Right after the election, democracy had not yet started to make progress but the affluent class had started to make plans to make the popular forces fail and to malign them. An artificial atmosphere of fear and despair was created, investments were ceased, shares of companies were thrown into the stock market but there was no buyer for them, prices of articles were raised and people were made to believe that the entire responsibility of this economic crisis was upon the democratic forces. One was amazed that government institutions like the National Investment Trust (NIT) too were also part of this conspiracy. So it was estimated that due to the style of action of these institutions, the stock market faced a loss of Rs. 100 million in a week. This artificial crisis was a clear proof of the fact that political democracy without economic democracy is no more than a mental luxury.

It is said that Raja Ravana of Lanka had a thousand hands and when one of his hands got injured, he began to fight with the other hand. Similarly, the affluent classes, too, have a thousand hands. They do not admit defeat easily nor do they withdraw happily from their political and economic dominance. It is correct that the people clearly defeated them in the 1970 elections but wealth is not an intoxication which the acrimonies of elections can take off. The power of this class was not so dependent on the numbers of capitalist elements in the national and provincial assemblies as on the monopoly over the sources of wealth creation. This class controlled banks and insurance companies, factories and workshops. The entire business of import and export was in its hands. The stock market became brisk and slow at the gesture of the very same people. The rates in the markets rose and fell with their consent. They too reduced and raised the process of articles and fixed the demand and supply as well. In addition, they also had the cooperation of the capitalists of the United States, Britain, Germany and Japan, etc. In short, like the enchanted bird the life of our economic system was in the hands of this same wealthy class. It could throttle our economic life whenever it wanted. The need of the hour was to beware this unlimited power of the enemy.

The stamp of this economic power of the wealthy could also be found on our national laws and institutions of law and order. It seemed like the national laws treated everyone equally and the administration was totally unbiased but upon reflection, one found that all the laws formulated since the British period, the objective of the majority of them was to maintain the prevalent relations of power and to preserve the institutions of private property. The law and administration both arrayed against popular demands whether it be the clash of democracy and dictatorship, the conflict of capital and labour, the struggle for citizens’ rights or the demand for wage increases. Sometimes Section 144 was imposed to maintain peace, sometimes strikes were declared illegal under cover of basic industry, sometimes people were arrested without registering a case against them or presenting them in court for the security of Pakistan; though there was no such law to allow for those who raised the prices of basic necessities to be punished. No law was present according to which a case be registered upon non-provision of conveniences of medicine and treatment; or to investigate those who kept the nation ignorant; or according to which the hungry, homeless, unclothed and unemployed could move the chains of the court.

In short our economic and social life was at that moment held captive inside a triangle. One angle of this triangle represented the interest of the capitalist class and the second, law; and the third was the bureaucracy. All these three angles were related to each other as well as being helpers and supporters of each other. No problem of the people could be solved without breaking the power of this triangle nor the newborn plant of democracy could bear flowers and fruit.

The big question confronting the victors of the 1970 elections in Pakistan was how to break the power of this triangle of power. The challenge before the Awami League and Peoples Party was to act honestly upon the socialist principles of their manifestos while formulating a constitution because the people had sent these parties to the National Assembly on the belief that they would organize the social and economic life of the country according to socialist ideology; but the preparation of the constitution would take upto 4-6 months and then the promulgation of the constitution and the advent of the democratic government would also take some time. Meanwhile would the democratic-minded people sit on the fence and give the capitalists the opportunity to conspire to destroy the economic system of the country or spread fear and despair about the future among the people?

Looked at from this aspect, Pakistan was passing through an extremely delicate period at that time. It was the responsibility of all left-wing parties to reflect seriously upon the new dangers, not consider the enemy as insignificant; in fact to organize the people for a new struggle. The struggle against the capitalist system was the next step of the struggle for political democracy and the logical act of moving further. The people had thrown down the enemy from the political field, but the need was to defeat it in the economic field too, on the condition that the left-wing parties united to lead them.

In the 1970 elections, the Pakistani people did indeed declare their disgust and disloyalty with the old possessors of power and politics, but that did not mean that the poison of prejudice, shortsightedness, emotionalism, personality-worship and unconscious following that had been mixed within the hearts and minds of the people for 23 years prior, had ceased in its effects too in just a single day and night. The antidote to this poison would indeed be furnished when some new political leadership would take the training of the peoples’ minds on a new basis upon itself, compile the importance of basic public issues for them and according to this importance fix some right manner of thinking and effective manner of action for them.

