In today’s dizzying world, one that pulsates with promises of change, there is still a gap between drawing room discussions and real actions; there is still a divide between the people who talk the talk and those who walk the talk.

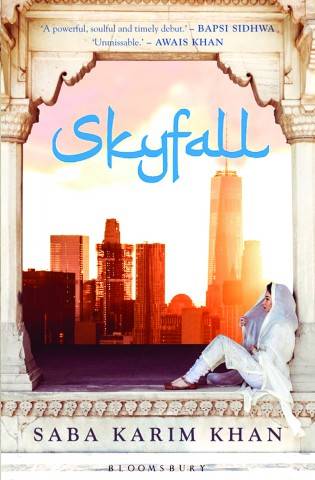

It is exactly this haunting hypocrisy that Saba Karim Khan brilliantly identifies and beautifully pens in her debut novel, Skyfall. Khan does not have an easy task at hand, she plays with a plot and in it, themes and characters that are destined against all odds to fail - to fail at existing, to fail at living and even more so to fail at achieving justice of any kind.

It is as if she already knows this disconnected dilemma and thus, writes her prose ever so vividly, descriptively detailed, and poignantly versed, immediately immersing the reader into the chilling world of the unseen, unknown and inexperienced. The minute one picks this book, they are invited into the alleyways, quaint streets, pan shops, even the potholes, distinct aroma, distant music, and dance – they become part of the taboo, part of the secret, part of a select few the story chooses to confide in.

The hushed business of Heera Mandi, Lahore’s red-light district is broken down, and the reader becomes privy to it all, through its characters and the intimate, secret diary writing style that Khan crafts throughout the novel.

Skyfall reminds me of a novel I read years ago, called Shame by Salman Rushdie which plays with themes of shame, the sobriquet of its passive heroine who absorbs the shame around her, much like Khan’s main character, Rania. Both Rushdie’s ‘Shame’ and Khan’s ‘Skyfall’, speak not only of an individual’s shame but also society which gives shame an undue important and central place in their lives. Both novels also explore the interplay of disparate societies and the great chasms they present: the powerful and moneyed versus the poor and powerless, the educated and elite versus the so called uneducated and unenlightened and the question of mortality – right versus wrong. A particular verse from Rushdie’s Shame resonated with me after I finished Khan’s Skyfall: “Shame is like everything else; live with it long enough and it becomes part of the furniture. Between shame and shamelessness lies the axis upon which we turn; meteorological conditions at both these poles are of the most extreme, ferocious type. Shamelessness, shame; the roots of violence.”

Rushdie and Khan both through their novels intrinsically propel a reader to question how arbitrary shame is, by openly questioning and exploring what shame really is and how massive the impact of its pretence can be if not dealt with. How on one hand when one lives with it, one can get complacent to act against it, but on the other hand, when one does act against and achieves justice for a larger majority, it can be liberating – the choice is but ours.

Khan’s Skyfall is a tale of painful dichotomy, a world with a clear good and evil, but in a typecast setting, where we know which will reign and win – it is always those with the money, power and connections that do – not the faceless, shunned population she chooses as her characters. Khan posits the latter as the real heroes of our world, and it is through their narratives in Skyfall, where we learn of a deeper dark ailment the world has – the disease of judgment and self-righteousness. The irony is incredibly strong in the story she is trying to tell and every facet of it is rife with an all too relatable hypocritical narrative - what will people say? Look but don’t touch, touch but don’t attach to, attach to but do not depend on, one by one, we witness all characters and the repeated chaos they meander their way through, because they do not conform to what society sees as correct – but who is society? Who dictates these morals and principles? Skyfall sheds light on the plight of marginalised populations across society, be it in Pakistan, India, Kashmir, or the beaming first world city of New York – no matter where they are, they are judged by a jury, a self-ordained structure of “God-like” figures who are placed on a mantle with limitless powers to crush anything that does not fall into their definition of pure. On one hand there is the clamouring cacophony for change, and on the other hand, the indifference of those who are in power: be it legal systems, nations, notions of morality or religion – both do not match and thus the world is still harrowingly hollow in its need to unite and act fairly, without discrimination. It is a reminder that a confused and dysfunctional world is in the making with varying degrees of wealth distribution and disillusioned notions of class systems. Khan provokes the reader to question what the ‘taboo’ of the red – light district really is and why these women are shamed by the elite and educated, when the real irony is, that it is through them that the sex industry is financially benefitted. Perhaps, the shame is actually their own and not of these helpless women.

