A whiff of scent, a familiar voice or a long-forgotten tune triggers and unleashes a torrent of memories. This essay is about North Wazirstan, the remote mountainous region of Pakistan that abuts the Durand Line. It is also about a memorable song.

The year was 1956.

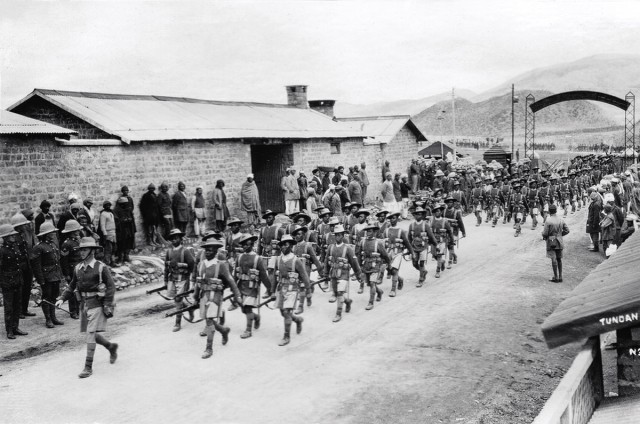

Wazirstan has been the restless and turbulent western frontier of British India for centuries. Here the British came face-to-face with an equally resolute and determined enemy and the face-off gave birth to many legends and quite a few myths. After the creation of Pakistan in 1947, nothing much changed except that the area was now nominally under the control of Pakistan instead of British India.

During the decade-old war against the Soviets in Afghanistan (1879-89), Wazirstan and some of the tribal areas adjoining the Durand Line became the frontline combat zones for the Mujahideen. After the defeat of the Soviets in 1989, the areas did not settle down but instead became first the proving ground for warring Afghan factions during the Afghan civil war and later, during the Taliban insurgency, a haven for the Taliban. During the rule of the successive US-installed Afghan governments, the Taliban used Wazirstan as a staging area for attacks on the Coalition forces as well as against the Afghan government. North Wazirstan earned the moniker ‘Badlands.’

Pakistan invested heavily in the uplifting of Wazirstan by building schools, hospitals and establishing industries. In 1977 Pakistan established a cadet college at Razmak. This secondary high school was to prepare students for the armed forces as well as for other professions. But that did not bring stability to the region either.

The rock bottom was reached during the decades of 1990 and 2000 when the Taliban declared the area an independent Islamic Emirate. A massive operation by Pakistani army in 2005 brought the area under Pakistani control.

The British had created the ambiguity of semi-autonomous tribal lands between British India and Afghanistan. In 2018 Pakistan went ahead and removed the ambiguity by incorporating tribal regions into Pakistan. Even though the writ of Islamabad now extended up to the Durand Line, split loyalties are still there.

Let us now return to 1956, the time of this essay.

