I have been trying to explain the practical use of mathematics to my sixteen-year-old daughter, with little success.

For some time now, I have thought it is necessary to explain to her as to why a subject is important: why we are taught things at school that we may never use afterwards, etc. It has been easier process to explain languages (to communicate), the arts (they help you express yourself) and history (for those who forget history are condemned to relive it). Why is it that the theory of maths is never taught like other subjects?

Little did I realise that Islamic geometrical patterns would come in handy at this point. One has only to visit an old architecturally inspiring building to see how intricate patterns could be created by master craftsmen who may have been functionally illiterate but had extensive and detailed knowledge of practical geometry. They began with a circle which would be divided into sections, equally. And then the basic motifs would be replicated in uniformity to create a perfect whole.

I decided to explore what mastering a basic geometrical technique would mean in this digital age. One needed only a compass and a ruler - the same as those used in 300 AC by the Greek mathematician Euclid.

Patterns are useful in that they create habits in real life but in architecture and design, they are essential. A single motif, whether a floral leaf pattern or the “khamsa” (the five-fingered hand) would be replicated repeatedly to fill an entire wall. A basic building block was of six sides or the basic hexagon based on a circle – a perfect symbol of true symmetry. The straight lines may be 5 just line drawings but what elevates this to art is the use of different elements and shape, whether flowers or leaves enhanced by colour to achieve harmony and balance.

Many years ago, in 2008, I was privileged to visit the grand mosque in Damascus in Syria. I was working on an Aga Khan-related project at the time. It was engaged with trying to transform their rural support program into a licensed microfinance Bank. As with most privileges in life, you realise how lucky you were only afterwards. One of the most beautiful aspects of that week was to walk through the ancient city of Damascus and to witness the amazing efforts by the Aga Khan network to restore the old city.

Damascus, along with Jerusalem and Madinah, is one of the most important cities of the Islamic empire. The mosque there dates back to the 8th century. It was built by the ambitious Umayyad Caliph Al Walid. Though much of the original decorations have been destroyed, the interior still contains a series of mosaics using repetitive patterns – a series of stars and cubes repeated in perfect symmetry. Aside from the mosaics, the grounds house a shrine reputedly holding the remains of John the Baptist and the tomb of Salahuddin al-Ayyubi dating back to the 12th century.

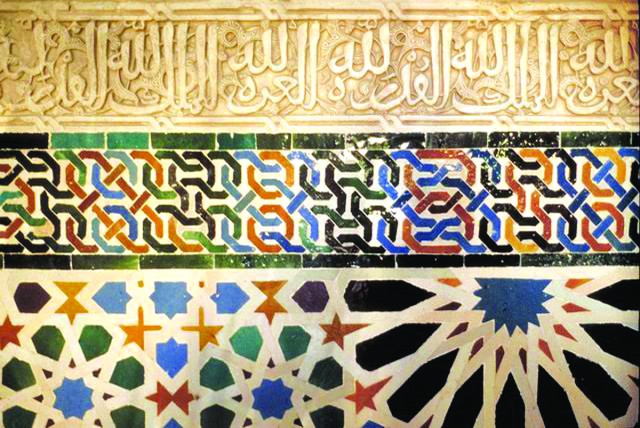

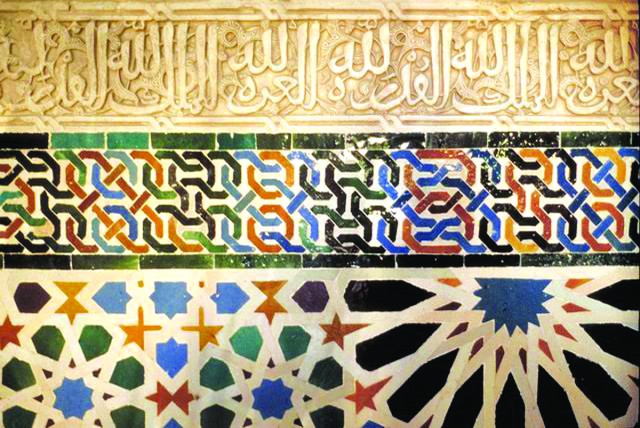

Another fine example of this is Al-Hamra in Spain or the grand mosque of Cordoba. Upon visiting each, I was struck by the parallels between our local mosques and the design influences that subconsciously pervaded history. The complex comprises a series of palaces, mansions, courtyards which house its renowned tile patterns whether in the wooden ceilings or carvings in stucco. Again the use of floral motifs enhanced the geometric patterns.