The novel is divided into three parts: Nightfall, Day and Dawn – Khan uses powerful symbols of light and timing of day to represent the darkness, light, triumph and defeat in the main characters journeys and struggles. Khan’s style of acquainting the reader and empathizing with him or her is beyond measure: one feels an eruption of sorrow as we lose a character, one feels raging anger boil within us when there is injustice done to a character, equally so, one feels the love and warmth within various friendships and romantic relationships. Khan’s portrayal of female friendships throughout Skyfall, show a sense of women tribe comradery, thus break stereotypical notions that women from the red-light district and sex industry cannot be loyal. In fact, it is in these resounding relationships that the plot progresses, and the main characters’ challenges are nurtured and protected – hence providing them some solace while steering through their difficult journeys. It is in the warmth the mother nurturing and protecting her two daughters from a trade she was sold into, it is in the sister protecting her half sister from the dirty and destructive minds of the clergymen and those who in the name of religion condemn homosexuality, it is in the music instructor’s love, loyalty and confidante like demeanour towards girls in the damned neighbourhood that words of wisdom and advice on romantic relationships are passed on, it is in the church choir group and night school teachers running free of cost schools for children of the neighbourhood, in hopes that they will be something and transgress their stained origins. Khan plays on serendipitous friendships, acquaintances, and connections to challenge our notions of good and bad, and there is continued suspense through her writing in each new character’s motive, as the reader is heavily invested in air of distrust and sense of possessiveness and protection for all its characters – all unfortunately plagued ab initio with some misfortune through way of their sexual orientation, their religion, their lineage, or their country of origin. Khan uses the tool of weather, often used in literature to foreshadow events, there is rain, snow, heat, cold at varying intervals as and when the plot is revealed, playing in parallel with the main character’s emotions and inner conflicts.

In all of this, Khan’s choice of Rania as the main character is done on purpose, wise and strong as she is sensitive, is stifled by challenges and becomes the torchbearer of justice who stands for everyone – a surprising epitome of neutrality, given the instability, abuse and hardships she faced during her childhood and adolescent life. Khan introduces Rania’s personality in two interesting ways, her mother, Jahaan-e-Rumi, just upon Rania’s birth quickly scribbles her future belief and prayer for her first daughter, “she will be no stubborn, malevolent lunatic, but the fiercest girl in all the galaxies – a tempest but never unkind,”. Whilst the word “trouble-maker” is used by her father, Sherji, a man with double standards, despite his religious and moral beliefs has two malevolent side businesses: pimping and masterminding terrorist attacks, all the while being a violent bully at home, using his daughter and wife as sex workers for money that he will keep. Jahaan e Rumi, who becomes a pillar of support in her life, forewarns her and gives her encouragement that she is destined for much more than what she herself has gone through, “they will call you “the troublemaker”, but before you leave this world, you’ll cross the seven-mile bridge in Heera Mandi”. As a tour guide, she meets and connects romantically with Asher, a visiting independent filmmaker from India – despite a love so pure between them, due to the tussle between their countries and their religious differences, they would never be accepted in society. Their bond is a constant throughout the book, as is hers with the females in the neighbourhood, Roohi, Marzi, her sister Ujala and her friends in New York. Rania’s passion for singing is important as it not only reveals the plot, but also allows the author to incorporate Ghazals and allude to excerpts of Manto within the novel, at timely intervals, specifically when she wants to reveal the main character’s inner conflict and emotions. Her love for singing, although swayed and halted by external tragedies she finds herself emotionally coiled up in as an ode to the people she loves, battling with guilt, she still braves her way to contest in the local Mohalla singing competition and then internationally in New York. Rania’s character is constantly giving up her dream to fight for the people around her, be it against Sherji, her father for what he does with women, in his family and outside, the sexual abuse he perpetrates at a madrassa – a sacred and safe place of learning for children. Her fight against the educated elite in power for justice against her sister, who is beaten, raped, and hung in broad daylight for being a lesbian.

