It is important to sow seeds for the future. During COVID imposed lockdowns and restrictions, it has been difficult for many to rise and shine. None of us is immune. A recent survey conducted in Washington DC reported that if one used Harvard’s School of Public health categorization, then almost 60% of the data pool where I work are suffering from anxiety and mild depression. From a sample pool of millions spread globally, the numbers speak for themselves. People are suffering in different ways – financial and emotional distress, managing in conditions fraught with uncertainty, insomnia and anxiety.

This has become apparent in the deterioration in social relationships, an inability to concentrate, lack of self-control, irrational aggression, even negative coping mechanisms that lead to escapist drinking and drugs. Mental health issues have come out of the closet. They are being acknowledged and spoken about more openly than ever before. But the Covid-19 pandemic is not the only one we should blame. We must look within ourselves and how we can cultivate resilience on a daily basis.

In that regard we have a lot to learn from Japan and the concept of zen. I chanced upon a Japanese documentary recently about a young auto mechanic Takayuki who farms on the weekend in Hiroshima. He has been doing a Youtube channel on agricultural practices at the weekend. This became popular and particularly with the youth in Japan. One group of children flocked to his farm to learn about how to restore their school garden and he began to host workshops at the farm to share farming techniques.

Clearly, going back to nature is primeval. Our ancestors used to forage for fruits, nuts and seeds, I like to imagine that mine would be mixing evocative spices into their edible baskets, perhaps in the form of saffron or mulberry herbs. There is much evidence to suggest that spending time in nature reduces one’s stress levels. It has been scientifically proven that exposure to nature reduces anger, stress and fear. It contributes imperceptibly to physical wellbeing by reducing muscle tension and the production of stress hormones. This can achieved by simply strolling in the woods (the Japanese even have a name for it – Shinrin yoku literally translated as forest bathing) and engaging with the natural world through our senses.

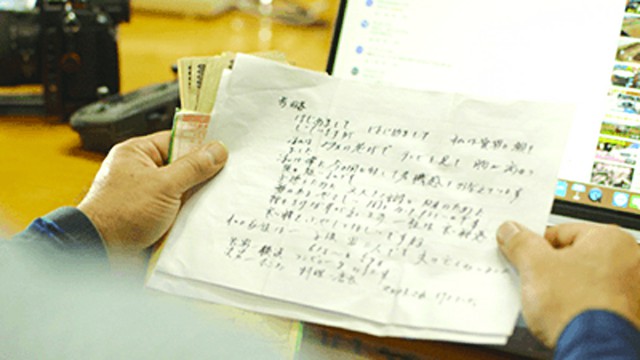

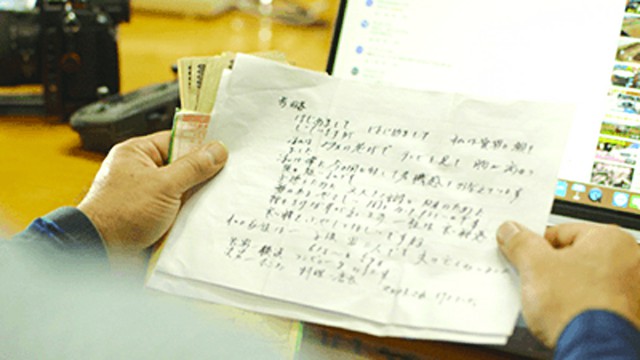

The story of young Takayuki is compelling as his need to move from modern machinery back to the earth shows the human need to restore one’s spirit. His Youtube channel became increasingly popular in Japan with more than 50,000 subscribers. One day, out of the blue, he received 100,000 yen (about a US$1000) and a letter from an old lady. The 86-year-old elderly woman Shige lives a solitary existence in Mie. Like many of us, she watches way too much TV for her own good. She was struck by Takuhushi’s endeavors and his commitment to creating a better Japan. In May 2020, she decided to channel her COVID 19 special cash payment – provided by the Japanese government to help those affected – to this young stranger.

The etiquette of gift giving is inextricably linked to Japanese culture. In Kyoto people exchange gifts when seasons change and has its origins in ancient court ceremonies that express gratitude and celebration. For instance, a newborn girl in her first year receives dolls to mark the emperor and the empress. People exchange Senmazuike turnip pickles at the year’s end (the Japanese equivalent of Pakistani summer-time mango exchanges). These in turn help build the culture of maintaining relationships and recognizing others.