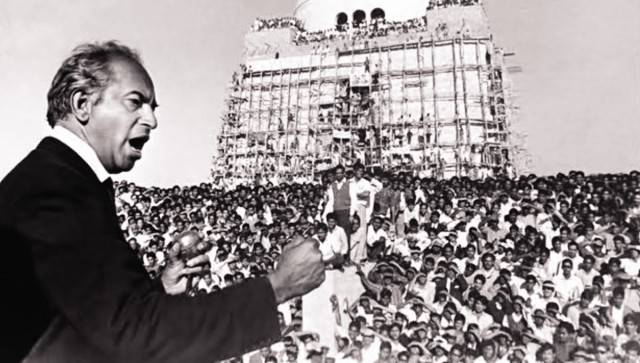

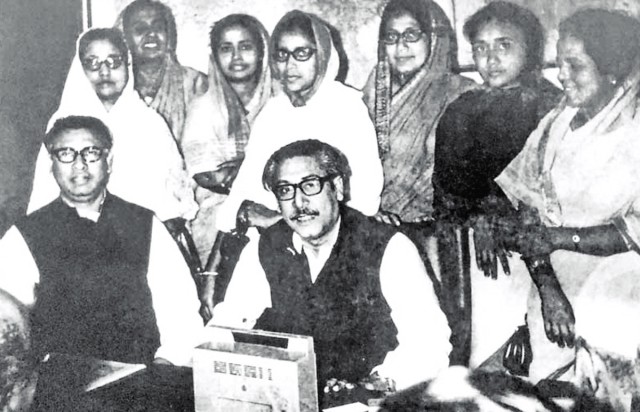

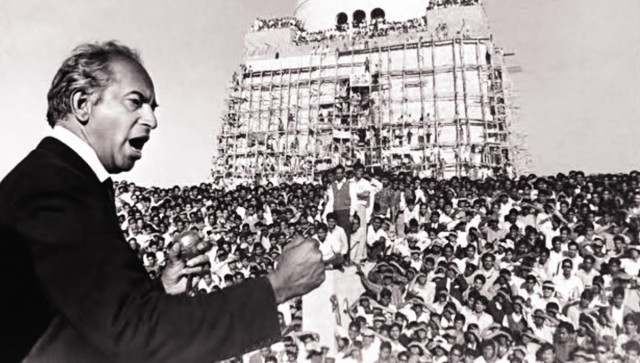

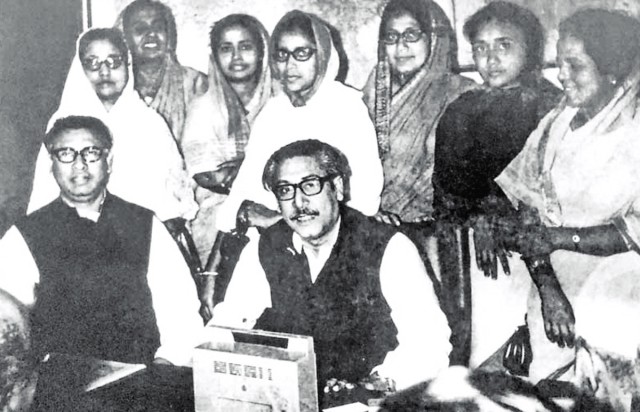

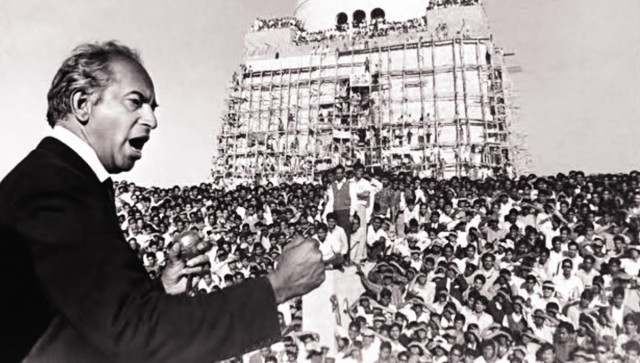

Alas, all of this came to naught as the elected Assembly initially did not meet: for the dictator Yahya Khan and the Pakistan Peoples Party did not want the majority party from East Pakistan forming a government. This caused great unrest in East Pakistan which soon escalated into the call for independence on March 26, 1971 and ultimately led to a war of independence with East Pakistan becoming the independent state of Bangladesh. The Assembly session was eventually held when Khan resigned four days after Pakistan surrendered in Bangladesh and Bhutto took over. Bhutto became the Prime Minister of Pakistan in 1973, after the post was recreated by the new Constitution.