As a debutante novelist, Saba Karim Khan has an impeccable way with words, her ability to write so that the reader feels every jolt of every experience, be a cobbled alleyway in Lahore, the balmy mysticism of nights of romantic nights of the rooftop, the razor-sharp precision with which she evokes strong feelings, be it shock, awe, sorrow, or anger from the reader’s end – is completely unmatchable. Her ability to bravely touch upon a range of topics that hushed in public but revelled within inner circles, but with softness and a sense of story, piquing the reader’s interest towards her marvelous work of fiction. As a novel, Skyfall draws focus to larger disparities in society, though perhaps not directly connected or even unbridled by its narrative, all of us have experienced a sense of discrimination, whether its based on our experiences of patriarchy, country of origin, ethnicity, religion or our past. There is an indoctrinated sense of entitlement, better than thou and a blaring sense of judgment in the dogma of everyday life. The author bravely speaks about social issues in a thought-provoking manner but interesting enough to create a plot which is hard to put down. The characters within their journeys are all stereotypes and archetypes for various events and represent either the role of an oppressor or an ‘oppressed’. The book sheds light and draws parallels with events ongoing simultaneously in various parts of the world: the effects of a strong borderline fascist president and republican government in the United States, a cruel disconnection from the world in lockdown Indian Kashmir, the extremist religious group crackdowns in India against Muslims, and in Pakistan against Christians, cult and forceful missionary groups seeking vulnerable people to join their mission to bring purity in the United States and in Pakistan through cleansing of homosexuality, as if it is a thing that can be washed off, and not an identity. All characters reveal atrocity in their part of the world – allowing the reader to realise that there is injustice everywhere, regardless of how supposedly ‘civilised’ one part of the world is compared to another.

The book battles with characters seeking the truth, achieving justice in an unfair, patriarchal, and hypocritical world, and being defeated and vilified for just being themselves, free of judgment, and societal constraints. As I was almost at the end of the last few chapters of Skyfall, I drove down for a break from this review to a well-known juice franchise in Karachi, I pulled down my window and before I managed to speak, a car overtook me with a man who said “Mujhe aapka Fit For A King juice chahiye”, translation, “I would like your juice variety named Fit For A King.” I chuckled, as I thought of the new friends I had made in the female characters in Skyfall, those I longed to go home to. Characters if were still alive and together, would in some fictional land laugh and share their secrets over a “fit for a queen” chai and thus I decided to do the same in ode to them. Lots can change and we hope novels like Saba Karim Khan’s help in doing so in an interesting and light manner. Hope and justice to let every individual live a free life is something we can never stop fighting for, like Rania, we too, each denizen of Pakistan and the world, must embody the same spirit and sense of duty – hopefully, one day, creating a fairer world.

The writer is a lawyer and independent grant writing consultant. She also works in curatorial capacity for public museums and galleries.

It is exactly this haunting hypocrisy that Saba Karim Khan brilliantly identifies and beautifully pens in her debut novel, Skyfall. Khan does not have an easy task at hand, she plays with a plot and in it, themes and characters that are destined against all odds to fail - to fail at existing, to fail at living and even more so to fail at achieving justice of any kind.

It is as if she already knows this disconnected dilemma and thus, writes her prose ever so vividly, descriptively detailed, and poignantly versed, immediately immersing the reader into the chilling world of the unseen, unknown and inexperienced. The minute one picks this book, they are invited into the alleyways, quaint streets, pan shops, even the potholes, distinct aroma, distant music, and dance – they become part of the taboo, part of the secret, part of a select few the story chooses to confide in.

The hushed business of Heera Mandi, Lahore’s red-light district is broken down, and the reader becomes privy to it all, through its characters and the intimate, secret diary writing style that Khan crafts throughout the novel.

Skyfall reminds me of a novel I read years ago, called Shame by Salman Rushdie which plays with themes of shame, the sobriquet of its passive heroine who absorbs the shame around her, much like Khan’s main character, Rania. Both Rushdie’s ‘Shame’ and Khan’s ‘Skyfall’, speak not only of an individual’s shame but also society which gives shame an undue important and central place in their lives. Both novels also explore the interplay of disparate societies and the great chasms they present: the powerful and moneyed versus the poor and powerless, the educated and elite versus the so called uneducated and unenlightened and the question of mortality – right versus wrong. A particular verse from Rushdie’s Shame resonated with me after I finished Khan’s Skyfall: “Shame is like everything else; live with it long enough and it becomes part of the furniture. Between shame and shamelessness lies the axis upon which we turn; meteorological conditions at both these poles are of the most extreme, ferocious type. Shamelessness, shame; the roots of violence.”