The story of Shige and Takayuki is touching in a special way. Shige wants this young man to share the joy of raising vegetables to a broader audience. The young amateur farmer is struck by her generosity and decides that the best legacy is not to spend money on farm equipment or working capital but to sow more seeds. This is the most important part of crop production – of planting the seeds in soil, for a future harvest.

The effect of sowing seeds is not a recent phenomenon. Several Biblical references exist along the lines that if one sows sparingly then life is sparing or if one sows in bounty, it can create a bountiful life. This was echoed in different religions – whether Christianity or Buddhism and across the world whether through religion or poetry. Thoughts and words are often interconnected with seeds. Wordsworth poetically linked bad thoughts to weeds and thoughts and words planted with care to blooming flowers.

In a way, there is magic in seeing nature grow out of itself. An acorn becomes a mighty oak. A tendril becomes a bunch of grapes. The Japanese concept of zen is intimately linked with nature. Zen is often ascribed to meditative practices and restraint but it is equally applicable to physical cultivation or the nature of physical things. And what could be more meditative than leaving the world of machines in an auto repair shop at the end of the week and then communing with fields of vegetables and exotic green plants? A Japanese farm is more than a place of produce; it becomes a calming sanctuary of elegantly proportioned Japanese vegetables.

This weekend I attended a Zoom funeral for a family friend’s parent. The deceased was an Indian army officer’s wife whose value system was very much caught up with excellence and military-like discipline. Hearing her tribute was almost like hearing about my own grandmother – also an army officer’s wife – who lived a remarkably parallel existence on the other side of the border during the 1950s.

One of her sons remarked on her passions – the three Cs – cards, chai and cricket as well as her commitment to perfection on the home front: making beds to hotel-like quality within minutes of waking, a sparkling clean house devoid of clutter and a warm way with others. One nephew remarked that she always remembered birthdays – calling at 9 am without fail each year – and maintained a social protocol until she died. Those who remember her fondly remember her affection for them, her acts of service, her time for others, her ability to see them for who they were and how she touched people –whether her grandson and his friends in thinly veiled maths lessons during play dates or driving her own sons to strive for academic excellence. These words resound in my mind –excellence, discipline, empathy and one’s s search for all of the above. These may not come naturally to us each day, but we must strive for them. I think back to Shige and her selfless gift. Through it, she engaged with the soil of her own country, the very soil that made her.

As a result of this documentary, I was ready to jump onto the next plane to Japan and to ride out the rest of COVID in rural surroundings. It would be nice to grow beautifully proportioned cucumbers and celery, or even better to run my chaotic household like a Navy Seal. It is only when I speak to Japanese friends that I realize they suffer the same mental anxiety that all of us do. Similarly, my friends remind me that that even within other households, commitment to excellence can be a difficult thing to maintain day after day.

The answer perhaps lies in Takayuki’s way - one day at a time, one weekend at a time. One has to sow the seeds of time, attend to them, give them light and space to grow, and then be patient. Only then one can reap the harvest of a tastier tomorrow.

This has become apparent in the deterioration in social relationships, an inability to concentrate, lack of self-control, irrational aggression, even negative coping mechanisms that lead to escapist drinking and drugs. Mental health issues have come out of the closet. They are being acknowledged and spoken about more openly than ever before. But the Covid-19 pandemic is not the only one we should blame. We must look within ourselves and how we can cultivate resilience on a daily basis.

In that regard we have a lot to learn from Japan and the concept of zen. I chanced upon a Japanese documentary recently about a young auto mechanic Takayuki who farms on the weekend in Hiroshima. He has been doing a Youtube channel on agricultural practices at the weekend. This became popular and particularly with the youth in Japan. One group of children flocked to his farm to learn about how to restore their school garden and he began to host workshops at the farm to share farming techniques.

Clearly, going back to nature is primeval. Our ancestors used to forage for fruits, nuts and seeds, I like to imagine that mine would be mixing evocative spices into their edible baskets, perhaps in the form of saffron or mulberry herbs. There is much evidence to suggest that spending time in nature reduces one’s stress levels. It has been scientifically proven that exposure to nature reduces anger, stress and fear. It contributes imperceptibly to physical wellbeing by reducing muscle tension and the production of stress hormones. This can achieved by simply strolling in the woods (the Japanese even have a name for it – Shinrin yoku literally translated as forest bathing) and engaging with the natural world through our senses.