The new leadership which emerged in Pakistan at the head of popular movements after the 1970 elections probably did not have the self-confidence to view every matter as one of providing leadership rather than following the people; and to convey directions to the people rather than inscribing a stamp of confirmation upon their ignorance. But it must have felt that it no longer had to confront the stage of elections – and instead now it faced those responsibilities which the people had granted to them as a result of these elections. These responsibilities related to constitution-making within the National Assembly too as well as the provision of bread, clothing and shelter to the people without.

The lesson from the 1970 elections that eventually broke Pakistan a year later and their aftermath was that the popularity which is attained by riding upon the shoulders of the people is indeed temporary. These events proved and continue to prove in Naya Pakistan 50 years on that permanent and durable leadership is the one which remains steadfast on the righteous path of ideas and action for the completion of the true interests of the people.

One of our finest humorous poets Syed Muhammad Jafri succinctly captured the moment as it transpired:

‘Ik doosre ko kar rahe hein zaleel

Aur aabroo bachane ki milti nahin sabeel

Roshan hui hai aatish-e-Namrood be-daleel

Milte nahin hein aag mein girne ko phir Khaleel

Phir sheikh-o-rind-o-rahroo-e-shab aik ho gaye

Achha nahin hai jin ka nasab aik ho gaye’

(Men are debasing one another

There is no means to save one’s honour

Without argument, brightens Nimrod’s pyre

No Abrahams are now found to fall into the fire

United then were the shaikh, the drunkard and the traveler of the night

United were those whose lineage was not so right)

Ilekshan Ke Baad (After the Election, 1971)

All the translations from the Urdu are by the author. Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader, currently based in Lahore, where he is also the president of the Progressive Writers Association. He can be reached at razanaeem@hotmail.com

It is said that Raja Ravana of Lanka had a thousand hands and when one of his hands got injured, he began to fight with the other hand. Similarly, the affluent classes, too, have a thousand hands. They do not admit defeat easily nor do they withdraw happily from their political and economic dominance. It is correct that the people clearly defeated them in the 1970 elections but wealth is not an intoxication which the acrimonies of elections can take off. The power of this class was not so dependent on the numbers of capitalist elements in the national and provincial assemblies as on the monopoly over the sources of wealth creation. This class controlled banks and insurance companies, factories and workshops. The entire business of import and export was in its hands. The stock market became brisk and slow at the gesture of the very same people. The rates in the markets rose and fell with their consent. They too reduced and raised the process of articles and fixed the demand and supply as well. In addition, they also had the cooperation of the capitalists of the United States, Britain, Germany and Japan, etc. In short, like the enchanted bird the life of our economic system was in the hands of this same wealthy class. It could throttle our economic life whenever it wanted. The need of the hour was to beware this unlimited power of the enemy.

The stamp of this economic power of the wealthy could also be found on our national laws and institutions of law and order. It seemed like the national laws treated everyone equally and the administration was totally unbiased but upon reflection, one found that all the laws formulated since the British period, the objective of the majority of them was to maintain the prevalent relations of power and to preserve the institutions of private property. The law and administration both arrayed against popular demands whether it be the clash of democracy and dictatorship, the conflict of capital and labour, the struggle for citizens’ rights or the demand for wage increases. Sometimes Section 144 was imposed to maintain peace, sometimes strikes were declared illegal under cover of basic industry, sometimes people were arrested without registering a case against them or presenting them in court for the security of Pakistan; though there was no such law to allow for those who raised the prices of basic necessities to be punished. No law was present according to which a case be registered upon non-provision of conveniences of medicine and treatment; or to investigate those who kept the nation ignorant; or according to which the hungry, homeless, unclothed and unemployed could move the chains of the court.