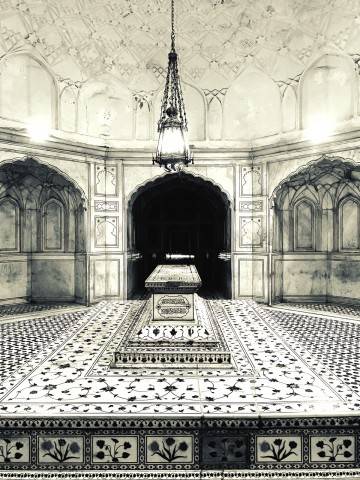

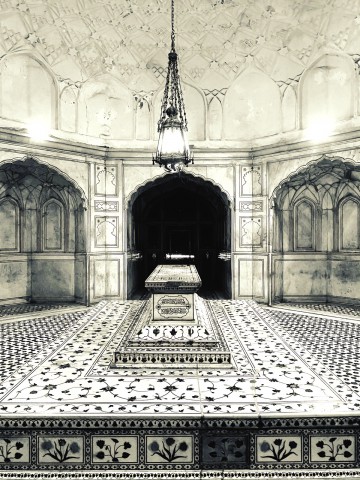

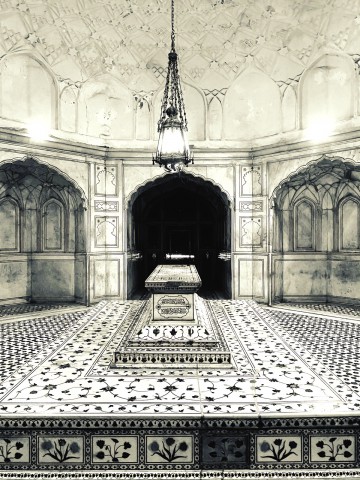

Closer to home, in Pakistan, many Sufi shrines provide such imagery – relying on the use of glazed tiles and repetitive patterns whether in Bibi Jawandi’s shrine in Uchh Sharif or the patterns in Mughal-era architecture in Lahore, such as the Wazir Khan mosque or the emperor Jahangir’s mausoleum. As for the latter, built as it was in the outskirts of our hometown Lahore, it was often the place I used to love to escape to as a teenager. The gardens were otherworldly – one could disappear into magic gardens of old gnarled banyans and mango trees. We used to picnic there, often on shami kebabs and egg sandwiches. As a treat, we were allowed to climb up to the top of the minarets. That privilege is no longer available to visitors today.

Even now I often wonder what secrets the pietra dura walls keep and what the birds chatter about after spending their day nesting in such a magnificent landscape. It is a place of retreat, designed for reflection and remains a refuge even four hundred years later. There is a comforting sense of peace as one walks through its gardens. The Persian-inspired architecture was likely influenced by Nur Jehan’s background and design aesthetic. My favorite enduring recollection of this are the marble jalis or lattices, designed in spiritual symmetry, with light flowing through from all four sides.

The gardens themselves are designed on a geometrical scheme, again their aesthetic based on a Persian Chahar-bagh or the garden of Paradise – with walk ways separated by channels to reflect the different paths to paradise.

So as I trace my patterns and imagine the road to Jannat or paradise, I come back to the real world to teach the art of maths. For who can imagine a better road to paradise than through drawing a series of hexagons and perfect squares in repetitive order? Understanding patterns, or mathematics, is akin to understanding the meaning of life and the circular road to Paradise!

For some time now, I have thought it is necessary to explain to her as to why a subject is important: why we are taught things at school that we may never use afterwards, etc. It has been easier process to explain languages (to communicate), the arts (they help you express yourself) and history (for those who forget history are condemned to relive it). Why is it that the theory of maths is never taught like other subjects?