Rushdie and Khan both through their novels intrinsically propel a reader to question how arbitrary shame is, by openly questioning and exploring what shame really is and how massive the impact of its pretence can be if not dealt with. How on one hand when one lives with it, one can get complacent to act against it, but on the other hand, when one does act against and achieves justice for a larger majority, it can be liberating – the choice is but ours.

Khan’s Skyfall is a tale of painful dichotomy, a world with a clear good and evil, but in a typecast setting, where we know which will reign and win – it is always those with the money, power and connections that do – not the faceless, shunned population she chooses as her characters. Khan posits the latter as the real heroes of our world, and it is through their narratives in Skyfall, where we learn of a deeper dark ailment the world has – the disease of judgment and self-righteousness. The irony is incredibly strong in the story she is trying to tell and every facet of it is rife with an all too relatable hypocritical narrative - what will people say? Look but don’t touch, touch but don’t attach to, attach to but do not depend on, one by one, we witness all characters and the repeated chaos they meander their way through, because they do not conform to what society sees as correct – but who is society? Who dictates these morals and principles? Skyfall sheds light on the plight of marginalised populations across society, be it in Pakistan, India, Kashmir, or the beaming first world city of New York – no matter where they are, they are judged by a jury, a self-ordained structure of “God-like” figures who are placed on a mantle with limitless powers to crush anything that does not fall into their definition of pure. On one hand there is the clamouring cacophony for change, and on the other hand, the indifference of those who are in power: be it legal systems, nations, notions of morality or religion – both do not match and thus the world is still harrowingly hollow in its need to unite and act fairly, without discrimination. It is a reminder that a confused and dysfunctional world is in the making with varying degrees of wealth distribution and disillusioned notions of class systems. Khan provokes the reader to question what the ‘taboo’ of the red – light district really is and why these women are shamed by the elite and educated, when the real irony is, that it is through them that the sex industry is financially benefitted. Perhaps, the shame is actually their own and not of these helpless women.

Khan’s Skyfall is a tale of painful dichotomy, a world with a clear good and evil, but in a typecast setting, where we know which will reign and win

The novel is divided into three parts: Nightfall, Day and Dawn – Khan uses powerful symbols of light and timing of day to represent the darkness, light, triumph and defeat in the main characters journeys and struggles. Khan’s style of acquainting the reader and empathizing with him or her is beyond measure: one feels an eruption of sorrow as we lose a character, one feels raging anger boil within us when there is injustice done to a character, equally so, one feels the love and warmth within various friendships and romantic relationships. Khan’s portrayal of female friendships throughout Skyfall, show a sense of women tribe comradery, thus break stereotypical notions that women from the red-light district and sex industry cannot be loyal. In fact, it is in these resounding relationships that the plot progresses, and the main characters’ challenges are nurtured and protected – hence providing them some solace while steering through their difficult journeys. It is in the warmth the mother nurturing and protecting her two daughters from a trade she was sold into, it is in the sister protecting her half sister from the dirty and destructive minds of the clergymen and those who in the name of religion condemn homosexuality, it is in the music instructor’s love, loyalty and confidante like demeanour towards girls in the damned neighbourhood that words of wisdom and advice on romantic relationships are passed on, it is in the church choir group and night school teachers running free of cost schools for children of the neighbourhood, in hopes that they will be something and transgress their stained origins. Khan plays on serendipitous friendships, acquaintances, and connections to challenge our notions of good and bad, and there is continued suspense through her writing in each new character’s motive, as the reader is heavily invested in air of distrust and sense of possessiveness and protection for all its characters – all unfortunately plagued ab initio with some misfortune through way of their sexual orientation, their religion, their lineage, or their country of origin. Khan uses the tool of weather, often used in literature to foreshadow events, there is rain, snow, heat, cold at varying intervals as and when the plot is revealed, playing in parallel with the main character’s emotions and inner conflicts.