In short our economic and social life was at that moment held captive inside a triangle. One angle of this triangle represented the interest of the capitalist class and the second, law; and the third was the bureaucracy. All these three angles were related to each other as well as being helpers and supporters of each other. No problem of the people could be solved without breaking the power of this triangle nor the newborn plant of democracy could bear flowers and fruit.

The new leadership which emerged in Pakistan at the head of popular movements after the 1970 elections probably did not have the self-confidence to view every matter as one of providing leadership rather than following the people

The big question confronting the victors of the 1970 elections in Pakistan was how to break the power of this triangle of power. The challenge before the Awami League and Peoples Party was to act honestly upon the socialist principles of their manifestos while formulating a constitution because the people had sent these parties to the National Assembly on the belief that they would organize the social and economic life of the country according to socialist ideology; but the preparation of the constitution would take upto 4-6 months and then the promulgation of the constitution and the advent of the democratic government would also take some time. Meanwhile would the democratic-minded people sit on the fence and give the capitalists the opportunity to conspire to destroy the economic system of the country or spread fear and despair about the future among the people?

Looked at from this aspect, Pakistan was passing through an extremely delicate period at that time. It was the responsibility of all left-wing parties to reflect seriously upon the new dangers, not consider the enemy as insignificant; in fact to organize the people for a new struggle. The struggle against the capitalist system was the next step of the struggle for political democracy and the logical act of moving further. The people had thrown down the enemy from the political field, but the need was to defeat it in the economic field too, on the condition that the left-wing parties united to lead them.

In the 1970 elections, the Pakistani people did indeed declare their disgust and disloyalty with the old possessors of power and politics, but that did not mean that the poison of prejudice, shortsightedness, emotionalism, personality-worship and unconscious following that had been mixed within the hearts and minds of the people for 23 years prior, had ceased in its effects too in just a single day and night. The antidote to this poison would indeed be furnished when some new political leadership would take the training of the peoples’ minds on a new basis upon itself, compile the importance of basic public issues for them and according to this importance fix some right manner of thinking and effective manner of action for them.

Alas, all of this came to naught as the elected Assembly initially did not meet: for the dictator Yahya Khan and the Pakistan Peoples Party did not want the majority party from East Pakistan forming a government. This caused great unrest in East Pakistan which soon escalated into the call for independence on March 26, 1971 and ultimately led to a war of independence with East Pakistan becoming the independent state of Bangladesh. The Assembly session was eventually held when Khan resigned four days after Pakistan surrendered in Bangladesh and Bhutto took over. Bhutto became the Prime Minister of Pakistan in 1973, after the post was recreated by the new Constitution.

The big question confronting the victors of the 1970 elections in Pakistan was how to break this triangle

of power

The new leadership which emerged in Pakistan at the head of popular movements after the 1970 elections probably did not have the self-confidence to view every matter as one of providing leadership rather than following the people; and to convey directions to the people rather than inscribing a stamp of confirmation upon their ignorance. But it must have felt that it no longer had to confront the stage of elections – and instead now it faced those responsibilities which the people had granted to them as a result of these elections. These responsibilities related to constitution-making within the National Assembly too as well as the provision of bread, clothing and shelter to the people without.

The lesson from the 1970 elections that eventually broke Pakistan a year later and their aftermath was that the popularity which is attained by riding upon the shoulders of the people is indeed temporary. These events proved and continue to prove in Naya Pakistan 50 years on that permanent and durable leadership is the one which remains steadfast on the righteous path of ideas and action for the completion of the true interests of the people.

One of our finest humorous poets Syed Muhammad Jafri succinctly captured the moment as it transpired:

‘Ik doosre ko kar rahe hein zaleel

Aur aabroo bachane ki milti nahin sabeel

Roshan hui hai aatish-e-Namrood be-daleel

Milte nahin hein aag mein girne ko phir Khaleel

Phir sheikh-o-rind-o-rahroo-e-shab aik ho gaye

Achha nahin hai jin ka nasab aik ho gaye’

(Men are debasing one another

There is no means to save one’s honour

Without argument, brightens Nimrod’s pyre

No Abrahams are now found to fall into the fire

United then were the shaikh, the drunkard and the traveler of the night

United were those whose lineage was not so right)

Ilekshan Ke Baad (After the Election, 1971)

All the translations from the Urdu are by the author. Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader, currently based in Lahore, where he is also the president of the Progressive Writers Association. He can be reached at razanaeem@hotmail.com