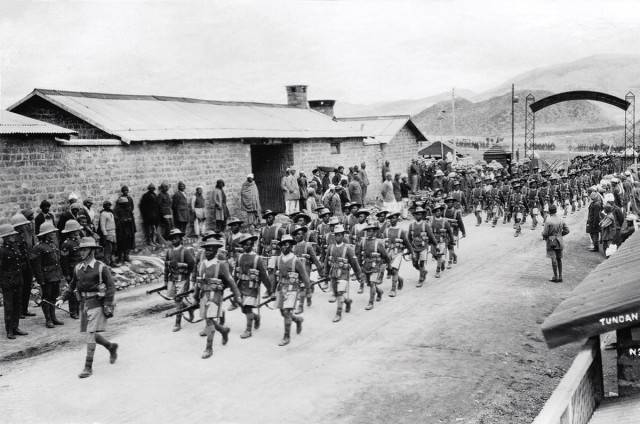

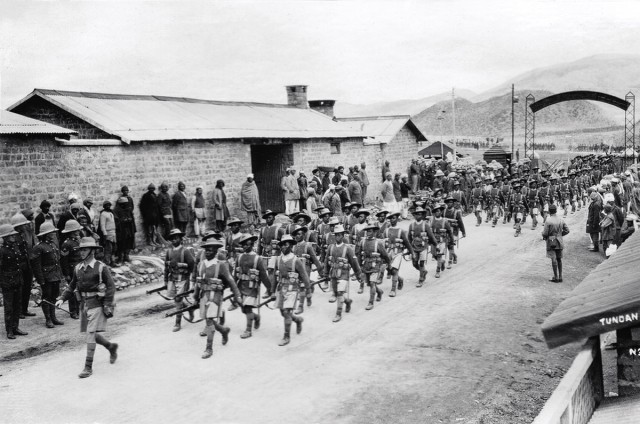

At the time Pakistan administered the area through civil service officers called political agents. Instead of regular Pakistan army units, the paramilitary Frontier Constabulary maintained law and order, and guarded the frontier between Afghanistan and Pakistan. The soldiers were recruited from among the tribes in order to give them a sense of ownership. The militia were known by local names such as Chital Scouts, Khyber Rifles etc.

Political agents administered the areas under their command with the help of tribal elders. Large subsidies to the tribes were used to keep them in line. Still sometimes there were kidnappings of government officials for ransom. Pressure by the administration and the tribal chiefs and some money usually had the desired effect and the captive was released.

I used to spend summer vacations in Miram Shah, the headquarter of North Wazirstan, with my elder brother Zulfiqar, who was posted there in the mid 1950s as a civil engineer. Travel was easy and safe in those days. From Peshawar, I would travel 200 km south to Bannu by bus and then take another bus for the 70 km ride west to Miram Shah. I could walk around the town without any hindrance. Miram Shah was relatively tranquil and peaceful.

It was during one of my summer-long visits to Miram Shah that my brother planned to go on tour to inspect a few under-construction projects in Razmak. While Miram Shah was relatively safe for government officials, any excursions into the countryside were fraught with danger.

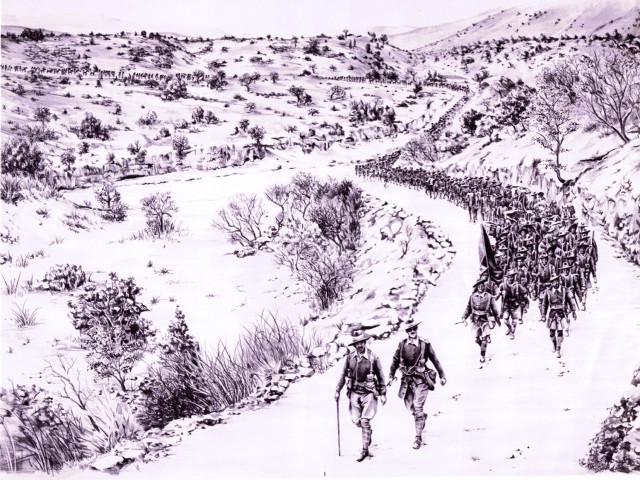

The British has devised a way where government officials could travel under the protection of armed guards recruited from the tribes and clans that were dominant in the territory the officers visited. The idea was that having local tribesman accompanying the officers would restrain the tribe from attacking the convoy. In case of a violation, the entire tribe or clan would receive collective punishment.

