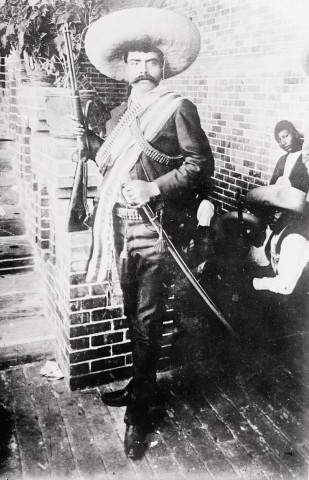

This photograph shows Emiliano Zapata, posing in Cuernavaca in 1911, with a rifle and sword, and a ceremonial sash across his chest.

Emiliano Zapata Salazar became a leading figure in the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1920, the main leader of the peasant revolution in the Mexican state of Morelos, and the inspiration of the agrarian movement called Zapatismo.

Zapata was born in the rural village of Anenecuilco in Morelos State, in an era when peasant communities came under increasing pressure from the small-landowning class who monopolized land and water resources for sugar-cane production with the support of dictator Porfirio Díaz (president 1877-1880 and 1884-1911).

Zapata early on participated in political movements against Díaz and the landowning hacendados, and when the Revolution broke out in 1910, he was thus positioned as a central leader of the peasant revolt in Morelos. Cooperating with a number of other peasant leaders, he formed the Liberation Army of the South, of which he soon became the undisputed leader. Zapata’s forces contributed to the fall of Díaz, defeating the Federal Army in the Battle of Cuautla (May 1911), but when the revolutionary leader Francisco I. Madero became President, he disavowed the role of the Zapatistas, denouncing them as simple bandits. In November 1911, Zapata promulgated the Plan de Ayala, which called for substantial land reforms, redistributing lands to the peasants. Madero sent the Federal Army to root out the Zapatistas in Morelos. Madero’s generals employed a scorched-earth policy, burning villages and forcibly removing their inhabitants and drafting many men into the army or sending them to forced-labor camps in southern Mexico.

Such actions strengthened Zapata’s standing among the peasants, and Zapata succeeded in driving the forces of Madero (led by Victoriano Huerta) out of Morelos. In a coup against Madero in February 1913, Huerta took power in Mexico, but a coalition of Constitutionalist forces in northern Mexico led by Venustiano Carranza, Álvaro Obregón and Francisco “Pancho” Villa ousted him in July 1914 with the support of Zapata’s troops.

Zapata did not recognize the authority that Carranza asserted as leader of the revolutionary movement, continuing his adherence to the Plan de Ayala.

In the aftermath of the revolutionaries’ victory over Huerta, they attempted to sort out power relations in the Convention of Aguascalientes (October to November 1914). Zapata and Villa broke with Carranza, and Mexico descended into a civil war among the winners. Dismayed with the alliance with Villa, Zapata focused his energies on rebuilding society in Morelos (which he now controlled), instituting the land reforms of the Plan de Ayala. As Carranza consolidated his power and defeated Villa in 1915, Zapata initiated guerrilla warfare against the Carrancistas, who in turn invaded Morelos, employing once again scorched-earth tactics to oust the Zapatista rebels. Zapata once again re-took Morelos in 1917 and held most of the state against Carranza’s troops until he was killed in an ambush in April 1919.

Article 27 of the 1917 Mexican Constitution was drafted in response to Zapata’s agrarian demands.

After his death, Zapatista generals aligned with Obregón against Carranza and helped drive Carranza from power (1920). In 1920 Zapatistas managed to obtain powerful posts in the government of Morelos after Carranza’s fall. They instituted many of the land reforms envisioned by Zapata in Morelos.

Zapata remains an iconic figure in Mexico, used both as a nationalist symbol as well as a symbol of the neo-Zapatista movement.

Emiliano Zapata Salazar became a leading figure in the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1920, the main leader of the peasant revolution in the Mexican state of Morelos, and the inspiration of the agrarian movement called Zapatismo.

Zapata was born in the rural village of Anenecuilco in Morelos State, in an era when peasant communities came under increasing pressure from the small-landowning class who monopolized land and water resources for sugar-cane production with the support of dictator Porfirio Díaz (president 1877-1880 and 1884-1911).

Zapata early on participated in political movements against Díaz and the landowning hacendados, and when the Revolution broke out in 1910, he was thus positioned as a central leader of the peasant revolt in Morelos. Cooperating with a number of other peasant leaders, he formed the Liberation Army of the South, of which he soon became the undisputed leader. Zapata’s forces contributed to the fall of Díaz, defeating the Federal Army in the Battle of Cuautla (May 1911), but when the revolutionary leader Francisco I. Madero became President, he disavowed the role of the Zapatistas, denouncing them as simple bandits. In November 1911, Zapata promulgated the Plan de Ayala, which called for substantial land reforms, redistributing lands to the peasants. Madero sent the Federal Army to root out the Zapatistas in Morelos. Madero’s generals employed a scorched-earth policy, burning villages and forcibly removing their inhabitants and drafting many men into the army or sending them to forced-labor camps in southern Mexico.

Such actions strengthened Zapata’s standing among the peasants, and Zapata succeeded in driving the forces of Madero (led by Victoriano Huerta) out of Morelos. In a coup against Madero in February 1913, Huerta took power in Mexico, but a coalition of Constitutionalist forces in northern Mexico led by Venustiano Carranza, Álvaro Obregón and Francisco “Pancho” Villa ousted him in July 1914 with the support of Zapata’s troops.

Zapata did not recognize the authority that Carranza asserted as leader of the revolutionary movement, continuing his adherence to the Plan de Ayala.

In the aftermath of the revolutionaries’ victory over Huerta, they attempted to sort out power relations in the Convention of Aguascalientes (October to November 1914). Zapata and Villa broke with Carranza, and Mexico descended into a civil war among the winners. Dismayed with the alliance with Villa, Zapata focused his energies on rebuilding society in Morelos (which he now controlled), instituting the land reforms of the Plan de Ayala. As Carranza consolidated his power and defeated Villa in 1915, Zapata initiated guerrilla warfare against the Carrancistas, who in turn invaded Morelos, employing once again scorched-earth tactics to oust the Zapatista rebels. Zapata once again re-took Morelos in 1917 and held most of the state against Carranza’s troops until he was killed in an ambush in April 1919.

Article 27 of the 1917 Mexican Constitution was drafted in response to Zapata’s agrarian demands.

After his death, Zapatista generals aligned with Obregón against Carranza and helped drive Carranza from power (1920). In 1920 Zapatistas managed to obtain powerful posts in the government of Morelos after Carranza’s fall. They instituted many of the land reforms envisioned by Zapata in Morelos.

Zapata remains an iconic figure in Mexico, used both as a nationalist symbol as well as a symbol of the neo-Zapatista movement.