The story of young Takayuki is compelling as his need to move from modern machinery back to the earth shows the human need to restore one’s spirit. His Youtube channel became increasingly popular in Japan with more than 50,000 subscribers. One day, out of the blue, he received 100,000 yen (about a US$1000) and a letter from an old lady. The 86-year-old elderly woman Shige lives a solitary existence in Mie. Like many of us, she watches way too much TV for her own good. She was struck by Takuhushi’s endeavors and his commitment to creating a better Japan. In May 2020, she decided to channel her COVID 19 special cash payment – provided by the Japanese government to help those affected – to this young stranger.

People exchange Senmazuike turnip pickles at the year’s end (the Japanese equivalent of Pakistani summer-time mango exchanges)

The etiquette of gift giving is inextricably linked to Japanese culture. In Kyoto people exchange gifts when seasons change and has its origins in ancient court ceremonies that express gratitude and celebration. For instance, a newborn girl in her first year receives dolls to mark the emperor and the empress. People exchange Senmazuike turnip pickles at the year’s end (the Japanese equivalent of Pakistani summer-time mango exchanges). These in turn help build the culture of maintaining relationships and recognizing others.

The story of Shige and Takayuki is touching in a special way. Shige wants this young man to share the joy of raising vegetables to a broader audience. The young amateur farmer is struck by her generosity and decides that the best legacy is not to spend money on farm equipment or working capital but to sow more seeds. This is the most important part of crop production – of planting the seeds in soil, for a future harvest.

The effect of sowing seeds is not a recent phenomenon. Several Biblical references exist along the lines that if one sows sparingly then life is sparing or if one sows in bounty, it can create a bountiful life. This was echoed in different religions – whether Christianity or Buddhism and across the world whether through religion or poetry. Thoughts and words are often interconnected with seeds. Wordsworth poetically linked bad thoughts to weeds and thoughts and words planted with care to blooming flowers.

In a way, there is magic in seeing nature grow out of itself. An acorn becomes a mighty oak. A tendril becomes a bunch of grapes. The Japanese concept of zen is intimately linked with nature. Zen is often ascribed to meditative practices and restraint but it is equally applicable to physical cultivation or the nature of physical things. And what could be more meditative than leaving the world of machines in an auto repair shop at the end of the week and then communing with fields of vegetables and exotic green plants? A Japanese farm is more than a place of produce; it becomes a calming sanctuary of elegantly proportioned Japanese vegetables.

This weekend I attended a Zoom funeral for a family friend’s parent. The deceased was an Indian army officer’s wife whose value system was very much caught up with excellence and military-like discipline. Hearing her tribute was almost like hearing about my own grandmother – also an army officer’s wife – who lived a remarkably parallel existence on the other side of the border during the 1950s.

One of her sons remarked on her passions – the three Cs – cards, chai and cricket as well as her commitment to perfection on the home front: making beds to hotel-like quality within minutes of waking, a sparkling clean house devoid of clutter and a warm way with others. One nephew remarked that she always remembered birthdays – calling at 9 am without fail each year – and maintained a social protocol until she died. Those who remember her fondly remember her affection for them, her acts of service, her time for others, her ability to see them for who they were and how she touched people –whether her grandson and his friends in thinly veiled maths lessons during play dates or driving her own sons to strive for academic excellence. These words resound in my mind –excellence, discipline, empathy and one’s s search for all of the above. These may not come naturally to us each day, but we must strive for them. I think back to Shige and her selfless gift. Through it, she engaged with the soil of her own country, the very soil that made her.

As a result of this documentary, I was ready to jump onto the next plane to Japan and to ride out the rest of COVID in rural surroundings. It would be nice to grow beautifully proportioned cucumbers and celery, or even better to run my chaotic household like a Navy Seal. It is only when I speak to Japanese friends that I realize they suffer the same mental anxiety that all of us do. Similarly, my friends remind me that that even within other households, commitment to excellence can be a difficult thing to maintain day after day.

The answer perhaps lies in Takayuki’s way - one day at a time, one weekend at a time. One has to sow the seeds of time, attend to them, give them light and space to grow, and then be patient. Only then one can reap the harvest of a tastier tomorrow.