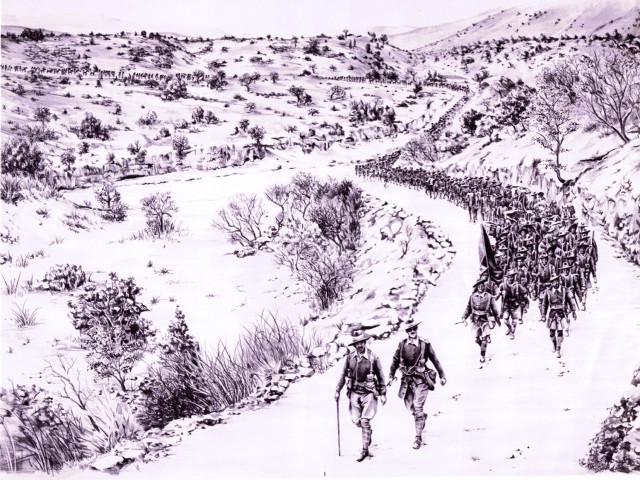

On a sunny summer day, we traveled 80 km southwest to Razmak in a specially hired bus. The guards called ‘badragas’ sat on the roof of the bus with loaded guns and the rest of us sat inside. It was a pleasant slow-paced journey through beautiful mountain vistas. It was a slow tread because of the poor condition of the road. As we started to climb higher, the air started to feel cool. It was not unlike the travel from Rawalpindi to Murree during summer months. As one ascends towards Murree, the suffocating hot air is gradually replaced with cooler and more pleasant mountain air.

Razmak was developed by the British as a charming small garrison town to keep an eye on the surrounding areas. The two-tier small town was called, in army jargon, the upper camp and the lower camp. Going through the town was as if one were walking in small-town Britannia, with small shops, churches, general stores and cafes. An exception was the presence of a small mosque and a Hindu temple. The town was called Chota Wilayat or Little England. And also, Chota London.

The town or camp was presided over by a commandant, generally a relatively low-ranking army officer. Before independence Captain Iskander Mirza was officer in charge of Razmak. Through intrigue and sheer force of his personality, he would later rise precipitously and become the president of Pakistan just before the army coup in 1958. General Ayub Khan, the incoming strongman, packed him off to Britain to live in exile, where he died.

In 1947, Pakistan withdrew its army from the tribal areas in a gesture of good will towards the tribes. The town was also abandoned. The tribesmen took advantage and hauled away anything and everything that was not nailed down or set in concrete. At the time of our visit in 1956, most of the buildings were still intact. However, it required a bit of imagination to understand how charming and beautiful the town had been. I saw two donkeys resting comfortably in the wood-paneled drawing room of the commandant’s house.

Our host, a local chieftain, lived in a large house that clung to the side of the mountain with a clear view of the now abandoned Chota Wilayat. He took considerable pleasure in pointing-out various spots in and around the town where he had taken pot shots at the British soldiers and officers – and he had killed quite a few!

That night after a sumptuous meal of freshly baked whole wheat tandoori bread, chicken curry, pulao and cooked vegetables, we stretched on comfortable beddings spread over charpais in the courtyard of the Malik’s home. After a while the conversation died down and we were all caught in the moment where we laid on our beds observing a fascinating world of stars in the dark sky.

In that quiet, I heard the undulating voice of Lata Mangeshkar riding the breeze from somewhere in the mountains. Since Razmak and surrounding mountains had no electricity at the time, it must have been a radio operated with a car battery.

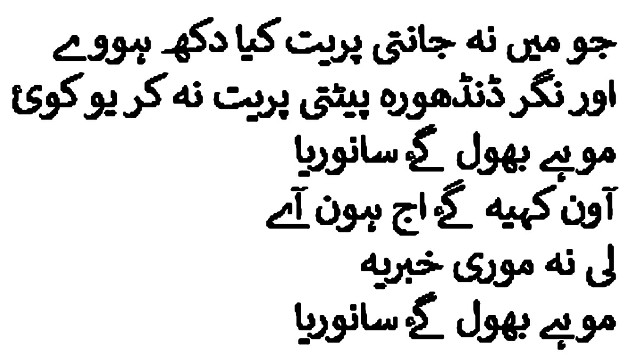

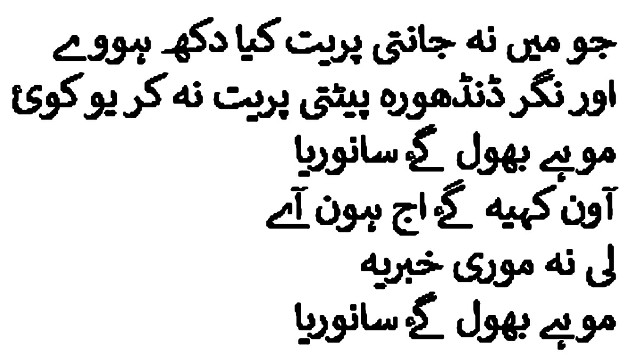

If I had only known the heartbreak of love,

I would have, like a town crier, cried out to people

Do not to fall in love.

