love and longing for his ancestral land.

Attempts have been made both on official and private levels in India to bring back the remains of the former Emperor home and to bury them at the site he so much desired. Both leaders of India and Pakistan have visited the grave site to offer respect and prayers. Indian President A.P.J, Abdul Kalam and Primes Minister Manmohan Singh came and paid tribute, while Presidents Musharraf and Asif Zardari visited the Mausoleum in 2001 and 2012 and offered Fatiha. Despite these high-level visits, not much progress has been made in bringing back the remains of the poet-Emperor to his motherland. Unfortunately, in the prevailing political situation in India and Myanmar, it is unlikely to happen anytime soon.

Bahadur Shah Zafar is perhaps one of the few Mughal emperors who are not maligned for being Muslims and foreign invaders. He is admired for being the face and symbol of resistance during the 1857 uprising against the British, when ordinary Indian sepoys, both Hindus and Muslims, acknowledged him as the rightful ruler of India and an emblem of their joint struggle. Their allegiance was largely token, as the Emperor had no real authority even in Delhi; the real authority was exercised by the British resident. Zafar followed the Sufi creed and set a personal example of tolerance, syncretism, and pluralism, considering himself the guardian of all his subjects. Hindu festivals, like Diwali and Dussehra, were officially celebrated at the court, just like Muslim festivals. In his book, Dalrymple mentions that Zafar enjoyed watching the annual Ram Lila procession that every year passed by the Red Fort. Hinduism, of course, was not the only creed that he honoured. He held great love for Hazrat Ali (AS), and in the month of Muharram, Majalis were held in the palace and the Emperor personally attended them.

Some fourteen Mughal rulers between Aurangzeb Alamgir and Bahadur Shah Zafar sat on the Delhi’s throne, a few reigning for only a few months or days. Almost all of them have been largely forgotten. However, the last emperor has left enduring footprints on the tapestry of Indian history, as a poet, as freedom fighter- albeit reluctant - and a proponent of communal harmony. He will not be forgotten.