Little did I realise that Islamic geometrical patterns would come in handy at this point. One has only to visit an old architecturally inspiring building to see how intricate patterns could be created by master craftsmen who may have been functionally illiterate but had extensive and detailed knowledge of practical geometry. They began with a circle which would be divided into sections, equally. And then the basic motifs would be replicated in uniformity to create a perfect whole.

I decided to explore what mastering a basic geometrical technique would mean in this digital age. One needed only a compass and a ruler - the same as those used in 300 AC by the Greek mathematician Euclid.

Patterns are useful in that they create habits in real life but in architecture and design, they are essential. A single motif, whether a floral leaf pattern or the “khamsa” (the five-fingered hand) would be replicated repeatedly to fill an entire wall. A basic building block was of six sides or the basic hexagon based on a circle – a perfect symbol of true symmetry. The straight lines may be 5 just line drawings but what elevates this to art is the use of different elements and shape, whether flowers or leaves enhanced by colour to achieve harmony and balance.

Many years ago, in 2008, I was privileged to visit the grand mosque in Damascus in Syria. I was working on an Aga Khan-related project at the time. It was engaged with trying to transform their rural support program into a licensed microfinance Bank. As with most privileges in life, you realise how lucky you were only afterwards. One of the most beautiful aspects of that week was to walk through the ancient city of Damascus and to witness the amazing efforts by the Aga Khan network to restore the old city.

Damascus, along with Jerusalem and Madinah, is one of the most important cities of the Islamic empire. The mosque there dates back to the 8th century. It was built by the ambitious Umayyad Caliph Al Walid. Though much of the original decorations have been destroyed, the interior still contains a series of mosaics using repetitive patterns – a series of stars and cubes repeated in perfect symmetry. Aside from the mosaics, the grounds house a shrine reputedly holding the remains of John the Baptist and the tomb of Salahuddin al-Ayyubi dating back to the 12th century.

Another fine example of this is Al-Hamra in Spain or the grand mosque of Cordoba. Upon visiting each, I was struck by the parallels between our local mosques and the design influences that subconsciously pervaded history. The complex comprises a series of palaces, mansions, courtyards which house its renowned tile patterns whether in the wooden ceilings or carvings in stucco. Again the use of floral motifs enhanced the geometric patterns.

Closer to home, in Pakistan, many Sufi shrines provide such imagery – relying on the use of glazed tiles and repetitive patterns whether in Bibi Jawandi’s shrine in Uchh Sharif or the patterns in Mughal-era architecture in Lahore, such as the Wazir Khan mosque or the emperor Jahangir’s mausoleum. As for the latter, built as it was in the outskirts of our hometown Lahore, it was often the place I used to love to escape to as a teenager. The gardens were otherworldly – one could disappear into magic gardens of old gnarled banyans and mango trees. We used to picnic there, often on shami kebabs and egg sandwiches. As a treat, we were allowed to climb up to the top of the minarets. That privilege is no longer available to visitors today.

Even now I often wonder what secrets the pietra dura walls keep and what the birds chatter about after spending their day nesting in such a magnificent landscape. It is a place of retreat, designed for reflection and remains a refuge even four hundred years later. There is a comforting sense of peace as one walks through its gardens. The Persian-inspired architecture was likely influenced by Nur Jehan’s background and design aesthetic. My favorite enduring recollection of this are the marble jalis or lattices, designed in spiritual symmetry, with light flowing through from all four sides.

The gardens themselves are designed on a geometrical scheme, again their aesthetic based on a Persian Chahar-bagh or the garden of Paradise – with walk ways separated by channels to reflect the different paths to paradise.

So as I trace my patterns and imagine the road to Jannat or paradise, I come back to the real world to teach the art of maths. For who can imagine a better road to paradise than through drawing a series of hexagons and perfect squares in repetitive order? Understanding patterns, or mathematics, is akin to understanding the meaning of life and the circular road to Paradise!