My love forgot me

He said he would be back soon

But he never looked back

My love forgot me

That was 65 years ago. Still when I listen to that song, I drift off to the beautiful night in the mountains of North Wazirstan just above Chota London where Lata’s voice riding the gentle mountain breeze cast an ever-lasting spell.

Such is the enduring magic of music.

P.S.: Baiju Bawra was a super hit film of 1952. It was directed by Vijay Bhatt. The lyrics were written by Shakeel Badayuni and the music was composed by Naushad. All songs were set in various classis ragas. Moi Bhool Gai Sanwariya was set in Raga Bhairavi

Dr. Sayed Amjad Hussain holds Emeritus professorships in Humanities and cardiovascular surgery at the University of Toledo, USA. He is also an op-ed columnist for Toledo Blade and daily Aaj of Peshawar.

Contact: aghaji@bex.net

The year was 1956.

Wazirstan has been the restless and turbulent western frontier of British India for centuries. Here the British came face-to-face with an equally resolute and determined enemy and the face-off gave birth to many legends and quite a few myths. After the creation of Pakistan in 1947, nothing much changed except that the area was now nominally under the control of Pakistan instead of British India.

During the decade-old war against the Soviets in Afghanistan (1879-89), Wazirstan and some of the tribal areas adjoining the Durand Line became the frontline combat zones for the Mujahideen. After the defeat of the Soviets in 1989, the areas did not settle down but instead became first the proving ground for warring Afghan factions during the Afghan civil war and later, during the Taliban insurgency, a haven for the Taliban. During the rule of the successive US-installed Afghan governments, the Taliban used Wazirstan as a staging area for attacks on the Coalition forces as well as against the Afghan government. North Wazirstan earned the moniker ‘Badlands.’

Pakistan invested heavily in the uplifting of Wazirstan by building schools, hospitals and establishing industries. In 1977 Pakistan established a cadet college at Razmak. This secondary high school was to prepare students for the armed forces as well as for other professions. But that did not bring stability to the region either.

The rock bottom was reached during the decades of 1990 and 2000 when the Taliban declared the area an independent Islamic Emirate. A massive operation by Pakistani army in 2005 brought the area under Pakistani control.

The British had created the ambiguity of semi-autonomous tribal lands between British India and Afghanistan. In 2018 Pakistan went ahead and removed the ambiguity by incorporating tribal regions into Pakistan. Even though the writ of Islamabad now extended up to the Durand Line, split loyalties are still there.

Let us now return to 1956, the time of this essay.

At the time Pakistan administered the area through civil service officers called political agents. Instead of regular Pakistan army units, the paramilitary Frontier Constabulary maintained law and order, and guarded the frontier between Afghanistan and Pakistan. The soldiers were recruited from among the tribes in order to give them a sense of ownership. The militia were known by local names such as Chital Scouts, Khyber Rifles etc.

Political agents administered the areas under their command with the help of tribal elders. Large subsidies to the tribes were used to keep them in line. Still sometimes there were kidnappings of government officials for ransom. Pressure by the administration and the tribal chiefs and some money usually had the desired effect and the captive was released.

Our host, a local chieftain, lived in a large house that clung to the side of the mountain with a clear view of the now abandoned Chota Wilayat

I used to spend summer vacations in Miram Shah, the headquarter of North Wazirstan, with my elder brother Zulfiqar, who was posted there in the mid 1950s as a civil engineer. Travel was easy and safe in those days. From Peshawar, I would travel 200 km south to Bannu by bus and then take another bus for the 70 km ride west to Miram Shah. I could walk around the town without any hindrance. Miram Shah was relatively tranquil and peaceful.