In all of this, Khan’s choice of Rania as the main character is done on purpose, wise and strong as she is sensitive, is stifled by challenges and becomes the torchbearer of justice who stands for everyone – a surprising epitome of neutrality, given the instability, abuse and hardships she faced during her childhood and adolescent life. Khan introduces Rania’s personality in two interesting ways, her mother, Jahaan-e-Rumi, just upon Rania’s birth quickly scribbles her future belief and prayer for her first daughter, “she will be no stubborn, malevolent lunatic, but the fiercest girl in all the galaxies – a tempest but never unkind,”. Whilst the word “trouble-maker” is used by her father, Sherji, a man with double standards, despite his religious and moral beliefs has two malevolent side businesses: pimping and masterminding terrorist attacks, all the while being a violent bully at home, using his daughter and wife as sex workers for money that he will keep. Jahaan e Rumi, who becomes a pillar of support in her life, forewarns her and gives her encouragement that she is destined for much more than what she herself has gone through, “they will call you “the troublemaker”, but before you leave this world, you’ll cross the seven-mile bridge in Heera Mandi”. As a tour guide, she meets and connects romantically with Asher, a visiting independent filmmaker from India – despite a love so pure between them, due to the tussle between their countries and their religious differences, they would never be accepted in society. Their bond is a constant throughout the book, as is hers with the females in the neighbourhood, Roohi, Marzi, her sister Ujala and her friends in New York. Rania’s passion for singing is important as it not only reveals the plot, but also allows the author to incorporate Ghazals and allude to excerpts of Manto within the novel, at timely intervals, specifically when she wants to reveal the main character’s inner conflict and emotions. Her love for singing, although swayed and halted by external tragedies she finds herself emotionally coiled up in as an ode to the people she loves, battling with guilt, she still braves her way to contest in the local Mohalla singing competition and then internationally in New York. Rania’s character is constantly giving up her dream to fight for the people around her, be it against Sherji, her father for what he does with women, in his family and outside, the sexual abuse he perpetrates at a madrassa – a sacred and safe place of learning for children. Her fight against the educated elite in power for justice against her sister, who is beaten, raped, and hung in broad daylight for being a lesbian.

As a debutante novelist, Saba Karim Khan has an impeccable way with words, her ability to write so that the reader feels every jolt of every experience

As a debutante novelist, Saba Karim Khan has an impeccable way with words, her ability to write so that the reader feels every jolt of every experience, be a cobbled alleyway in Lahore, the balmy mysticism of nights of romantic nights of the rooftop, the razor-sharp precision with which she evokes strong feelings, be it shock, awe, sorrow, or anger from the reader’s end – is completely unmatchable. Her ability to bravely touch upon a range of topics that hushed in public but revelled within inner circles, but with softness and a sense of story, piquing the reader’s interest towards her marvelous work of fiction. As a novel, Skyfall draws focus to larger disparities in society, though perhaps not directly connected or even unbridled by its narrative, all of us have experienced a sense of discrimination, whether its based on our experiences of patriarchy, country of origin, ethnicity, religion or our past. There is an indoctrinated sense of entitlement, better than thou and a blaring sense of judgment in the dogma of everyday life. The author bravely speaks about social issues in a thought-provoking manner but interesting enough to create a plot which is hard to put down. The characters within their journeys are all stereotypes and archetypes for various events and represent either the role of an oppressor or an ‘oppressed’. The book sheds light and draws parallels with events ongoing simultaneously in various parts of the world: the effects of a strong borderline fascist president and republican government in the United States, a cruel disconnection from the world in lockdown Indian Kashmir, the extremist religious group crackdowns in India against Muslims, and in Pakistan against Christians, cult and forceful missionary groups seeking vulnerable people to join their mission to bring purity in the United States and in Pakistan through cleansing of homosexuality, as if it is a thing that can be washed off, and not an identity. All characters reveal atrocity in their part of the world – allowing the reader to realise that there is injustice everywhere, regardless of how supposedly ‘civilised’ one part of the world is compared to another.

The book battles with characters seeking the truth, achieving justice in an unfair, patriarchal, and hypocritical world, and being defeated and vilified for just being themselves, free of judgment, and societal constraints. As I was almost at the end of the last few chapters of Skyfall, I drove down for a break from this review to a well-known juice franchise in Karachi, I pulled down my window and before I managed to speak, a car overtook me with a man who said “Mujhe aapka Fit For A King juice chahiye”, translation, “I would like your juice variety named Fit For A King.” I chuckled, as I thought of the new friends I had made in the female characters in Skyfall, those I longed to go home to. Characters if were still alive and together, would in some fictional land laugh and share their secrets over a “fit for a queen” chai and thus I decided to do the same in ode to them. Lots can change and we hope novels like Saba Karim Khan’s help in doing so in an interesting and light manner. Hope and justice to let every individual live a free life is something we can never stop fighting for, like Rania, we too, each denizen of Pakistan and the world, must embody the same spirit and sense of duty – hopefully, one day, creating a fairer world.

The writer is a lawyer and independent grant writing consultant. She also works in curatorial capacity for public museums and galleries.