It was during one of my summer-long visits to Miram Shah that my brother planned to go on tour to inspect a few under-construction projects in Razmak. While Miram Shah was relatively safe for government officials, any excursions into the countryside were fraught with danger.

The British has devised a way where government officials could travel under the protection of armed guards recruited from the tribes and clans that were dominant in the territory the officers visited. The idea was that having local tribesman accompanying the officers would restrain the tribe from attacking the convoy. In case of a violation, the entire tribe or clan would receive collective punishment.

On a sunny summer day, we traveled 80 km southwest to Razmak in a specially hired bus. The guards called ‘badragas’ sat on the roof of the bus with loaded guns and the rest of us sat inside. It was a pleasant slow-paced journey through beautiful mountain vistas. It was a slow tread because of the poor condition of the road. As we started to climb higher, the air started to feel cool. It was not unlike the travel from Rawalpindi to Murree during summer months. As one ascends towards Murree, the suffocating hot air is gradually replaced with cooler and more pleasant mountain air.

Razmak was developed by the British as a charming small garrison town to keep an eye on the surrounding areas. The two-tier small town was called, in army jargon, the upper camp and the lower camp. Going through the town was as if one were walking in small-town Britannia, with small shops, churches, general stores and cafes. An exception was the presence of a small mosque and a Hindu temple. The town was called Chota Wilayat or Little England. And also, Chota London.

The town or camp was presided over by a commandant, generally a relatively low-ranking army officer. Before independence Captain Iskander Mirza was officer in charge of Razmak. Through intrigue and sheer force of his personality, he would later rise precipitously and become the president of Pakistan just before the army coup in 1958. General Ayub Khan, the incoming strongman, packed him off to Britain to live in exile, where he died.

In 1947, Pakistan withdrew its army from the tribal areas in a gesture of good will towards the tribes. The town was also abandoned. The tribesmen took advantage and hauled away anything and everything that was not nailed down or set in concrete. At the time of our visit in 1956, most of the buildings were still intact. However, it required a bit of imagination to understand how charming and beautiful the town had been. I saw two donkeys resting comfortably in the wood-paneled drawing room of the commandant’s house.

Our host, a local chieftain, lived in a large house that clung to the side of the mountain with a clear view of the now abandoned Chota Wilayat. He took considerable pleasure in pointing-out various spots in and around the town where he had taken pot shots at the British soldiers and officers – and he had killed quite a few!

That night after a sumptuous meal of freshly baked whole wheat tandoori bread, chicken curry, pulao and cooked vegetables, we stretched on comfortable beddings spread over charpais in the courtyard of the Malik’s home. After a while the conversation died down and we were all caught in the moment where we laid on our beds observing a fascinating world of stars in the dark sky.

In that quiet, I heard the undulating voice of Lata Mangeshkar riding the breeze from somewhere in the mountains. Since Razmak and surrounding mountains had no electricity at the time, it must have been a radio operated with a car battery.

If I had only known the heartbreak of love,

I would have, like a town crier, cried out to people

Do not to fall in love.

My love forgot me

He said he would be back soon

But he never looked back

My love forgot me

That was 65 years ago. Still when I listen to that song, I drift off to the beautiful night in the mountains of North Wazirstan just above Chota London where Lata’s voice riding the gentle mountain breeze cast an ever-lasting spell.

Such is the enduring magic of music.

P.S.: Baiju Bawra was a super hit film of 1952. It was directed by Vijay Bhatt. The lyrics were written by Shakeel Badayuni and the music was composed by Naushad. All songs were set in various classis ragas. Moi Bhool Gai Sanwariya was set in Raga Bhairavi

Dr. Sayed Amjad Hussain holds Emeritus professorships in Humanities and cardiovascular surgery at the University of Toledo, USA. He is also an op-ed columnist for Toledo Blade and daily Aaj of Peshawar.

Contact: aghaji@bex.net